Major Characteristics of Dickinson`s Poetry

advertisement

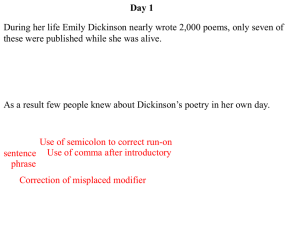

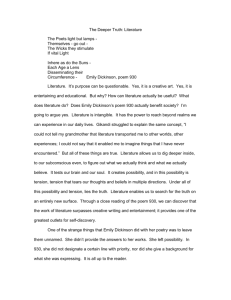

Major Characteristics of Dickinson's Poetry Take notes from your classmates in the spaces below. You should have one or two general points and one specific reference to the poem shown here “I’ll tell you how the Sun rose.” Theme and Tone I’ll tell you how the Sun rose – A Ribbon at a time – The steeples swam in Amethyst The news, like Squirrels, ran – The Hills untied their Bonnets – The Bobolinks – begun – Then I said softly to myself – “That must have been the Sun”! But how he set – I know not – There seemed a purple stile That little Yellow boys and girls Were climbing all the while – Till when they reached the other side – A Dominie in Gray – Put gently up the evening Bars – And led the flock away – Meter and Rhyme Diction Form and Style Punctuation and Syntax Form and Style Dickinson’s poems are lyrics, generally defined as short poems with a single speaker (not necessarily the poet) who expresses thought and feeling. As in most lyric poetry, the speaker in Dickinson's poems is often identified in the first person, "I." Dickinson reminded a reader that the “I” in her poetry does not necessarily speak for the poet herself: “When I state myself, as the Representative of the Verse – it does not mean – me – but a supposed person” (L268). In this poem the "I" addresses the reader as "you." Like just about all of Dickinson’s poems, this poem has no title. Dickinson titled fewer than 10 of her almost 1800 poems. Her poems are now generally known by their first lines or by the numbers assigned to them by posthumous editors. For some of Dickinson's poems, more than one manuscript version exists. "I'll tell you how the Sun rose" exists in two manuscripts. In one, the poem is broken into four stanzas of four lines each; in the other, as you see here, there are no stanza breaks. Meter and Rhyme The meter, or the rhythm of the poem, is usually determined not just by the number of syllables in a line but by how the syllables are accented. Dickinson’s verse is often associated with common meter, which is defined by alternating lines of eight syllables and six syllables (8686). In common meter, the syllables usually alternate between unstressed (indicated by a ˘ over the syllable) and stressed (′). This pattern--one of several types of metrical "feet"--is known as an "iamb." Common meter is often used in sung music, especially hymns (think "Amazing Grace"). Below is an example of common meter from "I'll tell you how the Sun rose." Emily Dickinson did experiment with a variety of metrical and stanzaic forms, including short meter (6686) and the ballad stanza, which depends more on beats per line (usually 4 alternating with 3) than on exact syllable counts. Even in common meter, she was not always strict about the number of syllables per line, as the first line in “I’ll tell you how the Sun rose” demonstrates. As with meter, Dickinson’s employment of rhyme is experimental and often not exact. Rhyme that is not perfect is called “slant rhyme” or “approximate rhyme.” Slant rhyme, or no rhyme at all, is quite common in modern poetry, but it was less often used in poetry written by Dickinson’s contemporaries. In this poem, for example, we would expect "time" to rhyme with "ran." Theme and Tone Like most writers, Emily Dickinson wrote about what she knew and about what intrigued her. A keen observer, she used images from nature, religion, law, music, commerce, medicine, fashion, and domestic activities to probe universal themes: the wonders of nature, the identity of the self, death and immortality, and love. In this poem, she probes nature's mysteries through the lens of the rising and setting sun. Dickinson writes about her subjects with humor as well as pathos. Remembering that she had a strong wit often helps to discern the tone behind her words. This poem contains whimsical images, but also includes profound reflections on human perception and the limits of language. A Dickinson poem is often not the expression of any single idea but the movement between ideas or images. It offers that rare privilege of watching a mind at work. The question of how we know anything comes alive as we read Dickinson. Punctuation and Syntax Dickinson most often punctuated her poems with dashes, rather than the more expected array of periods, commas, and other punctuation marks. She also capitalized interior words, not just words at the beginning of a line. Her reasons are not entirely clear. Both the use of dashes and the use of capitals to stress and personify common nouns were condoned by the grammar text (William Harvey Wells' Grammar of the English Language) that Mount Holyoke Female Seminary adopted and that Dickinson undoubtedly studied to prepare herself for entrance to that school. In addition, the dash was liberally used by many writers, as correspondence from the mid-nineteenth-century demonstrates. While Dickinson was far from the only person to employ it, she may have been the only poet to depend upon it. While Dickinson's dashes often stand in for more varied punctuation, at other times they serve as bridges between sections of the poem—bridges that are not otherwise readily apparent. Dickinson may also have intended for the dashes to indicate pauses when reading the poem aloud. Diction Dickinson’s editing process often focused on word choice rather than on experiments with form or structure. She recorded variant wordings with a “+” footnote on her manuscript. Sometimes words with radically different meanings are suggested as possible alternatives. Dickinson changed no words between the two versions of "I'll tell you how the Sun rose." But her use of words such as “boblink” ( a blackbird with a reckless song), a “stile” (set of stone steps) and “dominie” (a preacher or schoolmaster) are good examples of the attention she paid to both sound and connotation in her unusual word choice. Because Dickinson did not publish her poems, she did not have to choose among the different versions of her poems, or among her variant words, to create a "finished" poem. This lack of final authorial choices posed a major challenge to Dickinson’s subsequent editors. Emily Dickinson once wrote, “ . . . for several years, my Lexicon was my only companion” (L261). She had an exceptional command of the English language. Look up words that are unfamiliar, or that she uses in unfamiliar ways.