ASAIB Conference 2014 Garson Royal Engineers~

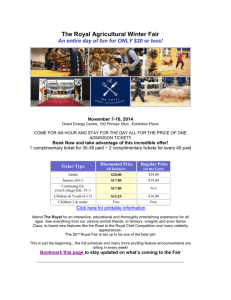

advertisement

The Royal Engineers and their Maps of the Cape Eastern Frontier As some of you here are aware, the University of the Witwatersrand’s collection of Africana is a remarkably fine one and has been described as the jewel in the university’s crown. I was fortunate to have been placed in charge of the collection of antique maps, many of which are objects of great beauty. Among these is the Laidler Collection of manuscript maps and plans of the Eastern Cape frontier during the era of the frontier wars (1822-1870).They were drawn by officers of the Corps of Royal Engineers, and also Sappers and Miners, who worked under the officers. They stood out as unique, within the body of the many printed maps in the whole collection. I have chosen to tell you about them and about the people who created them. When I was asked to compile a carto-bibliography of these intriguing maps I had already been busy with their preservation; some of them are very large, and being manuscript, fairly brittle. Placing them in acid-free plastic covers kept them safe and made them much easier to handle. I was rather apprehensive about how to go about the cataloguing, and my fears were fully justified. Although current cataloguing rules were simple enough to adapt, there were difficult hand-writings to decipher, abbreviations, notes and numbering to contend with, and place-names, tribal names and names of individuals had to be rendered in accordance with modern orthography. What was harder was to determine geographical location, often not made clear, and then to find a historical context for most of the items, also frequently not made clear. Although small, the collection presents in these extraordinary maps and plans, aspects of all the six devastating frontier wars. To do justice to each document it was necessary to provide explanatory notes which required considerable research in some cases. Another quandary was how best to illustrate the catalogue. Although each map was photographed the largest maps could only be represented by selected sections. Sadly these maps were the most striking, especially when it came to their colouring. Here we struck another drawback; there simply was not enough funding to provide for colour. What interested me on close examination of these manuscripts, was how much more connected with them one felt than with a printed map, however beautiful. The skill of the drawing enabled one to see into the fabric of the landscape. Correspondence with Colonel E.E. Peel of the library of the headquarters of the Royal Engineers was most cordial and helpful. In requesting the use of the coat-of-arms of the regiment on the cover of the bibliography, permission was granted, and because no such work had yet been done on the Engineers in South Africa, the ‘usual exorbitant fee’ was waived! It sometimes happens in the professional librarian’s working life that the subject matter of material requiring bibliographical treatment is outside the range of his or her academic 1 experience and training. This project was a case in point. However, delving into a new aspect of librarianship turned out to be richly rewarding. In compiling this complicated catalogue I was greatly helped by the availability of the abundant resources of the library’s special collections and the guidance given by my colleagues and certain members of the academic staff. It was also absorbingly interesting to discover what sort of soldiers the Royal Engineers were and what their significance was for South Africa. Military engineering of one kind or another is probably as old as warfare itself. All kinds of devices were employed by warring factions. An example in point is the fiendish catapult used by the Romans to hurl huge stones at the Jews who had fled to the Roman hilltop fortress Masada, in Israel in 73BC, after which the besieged 400, no longer able to hold out, committed mass suicide. Wartime engineering became a structured activity in England from the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066. Since then the Engineers have given unbroken service to the Crown thus claiming a unique position in the military history of Britain. Royal recognition was given in 1787 with the title of ‘Corps of Royal Engineers’. The final seal of royal approval came in 1832 with permission to bear royal arms and to share with the Royal Artillery the motto ‘Ubique quo fas et Gloria ducunt’ (Everywhere where right and glory lead).It is hard for us to find any glory or even right in the horrible wars of today, in which the Engineers continue to play an important role. For example, most of us will have seen images of bomb and landmine disposal; a difficult and dangerous task. The following statement, attributed to TWJ Connolly, author of the ‘History of the Corps of Royal Sappers and Miners’ 1855, gives a useful picture of the multi- faceted nature of their profession. ‘What is a Sapper? This versatile genius …condensing the whole system of military engineering and all that is useful and practical under one red jacket. He is a man of all work of the army and the public – astronomer, geologist, surveyor, draughtsman, artist, architect, traveller, explorer, antiquary, mechanic, diver, soldier and sailor; ready to do anything or go anywhere… .The end of war for the Royal Engineer may be the end of physical danger, but it is also the start of strenuous labour and great endeavour…. peace has often been more rewarding than war’. The Royal Engineers’ first contact with South Africa came when the Cape was