Arthroscopic Posterior Capsulorrhaphy for Osteoarthritis of the Should

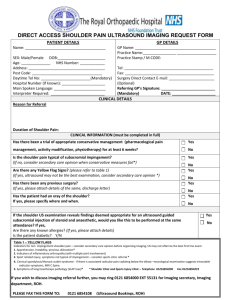

advertisement

Arthroscopic Posterior Capsulorrhaphy for Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder Associated with Posterior Instability: Two to Ten year results ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION: Two seemingly overlooked papers in the orthopaedic literature provided the stimulus for this investigation. In 1981, Rowe and Zarins (2) presented a series of patients with an unusual presentation of shoulder pain, which they treated with capsulorrhaphy, achieving 94% good or excellent results. The patients had been seen by various clinicians with failure to diagnose or sometimes various alternative psychologic or neurologic diagnoses. In 1983, Robert Samilson (3) described the importance of posterior instability and the common appearance of posterior changes, such as posterior slope of the glenoid, posterior Bankart tears and posterior erosion as a common accompaniment of osteoarthritis.(1,4,5,6,7,8,9) He emphasized that delay in diagnosis of posterior instability might be responsible for those changes. As we began to see similar conditions in my practice, we began to think that there might be a connection between these two findings; that perhaps persons with posterior instability might go undiagnosed for years and not recognized until changes of osteoarthritis began to occur as a result of shear forces on cartilage. (10,11) Although much has been reported in orthopaedic studies about the effects of compressive forces on articular cartilage, very little appears relating to shear forces as a cause of injury. We postulate that once the mechanical effects of shoulder instability begin, shear effects cause pathologic changes such as labral fragmentation and chondromalacia. The subsequent inflammatory response may later accelerate the process by virtue of the metabolic changes which act in concert with the mechanical process to accelerate the changes of osteoarthritis. (1) We postulated then, that treating the posterior instability in shoulders with early osteoarthritis that have posterior instability might delay the progression or even halt the progression of the disease. This paper is an attempt to examine that hypothesis. It is not meant to state that all causes of shoulder osteoarthritis are caused by instability but that there may be a group of patients who fit that category METHODS There were 25 patients in the group with a range of age of 44 to 74 years of age. The median age at the time of surgery was 59. Eighty percent (20) were men, 20% (5) were women. 56% had their dominant shoulder involved. 11.5% (3) had injury due to work related incidence. All patients presented with painful various stages of osteoarthritis or advanced chondromalacia of the shoulder and on clinical exam showed evidence of posterior instability. Fig. 1 1 (Fig.1) No patient in this study had been operated previously with a Putti-Platt procedure. One had a previous Bankart procedure done by the author, another had a Magnuson –Stack procedure done by another surgeon 20 years previously. Two had previous anterior dislocations treated non-surgically, one had an AC separation many years previously. Another had an open reduction internal fixation of a humerus fracture four years prior to surgery. No patient had any hardware impingement as confirmed by pre-op x-rays and arthroscopic exam at the time of index surgery. Each shoulder was treated with bilateral examination under anesthesia, arthroscopic exam, debridement, removal of any loose bodies, chondroplasty and posterior capsulorrhaphy. SLAP tears or partial thickness rotator cuff tears, when present, were included, but any patient with anterior Bankart tears or full thickness rotator cuff tear repairs were eliminated from the study.