Appendix 4 Single cases with follow-up Reference, country, funding

advertisement

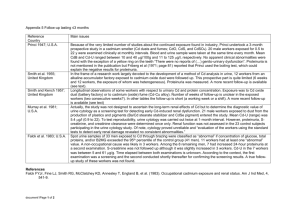

Appendix 4 Single cases with follow-up Reference, country, funding Purpose, design, follow-up Subject, exposure Endpoint, results Nicholson et al. 1997 Australia Division of Adult Intensive Care, Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney. To report a case who may have been exposed to high Cd levels at the workplace. Case report with a 10-week follow-up on the intensive care ward. No later follow-up was identified. The 43-year-old asthmatic male patient, smoker of 20 cigarettes/day, sought medical attention because of acute respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms, which suggested poisoning. Therefore, a toxicology screening including heavy metal was carried out. Cd-U was 438 nmol/l (reference range 0-20). The increased Cd-U did not trigger confirmatory determinations and a screening of co-workers was suggested but not considered advisable by the employers. Nonetheless, Cd fumes inhaled at the crematorium where the patient worked were suspected to be the source of exposure. The patient presented with the aforementioned symptoms. There was no symptom or sign suggesting CKD. After laparotomy, “multi-system organ failure” with acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy occurred. S-creatinine was 0.15 and 0.12 mmol/l on admission and at discharge, respectively. Histology of the kidney biopsy is not described. The authors conclude that “the patient showed evidence of low-level exposure, which was exacerbated by acute exposure to high levels.” The final diagnosis was “cadmium poisoning in a crematorium worker”. Meerkin et al. 1976 Australia Department of Chemical Pathology, Auckland Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand “We present a patient with clinical and biochemical evidence of chronic cadmium poisoning.” Case report of hospitalization in June 1974. Proteinuria was determined again in 1976 and clinical data are presented till 1980 (De Silva PE and Donnan MB 1981) (Table 1). Male 63-year-old worker smoking at least 20 cigarettes/day for 45 years, excessive alcohol intake. Exposure to cadmium carbonate for 11 years. Cd-B and Cd-U: 7.3 g/100 ml and 120 g/l (reference range: 0.3-5.4 and 7-22, respectively). Admission to hospital for “acute bronchitis”. “On examination he had the characteristic physical findings of chronic obstructive airways disease, but there was no other clinical abnormality.” Blood pressure: 140/90 mmHg, FEV1/VC: 55%.Plasma creatinine: 0.15 mmol/l (reference range: 0.04-0.11); creatinine document1 Page 1 of 10 clearance: 0.4 ml/sec (reference range 1.5-2.5 ml/sec). U-protein: 1.98 g/day (reference range: 0.1 g/day). Proteinuria in Dec. 1976: 1.3 g/day (reference range: NI). Plasma urea, bicarbonate, calcium, and phosphorus in the reference range. Aspartate amino transferase and alkaline phosphatase activity were increased and borderline, respectively. Anemia: NI. Etiological differential diagnosis or biopsy: NI. Follow-up regarding GFR: NI. Thus, it is unclear whether the patient really had a low creatinine clearance for more than 3 months or whether the low clearance was due to the acute condition. No CKD related-clinical symptoms or signs or CKD requiring treatment because of too low a GFR or complications of CKD (e.g., anemia, hyperparathyroidism, or hypertension) is reported either at hospitalization or during follow-up. Lauwerys et al. 1979 Belgium Research programme funded by the Commission of the European Communities (since 1972) To report on a follow-up. Case report; 6-year follow-up (1972-1978); 5 examinations, 3 of which after removal from exposure (1974) 58.7-year-old male worker (1st examination; 1972), who was identified through studies in the frame of a research programme on renal effect of Cd (beginning: 1972; total population 310 workers). About 100 workers were found to have signs of Cd-induced renal disturbance. The case reported in the publication was exposed to CdO dust and fume. He had clear signs of glomerular and tubular lesions at baseline and was removed from exposure in 1974 because of his Cd body burden. Time between removal from exposure and last examination was 3.4 years. At baseline (1972), duration of exposure was 21.2 years (23.5 at removal), Cd-B and Cd-U