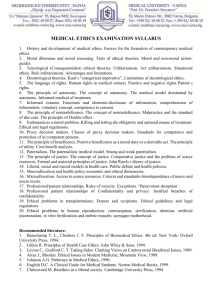

ethics for the safety and health professional: approaches and case

advertisement