(12) On average, the 25 patients scored 7.5 on the pre-op simple shoulder test and rated their pre-op pain about five on a scale of 0-10 on the visual analog scale Many patients at the time of the study could have been considered candidates for resurfacing or replacement arthroplasty. All patients in this series had some osteoarthritis on the glenoid of the treated shoulder with at least Grade III and some 2 degree of Grade IV posterior chondromalacia with functional range of motion and reasonably normal contours of the glenoid and humerus. (Reasonable contours is defined as no flattening of the humeral head or large glenohumeral joint osteophyte formation.) The humerus was usually involved with one grade less of chondromalacia than the glenoid. During the earlier stages the wear pattern on the humerus tended to be on the central or slightly anterior portion of its articulating surface. Some patients had developed some posterior erosion or posterior slope of the glenoid. All patients had X-ray or MR evidence of glenohumeral joint arthritis and evidence of primarily posterior instability on pre-op and intraoperative exams. Surgery began with an examination under anesthesia of both shoulders to assess range of motion and to confirm the diagnosis of posterior instability. Arthroscopic treatment included a subacromial exam and a thorough glenohumeral examination through posterior and anterior portals, removal of any loose bodies, debridement, abrasion chondroplasty using a full radius synovial resector to freshen bony surfaces to bleeding bone, and to trim loose articular cartilage to stable margins. A capsulorrhaphy was then done using a combination of monopolar radiofrequency treating selected areas with a striping technique, then with suture augmentation using absorbable or non-absorbable suture in selected areas to complete the shoulder stabilization. (12,13,14) Post treatment exam under anesthesia showed improvement of the instability with negative sulcus and drawer signs. No pain pumps were used in the study but each patient was given a single intra-articular injection of bupivacaine 0.5% before leaving the operating suite. The patient was placed in a well padded, abduction pillow sling (Don-Joy, Breg). before leaving the operating room. The post-operative management was divided into two phases, a six week recovery period involving healing and range of motion, followed by a six week rehabilitation period involving strengthening and return to use, after which patients were allowed unrestricted activities, including sports. A strict post-operative regimen was developed and used based on the author’s experience and that of Wilk and Andrews (15), with sling wear for six weeks, pendulum exercises beginning the day after surgery, range of 3 motion exercises beginning at the second through the sixth week and progressive resistive exercises beginning at the sixth week with discontinuation of the sling. In most cases physical therapy was augmented by a home exercise program. Controlled range of motion during the healing phase was considered important to nourish the joint and avoid stiffness. The goal was to reach functional, if not normal range of motion by the end of the sixth week during the period when the capsule would be most stretchable. (15,16) RESULTS Of the 25 patients, three were dropped from the analog pain and function scales test, because they did not complete preoperative analog pain and function scales; however, the same three were calculated in the Simple Shoulder Test as they had completed that pre-op evaluation. All patients in this study had a pre-op and a post-op Simple Shoulder Test performed at final follow up. Statistical Analysis SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences computer program) was used to conduct the analysis. The paired-sample t-test was used to analyze the mean differences for the analog pain and function scales as well as the Simple Shoulder Test. Patient Satisfaction Form (Fig. 2, Fig. 3) 4 Simple Shoulder Test (SST) There was significant improvement in the SST score (p < 0.001). The patients performed on average of 7.5 of the twelve functions on the SST before surgery and a mean of 10.3 of the functions at the time of the last follow-up, with a mean difference of 2.8. Our sample size is small, but a side by side observation of the preoperative and postoperative shoulder functions shows a noteworthy increase with all the functions evaluated in the SST. The top four increases sleep comfortably (46.1%), wash opposite shoulder (42.3%), lift 8 pounds to shoulder level (34.6%), and shoulder comfortable with arm rested at side (30.8%). The four smallest increases in shoulder functionality are place a coin on a shelf at shoulder level (7.7%), lift a pint of liquid to shoulder (7.7%), carry 20 pounds at your side (11.5%), and work full-time at your regular job (11.5%). (Fig.4) VAS For Pain and Function There was a significant decrease in pain of the shoulder at long-term follow-up.. The mean initial pain scale was 5.22 ± 2.02 (range 1 to 7) and the mean follow up pain scale was 2.87 ± 2.22 (range 0 to 8). The mean difference of the pain scale was 2.35 (p < .001, 95% CI). There was also a significant increase in functionality of the shoulder at 5 the time of the follow-up visit . The mean initial function scale was 4.35 ± 1.99 (range 2 to 8) and the mean follow up function scale was 8.57 ± 0.992 (range 5 to 10). The mean difference of the function scale was 4.27 (p < .001, 95% CI). Overall this indicates that the procedure was a success with these patients. (Table 1) Only four patients were unable to return to their previous level of work. One of these had been a work injury. Of 25 patients, one reported that he was not satisfied with the results of the procedure and would not have it again if the choice were given to him. This patient has not come to a shoulder replacement or any further surgery. For uncertain reasons he did not have an abrasion chondroplasty as part of his surgery. In spite of that, he has managed to lead a very active life-style showing a significant improvement in the post-op Simple Shoulder Test scores. Of the remaining 24, many were enthusiastic and grateful about having had the procedure on their shoulder. Twenty-two patients returned to “full activity including sports at the 80% or better level. In some cases this included tennis, soft ball, basket ball. One had returned to national level tournament amateur golf. One patient later came to having a shoulder replacement. There were no infections, axillary nerve injuries, stiff shoulders, capsular injuries or chondrolysis. DISCUSSION Up to now the only surgical treatments available for osteoarthritis of the shoulder have been capsular release (17) and fascial (18) or replacement arthroplasty (19) when conservative means such as physical therapy with oral anti-inflammatories or injections have failed. Complications of replacement arthroplasty in a young patient, a major surgery, often requiring later revisions has not been a satisfactory choice. Our approach to treatment of the problem offers two advantages. First it does not burn any 6 bridges for future treatment. Secondly, management can be totally arthroscopic. Even a few years spent avoiding replacement arthroplasty can be a definite advantage. So far as we know, no other such approach treating arthritic shoulders has been described. While arthroscopic fascial arthroplasty has been described as a possible treatment for this condition, the results have not been durable or consistent, and the procedure is difficult for even the experienced surgeon to perform. Ours is a simple approach to this perplexing problem. There is a learning curve of how much and where tightening should be achieved, but the use of thermal energy thus allows some forgiveness of this problem, because it allows stretching without tearing the tightened capsule.. It could be done using an open procedure (28) or an arthroscopic suture capsulorrhaphy, the latter being the preference of those two choices because open capsulorrhaphy can often over-tighten the capsule. Over-tightening (29) is a complication which could doom the success of the procedure. The posterior capsule, however, is generally more forgiving than the anterior capsule. To this author’s knowledge reports of arthritis resulting from over-tightening have been due to anterior tightening (e.g. Putti-Platt). A shoulder already on the pathway to replacement has little to lose in the face of potential gain. A paradox existed with the Simple Shoulder Test with other parts of the post op evaluation in which three patients appeared to have a lesser score on their Simple Shoulder Test post op than pre-op but had improved function or less pain on the visual analog scale and expressed satisfaction with having had the procedure. Part of this paradox can be explained by question number 12 and the fact that many office workers have little physical demand on their shoulders are able to work whereas a laborer’s work can be significantly affected by shoulder osteoarthritis. We suggest that question 12 on the simple shoulder test be changed to “ Able to perform maintenance and repair tasks around the home”. Since many work positions are non-physical, “return to work” may not be a reliable indication of physical capacity, but almost everyone does routine household chores. The patients which did show a discrepancy in the simple shoulder test did notice subjective