were 3.7 g/100 ml and 32.2 g/g creatinine, respectively. In 1978, Cd concentration in liver and kidney cortex was 81 and 186 ppm, respectively. Exposure to Pb and Hg was assessed. Etiological differential diagnosis or biopsy: NI. The worker had apparently no clinical symptom. Blood pressure: 145/95 (baseline). Proteinuria (mg/g creatinine): 1086, 973, 822, 643, 599 at the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th examination, respectively. Albuminuria (mg/g creatinine): ND, 37.7, 117, 85.4, and 35.9 at the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th examination, respectively. Creatinine clearance (ml/min): ND, 98, ND, 81, ND at the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th examination, respectively. Transferrin, IgG, and B2MG were also increased. Reference values are always indicated and non-exposed subjects were examined at each survey. “The results do not show any improvement of the intensity of the kidney damage.” Nevertheless, the authors do not state there was a deterioration of kidney function either. Senft et al. 1990 Czechoslovakia Klinik für Arbeitsmedizin des Universitätskrankenhauses Pilsen; Kreishygienestation Klatovy; Kreishygienestation Frydek-Mistek; Institut für Kernforschung Rez Description of a case in whom tissue Cd concentrations were available. Case report with 5-year follow-up in the frame of periodic health examinations in a group of about 100 workers. 49-year-old man exposed to CdO in the production of Ni-Cd accumulators. Total duration of exposure was about 27 years. Cd-B (available in 1986 only) amounted to 20 g/l. Cd-U was increased (39, 87, 25 g/l). At necropsy, Cd concentrations in liver (165.2 g/g) and whole kidney (244.8 g/g) were greatly increased. document1 Page 2 of 10 The patient suffered from hypertension since 1984 (blood pressure repeatedly up to 200/110 mmHg). U-B2MG was slightly elevated in 1982, 1984, and 1986, whereas S-B2MG was within the reference range (1-2 mg/l) and decreased slightly in the course of the 5 years (from 1.48 to 0.92 mg/l). Death in 1987 (suicide). Mild osteomalacia at necropsy (no differential diagnosis). Kidney and liver: no histological examination (technical reasons). There is no mention of cases of kidney failure or of uremia. Devulder et al. 1978 France General medicine and nephrology unit and institute of occupational medicine; C.H.U. (Lille) To describe a case with long-standing exposure to Cd and renal biopsy. 43-year-old man having worked in a Zn and Cd plant for 25 years. Cd-U was 135 µg/24 hours. The patient complained about the recent occurrence of impotence, which was suspected to be due to chronic Cd poisoning. Although the kidney function was normal (neither renal insufficiency, no proximal tubular damage), a renal biopsy was carried out because of the increased Cd-U level. Light microscopy showed a mild focal damage of the proximal convoluted tubules (atrophy, disappearance of the brush border at some places, rare mononuclear infiltration and collagenous sclerosis of the peri-tubular interstitium) but no glomerular damage. Electron microscopy confirmed proximal tubular damage and showed little glomerular and distal tubular damage, and calcium deposits. Blood vessels were not described. No further clinical data was reported. Neither a differential diagnosis nor the clinical significance of the biopsy findings in a patient without proximal tubular damage and renal insufficiency were discussed. Kliem et al. 1996 Germany Nephrology Unit, Medical School, Hanover To illustrate a review about Cd-induced tubulointerstitial nephropathy. Case report with an 19-year follow-up (1978-1997) 66-year-old male patient having worked from 1956 to 1974 as a furnaceman in a Cd plant. Cd-U and Cd-B were measured and found to be still “increased” in 1994 (the concentrations are not indicated). S-creatinine was 110 and 550 mol/l in 1978 and 1997, respectively. Urinary protein (0.2 g/day) and glycosuria were found. Kidney biopsy (1980): interstitial fibrosis and lymphocytic infiltration. No further information is given Baader 1952 Germany Professor of Pathology and Clinical Aspects of Industrial Disease, University of Muenster document1 Page 3 of 10 To present a “case of chronic Cd poisoning with curious post-mortem findings.” Case report. Follow-up of some years (exact number not indicated). The