A Psychological Model for Tinnitus_SM

advertisement

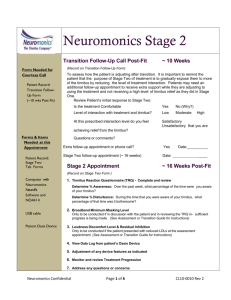

A Psychological Model for Tinnitus Hallam, Rachman and Hinchcliffe (1984, cited in McKenna, 2004) described a relatively radical model for tinnitus for the time, based predominantly on brain activity rather than the traditional cochlear-focused mechanisms (McKenna, 2004). As discussed in Section XXX, tinnitus can occur in the absence of apparent ear pathology. This lends support to the psychological model which suggests that tinnitus is both a psychosomatic and somatopsychic disorder, i.e. both pathways are critical in determining the resultant level of distress experienced by the subject (McKenna, 2004). This theory is consistent with the observation that there does not appear to be a direct correlation between the perceived loudness of tinnitus and the ensuing negative effects experienced by the patient (Baskill and Coles, 1999, Folmer et al., 1999). Attention Filters Further, the model proposes that both CNS and autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity are involved in the manifestation of tinnitus and that it is necessary to consider attention filters, i.e. the ability to process information from only one part of the environment to the exclusion of other parts (McKenna, 2004). Attention filters are commonly described in the world of psychology, although an exact definition seems to be uncertain (Coull, 1998). A quote from William James (1890) is often employed by means of introduction: stating that “everyone knows what attention is: it is the taking possession by the mind in clear and vivid form of one out of what seem several simultaneous objects or trains of thought” (James, 1890 as cited in Coull, 1998). Today, attention is divided into different sub-processes, including ‘attentional orientation’ (directing attention towards a particular stimulus) and ‘selective’ attention (favouring one stimulus over another) (Coull, 1998) difference?. Overall these represent useful concepts from which to consider tinnitus, since presence of tinnitus may not always be perceived as it may not always receive constant attention (McKenna, 2004). Circumstances that may influence the ability to appropriately filter information are likely to impact upon the experience of tinnitus as it has been proposed that selective attention is governed by arousal level (Coull, 1998). For example, when the attention system is overloaded during conditions of high CNS and ANS arousal, tinnitus experience may be enhanced (McKenna, 2004). Factors such as background noises and distractions may mask the tinnitus (Hallam et al., 1984). This model is supported by the observation that many people who experience tinnitus do not report it to be bothersome (Andersson et al., 2005e). Habituation Hallam et al. proposed that the progression of tinnitus is characterised by a process of habituation (a decreased response to a stimulus following repeated presentations), such that as tinnitus persists it gradually loses its ‘novelty’ to the listener (McKenna, 2004). This is a view further supported by anecdotal reports suggesting that tinnitus is not problematic for the vast majority of tinnitus sufferers, and that symptoms of annoyance/distress tend to taper over time (McKenna, 2004). Delayed or failed habituation may arise when there is a high level of ANS arousal, sudden or erratic tinnitus, altered circadian rhythm, impaired neural pathways or where tinnitus acquires emotional significance through a learning process (Andersson et al., 2005e). Figure 1 is presented to describe this process; the process of delayed habituation leads to increased tinnitus and associated distress, whereas by contrast effective habituation results in no distress (Figure 1). Habituation, however, is a controversial issue in tinnitus research, since there is a range of evidence both in favour and potentially opposed to this model (see Section XXX). Incapacitated habituation is proposed to occur in conjunction with inappropriate attention filtering; since an attentional orientation focused on the tinnitus may increase arousal which will in turn limit the attentional filter capability and hinder habituation (McKenna, 2004), providing an unwanted feedback loop as drawn in Figure 1. This model is supported by reports advocating that those who find tinnitus problematic (expressed by ‘complaining’) are more consistently conscious of the tinnitus than those who do not find it bothersome, and further by subjective reports from patients indicating that an improved tolerance is favoured by reduced stress levels (McKenna, 2004). The attentional orientation towards tinnitus is proposed to be heightened in quiet environments, i.e. where the signal to noise ratio is greater (McKenna, 2004), and this is likely to lead to an increased awareness of the tinnitus, and hence may magnify any consequent distress (see figure 1). This theory would be supported by experimental evidence to show that increased distress is experienced by tinnitus sufferers in quiet environments, as in fact has been reported (Stouffer and Tyler, 1990). It is noteworthy, however, that the same study also