Agitation and Aggression in Alzheimer`s Disease: Selective Review

advertisement

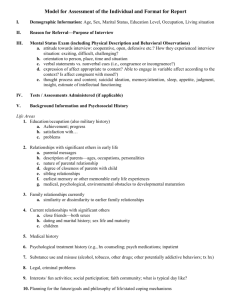

APPENDIX D Agitation and aggression in Alzheimer’s disease: selective review and research priorities David L. Sultzer1, Lon S. Schneider2, Nathan Herrmann3 for the Neuropsychiatric Syndromes Professional Interest Area of ISTAART 1 Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA; and Psychiatry Service, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA 2 Department of Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences, and Department of Neurology, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, and the Leonard Davis School of Gerontology of USC, Los Angeles, CA 3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto and Brain Sciences Program, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center, Toronto, ON 1 Abstract Agitation and aggressive behaviors are among the most distressing symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The etiology, phenomenology, and optimal management of these behaviors are not understood. The term “agitation” is used broadly and inconsistently, although distinct behavioral syndromes probably occur. Several rating scales are used to measure agitated behaviors, yet the scales measure different symptoms in different ways, the construct of agitation is often unclear and the term is inconsistently defined in research studies and clinical practice. Neuroimaging, neuropathology, neurochemistry, and genetic studies suggest that agitation behaviors are fundamental expressions of the neurodegenerative process, and these studies can help reveal specific phenotypes of agitated behavior with shared biological substrate to improve nosology and treatment. Current behavioral and pharmacological interventions for agitation and aggression are insufficiently effective and may carry substantial risk. Attention to four key research areas can improve our understanding and management of agitation in AD: 1) improving the definition and measurement of agitation and aggression, 2) characterizing state and trait biomarkers for distinct symptoms, 3) understanding environmental and caregiver factors that promote or ameliorate agitation, and 4) developing practical, effective, and safe behavioral and medication interventions for specific behavioral syndromes, and identifying patient characteristics associated with maximal effectiveness and safety. 2 delusions, hallucinations, depression, and apathy are cognitive or psychological states with links to traditional psychiatric syndromes, agitation in AD invariably includes prominent and observable behaviors and motor acts, extending beyond an internal psychological state and likely to be more heterogeneous. Finally, agitated behaviors in AD are substantially environmentally dependent. While they often reflect the patient’s internal mental state and include elements of anxiety, fear, misunderstanding, irritability, and impulsivity, the agitated behavior that emerges depends in great part on environmental stimuli and the reactions of others. Thus, understanding the phenomenology of agitated behavior in AD and optimal management approaches must take into account a fluctuating external environment. Introduction Agitation and aggressive behaviors are among the most challenging neuropsychiatric symptoms in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). They are unfortunately common; agitated behaviors occur in about 20% of outpatients with AD and in 40-60% of care home residents. In practice, “agitation” can include a variety of disturbing behaviors. Aggression, a subset of agitated behavior with overt threats, gestures, or violence, is expressed by 10-25% of those with AD. Agitated behaviors are more prominent in those with moderate or severe dementia and tend to persist over the course of AD. Agitation and aggression typically reflect patient distress, and contribute to emergency room visits, acute hospitalizations, long-term institutionalization, and caregiver burden. Aggressive behaviors also compromise safety for the patient, caregivers, and others. Despite the frequency of these symptoms and their contributions to distress and disability, many aspects of the agitation syndrome are not well understood. Available management strategies can be difficult to implement, are modestly effective at best, and can have adverse effects. This paper prepared by the Neuropsychiatric Syndromes Professional Interest Area (NPS-PIA) agitation workgroup provides a brief review of selected issues related to agitation in AD, and proposes a research agenda to improve understanding and develop better treatments. Several definitions of agitation have been offered for clinical and research purposes. Expert conferences have attempted to develop consensus definitions or criteria, with uncertain impact. In clinical settings, the term agitation is used variably and without careful consideration of specific behaviors, which complicates shared understanding. In both clinical and research environments, terms such as “disruptive”, “inappropriate”, or “disturbing” are sometimes used to help define agitation, but these terms are susceptible to subjective interpretation and may reflect the impact of the behavior rather than the behavior itself. The “agitation” that is addressed in an individual research study is defined largely by the