occupied by the British forces in 1795. For the 7 years’ duration of that occupation a small detachment of Royal Engineer officers carried out fortifications, territorial and coastal surveys, utilizing the few and often unreliable maps and plans at their disposal, producing new maps of their own. Many of these are lodged in the Cape Archives, the Public Record Office in London and the British Library, as well as other military repositories in the UK and Commonwealth countries. A good record of their activities during this time, held in the Department of Historical Papers in the Witwatersrand University Library, is a remarkable report on fortifications compiled by a Captain George Bridges. The manuscript is a model of clarity, is written in a beautiful hand and supplies 2 facts and figures, footnotes and references to numbered plates recorded in the Cape Archives, many of which I have seen and much admired. It is interesting to note here that there was a surprising lack of maps and plans that the Engineers could have used as a basis for their own work. The mystery of this strange gap was eventually cleared up in the 1950’s. Cornelis Koeman, an eminent Dutch historian of cartography, discovered a portfolio of hundreds of maps and plans in the Ordnance Survey Department in Delft in the Netherlands. There he found a fine collection of manuscripts made by skilled Dutch surveyors commissioned by Cornelis Jacob van der Graaff, governor of the Cape Colony from 1785 to 1791 and himself a military engineer. On being summoned back to Holland to account for his alleged maladministration of the colony, he took the whole collection back with him, no doubt with malicious intent! Had these maps remained behind for future use locally, the cartography of the Cape might have had a firmer base than was the case in the early years of British occupancy. There is yet another cache of wonderful manuscript maps in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, spirited away by the famous Dutch soldier and scientist and discoverer of the Orange River Robert Jacob Gordon, who travelled all over the colony making maps and magnificent drawings as he went. By the second British occupation in 1806, there was a growing need for the fortification of the eastern frontier against the dispossessed Xhosa. The colony had now entered the era of the frontier wars in which the resources of the Engineers were to be increasingly utilized. The earliest map in this collection of RE manuscripts is dated 1822. By this time the training of the Royal Engineers had been radically improved by the creation in 1812 of additional rigorous training on top of that already received at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. This training centre was established at Chatham in Kent. Here the Engineers and Sappers and Miners (the non-commissioned ranks) were welded into one corps, emerging with all the capabilities described earlier. This was achieved largely due to the influence of the Duke of Wellington, who understood the dangers confronting military engineering and stressed the need for greater sophistication in their training. Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert, also lent his enthusiastic support. A fascinating book on this development gives a picture of a staggeringly demanding curriculum, including a high level of physical fitness, the study of foreign languages, architectural drawing, sinking wells in the desert, mathematics, managing horses, throwing pontoons over rivers and a multitude of other subjects. To judge from the fine detail of their maps and in their writings, acute observation of surroundings was one of the skills acquired in the training that they received. The predominant functions of the cartographic items in this collection were twofold: in the first place maps and plans were used to illustrate official military reports and articles in professional journals and monographs of which the Royal Engineers were prolific writers; secondly the concern would have been to supply accurate information to the cartographers of the day who were producing maps of southern Africa, and who relied on information from a wide variety of sources. Many of the well-known travellers in the colony such as William Burchell, Hinrich 3 Lichtenstein, John Campbell and many others, illustrated their travels with maps which were certainly useful, but the information supplied by the engineers would have been without question the most accurate and workmanlike, based as it was on thorough geodetic principles. Undoubtedly the most significant and lasting feature of the Royal Engineers’ contribution lay in the areas of geodetic survey and topographical mapping. In the gradual development of this field a recurring theme is the frustration experienced by succeeding commanding officers of the narrowness of vision and parsimony of the home government which caused many projects to be either abandoned or hampered, resulting in slow progress in coordinated survey and the compiling of accurate maps. A good example of how their skills were employed, goes back to the arrival of the Abbe Nicolas Louis de la Caille at the Cape in 1751 His work is a large study in itself, but it is enough to say here that his calculations and observations made in the colony provided the groundwork for geodetic and topographical survey; a substantial and scientific basis for a firm foundation. Sadly his work fell into obscurity until Captain George Everest, convalescing in the Cape, and for whom Mount Everest is named. Everest, a surveyor himself, came across de la Caille’s records and minute calculations. He encouraged Sir Thomas Maclear, the Astronomer Royal at the Cape to assess de la Caille’s work, from which a magnificent treatise was produced. In conducting over ten years the revision, 100 years after de la Caille’s arrival, Maclear was ably assisted by the Royal Engineers, acknowledging in the warmest terms the friendship and zealous co-operation of the engineer department. Maclear’s successor, Sir David Gill, in recommending the employment of the Engineers in further geodetic activities, commented on the quality of their work on the completion of the triangulation of the Cape Colony and the Transvaal in 1892. Gill wrote that ‘it is a consistent and accurate basis upon which all future surveys and the subsequent cartography of the country may be confidently founded.’ In spite of this development the governing powers had not seen fit to provide the British forces in the Anglo-Boer war of 1899 to 1902 with adequate maps. It was only after the war that substantial survey was continued under the Royal Engineers who completed the colonial survey of the Orange River colony in 1911. It was said after the completion that ‘the greatest credit is due to the officers and non-commissioned officers … . They never spared themselves nor grudged the hardships incidental to such work,…such prolonged and continual exertions are quite exceptional’. Reference has been made to the Royal Engineers in time of peace. Engagement in non-military matters is an attractive feature of their activities, and specialized training in a variety of disciplines fitted them admirably for civilian duties and scientific and cultural pursuits. They were regular contributors to learned journals in the sciences and the humanities, and many were fellows, members, licentiates and associates of bodies such as the Royal Society, the Royal Geographical Society, the Royal Institute of British Architects to name a few. It is therefore not surprising that the period of the Engineers’ active involvement in South Africa should have yielded some fine examples of works unconnected with warfare. Perhaps the most striking is the design and construction of the Franschoek Pass by Colonel William Cuthbert Holloway, 4 commanding officer from 1818. Of this Lord Charles Somerset said, it was a ‘gratifying instance of the triumph of art over nature, and has no parallel out of Europe, and is indeed to be considered with the Simplon itself.’ An interesting facet of Holloway’s character was his humanity, not only in conceiving the construction of the pass as a way to facilitate communication between inhabitants of the area, but also in his support for the emancipation of slaves at the Cape. Illustrated accounts of soldiers’ experiences in foreign parts are a well-known literary genre. These are by no means the preserve of Royal Engineers, but there are interesting works by them of artistic as well as literary value, demonstrating a keen response to the landscape of the country and its inhabitants, human and animal. Lieutenant Cowper Rose’s ‘Four Years in Southern Africa’, illustrated most beautifully by him, became very popular, although he did little to endear himself to the colonists by his unflattering descriptions of themselves. The book is a sought after item of Africana. Well-known of course is William Cornwallis Harris of the Bombay Engineers. His superbly illustrated works are classics of Africana, rich in detailed observation. An unusual item that I came across, written in 1820, interested me enormously. It is a Report upon Kaffraria in Southern Africa by a young lieutenant, Ives Stocker. It is exceptionally literate, detailed and at times lyrically descriptive of the countryside, indicating a highly developed aesthetic sense and an aptitude for minute description. He was also a magnificent mapmaker and water colourist. He drew a remarkable panorama of Cape Town and surrounds, seemingly from the vantage point of Signal Hill. It is in private hands and I was privileged to be able to see it. Numerous sketches and water colours, designs for furniture, and details of architectural features by other Engineers can be seen in the Cape Archives. I have seen many of them; and have been impressed by their high quality. Several buildings in dressed stone, of Royal Engineer design, notably in Grahamstown and King William’s Town, have been declared national monuments. A well-known landmark, also a national monument, is the Egyptian Building in Cape Town, the first structure of the South African College, built in 1840 and now used by the Fine Arts students of the University of Cape Town. In 1886 the dilapidated military camp in Wynberg was redesigned and constructed by the Engineers. The officers’ mess is a notable feature, not only on account of its fine façade, but also because of the quality of its interior design. The beautifully constructed ceilings, carved panelling, chimney-pieces and cupboards are splendid examples of the Engineers’ talents as designers and craftsmen. Somewhat lesser constructions are a number of elegantly carved tombstones in the King Williams Town cemetery which bear the signatures of the officers who engraved them, presumably to augment an inadequate income. Perhaps it is fitting, in this attempt to present a picture of the Royal Engineer as a well-rounded military figure with skills outside the ordinary, to give the last word to Major Charles Selwyn on his retirement as Commanding Royal Engineer in Grahamstown in 1842: ‘In peace the officer of Engineers is as useful in advancing the arts and sciences and internal improvements of his country, as he is during war…’ 5