stated that some individuals reported the exact opposite trend (i.e. a noisy environment exaggerates the tinnitus effects) (Stouffer and Tyler, 1990), somewhat complicating matters, and perhaps highlighting one of the major challenges in tinnitus research whereby the heterogeneity of tinnitus experiences between individuals is enormous. Evidence for the Habituation Model As described earlier, the main evidence for habituation has been summarised in numerous Reviews (e.g. (Coles and Hallam, 1987)) as follows: (1) most people who experience tinnitus do not complain about it, (2) it tends to become less troublesome over time, (3) there is little evidence to demonstrate a correlation between the distress experienced and the perceived loudness (Baskill and Coles, 1999), and (4) subjective reports from many clinics suggest that tinnitus sufferers often acquire tolerance. However, the overall picture is not straightforward, in terms of the reliability of the habituation model. Evidence presented in the literature is, however, conflicting. In one example study, 528 tinnitus patients were assessed by a self-reporting tinnitus questionnaire; 75% of patients found that tinnitus severity did not worsen over time (consistent with habituation) (Stouffer and Tyler, 1990). However, 25% of patients did report that severity had increased since onset (Stouffer and Tyler, 1990). Although not ascertained by the authors, these data suggest either that habituation is an inappropriate model, or alternatively that the process of habituation may have been interrupted. Andersson et al. reports that there is a general opinion that tinnitus becomes less troublesome over time, however, he also states that tinnitus is frequently reported by the elderly population and that at this later stage it found to give rise to particular irritation (Andersson et al., 2005a). McKenna (2004) cited a study by Coles et al., found that most tinnitus subjects in their study sample reported stable and consistent experiences of tinnitus in terms of loudness and annoyance, rather than an increased tolerance (Coles et al., 1988). (The criteria employed to select the sample population and measures of tinnitus assessment are not known to the present author, hence this result may be interpreted with caution). Scott et al. found out from a study of more than 3000 tinnitus patients in Sweden that most reported an increased perceived loudness with increasing duration of the tinnitus, conflicting with the habituation model (Scott et al., 1989). Although, as McKenna (2004) points out, the sample population was taken from a clinical population that actively complained of tinnitus; given the high prevalence of tinnitus it is feasible that a large population may have been in existence for whom an increased tolerance took place, but were excluded from the study because they did not attend the clinic. Overall there have been a number of studies testing the appropriateness of the habituation model for tinnitus by reviewing tinnitus populations (e.g. (Dineen et al., 1997)), or by assessing the physiological response to tinnitus (e.g (Carlsson and Erlandsson, 1991)). Presently it is difficult to draw firm conclusions, since the results are frequently difficult to interpret due to: sample population selection criteria issues, individual variability and the heterogenic properties of tinnitus, and the difficulties of establishing an accurate outcome measure to quantify the degree of tinnitus experienced. In general, tinnitus research has not fully explained exactly how the tinnitus sound becomes troublesome and ‘attention-demanding’ (Andersson et al., 2002). One example theory, however, involves the changing-state hypothesis which claims that ‘auditory stimuli that change state are particularly prone to affect cognitive processing’ (Andersson et al., 2002), and the changing nature of tinnitus stimuli have been proposed to lead to increased distress (Andersson et al., 2005e). Further Limitations The original psychological model set forth by Hallum et al. (1984) does not provide an explicit description of the exact cogitative behavioural processes that they propose to be associated with the detection of tinnitus and the resultant distress; a more detailed model may facilitate the opportunity to test the model in a more rigorous scientific fashion (McKenna, 2004). In fact, the relatively simplistic cognitive behavioural model proposed, centred primarily on the conscious cognitive and behavioural processes, lacks clarity and may require the consideration of additional complexities, such as the subconscious brain processes (as described in the Neurophysiological Model section). In general, experimental evidence available to support/disprove the model seems to be limited; research has predominantly focused on the directly applied clinical question as to the efficacy of the model-based treatments aimed primarily at treating the effects of tinnitus, rather than identifying, defining, and eliminating the root cause (Baguley, 2002, McKenna, 2004). Overall, a more comprehensive and clearly defined psychological model for tinnitus is likely to prove beneficial in terms guiding treatments.