worker was a tool setter exposed to CdO dust for 16 years in an accumulator factory, who gave up his Cd work in 1946. At necropsy in 1950, Cd was determined and “Whereas the cadmium content of 10-15 gm. organic substance of lungs, heart and spleen varied between 5 and 30 gamma (=g), was practically absent in the brain, it amounted to 1430 gamma in the liver and 1750 gamma in the kidneys.” The patient died at the age of 39 under the clinical picture of dextrocardial failure. At necropsy, “examination of the lungs revealed bullous emphysema, fibroplastic peribronchitis and a primary peribronchial interstitial pneumonia of all lobes of the lungs, and purulent bronchitis.” In the kidneys, signs of “toxic nephrosis” were found (no further detail). A proteinuria had been found at a previous examination after giving up work. The author concluded that “Definite evidence that cadmium is basically responsible for the pathologic picture of this intoxication is indicated by the finding of cadmium in the liver and kidneys.” Ando et al. 1996 Japan Department of Hygiene, Nagoya University School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan To present “a patient with cadmium pneumonitis in whom consecutive urinary cadmium concentrations were measured after the exposure.” Case report; 25-day-follow-up. No later determination. Chemical pneumonitis after exposure to Cd due to soldering with silver alloy containing Cd. Information on occupational history is limited (”assembled machines on his own”). Cd-U (spot sample): 24.0 and 5.5 g/l on day 5 and 23, respectively Kidney function tests were carried out (glomerular and tubular, e.g. U-B2MG) but the main medical problem was acute Cd pneumonitis. Pulmonary edema was diagnosed (PaO2 7.1 kPa under 100% oxygen) requiring insertion of an endotracheal tube for mechanical ventilation. “A urinalysis indicated mild proteinuria and the sediment contained some renal tubule cells.” “(…) the abnormal urinalysis findings on admission suggested that the renal tubular damage was caused by inhaled cadmium before admission. On the other hand, his serum creatinine level and creatinine clearance remained normal throughout the disease course.” On day 24, “The laboratory findings for urine and blood were normal.” Previous measurements are not available.” The “transient renal impairment” was considered as consistent with Cd-induced renal toxicity. The possible role of drugs is touched on, whereas the effect of hypoxemia is not discussed. Harada et al. 1978 Japan Reporting Organizations: Kansai Occupational Health Technology Center and Department of Hygiene and Public Health, Osaka Medical College To summarize the “key points” regarding a case with follow-up (1972-1974). document1 Page 4 of 10 51-year-old worker in 1972. The patient “had completed 21 years of service at this Cd-based pigment manufacturing plant exclusively in the sintering operation”. Initially, Cd-U was 142 g/l. Then, Cd-U decreased. Lowest concentration was around 30 g/l. Proteinuria was always positive (sulfosalicylic and trichloracetic acid) and a tubular proteinuria was ascertained. “Urea nitrogen” was always within the normal range. Minor degeneration of the renal tubules was found on biopsy. An “image of hardened glomeruli” was described in 1974 but had not been observed on the 1972 biopsy. Etiological differential diagnosis: NI. The patient was diagnosed with “probable chronic Cd poisoning”. This case of “probable chronic Cd poisoning” is not mentioned any longer in the publication about the longer follow-up (1972-1986). Kido et al. 1990 Japan Department of Hygiene and Public Health, Kanazawa Medical University; lshikawa Prefecture Health Authority These authors presented more details about the most severe case from their case series. Cd-U under diuretics was 7.9 g/g. In 1988, the 80-year-old woman was diagnosed with kidney failure (CKD-G5). She did not suffer from diabetes mellitus or other systemic diseases. She had generalized edema, metabolic acidosis, and normocytic and normochromic anemia. Creatinine clearance and proteinuria were 10.9 ml/min and 1934 mg/g creatinine, respectively. Information on investigations excluding causes other than Cd is rather scarce (arteriosclerosis, ischemia). Sakurai 1978 Japan In his review (page 142), this author summarizes findings from“(…) follow-up studies on