Maylam Rhodes Centenary Paper

advertisement

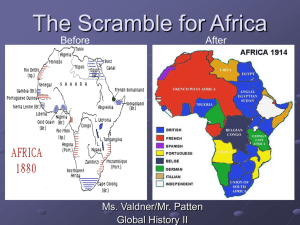

“History at Rhodes, 1911, 1969, 2011 : some random comparative reflections” Paul Maylam Department of History Rhodes University Paper delivered at the Rhodes University History Department Centenary Colloquium 16-17 September 2011 Winnie Maxwell’s inaugural lecture, delivered in 1956, was entitled ‘Random Reflections on the Study of History in South Africa’. So fifty-five years later I also propose to offer some random comparative reflections. It has been said that many novels, especially first novels, are disguised autobiographies. This paper is a not-so-disguised semi-autobiography – about two-thirds of it based on my own experiences in the Rhodes History Department, first as a student in the late 1960s, and second as a staff member for the past twenty years. I am by no means a Foucauldian – certainly not an admirer of Foucault’s historical writing – but I am receptive to some of his ideas and concepts, one or two of which have been helpful in putting this talk together. For instance, he writes about the conditions that make certain kinds of knowledge possible – the conditions enabling various systems of thought to be thought at all. Using the concept of the archaeology of knowledge, he has tried to outline the existence of various systems of thought, making the point that “the history of knowledge can be written only on the basis of what was contemporaneous with it.”1 Foucault goes on to stress the discontinuities and ruptures that characterise the history of knowledge systems over the years. So in this talk I propose to consider the different kinds of historical knowledge that have been taught and transmitted in the history department over the past hundred years – the conditions of possibility, the discontinuities and shifts. It is easy now to be disparaging about the history written and taught a hundred or fifty years ago, but one has to take into account the constraints of the time and the contexts in which historical knowledge was produced and conveyed in the past – such as the limited extent of secondary sources and the narrow focus of that material. So Foucault’s notion of contemporaneity demands that my reflections show some humility and empathy. What possibilities of knowledge were open to W.M. Macmillan when he started teaching history at Rhodes in 1911? What books were available to his students, and what kinds of content, interpretation and ideology could be found in these books? To what extent was he shackled by a particular paradigm or knowledge system? What possibilities of knowledge were open in the late 1960s, and then in the early twenty-first century? What have been the ruptures, shifts and discontinuities between these three moments in the history of history at Rhodes? 1 Michael S. Roth, ”Foucault’s ‘History of the Present’”, History and Theory, 20, 1981, p.36. Page | 1 After arriving at Rhodes (University College) Macmillan was worried that the history syllabus gave too much attention to the history of colonisation. He wanted more British and European history. Aware that this would open him to the charge of eurocentrism, he would later justify his position in his autobiography: “I do not want it to be thought that I wished to force Europe upon Africa, but there was at that time no question of working on African history”2 – the sources were simply not there. Macmillan believed that his most successful course was the one he taught on the Middle Ages: this, he said, “had the most effect in preparing my students for a new view of their own history.”3 Macmillan would in later life make clear why he had this preference for European history: What passed for South African history when I started my teaching career was the tale of the conquest of a new country by lonely and scattered white men, with no regard whatever for the interests or the fate of ... [indigenous people]. History was the triumph of white power in crushing all these peoples.4 This wariness was well justified. Among the prescribed history texts at Rhodes in 1911 were C.P. Lucas’ Historical Geography of the British Colonies, and J.R. Seeley’s The Expansion of England. This is how Lucas viewed this country’s past: “South African history,” he wrote, “consists largely of wars and treaties with Boers and natives.”5 Today a laughable assertion, but stated in all seriousness over a hundred years ago, and the kind of view transmitted to Rhodes history students at the time – such were the extreme limitations on the possibilities of knowledge. All the old stereotypes and howlers are to be found in Lucas: indigenous people readily described as “savages”; Shaka deemed responsible for “wholesale extermination”; the “Transvaal Boers ... held in low estimation”; the eastern Cape eventually becoming “settled and civilised by incomers of British race.”6 Another prescribed text for Rhodes history students a hundred years ago was J.R. Seeley’s Expansion of England, first published in 1883. Seeley’s approach was informed by his own firm sense of Anglo-Saxon superiority, by an unabashed Whig view of history, and by a notion that the proper focus of historians should be on the state. So students would 2 3 4 5 6 W.M. Macmillan, My South African Years (Cape Town, 1975), p.114. Ibid., p.115. Ibid., p.162. C.P. Lucas, Historical Geography of the British Colonies (Oxford, 1900), iv, p.225. Ibid., pp.15, 136, 191, 271. Page | 2 have read that “slowly but surely England has grown greater and greater,”7 and been told more particularly of the country’s “maritime greatness” and its “industrial greatness”.8 All this was very much in keeping with the founding ethos of Rhodes University College, established in 1904 with the clear purpose of extending and strengthening the imperial idea in South Africa, and, as John Darwin has put it, making Rhodes “the engine room of English cultural ascendancy in South Africa.”9 This Whig view of history would have been reinforced by other texts on the 1911 reading list. Books on English constitutional history by Stubbs, and on seventeenth-century England by S.R. Gardiner – both serving to instil in the minds of young students in the colonies that the British constitution, as it had evolved over the centuries, should be the model for any emerging nation. Moving on to the late 1960s, my own student days at Rhodes - what were the limits and possibilities of historical knowledge at this time? What could be taught, given the available literature? For my sins I am an inveterate hoarder of notes and papers – so I still have my third-year lecture notes, bibliographies, and exam papers. Without wishing to embarrass Rodney – in fact, I hope to do the opposite – I will focus on the post-1860 South African course that he taught in 1969. We were given a pretty exhaustive 34-page bibliography, carefully subdivided into sections. There was a section on African societies – nearly all the texts listed here were by anthropologists (Monica Wilson, Isaac Schapera, Eileen Krige, Hilda Kuper) – testimony to the underdeveloped state of African history in South Africa at the time – although the list did include books by D.D.T. Jabavu and J.H. Soga. A student wanting to read about black political opposition in the twentieth century would have had to rely on Eddie Roux’s Time Longer than Rope. The Simons’ Class and Colour only appeared in 1969, and Walshe’s Rise of African Nationalism in 1970. Rodney did, though, have enough material to give informative lectures on twentieth century African resistance – the Bambatha rebellion (Shula Marks’ book was not yet out, but I do remember Shula coming to Rhodes and giving a lecture on the rebellion), the Bulhoek massacre of 1921, and the 1896-97 chimurenga. I recall Rodney giving us copies of 7 8 9 J.R. Seeley, The Expansion of England (London, 1911), p.162. Ibid., pp.95, 100. Paul Maylam, The Cult of Rhodes (Cape Town, 2005), pp.54-65. Page | 3 unpublished papers by Ranger on the Shona-Ndebele uprisings – this, at the time, was the latest work, at the cutting edge. In the field of political economy none of the fresh revisionist work of the 1970s, by Legassick and others, was yet out. I recall Rodney urging us to read one pioneering article – Blainey’s “Lost causes of the Jameson Raid”, offering some kind of materialist analysis of the raid. I remember being stimulated by the article, but the wider historiographical significance of the piece was rather lost on me. I also wrote an essay on the industrial colour bar, following Doxey’s line that the colour bar was a product of white prejudice and market forces. I had a far too unoriginal, uncritical mind to challenge this orthodox view. In my honours year in 1970 I took, among others, the course on seventeenth-century England, by now run by John Benyon – a field of history that had generated a particularly rich literature – a literature which had grown and broadened significantly since 1911. No longer was the focus centred on relations between crown and parliament, as had been the case with Gardiner and others. Now there was the stimulating work of Christopher Hill, who was moving out of his vulgar Marxist phase of the 1940s and into a more nuanced analysis of politics, ideology, religion and popular struggle. It was in this course that I first discovered the Levellers and Diggers, perhaps England’s earliest genuinely democratic movements – discovered through the work of social democrat activists like Eduard Bernstein and H.N. Brailsford. This was a field I enjoyed, and taught for some years in Durban, but have not kept up with during the past twenty years. Looking back over the past forty years or so there is a clear picture of the remarkable expansion and broadening of the discipline of history during those four decades, with the emergence of branches or sub-disciplines that were little known in the 1960s. This is particularly true of South African history. There are now many themes that students can engage with, themes that it would have been very difficult to teach over forty years ago. The historical literature on South Africa has burgeoned – some might say to too great an extent, so much so that there is a crisis of overproduction and underconsumption, with some work being published but read by hardly anybody. I spend a term teaching South Africa in the industrial era to second-year students. I have compiled over the years a lengthy bibliography comprising over 600 items – it could well be five times as long if I were to make it a comprehensive list of published work on Page | 4 South African history since the 1880s. I find that there are only two items on my list that were also on Rodney’s 1969 list – Doxey’s book on the colour bar, and Hunter’s collection of essays on industrialisation and race relations – both there for historiographical reasons. I build up a course of lectures around what I call three ‘I’s – inequality, identity and ideology. Why is South Africa the most unequal country in the world? Why have certain kinds of identity – racial and ethnic – become so ingrained in the South African psyche? What have been the ideologies and practices of domination and opposition? Just take the second of these – ethnicity and nationalism – a theme not on the agenda of historians and social scientists in South Africa forty years ago. Now there is a vast literature on Zulu nationalism, Afrikaner nationalism, and coloured identity, and a growing body of work on English and Indian identities. There is enormous scope to explore other themes and topics. Urban history was hardly developed at all in the 1960s – now it is a vast field. So I can set an essay on District Six or Sophiatown, and direct students to at least ten texts on each; or on gangs on the Rand, for which there is extensive published work. There is gender history (taught by my colleagues, Julie and Carla), environmental history (taught by Alan), the history of health and dis-ease (taught by Carla), film and history (taught by Gary Baines), the history of popular culture (taught by Vashna). I can set essays on the social history of cricket (thanks to Bruce Murray), or rugby. And so it goes on. So far I have stressed the discontinuities – centred on the changing nature and