SCCR/30/

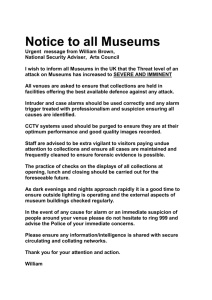

advertisement