one case of chronic cadmium poisoning which had undergone thorough medical examinations. The patient showed decreased urinary concentration and PSP excretion, but urea nitrogen, nonprotein nitrogen and creatinine levels in serum and blood pressure were found to be almost normal.” Two biopsies were done in this Cd worker. “The pathological diagnosis in 1971 was slight degeneration of the renal tubules. In 1973, however, it was diagnosed as arteriolar nephrosclerosis with interstitial nephritis and proximal renal tubular atrophy. During the same period, the clinical and laboratory findings of the patient did not change appreciably except for a moderate increase in proteinuria and decrease in urinary cadmium concentration.” Gil et al. 2011 Korea Department of Internal Medicine, Soonchunhyang, University Cheonan Hospital To present a patient diagnosed with “chronic Cd intoxication” treated by chelation (intravenous administration of Ca++-EDTA with and without glutathione). Case report with a 6 month follow-up. document1 Page 5 of 10 54-year-old man having worked in a factory producing compressors for air conditioners from 1977 to 2001 (no further information). In 2001, a routine monitoring showed “abnormally high Cd-B levels” (concentration not reported). The patient was then immediately entered into a program for the treatment of Cd intoxication, and he no longer worked in the factory.” Cd-U was 50.1 and 10.9 g/day at the beginning of and 6 months after chelation therapy, respectively, whereas Cd-B increased from 4.4 to 5.7 g/l. In 2001, the patient had reported intractable bone pain, insomnia, and general weakness. Main complaint in 2008 was “generalized bone pain, worse at night and relieved during the day time especially by walking”. Chelation was undertaken in 2008. S-creatinine was 0.9 mg/100 ml and did not change during followup. The urinary protein/creatinine ratio fluctuated between 108.81 ± 13.95 and 117.44 ± 28.67 mg/g (no reference range is given). Mean U-B2MG before chelation fluctuated widely (3378±1814 ng/mg). No explanation regarding etiology of the subjective complaints is given. Fernandez et al. 2010; Fernandez et al. 2010; Nogue et al. 2004 Spain Unidad de Toxicologia, Hospital Clinic I Provincial, Barcelona, Spain To describe the case of a welder exposed to Cd fumes, who was diagnosed with a focal IgA mesangial glomerulonephritis. Case report with an 8-year follow-up (2002-2010) described at baseline (Nogue S et al. 2004 RM 36 832), follow-up (Fernandez J et al. 2010 RM 902), and summarized in an abstract (Fernandez J et al. 2010 RM 979). 47-year-old male patient in 2010, former smoker. He had worked for 12 years as a welder using electrodes consisting of silver, cadmium (25%), copper and zinc. In 2002, Cd-B and Cd-U were 45 g/l and 85 g/g creatinine, respectively. The patient was dismissed from his job in 2002. There had been 3 health examinations during the 12 years at work as a welder. S-creatinine and examination of urine had been “normal”. In 2002, the general practitioner found a proteinuria with microhaematuria and referred the asymptomatic patient for investigations showing the following: Proteinuria (2 g/24h) with microhaematuria but no kidney disease in the clinical and family history, no diabetes, no drug. Blood pressure: 105/65. U-B2MG, urinary N-acetylglucosaminidase, retinol-binding protein, creatinine clearance (137 ml/min), anti-DNA, anti-tissue antibodies, complement, and abdominal ultrasound were unremarkable. Serum immunoglobulins were within normal limits, except for an increased IgA level. A renal biopsy was carried out and the patient diagnosed with IgA mesangial glomerulonephritis. Despite treatment and removal from exposure, proteinuria persisted (0.28 g/24h in 2010) but good renal function was maintained (S-creatinine: 1.0 and 1.03 mg/dl in 2002 and 2010, respectively) The authors recommend to keep patients with IgA mesangial glomerulonephritis “apart from exposure to nephrotoxic substances”. Note that as microproteinuria and N-acetyl--D-glucosaminidase activity were in the reference range, the classical Cd-induced tubular effect was absent. Blainey et al. 1980 United Kingdom Queen Elizabeth Hospital and Department of Pathology, University of Birmingham Osteomalacia has been described in a man with tubular proteinuria (deceased after a cardiac