items on the rating instrument, rather than a clear a priori definition. Concepts, definitions, and criteria Several factors contribute to the limited understanding of agitated behaviors in AD. Most importantly, the term “agitation” is used broadly to refer to a wide range of behaviors; agitated behavior as viewed by different groups of clinicians or researchers may have nothing more in common than their disturbing nature. Researchers may define agitation for the purpose of an individual study, but the findings apply only to those behaviors measured by the study’s instrument, and results may not be consistent with other research or translatable to clinical care where agitation is defined or measured differently. Second, while symptoms such as Several dimensions of agitated behaviors are apparent and can be used to improve nosology for clinical communication and research study. Examples include: 1) physical agitation vs. verbal behaviors, 2) aggressive vs. nonaggressive behaviors, 3) directed behaviors (e.g., targeted hostility or aggression) vs. less purposeful behaviors (e.g., intense pacing), and 4) context-dependent behaviors (e.g., those that occur during care assistance, such as bathing) vs. generalized behaviors without precipitant. Such dimensions have face validity and are consistent with some research findings. 3 For example, the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) was developed to assess patients in nursing home settings and has three subscales: physically aggressive, physically nonaggressive, and verbal behaviors (1). Principal components analysis of a large sample of CMAI ratings revealed three factors that reflect this construct (aggressive behavior, physically non-aggressive behavior, and verbally agitated behavior), and a fourth factor with hiding and hoarding behaviors (2). others measure symptom severity. NPI ratings are based on caregiver observations, although a variant in development, the NPI-C (10), includes clinician input. Ratings on the NRS, BPRS, and BEHAVE-AD include both clinician and informant observations. Most importantly, how agitated behaviors are defined varies considerably across instruments. For example, the agitation/aggression item on the NPI addresses predominantly resistive or oppositional behaviors, but on some other scales “agitation” is defined as increased motor activity specifically. Thus, the meaning and implications of results using different scales can vary. Principal components analysis of behavioral ratings on several different instruments has shed light on how individual agitated behaviors are related to each other and to other NPS. These findings can help to empirically define phenomenologically distinct syndromes. In an analysis of Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) ratings of AD patients, two components with different dimensions of agitated behavior were apparent: behavioral dyscontrol (euphoria, disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior, and sleep/appetite disturbances) and agitation (agitation/aggression and irritability/lability) (3). Defining agitation syndromes with specific behaviors can provide a coherent and clinically meaningful framework, and can improve classification, assessment, and treatment. Etiology and Neurobiological Underpinnings Structured Assessment A variety of factors affect the expression of agitated behaviors that occur in AD. The cognitive deficits of AD can promote misunderstanding and lead to agitation or aggression. Also, the environment and the individual’s interactions with it contribute to behavior: excessive noise, boredom, or perceived family distress can all raise the likelihood of patient distress and agitation. However, key aspects of the neurodegenerative process itself likely play an independent or important interactive role. Neuropathology in specific cortical regions, altered neurochemistry, and regional cortical dysfunction as seen on neuroimaging are associated with agitated or aggressive behavior. For example, NPI-rated agitation over the course of AD was associated with greater neurofibrillary tangle density in the orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate (11) at autopsy, and aggressive behavior was associated with low choline acetyltransferase level in the superior and middle frontal gyri (12). Neuroimaging studies have explored relationships between regional atrophy, lower neuronal metabolic activity, or specific neuroreceptor binding alterations and the Agitated behaviors can be assessed using instruments that measure a broad range of NPS or those that measure only agitated behaviors. Instruments that are commonly used to measure several NPS include the NPI (4), the BEHAVEAD (5), the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale (6, 7), and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (8). Because agitated behaviors often co-occur with other NPS in AD, the opportunity to explore relationships between agitated behavior and other NPS is valuable. Other instruments, such as the CMAI and the Overt Aggression Scale (9) measure agitation or aggression only. Each instrument measures “agitation” in a different way and interpreting results from different scales can be challenging. Furthermore, instruments may measure change in agitation symptoms in response to treatment differently as well (ref: Ismail et al AJGP Jan 2012). Some assess a