Theater of the Absurd Source 1: Jacobus, Lee A. The Bedford

advertisement

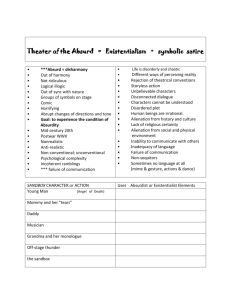

Theater of the Absurd Source 1: Jacobus, Lee A. The Bedford Introduction to Drama, 5th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2005. Print. A type of twentieth-century drama presenting the human condition as meaningless, absurd, and illogical. Source 2: Murfin, Ross and Supryia M. Ray. The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms. 2nd ed. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003. 479. Print. A phrase referring to twentieth-century works that depict the absurdity of the modern human condition, often with implicit reference to humanity's loss or lack of religious, philosophical, or cultural roots. Such works depict the individual as essentially isolated and alone, even when surrounded by other people and things. Although drama has been the medium of choice for Absurdist writers, the term may be applied to any work of literature that stresses an existential outlook, that is, one depicting the lonely, confused, and often anguished individual in an utterly bewildering universe. Because writers associated with this movement believe that the only way to represent the absurdity of the modern condition is to write in an absurd manner, the literature of the Absurd is as bizarre in style as it is in subject matter. Conventions governing everything from plot to dialogue are routinely flouted, as is the notion that a work of literature should be unified and coherent. The resulting scenes, actions, and dialogue are usually disconnected, repetitive, and intentionally nonsensical. Such works might be comic were it not for their obviously and grotesquely tragic dimensions. The genre has its roots in such literary movements as surrealism and expressionism and owes a great debt to the works of Franz Kafka. It developed in France during the 1940s in the novels and philosophical writings of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. The theater of the Absurd emerged around 1950 with Eugene Ionesco's La cantatrice chauve (The Bald Soprano) (1954), in which, not surprisingly, there is no soprano, let alone a bald one. Equally influential was Samuel Beckett's play Waiting for Godot (1954), in which two tramps wait in vain for someone who may not even exist – and with whom they are not even sure they have an appointment. Several novels written during the 1950s and 1960s in Great Britain and the United States contained Absurdist elements, but most Absurdist works have been written as plays. Harold Pinter was primarily responsible for developing British Absurdist theater; Edward Albee is America's leading Absurdist playwright. FURTHER EXAMPLES: Jean Genet's Le balcon (The Balcony) (1957), Edward Albee's The Sandbox (1959), and Harold Pinter's The Homecoming (1965). Joseph Heller's Catch-22 (1961) is at once a popular novel and an Absurdist work. Source 3: Harmon, William and C. Hugh Holman. A Handbook to Literature. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1996. 518. Print. A term invented by Martin Esslin for the kind of drama that presents a view of the absurdity of the human condition by the abandoning of usual or rational devices and by the use of nonrealistic form. It expounds an existential ideology and views its task as essentially metaphysical. Conceived in perplexity and spiritual anguish, the theater of the absurd portrays not a series of connected incidents telling a story but a pattern of images presenting people as bewildered beings in an incomprehensible universe. The first true example of the theater of the absurd was Eugene Ionesco's The Bald Soprano (1950). The most widely acclaimed play of the school is Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot (1953). Other playwrights in the school, which flourished in Europe and America in the 1950s and 1960s, include Jean Genet, Arthur Adamov, Edward Albee, Arthur Kopit, and Harold Pinter. See ABSURD; BLACK HUMOR. [Reference: Martin Esslin, The Theatre of the Absurd, 3d ed. (1980).] ABSURD: In contemporary literature and criticism, a term applied to the sense that human beings, cut off from their roots, live in meaningless isolation in an alien universe. Although the literature of the absurd employs many of the devices of expressionism and surrealism, its philosophical base is a form of existentialism that views human beings as moving from the nothingness from which they came to the nothingness in which they will end through an existence marked by anguish and absurdity. They live in a world in which there is no way to establish a significant relationship between themselves and their environment. Albert Camus' The Myth of Sisyphus is one central expression of this philosophy. Extreme forms of illogic, inconsistency, and nightmarish fantasy mark the literature expressing this concept. The idea of the absurd has been powerfully expressed in drama (see ABSURD, THEATER OF THE) and in the novel, where Joseph Heller, Thomas Pynchon, Gunter Grass, and Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., have practiced it with distinction. See antihero; antinovel. [References: Arnold P. Hinchcliffe, The Absurd (1969); Wolodymyr T. Zyla, ed., From Surrealism to the Absurd (1970).] BLACK HUMOR: The use of the morbid and the absurd for darkly comic purposes in modern literature. The term refers as much to the tone of anger and bitterness as it does to the grotesque and morbid situations, which often deal with suffering, anxiety, and deah. [Reference: Max F. Schultz, Black Humor Fiction in the Sixties (1973).]