arrest at age 71 years in 1976), who was included in the group of 41 workers described by Adams RG et al. (table 14). document1 Page 6 of 10 Exposure lasted 36 years and was confirmed by measurements (Cd-U, Cd-liver, Cd-kidney). The worker was diagnosed with an adult Fanconi syndrome. Proteinuria (last examination) was 1.0 g/24h with a typical renal tubular pattern of small molecular weight protein. S-creatinine concentration was stable ( : 214.4 µmol/l; last examination: 202 µmol/l). A main feature of this case was the stability of the renal findings despite a 24-year-long follow-up of a proteinuria detected for the first time in 1952. “The dietary history indicated a remarkably low calcium and vitamin D intake.” At necropsy, “The kidneys showed severe postmortem autolysis. There was recognisable chronic ischaemic damage, with numerous small scattered groups of completely hyalinised glomeruli in the subcapsular zone with interstitial lymphocytic infiltration about these areas. The remaining glomeruli were normal. The autolytic changes made assessment of the renal tubules impossible. The small arteries showed pronounced fibroelastic intimal thickening due to age changes.” Extensive atheromathous changes were found in the vascular system. “The mechanism of development of the severe acquired Fanconi syndrome was thought to be a combination of dietary calcium and vitamin D deficiency and impaired calcium absorption from abnormal vitamin D synthesis, related to the cadmium deposition in the renal tubules, which also caused the defect in renal tubular reabsorption.” Bonnell 1955; Bonnell et al. 1959 United Kingdom Department for Research in Industrial Medicine (Medical Research Council), London Hospital. To report the history of a 54-year-old man. The worker was identified in the frame of investigations in factories manufacturing Cu-Cd alloys and had been under observation for 18 months before death (May 1954). “(…) from 1920 to 1952 he had worked casting an alloy of copper and cadmium. He had also cast brass and bronze during this time. He had always worked on the pit-fire furnace and for the greater part of this time was responsible for casting the “master alloy” containing 33% cadmium with copper. He had not worked since November, 1952.” Cd-U (April 1953) was 30-40 g/24h. Cd-kidney and Cd-liver were 6.15 and 33.01 mg/100g (wet weight), respectively (no control range is indicated). The patient was diagnosed with chronic renal failure with “a pronounced uraemic odour in the breath”, LMW proteinuria, and a moderate degree of emphysema. There was no hypertension, past history of hematuria or renal disease. “(…) granular contracted kidneys were found at necropsy. The histological changes were non-specific (…).” “On microscopic examination of the kidneys Professor Dorothy Russel was of the opinion that the changes were indistinguishable from the nephritis repens of Bright’s disease (…). Martin et al. 2009 U.S.A. Institute of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Medicine, West Virginia University; Health Effects Laboratory Division and Division of Respiratory Disease Studies, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To report a case of elevated Cd-B of a painter who was also a cigarette smoker. Case report with a 5-year follow-up (2000-2005) document1 Page 7 of 10 A 45-year-old smoking (1.5–2 packs of cigarettes/day for 23 years) male paint technician was identified with an elevated Cd-B of 5.9 g/l through routine monitoring (reference range for smokers: 0.6-3.9 g/l; occupational exposure limit: 5 g/l). His work involved spraying paint containing CdS pigment onto jet aircraft. From October 2000 through December 2003, his Cd-B ranged from 3.1-4.3 g/l. In April 2005, the level rose to 5.9 g/l and because of potential work exposure, he was redeployed to another job without Cd exposure. Nevertheless, his Cd-B remained at 6.1 g/l 7 weeks later. Cd-U was not increased. No non-occupational exposures to Cd were identified with the exception of smoking. As he had recently changed the brand of cigarettes he smoked, he switched back to his original brand and reduced his consumption to 1 pack per day. Twelve weeks after the initial elevated result, his Cd-B had fallen to 2.9 g/l. Eight weeks after returning to his original position with Cd exposure, Cd-B was 3.4 g/l. Measuring the Cd