Running head: LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS

advertisement

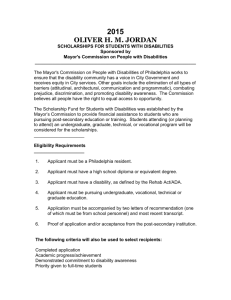

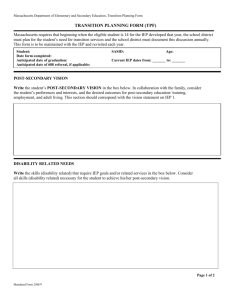

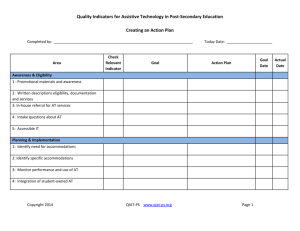

Running head: LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS Literature Review: Learning Disabilities, Remediation, and Success Deborah Davis Liberty University Online EDUC 721: Issues and Trends in Exceptionality Dr. Verlyn Evans July 6, 2014 1 LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 2 Abstract This review seeks to determine if enrollment in remedial English courses impacts graduation completion rates of Learning Disabled (LD) students. The challenge begins with determining who the LD students are. At the post-secondary level, self-identification is the primary method of locating LD students. Many will not self-identify for a variety of reasons. Transitions to college programs can aid students in identifying their needs, as can a variety of tools available. Seeking assistance and making assistance available is the next step. Then, students must identify their own learning strategies and take ownership of their own issues. Programs, such as remedial English courses can aid with learning strategies. This research explores these needs and tools and programs and their impact on graduation rates at a University in rural southern Ohio. LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 3 Learning Disabilities, Remediation, and Success Students with learning disabilities are expected to self-identify at the post-secondary level. Many do. Some do not, and for a variety of reasons. Some believe it is their chance to get beyond whatever constraints they felt held within at prior schooling. Some believe there is a stigma that they do not want to accompany them into college. Some do not realize they must do so. Given that remedial English courses are now required for nearly half of the students entering college, one must wonder if these courses meet the needs of the learning disabled (LD) students who take them. More importantly, one must query if the successful completion of such coursework truly prepared these LD students for the rigors of post-secondary academia, leading to graduation. Reviewing the records of LD students at one such college (Shawnee State University, Portsmouth, Ohio) over the previous ten years, should lead to some answers. Research Question: What is the effect of remedial English courses as measured by graduation completion rates for Learning Disabled (LD) students at a rural four-year-university? Literature Review Identification Issues: “Students with learning disabilities may arrive on college campuses with slightly different characteristics than their peers” (Abreu-Ellis, Elli, & Hayes, 2009, p. 28). While identification of these characteristics may lead to identification of the students as LD, still, those characteristics may go unnoticed for some time. The Learning and Study Strategies Inventory (LASSI) has shown lower scores identify students with LD issues that require special placement or accommodations. While LD issues may relate to some academic genre and not others, to LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 4 provide the best possible environment requires the most possible information. This entire article focuses on timely identification of LDs to ensure proper accommodation and placement. In an area where there is a prominent percentage of non-native English speakers, and a requirement in the schools for English-only learning environments, ELLs are disproportionately and increasingly likely to be identified as LD and place in a special education environment (Sullivan, 2011). Logic would seem to dictate that testing the intelligence of a fish with its ability to climb a tree would be inappropriate. Without language enhancements and interventions, it would seem apparent that testing ELLs in English only will result in lower scores, and consequently higher placements. Students need to be evaluated carefully to determine if LDs are present, or merely language difficulties. One way to aid LD students in reaching their post-secondary goals is through early and appropriate identification of their needs. While the percentage of LD students is increasing in college, the support for disability services is decreasing (Kane, Roy, & Medina, 2013, p. 21). One tool for identification is the Learning Difficulties Assessment (LDA) – an easy to read, nocost, online tool to aid stakeholders in determining areas of strength and weakness, and identifying tools to aid them. Use of the Likert Scale to identify each of the 123 items is then aligned against 23 subsets to post a singular number between one and five with a score of 3.5 or higher indicating a need for further testing and analysis for a Learning Difficulty or an Attention Deficit issue. Using the LDA tool can aid in identification of students needing assistance at the post-secondary level, and therefore effectively allocate the limited disability resources available. Identification is essential in getting these students the services they need to succeed. One program to aid in getting the identification of students with literacy and learning issues is the National Early Literacy Panel (NELP). Recognizing these deficits in elementary LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 5 school through the NELP program has aided students in the services needed through the postsecondary level (Miller & McCardle, 2011). The article on this issue was primarily an argument for the need for greater research in the area of writing in general. However, the suggestion