improvement in their overall function. One of these was 7 enthusiastic about the surgery, saying that it made a “huge difference from his preoperative condition” All except the one mentioned above would have the surgery again if given the choice. We developed the “Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire” to help correct this SST discrepancy (Fig.3) We feel there were no failures in this series of patients with the methods described. The one patient who did come to a shoulder replacement gained seven years of relief before requiring a hemi-arthroplasty. That patient was grossly overweight and had become wheelchair bound, thereby relying heavily on her upper extremities for mobility, placing added stress on an already impaired shoulder. This study has some weaknesses. The patient number is limited. The study is not blinded, being presented by a single author and surgeon. The procedure is not compared with other methods of treatment. The analysis of the results is accomplished with a visual analogue scale as to pain and function, a questionnaire evaluating post-op activity level, quality of life and patient satisfaction and the Simple Shoulder Test. For purposes of simplicity and convenience in a community office practice other more complex shoulder scales were not used. In a pre-operative trial many of our patients refused to answer the mental health parts of SF36 questionnaire making its use impossible. The Simple Shoulder Test and Visual Analogue Scale have been shown to be satisfactory indicators of success in other clinical studies. Patient satisfaction is considered a good indicator of success or failure. (30) CONCLUSION This study demonstrates that at least in some cases posterior instability may be a cause, not necessarily a result of osteoarthritis. This condition of posterior instability in its early stages may require a high index of suspicion on the part of the evaluating surgeon. We present a simple approach to treatment for many patients who may find simple relief of a very difficult and disabling problem while still in the productive years of their life. 8 REFERENCES 1. Iannoti, Joseph, Williams, Jr., Disorders of the Shoulder, Diagnosis and Management, Second Edition, Vol. I, 2007, Edited by Lippicott, William and Wilkins, Chapter 18, David N. Collins, pp 570-573. 2. Rowe CR and Zarins B. “Recurrent Transient Subluxation Of The Shoulder”. J Bone Joint Surg 1981; 63A(6): 863-872. 3. Samilson RL, Priet V: “Dislocation Arthropathy of the Shoulder”. J Bone Joint Surg AM. 1983; 65: 456-460 4. Edelson JG: “Patterns Of Degenerative Change In The Glenohumeral Joint”, J Bone Joint Surg Br, Mar 1995; 77-B: 288 - 292. 5. Habermeyer, P., Magosch, P., Luz, V., Lichtenberg, S. : “Three Dimensional Glenoid Deformity In Patients With Osteoarthritis: A Radiographic Analysis.” JBJS, Vol. 88, #6, June 2006, pp 1301-1307. 6. Mullali, A.B., Beddow, FH, Lamb, GHR: “CT Measurement of Glenoid Erosion in Arthritis.” J.B.J.S., Vol. 6B, 1994, pp 384-388. 7. Nightingale EJ, Walsh WR: “Radiofrequency Energy Effects on the Mechanical Properties of Tendon and Capsule – Arthroscopy.” The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery December 2005 (Vol. 21, Issue 12, Pages 1479-1485) 8. Spencer, Edwin E, Jr., Valdevit, Antonio, Kambic, Ellen, Brems, John J., Iannoti, Joseph P.: “The Effect of Humeral Component Anteversion on Shoulder Stability with Glenoid Component Retroversion”, JBJS, Vol 87-A, April 2005 pp 808-814 9. Buckwalter, JA, Menkin, HJ,: “Articular Cartilage”, JBJS, Vol 79-A, #4, April 1997, pp 600-632. 10. Buckwalter, JA: “Shear Effect Forces on Articular Cartilages”, Personal Communication. 11. Rockwood, C, Jr., Matsen, F III, Wirth, M A., Lippitt, S B: The Shoulder, Third Editions, Vol One, 2004, Elsevier, pp 308-309 12. Rockwood, C, Jr., Matsen, F III, Wirth, M A., Lippitt, S B: The Shoulder, Third Editions, Vol One, 2004, Elsevier, pp 304-305 13. Aneja A, Karas SG, Weinhold PS, Afshari HM, and Dahners LE: “Suture Plication, Thermal Shrinkage, and Sclerosing Agents: Effects on Rat Patellar Tendon Length and Biomechanical Strength.” Am. J. Sports Med., Nov 2005; 33: 1729 - 1734. 14. Abrams, Jeffrey: “Advanced Reconstruction of the Shoulder, First Edition”, 2007, AAOS, Chapter II, Arthroscopic Posterior Shoulder Repair, pp 11-19. 15. Wilk, Kevin E., Reinhold, Michael, Dugass, Jeffry, Andrews, James R.: “Rehabilitation Following Thermal Assisted Capsular Shrinkage Of The 9 Glenohumeral Joint: Current Concepts.” Journal of Orthopaedics and Sports Physical Therapy, Vol 32, #6, June 2002, pp 268-287. 