content of the tobacco showed that the new brand of tobacco had a greater Cd concentration than the old one (average: +0.397 g/g). No elevation of U-B2MG, blood urea or creatinine was noted at any point (no detail is given). The authors conclude that “These results suggest that the consumption of different brands of cigarettes can lead to marked variations in whole-blood cadmium levels including elevation above OSHA biological limits.” Garry et al. 1986 U.S.A State of Minnesota and Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Minnesota; NIH grant ESO 1629, and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. No explicit purpose is stated. However, study planning and examinations focus clearly on Cd effects on the kidney. Case report with follow-up >23 months (from the first Cd determinations in blood or urine to autopsy). 57-year-old white woman, heavy smoker for 20 years, having worked for 20 years in the assembly of nickel-cadmium batteries. In the last years of her employment, a biologic monitoring program was established. Initially, she had a Cd-B of 69 g/l (normal <7), a Cd-U of 31.0 g/l (normal <10), and a B2MG level of 10’700 g/L (normal <4-370). “As a result of the initial biological monitoring, the patient was transferred to another area of the plant in order to lessen her exposure to cadmium.” Fifteen months later, Cd-B and Cd-U were 20.5 g/l and 26.5 g/l, respectively. The B2MG concentration was 31751 g/l. Frozen aliquots of liver and kidney were analyzed by neutron activation analysis. Cd-liver and Cd-kidney concentrations were about 138 and 167 g/g wet weight, respectively (reference ranges: <5.8 and <33.2, respectively). The liver metallothionein concentration was at least 10-fold greater than expected. The patient suffered from a stomach neoplasm with involvement of lung and bone. She was treated with radiation and chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine, mitomycin, and 5-fluorouracil). At necropsy, the light microscopic study showed the general morphologic findings of proximal tubular dilation with loss of tubular epithelium, whereas the glomeruli appeared relatively normal. In some areas, interstitial fibrosis and attempted regeneration of the tubules were found. Electron microscopic examination showed cytoplasmic vesicles and intramitochondrial deposits resembling late-stage, experimentally induced Cd nephropathy in the rat. The authors conclude: “The light and electron microscopic data recorded in our examination of the kidney are consistent with the data derived from chronic studies of cadmium intoxication in animals. (…) However, we cannot entirely rule out the participation of the patient's cancer chemotherapy in the morphologic results. Adriamycin and the combination of 5- fluorouracil with mitomycin can be nephrotoxic but do not usually produce lesions confined to the proximal tubules. The latter is characteristic of chronic cadmium intoxication.” No test of renal function was reported. document1 Page 8 of 10 Lerner et al. 1979 U.S.A Supported by General Clinical Research Center Grant RR-68-18 and Renal Fund, University of Cincinnati Medical Center “Routine and specialized studies were employed to assess the clinical status, in relation to renal and other organ functions and blood and urine cadmium levels, of a worker with a nine-year cadmium exposure.” Case report with multiple investigations from February 1976 to November 1977 (21 months). 49-year-old white male, heavy smoker, exposed to Cd from 1966 to 1975 in a plant manufacturing pigments. Until 1968 his exposure was primarily to cadmium sulphide and selenide dust. “After 1968 he frequently handled soluble, easily absorbed cadmium compounds. From 1972 until 1975 he had some exposure to cadmium fume.” Between 1972 and 1975, Cd-B was between 5.0 and 8.1 g/100g (reference range: <1). At the end of this time period, a Cd-B amounted to 17.1 g/100g but this could not be explained and was only checked 3 months later with a concentrations of 6.5 g/100g. Cd-U was between 5.2 and 122.0 g/l between 1967 and 1974 (reference range: <2 g/L). After having measured the high concentration of 17.1 g/100g (October 1975) the patient was permanently removed from Cd exposure as a precaution.” At the last examination (November 30, 1977), Cd-B and Cd-U were 3.3 g/100g and 77 mg/l, respectively. Briefly