of a synergistic approach to research and resolutions leads to some interesting potential for further analysis. Particularly noteworthy are the elements about the ongoing need for literacy refinement both within and without of the school system. Regardless of learning disabilities, the abilities of the American public to write is sorrowful at best as any reading of a public newspaper will show. Stakeholders Issues: This study indicates that stakeholders of students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are not generally included early enough in the research process to make the research practicable (Dingfelder & Mandell, 2011). Consequently, whatever results are applied can seldom be implemented at the real-world level. Including stakeholders early in the process will enhance real-world applicability to the research, and make it feasible. At the collegiate level, it is crucial that stakeholders be engaged in any changes to the process of remedial English courses – from selection for, through completion of – to make the changes practicable. Zirkel (2013) shows that free appropriate public education (FAPE) is not always the same for each student. Further, students with individual education plans (IEPs) are guided by those instruments rather than the normative standards set by the schools or administrative professionals. Beyond this, parental input has declined significantly in recognition by the court system. As a consequence, remediation at the college level has become less of an exception and more of a standard for any student who graduated with an IEP. At the freshman college level, it LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 6 is now required to teach students to learn, because under their IEPs, they were often only taught to regurgitate knowledge and behave. Perhaps the biggest transition for all students moving into the Post-Secondary environment is the garnering of responsibility for themselves. For LD students, this shift is even more pronounced. Where special educators and parents had previously advocated for the LD students and their rights and needs, the students now must become their own advocates (Garrison-Wade, 2012). This study yielded three basic venues required to aid in LD student success. Self-determination was the biggest factor, those students who want it badly enough will find a way to get what they need. A formalized plan with mentorship and guidance was nearly as important as the students need to know where to go and what to do within their own issues of concern. Postsecondary support was a third big issue in that the decreasing budgets of many schools are restricting available support to developmental services. Within these three elements, the ownership of the issues as belonging to the student is key. All students need to realize they are responsible for their own education. Transition Issues: Daviso, Denney, Baer, and Flexer (2011) studied students in Ohio for their postsecondary plans to learn how transition programs affected learning disabled (LD) students. They found that while many had plans for employment or further education, most were unprepared for the rigor of the requirements for either. A substantial percentage anticipated a requirement to work to afford further schooling. This led to an understanding of how hard it is for LD students to balance these requirements, and explains why many only attend part-time or have extensive delays in their education. This particular study, which took place in Ohio, determined there was a gender difference in direction and desire among LD students, with more males tending toward LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 7 work and females toward further education. In a change from previous studies, this study found that LD students were on or near par with their general education peers with their post-secondary educational plans. This study indicates that students with disabilities who intend to attend post-secondary education are not as prepared as their non-disabled peers (Wilson, Hoffman , & McLaughlin, 2009). They are, however, more prepared than their peers with disabilities who do not plan to attend post-secondary education. One purpose of the study was to determine the viability of transition programs for disability students to post-secondary programs. The resulting consequence is that transition programs can help disability students prepare for post-secondary programs much as they do general education students. However, the post-secondary educational institutions need to be engaged in this process to ensure the functionality of disability educational aids and necessary remediation for students who did not participate in college preparatory programs. Probably the most relevant study to the situation of Shawnee State in the foothills of Appalachia is one published by Irvin, Farmer, Weiss, Meece, Byun, McConnell, & Petrin (2011). This study worked within the rural high school environment, comparing the needs of LD students and their non-LD peers as regarding preparedness for college work. The most telling point of the study was an element referred to as “Academic Self-Concept” (p. 4). Test results show a disparity between student realization of capability and tested scores. Most of the disparity was an indication that LD students could actually do better than they thought they could. Further, those students with very low academic self-concept had difficulty in believing there was value in preparing themselves for post-secondary work as they believed it beyond their capabilities. It is interesting to note that rural students studied also tended to have lower LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 8 aspirations than their urban peers, while the only differing score was in the academic selfconcept. Massengill-Shaw and Disney (2013) explored literacy skills among young adults in postsecondary education programs. The reading clinic used differing methods to meet the needs of the population and provide literacy intervention. A variety of rural, suburban, and urban students were accommodated, largely from middle to lower socio-economic status. These students had completed secondary schooling, though most had required some form of reading intervention in earlier education. The students reading scales, as measured by a variety of standard literacy tests more than doubled, on the average, during the ten week program. Such a program, geared for students with reading challenges, could drastically reduce the number of times remedial English would be required for incoming students, and likely eliminate it for a number of them. When asked what would help them transition from an inclusive high school environment to a successful post-secondary education, students in a study were virtually unanimous in the requirement of two points: mentorship, and self-identification (McNamara, 2011). Through mentorship, learning support, disability services, or other titles, the students had a place and a person to go to for help. Through self-identification, they were given the gateway to the support they needed. Still, many hesitated to self-identify, citing a desire to be identified other than by their disability. Those who failed to self-identify frequently failed at the more stringent requirements, lacking the needed support to succeed. Students in the various programs for LD come up through the school system with a series of Individual Education Plans (IEPs). These IEP lay out goals, sometimes by the week or month, sometimes behavioral, and largely academic. In transition from secondary to post-secondary schooling, however, there is no IEP. There is no set group of people who sit with the LD student LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 9 to determine the next step on the path in detailed minutia. This is where some students get lost in the shuffle (Peterson, Burden, Sedaghat, Gothberg, Kohler, & Coyle, 2013). The authors of this article advice triangulating the goals of the student as the student rises through secondary school Accommodation Issues: In a shift of focus from the students, Dallas, Upton, and Sprong (2014) focused on faculty providing inclusive curriculum to accommodate for the needs of all students. The inclusive method in this article is referred to as Universal Design Instruction (UDI) (p. 12). This study attempted to measure the attitudes of the faculty members toward implementation of UDI within their various course structures. The bottom line in this study was that while most faculty were open to multiple methods to accommodate LD students, those with more training in special education were more forthcoming and had better attitudes toward inclusivity than others. A study by Fichten, Jorgensen, & Havel, et al. (2012), shows that students receiving special education services are more likely to do well both in college and in post-graduate employment situations. In providing accommodations to students within the college environment, the students are taught to cope with their disabilities and better prepared to manage on their own – at the nearly same level as those without disabilities. Those who failed to register and thus received no accommodations struggled both within the college career and in postgraduate employments. Students with disabilities found employment, but not within the field of their studies. The question of “Why?” was not answered in this study but left for further investigation. Once students are registered appropriately, their needs are more likely to be met, whether through remedial English or specific counseling depends on the individual. LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 10 Perhaps half as many LD students enrolled in post-secondary education will graduate as correlated against their non-LD peers (Mytkowski, Goss, & College, 2012). This difference is largely attributed to the difference in LD students who sought aid or accommodation and those who did not. Relationships and conversation with professorial staff were attributed as causal factors for successful LD students. The professors in this study were uniquely trained to provide LD support services. Consequently, the students felt that their responsibility for ownership of their LD issues led to their achievements, and the professors aided the students in their ownership. The understanding of the metacognition issues affiliated with their own LDs allowed these students to grown in their own paths. The study as a whole points to the criticality of LD students being responsible for themselves and their learning. This allows them to seek the support they need and find the tools best suited to them, and is directly related to their success at the post-secondary level. Another key factor in success at the post-secondary level is social skills. Students with any issues within the Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) have these issues identified as part of their diagnostic criteria (DeMatteo, Arter, Sworen-Parise, Fasciana & Paulhammus (2012). In order to provide ASD students with the appropriate accommodations, it is essential to identify what deficits they may have and how best to remediate them. The issue of interfering problem behaviors must be addressed as well. Because of the different methods and