broadening scope of the discipline, and how these shifts have impacted on the content of courses offered in the department. It is, though, also important to highlight the continuities in the practice of the History Department. I will mention four. First, there has always been a firm commitment and dedication to undergraduate teaching. This was Winnie Maxwell’s central focus and major concern. I am sure that many benefited from this careful, sometimes brusque, attention and nurturing – I certainly did – Winnie and her colleagues making something of a historian out of not very promising material. Such was her influence and impact that there was a time in the 1980s when the chairs of history at Wits, UCT, Durban, Pietermaritzburg and Rhodes were all held by her former students. And Rodney maintained this emphasis. He has remarked on the attention paid to detail in the teaching of undergraduates, and how the department “spent Page | 5 quite a lot of [its] time ... turning third-class minds into second-class results, or seconds into firsts.”10 I believe, too, that we have continued this tradition over the past twenty years. My colleague, Julian, in particular has dedicated himself to first-year teaching for the past ten years – with remarkable results which have benefited the department as a whole. During the crisis years of the late 1990s we had a total of just over 100 students in the department, and we feared for the future. After Julian introduced his now famous History 102 course our numbers shot up – about 400 registering for 102 alone in 2001. For myself I can say that the richest rewards and greatest gratification that I have gained in my time here have come from the many wonderful undergraduates I have taught – some of whom are here today – more gratifying than any of the publications I have put out. My second point is that the department has consistently leant more in an empirical direction than a theoretical one – not that one can take theory out of history – there are always premises, assumptions underlying any historical work, even if they are more implicit than explicit. In his autobiography W.M. Macmillan admitted that he never developed a capacity for abstract reasoning,11 and as a sharp observer his method was clearly more inductive than deductive. This, too, was Michael Roberts’ approach. And Rodney shared Winnie Maxwell’s “very, very strong insistence on not reaching historical conclusions without producing the evidence.”12 This, too, has generally been my approach. I consider myself to be a soft materialist, but like my predecessors I prefer to work inductively rather than deductively – which has sometimes got me into trouble on the Higher Degrees Committee where social scientists complain that history thesis proposals are inadequately theorised. Third – interdisciplinarity. History is, of course an inherently interdisciplinary subject, involving as it does the study of every dimension of the human experience. Macmillan was appointed in 1911 as a lecturer not just in history, but also in economics. And much of his research, particularly in the eastern Cape, fell into the realms of sociology and economics. The courses, we now offer, and the research interests pursued in the department, link up with many other fields – political economy, ecology, psychology, medicine, film, literature, and cultural studies. And looking around this room I can see people trained as historians 10 11 12 “Interview with T.R.H. Davenport”, by Nicholas Southey, South African Historical Journal, 26, 1992, p.26. Macmillan, My South African Years, p.24. “Interview with T.R.H. Davenport”, p.23. Page | 6 who have moved across disciplinary boundaries – into education, sociology, development studies, health research, and statistics. My last point concerns the link between the past and the present. In her eulogy at Macmillan’s funeral in 1974, Lucy Sutherland stated that Macmillan used “all his powers of historical imagination to recreate the past, relate it to the present, and apply it as a guide for the future.”13 I like to think that this is still our approach in the department. We hope that through the study of history our students will make better sense of the world we live in today, and be better equipped to cope with what threatens to be a difficult future. Our assumption is that one cannot properly understand any present-day issues – whether it be the global financial crisis, rising militarism, environmental decay, terrorism, gangsterism – without looking at these phenomena historically. So, yes, we tend not to teach history ‘for its own sake’, and we have something of a presentist agenda which is much disliked by many historians. It is significant that most of our best students of the past ten years have not become historians, but have become involved in contemporary issues – land reform, farm labour, HIV/AIDS, water provision, and other development-related concerns. In some ways I regret that we are not training a new generation of historians, but I have enormous admiration for these students’ commitment to addressing contemporary issues in South Africa. Some final words. I have spent over a third of my life associated with this department – four years as a student, twenty years as a member of staff. My life has been much enriched by this association. The greatest surge in my own personal development came in my student days here. For the past twenty years I have found the department, the university and the town – with all their shortcomings – to have provided a wonderful working environment. When Winnie Maxwell retired at the end of 1974 she said “This has always been a good department and I have merely built onto sound foundations.”14 Having inherited from Rodney a good department built on solid foundations, I would like to be able to say the same when I retire at the end of next year. 13 14 Foreword to My South African Years, p.vii. J.A. Benyon, C.W. Cook, T.R.H. Davenport, K.S. Hunt, “Winifred Maxwell, Historian”, in J.A. Benyon et al (eds), Studies in Local History: Essays in Honour of Professor Winifred Maxwell (Cape Town, 1976). Page | 7