summarized, all symptoms appeared after the patient was told of his 17.1 level and removed from further cadmium exposure. Non-contributory clinical history, no diabetes. Mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease probably associated with smoking. Blood pressure: 90/50. U-B2MG was 1525 g/24h (reference range 30-370), whereas repeated investigations showed no evidence of proteinuria, glycosuria, or elevated S-creatinine. GFR (inuline) was 81 ml/min/1.73 m2 (reference ± SD: 101 ± 10). The authors conclude that “Most probably his weight loss is related not to cadmium or another organic cause but rather to a simple lack of food intake, perhaps voluntary and possibly secondary to a functional anorexia or even to secondary gain factors. The varied symptom complex he displays is not consistent wth chronic cadmium intoxication.” References Ando Y, Shibata E, Tsuchiyama F, Sakai S. (1996). Elevated urinary cadmium concentrations in a patient with acute cadmium pneumonitis. Scand J Work Environ Health, 22, 150-3. Baader EW. (1952). Chronic cadmium poisoning. Ind Med Surg, 21, 427-30. Blainey JD, Adams RG, Brewer DB, Harvey TC. (1980). Cadmium-induced osteomalacia. Br J Ind Med, 37, 278-84. Bonnell JA. (1955). Emphysema and proteinuria in men casting copper-cadmium alloys. Br J Ind Med, 12, 181-95. Bonnell JA, Kazantzis G, King E. (1959). A follow-up study of men exposed to cadmium oxide fume. Br J Ind Med, 16, 135-47. Devulder B, Martin JC, Plouvier B, Le Bouffant L, Tacquet A, Furon D. (1978). Les aspects ultrastructuraux de la nephropathie cadmique humaine et experimentale. Arch Mal Prof, 39, 35-43. Fernandez J, Sanz-Gallen P, Nogue S. (2010). Follow-up of two patients with mesangial IgA glomerulonephritis exposed to cadmium and organic solvents. An Sist Sanit Navar, 33, 309-13. document1 Page 9 of 10 Fernandez J, Sanz P, Nogue S. (2010). Follow-up of 2 patients with mesangial IgA glomerulonephritis exposed to cadmium and organic solvents. Toxicol Lett, 196, S72. Garry VF, Pohlman BL, Wick MR, Garvey JS, Zeisler R. (1986). Chronic cadmium intoxication: Tissue response in an occupationally exposed patient. Am J Ind Med, 10, 153-61. Gil HW, Kang EJ, Lee KH, Yang JO, Lee EY, Hong SY. (2011). Effect of glutathione on the cadmium chelation of EDTA in a patient with cadmium intoxication. Hum Exp Toxicol, 30, 79-83. Harada A, Hirota M, Shibuya Y, Kohno K, Yoshida Y. (1978). Occupational health studies on cadmium workers. Kankyo Hoken Rep, 44, 161-74. Kido T, Nogawa K, Ishizaki M, Honda R, Tsuritani I, Yamada Y, et al. (1990). Long-term observation of serum creatinine and arterial blood pH in persons with cadmium-induced renal dysfunction. Arch Environ Health, 45, 35-41. Kliem V, Lonnemann G, Brunkhorst R. (1996). Durch Nephrotoxine verursachte tubulointerstitielle Nephropathien. Internist, 37, 1116-28. Lauwerys R, Vos A, Roels H, Buchet JP, Bernard A. (1979). Surveillance d'un travailleur ecarte de son poste de travail suite a la decouverte de lesions renales induites par le cadmium [Monitoring of a workman discharged from his place of business following discovery of renal lesions induced by cadmium]. [French]. Arch Belg Med Soc, 37, 137-46. Lerner S, Hong CD, Bozian RC. (1979). Cadmium nephropathy - A clinical evaluation. J Occup Med, 21, 409-12. Martin CJ, Antonini JM, Doney BC. (2009). A case report of elevated blood cadmium. Occup Med, 59, 130-2. Meerkin M, Clarke R, Oliphant R. (1976). Chronic cadmium poisoning. Med J Aust, 1, 23-4. Nicholson G, Fynn J, Coroneos N. (1997). Cadmium poisoning in a crematorium worker. Anaesth Intensive Care, 25, 163-5. Nogue S, Sanz-Gallen P, Torras A, Boluda F. (2004). Chronic overexposure to cadmium fumes associated with IgA mesangial glomerulonephritis. Occup Med, 54, 265-7. Sakurai H. (1978). Epidemiological studies. In: Tsuchiya K, King Sted S, Hamagami CM, eds. Cadmium studies in Japan: a review. Amsterdam, New York, Oxford: Kodansha Ltd.; Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press; Elsevier North-Holland Inc., 133-268. Senft V, Huzl F, Krysl S, Vit M, Kucera J. (1990). Auswertung des Einflusses der Exposition gegenuber Cadmium bei einem Werktätigen in der Ni-CdAkkumulatoren-Produktion anhand biologischer Tests in vivo und des Cadmiumgehalts in den Geweben post mortem. Zentralbl Hyg Umweltmed, 189, 395-404. document1 Page 10 of 10