16. Lu, Yan, Hayashi, Kei, Edwards, Ryland B. III, Fanton, Gary S., Thabit, George III, Markel, Mark D. : “The Affect of Monopolar Radiofrequency Treatment Pattern on Joint Capsular Healing.” Am Journal Sports Medicine, Vol 28, #5, 2000 pp 711-719 17. Richards D, Burkhart S: “Arthroscopic Debridement and Capsular Release for Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis, Arthroscopy”, The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, Vol 23, No. 9 (Sept), 2007: pp 1019-1022 18. Cameron, B D., Iannoti, J: “Alternatives to Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in the Young Patient.” Tech Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, Vol 5, #3, September 2004: pp 135-145. 19. McCarty III LP, Cole BJ: “Non-arthroplasty Treatment of Glenohumeral Cartilage Lesions, Arthroscopy.” The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, September 2005 (Vol. 21, Issue 9, Pages 1131-1142) 20. Brillhart, A.T. “Complications of Thermal Energy”. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine, July 1998, Vol 6, #3, Saunders and Co., pp 182. 21. Fanton, G.S. “Arthroscopic Electrothermal Surgery of the Shoulder”. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine, July 1998, Vol 6, #3, Saunders and Co. pp 139-146, 22. Foster, T.E., Elman, M. “Arthroscopic Delivery Systems for Thermally Induced Shoulder Capsulorrhaphy”. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine, July 1998, Vol 6, #3, Saunders and Co., pp 126-130. 23. Levy O, Wilson M, Williams H, Bruguera J. A., Dodenhoff R, Sforza G, and Copeland S: “Thermal capsular shrinkage for shoulder instability: Mid-Term Longitudinal Outcome Study.” J Bone Joint Surg Br, Jul 2001; 83-B: 640 - 645. 24. Thabit, G III, Therapeutic Heat: “A Historical Perspective.” Op Tech Sports Med 1998; 6: 118-119. 25. Wong KL, Getz CL, Yeh GL, Ramsey M, Iannoti JP, Williams Jr GR: “Treatment of Glenohumeral Subluxation Using Electrothermal Capsulorrhaphy Arthroscopy.” The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery August 2005 (Vol. 21, Issue 8, Pages 985-991) 26. Hayashi, K DVM, PhD, Markel, M DVM, PhD: “Thermal Modification of Joint Capsule and Ligamentous Tissues.” Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine, Vol 6, No. 3, July, 1998. 27. Lu, Y MD, Markel, M DVM, PhD, Kalscheur, V, HS, Ciullo, J, BS and Ciullo, J. MD: “Histologic Evaluation of Thermal Capsulorrhaphy of Human Shoulder Joint Capsule with Monopolar Radiofrequency Energy During Short to Long Term Follow-up, Arthroscopy.” The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, Vol 254, No. 2, February, 2008, pp 203-209. 10 28. Fuchs, Bruno, Jost, Bernhard, Gerber, Christian: “Posterior-Inferior Capsular Shift for the Treatment of Recurrent, Voluntary Posterior Subluxation of the Shoulder.” JBJS, Vol 82-A, #1, Jan 2000, pp 16-25 29. Wang Vincent M, Sugalski Matthew T, Levine William N, Pawluk Robert J, Mow Van C, and Bigliani Louis U: “Comparison of Glenohumeral Mechanics Following a Capsular Shift and Anterior Tightening.” J. Bone Joint Surg. Am., Jun 2005; 87: 1312 - 1322. 30. Harvie P, Pollard T. C. B., Chennagiri R. J., and Carr A. J.: “The Use Of Outcome Scores In Surgery Of The Shoulder.” J Bone Joint Surg Br, Feb 2005; 87-B: pp 151-154. 11 List Of Figures Number Fig. 1 – AGE DISTRIBUTION – The patients’ median age at the time of surgery was 53 ± 7 years (range 37 to 71). Twenty-one were men, five were women. Fig. 2 -- PATIENT SATISFACTION FORM Fig. 3 -- SIMPLE SHOULDER TEST FORM Fig. 4 – SHOULDER FUNCTIONS TEST –Fig. 4 - There was significant improvement in the SST score after surgery. Most notable increases in activities were: Sleep comfortably, wash opposite shoulder, lift eight pounds to shoulder level and shoulder comfortable with arm rested at side. Three most common activities that patients could do before surgery were place a coin on a shelf at shoulder level, lift a pint to shoulder and carry 20 pounds at your side, therefore they show the least change post-operatively. Table 1 -- VAS PAIN AND FUNCTION – Table 1 - There was a significant decrease in pain of the shoulder at the follow-up visit. There was also a significant increase in functionality of the shoulder at the time of the follow-up visit. Overall it appears that the procedure was a success with these patients. 12