broad range of behavioral disturbances, whereas others are focused on particular agitated or aggressive behaviors. Some scales measure symptom frequency and 4 expression of individual agitated behaviors or aggression in AD (13, 14). A recent preliminary report showed that aggressive, hostile, and irritable symptoms in AD, but not impulsive or disinhibited behaviors, were associated with hypometabolism in right frontal/temporal and bilateral cingulate cortex (15). Genetic underpinnings may also play a role. For example, the presence of the long allele of an insertion/deletion polymorphism in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter was associated with both psychosis and aggression in AD (16). Collectively, these studies suggest that individual behaviors are fundamental expressions of the degenerative disorder, and specific neurobiological determinants mediate their expression along with environmental factors. Neuroimaging, neurochemistry, and neuropathology studies may thus help to define biologically specific phenotypes of agitated behavior, which can improve understanding of clinical symptom clusters, their course over time, and treatment based on biological markers. generally modest. Implementing behavioral interventions requires adequate training & monitoring. Some require substantial investments in time, training, and changes to the physical environment. Finally, how best to apply specific interventions to particular patients and behaviors is not always clear. A variety of pharmacological interventions have been used to treat agitated or aggressive behaviors, including antipsychotic, anticonvulsant, serotonergic antidepressant, and antidementia drugs (i.e., cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine). While there have been many clinical trials and clinicians commonly use medications to treat agitated behavior, evidence supporting their efficacy is inconsistent and side effects can be limiting. The majority of trials have studied atypical antipsychotic medications. Meta-analyses of results have shown statistically significant benefit for agitated or aggressive behaviors, although the magnitude of benefit has been small, on average (22, 23). A secondary analysis of the CATIE-AD results suggested that treatment response with antipsychotic drugs may be greater for symptoms such as anger, aggression, and paranoid ideas (24). As with studies of nonpharmacological interventions, the specific behavioral symptoms required for study entry vary across studies and are often not well defined, and several different rating scales and outcome criteria were used. “Agitation” was often defined as a cutoff score on a rating scale, rather than having a clear construct that identifies specific behaviors and their severity required for trial inclusion. Similarly, clinical efficacy was usually defined as an improved score on a rating scale, rather than meeting a benchmark criterion for improved agitation. Most treatment trials lasted 6-12 weeks, and effects of longer-term treatment are unclear. Greater symptomatic efficacy and capture of distinct elements of “agitation” that improve with treatment are critical research goals. Treatment Ideal treatments for agitated/aggressive behaviors in AD are lacking. Two categories of interventions have been considered: behavioral and pharmacological. Behavioral interventions are targeted towards the patient with AD, the caregiver, and/or the environment. Patientcentered approaches include exercise, activities, socialization, or reassurance. Caregiver interventions may include education, support, or developing practical approaches to identify and contain precipitating factors or to extinguish agitated behaviors as they develop. Environmental interventions can address architecture, lighting, or music elements that can ameliorate agitated behaviors. Published treatment guidelines strongly recommend the use of behavioral interventions before or along with any pharmacological intervention. Moreover, several reviews or meta-analyses indicate that some behavioral strategies are effective (17-21). However, in some of the individual studies the target behaviors and outcome measures are not well described, results may vary across studies, and benefits are Medication treatments have adverse effects that can be very serious. Atypical antipsychotic medications can cause sedation, fatigue, extrapyramidal motor changes, urinary symptoms, abnormal gait, edema, and cognitive decline. 5 Short-term atypical antipsychotic treatment in patients with dementia is associated with cerebrovascular adverse events and a 1-2% increased risk of mortality compared to placebo (25). An assessment of the individual patient’s circumstances, including symptom severity, value of modest improvement, vulnerability to adverse effects, and effectiveness of behavioral interventions can help guide appropriate antipsychotic prescription for some patients with marked agitation or aggression. alterations in functional neuronal systems, or genetic risk that, along with environmental and interpersonal factors, mediate individual agitated behaviors. These markers may help to define particular clusters of clinical symptoms with a unitary neurobiological alteration, and thus support the validity of the syndrome. Caregiver and other environmental factors can clearly impact the development, severity, and longitudinal