modes of intervention for the vast disparity in issues among students with ASD, it is essential that faculty and Special Education staff work closely together to determine the appropriate accommodations for these students. PETERSON LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 11 REED SCHELLY WILGOSH Conclusion All students need support. Students with LDs need to be responsible for seeking their own support if they will be successful. The students who are identified or sel-identify with LDs and pursue the assistance they need are more likely to take ownership of their own issues. Owning their issues leads to better coping strategies and higher success rates. It is likely that this study will validate the literature in this respect. Future studies would include qualitative analysis with LD students to determine the best possible methods of aiding them in identification strategies and erasing any stigma affiliated with the LD community. Transition to college is difficult for most students. Those LD students who are not aided in this transition process will have a harder time still. Tools, such as the Learning Difficulties Assessment (LDA) will allow the students to identify their needs, and when incorporated in the post-secondary program, will aid them in owning their issues and finding learning strategies that work for them individually. LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 12 References Abreu-Ellis, C. Ellis, J., and Hayes, R. (2009). College preparedness and time of learning disability identification. Journal of Developmental Education 32(3), 28-38. Dallas, B., Upton, T., and Sprong, M. (2014). Post-secondary faculty attitudestoward inclusive teaching strategies. Journal of Rehabilitation 80(2), 12-20. Daviso, A., Denney, S. C., Baer, R. M., & Flexer, R. (2011). Postschool goals and transition services for students with learning disabilities. American Secondary Education, 39(2), 77-93. DeMatteo, F., Arter, P., Sworen-Parise, C., Fasciana, M., and Paulhammus, M. (2012). Social skills training for young adults with autism spectrum disorder: Overview and implications for practice. National Teacher Education Journal, 5(4)., 57-65. Dingfelder, H.E. & Mandell, D.S. (2011). Bridging the research-to-practice gap in autism intervention: An application of diffusion of innovation theory. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 41(5), 597-609. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1081-0 Fichten, C. S., Jorgensen, S., Havel, A., Barile, M., Ferraro, V., Landry, M., & . . . Asundion, J. (2012). What happens after graduation? Outcomes, employment, and recommendation of recent junior/community college graduates with and without disabilities. Disability & Rehabilitation, 34(11), 917-924. Doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.626488 Garrison-Wade, D. (2012). Listening to their voices: Factors that inhibitor enhancepostsecondary outcomes for students with disabilities. International Journal of Special Education. 27(2), 113-125. LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 13 Irvin, M., Farmer, T., Weiss, M., Meece, J., Byun, S., McConnell, B., and Petrin, R. (2011). Perceptions of school and aspirations of rural students with learning disabilities and their nondisabled peers. Learning Disabilities Research & Practic. 26(1), 2-14. Kane, S. T., Roy, S., & Medina, S. (2013). Identifying college students at risk for learning disabilities: Evidence for use of the learning difficulties assessment in postsecondary settings. Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 26(1), 21-33. Massengill-ShawD., and Disney, L. (2013). Expanding access, knowledge, and participation for learning disabled adults with low literacy. Journal of Research and Practice for Adult Literacy, Secondary, and Basic Education. 1(3), 148-160. McNamara, C. (2011). Transition for students with special education needs from a mainstream post-primary school in a disadvantaged urban area to the post-school environment: An exploratory case study. REACH Journal of Special Education Needs in Ireland. 25(2), 104-122. Miller, B., and McCardle, P., (2011). Reflections on the need for continued research on writing. Reading & Writing. 24., 121-132. DOI: 10.1007/s11145-010-9267-6. Mytkowicz, P., Goss, D., and College, C., (2012). Students' perceptions of a postsecondary LD/ADHD support program. Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 25(4), 345-361. Peterson, L., BurdenJ., Sedaghat, J., Gothberg, J. Kohler, P., and Coyle, J. (2013). Triangulated IEP transition goals: Developing relevant and genuine annual goals. Council for Exceptional Children: Teaching Exceptional Children, JulAug, 46-57. Reed, M., Kennett, D., Lewis, T., and Lund-Lucas, E., (2011). The relative benefits found for students with and without learning disabilities taking a first-year university preparatory LITERATURE_REVIEW_DAVIS 14 course. Active Learning in Higher Education, 12(2), 133-145. DOI: 10.1177/1469787411402483 Schelly, C., Davies, P., and Spooner, C., (XXXX), Student perceptions of faculty implementation of universal design for learning. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 24(1), 17-30. Sullivan, A. L. (2011). Disproportionality in special education identification and placement of English language learners. Exceptional Children, 77(3), 317-334. Wilson, M. G., Hoffman, A.V., & McLaughlin, M.J. (2009). Preparing youth with disabilities for college: How research can inform transition policy. Focus on Exceptional Children, 41(7), 1-10. Zirkel, P. (2013). Is it time for elevating the standard for FAPE under IDEA?. Exceptional Children, 79(4), 497-508.