course of agitated behaviors. However, current understanding of these important factors is limited. Better characterization can help identify strategies to prevent agitated behavior or to extinguish prodromal behaviors. Similarly, behavioral interventions to improve agitated behaviors need additional study. Many behavioral approaches are used in clinical settings, often successfully, and many have been tested in clinical trials. However, better understanding of standardized, practical, and relatively simple interventions that foster improvement is needed. Moreover, strategies that can be tailored to individual patients and implemented with modest training, and are consistently effective across community home settings or across skilled care facilities have been elusive. Finally, a reimbursement mechanism for staff training and evidence-based behavioral interventions in care home settings is essential. Research Priorities & Next Steps Several key research issues can be addressed to improve understanding and management of agitated/aggressive behaviors (Table 1) in several areas: improve definition, description, and measurement of agitated behaviors: identify pathophysiological factors contributing to specific behaviors; gain understanding of environmental precipitants and caregiver influences on agitated behaviors, and develop better behavioral or pharmacological treatments. Most importantly, the spectrum of “agitated” behaviors in AD and other cognitive disorders needs to be more carefully catalogued and distinct phenotypes, syndromes and criteria need to be better defined. The validity and longitudinal stability of distinct syndromes, such as aggressive/hostile behavior, excitable/anxious behavior, and excessive motor behavior, require further study. Reliable instruments to measure such syndromes are needed, and should be used in larger samples and in longitudinal studies of AD, mild cognitive impairment, and other cognitive disorders. Better understanding of interactions among these syndromes and their overlaps with other NPS such as psychosis and depressed mood are important. Such relationships are likely different over the stages of dementia and have important implications for clinical understanding and management. Several strategies may help to incrementally improve the benefit/risk equation of medication interventions. Greater efficacy, fewer risks, improved patient function, and reduced caregiver burden are all important goals. Current datasets can be used to identify individual patients or specific behaviors with the most benefit or least harm from the drug intervention. New treatment trials of available or newly emerging drugs that employ carefully selected criteria for agitation and appropriate outcomes are reasonable. In the future, drugs outside the antipsychotic class or novel compounds with targeted antiagitation effects may provide greater benefit or lower risk. Trials that take advantage of more basic research advances in phenomenology and neurobiological markers for distinct agitated Neurobiological factors associated with specific agitation syndromes in AD deserve additional study using neuroimaging, genotyping, or tissuebased techniques to explore regional neuropathology, neuroreceptor changes, 6 syndromes will likely promote development of more efficacious treatments. Targeting novel neuroreceptors or processes, based on improved understanding of agitated behavior in AD, may lead to greater efficacy, and matching particular treatments to distinct behavioral syndromes may substantially enhance clinical benefit. Studies that systematically integrate behavioral and medication interventions, either concurrently or sequentially, would be valuable. Finally, trials of new agents to prevent or treat the neurodegenerative process of AD should include measures of agitation, and longitudinal efforts to treat both the cognitive and behavioral aspects of AD should be better aligned. Overall, research efforts towards agitation and aggression in AD need to address definitions, criteria, and measurement. Additional research to examine course of symptoms, neurobiology, environmental influences, and management can begin with the principles presented here, which can be refined further and translated to testable hypotheses. Key clinical research studies can then be initiated with the attention and support of healthcare systems, national agencies, and advocacy groups. 7 Table 1. Key issues and research priorities regarding agitation and aggression in AD 1. Improve the conceptual framework, definition, and criteria for “agitation” in AD 2. Identify specific behavioral syndromes of agitation and aggression a. Characterize the course of agitated behaviors in AD, relationships with other NPS, and differences across dementia diagnoses 3. Develop instruments to better measure agitation and aggression in cognitive disorders 4. Define the neurobiological underpinnings of distinct agitated behaviors 5. a. Develop biomarkers b. Study biological risks for developing agitated behaviors Develop practical and efficient treatments, both behavioral and pharmacological a. Identify specific agitated behaviors that respond best to treatment b. Use more refined definitions of agitated behaviors in targeted clinical trials c. Evaluate combined behavioral/pharmacological approaches to treatment d. Identify predictors of adverse treatment effects e. Characterize the optimal duration of treatment and predictors for relapse 8 References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. Cohen-Mansfield J: Agitated behaviors in the elderly. II. Preliminary results in the cognitively deteriorated. J Am Geriatr Soc 1986; 34:722-727 Rabinowitz J, Davidson M, De Deyn PP, Katz I, Brodaty H, Cohen-Mansfield J: Factor analysis of the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory in three large samples of nursing home patients with dementia and behavioral disturbance. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 13:991-998 Hollingworth P, Hamshere ML, Moskvina V, Dowzell K, Moore PJ, Foy C, Archer N, Lynch A, Lovestone S, Brayne C, Rubinsztein DC, Lawlor B, Gill M, Owen MJ, Williams J: Four components describe behavioral symptoms in 1,120 individuals with late-onset Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54:1348-1354 Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994; 44:2308-2314 Reisberg B, Borenstein J, Salob SP, Ferris SH, Franssen E, Georgotas A: Behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: phenomenology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48:9-15 Sultzer DL, Levin HS, Mahler ME, High WM, Cummings JL: Assessment of cognitive, psychiatric, and behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia: the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40:549-555 Levin HS, High WM, Goethe KE, Sisson RA, Overall JE, Rhoades HM, Eisenberg HM, Kalisky Z, Gary HE: The Neurobehavioral Rating Scale: assessment of the behavioral sequelae of head injury by the clinician. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1987; 50:183-193 Overall JE, Gorham DR: Introduction - The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24:97-99 Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, Endicott J, Williams D: The Overt Aggression Scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:35-39 deMedeiros K, Robert P, Gauthier S, Stella F, Politis A, Leoutsakos J, Taragano F, Kremer J, Brugnolo A, Porsteinsson AP, Geda YE, Brodaty H, Gazdag G, Cummings J, Lyketsos C: The neuropsychiatric Inventory-Clinician rating scale (NPI-C): reliability and validity of a revised assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2010; 22:984-994 Tekin S, Mega MS, Masterman DM, Chow T, Garakian J, Vinters HV, Cummings JL: Orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex neurofibrillary tangle burden is associated with agitation in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2001; 49:355-361 Minger SL, Esiri MM, McDonald B, Keene J, Carter J, Hope T, Francis PT: Cholinergic deficits contribute to behavioral disturbance in patients with dementia. Neurology 2000; 55:1460-1467 Bruen PD, McGeown WJ, Shanks MF, Venneri A: Neuroanatomical correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2008; 131:2455-2463 Hirono N, Mega MS, Dinov ID, Mishkin F, Cummings JL: Left frontotemporal hypoperfusion is associated with aggression in patients with dementia. Arch Neurol 2000; 57:861-866. 9 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. Sultzer D, Melrose R, Leskin L, Narvaez T, Ando T, Walston A, Harwood DG, Mandelkern MA: FDG-PET cortical metabolic activity associated with distinct “agitation” behaviors in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2011; 7 (Suppl): S744-745. Sweet RA, Pollock BG, Sukonick DL, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, Klunk WE, Kastango KB, DeKosky ST, Ferrell RE: The 5-HTTPR polymorphism confers liability to a combined phenotype of psychotic and aggressive behavior in Alzheimer disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2001; 13:401-409 Kong E-H, Evans LK, Guevara JP: Nonpharmacological intervention for agitation in dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health 2009; 13:512-520 Vernooij-Dassen M, Vasse E, Zuidema S, Cohen-Mansfield J, Moyle W: Psychosocial interventions for dementia patients in long-term care. Int Psychogeriatr 2010; 22:11211128 Ayalon L, Gum AM, Feliciano L, Arean PA: Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients With dementia. Arch Intern med 2006; 166:2182-2188 Cohen-Mansfield J: Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: a review, summary, and critique. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 9:361-381 Livingston G, Johnston K, Katona C, Paton J, Lyketsos CG: Systematic review of psychological approaches to the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1996-2021 Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel P: Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006; 14:190-209 Maher AR, Maglione M, Bagley S, Suttorp M, Hu J-H, Ewing B, Wang Z, Timmer M, Sultzer D, Shekelle PG: Efficacy and comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications for off-label uses in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2011; 306:1359-1369 Sultzer DL, Davis SM, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, Lebowitz BD, Lyketsos CG, Rosenheck RA, Hsiao JK, Lieberman JA, Schneider LS: Clinical symptom responses to atypical antipsychotic medications in Alzheimer's disease: phase 1 outcomes from the CATIE-AD effectiveness trial. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:844-854 Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P: Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA 2005; 294:1934-1943 10