Chapter 2 - Biography and the Sociological Imagination

advertisement

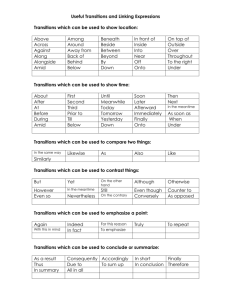

Chapter 2 – Shanahan and Macmillan The Life Course as a Paradigm p. 46 bottom – “This chapter provides further detail about the life course, exploring many of the principles, mechanisms and concepts that together constitute the life course as a paradigm. The overarching goal of any paradigm is to create a new way of looking at things and to provide basic tools with which the imagination can work.” Principles of the Life Course *note – p. 47 middle - “all but the first principle discussed below have a special status as linking mechanisms: they identify processes by which transitions and behavioral development are interrelated.” p. 48 - “Principles of the life course paradigm help us think about how such changes and the transitions they precipitate affect people’s lives.” Principle #1 – p. 48 – Historical Time and Place - the life course takes on different patterns in different historical times and geographic places. - Example – each graduating class encounters a different labor market, characterized by a unique level of opportunity and unique forms of employment. Principle #2 – p. 49 – Situational Imperatives - the importance of situational imperatives, which refer to the demands or requirements of a new situation - Example – the more demanding the situation, the more individual behavior is constrained to meet role expectations – the boys growing up during the great depression who were called upon to meet the economic and labor needs of their hardpressed families. o These boys turned out to be quite successful and experienced something like adult status that served them well in the work world and gave them self assurance in their work careers Principle #3 – p. 50 – Linked Lives - the effects of social change on a person’s life greatly depend on his or her network of interpersonal relationships, including, for example, immediate and extended family members, mentors, and close friends. 1 Principle #4 – p. 51 – Agency - Through the exercise of agency, people construct their own life course through their actions, reactions, and choices. - Overarching point – people are purposive – they act based on past experience and what they have learned from it People strive to maintain a sense of control over their biography Principle #5 – p. 52 – Life-Stage – the meaning and consequences of events depend on when they occur in a person’s life - Acknowledges that, without locating people with respect to their age and with respect to history, the life course cannot be understood in its full complexity It is not chronological age per se but rather “social age” and “social timing” that determine the significance of historical change and social context Principle #6 – p. 54 – Accentuation – when transition heightens a prominent attribute that people bring to the new role or situation, we refer to the changes as an accentuation effect - Relates transitional experiences to the individual’s life history of past events, acquired dispositions, and meanings Behavioral patterns before transition are magnified with social change p. 54 - “These principles – summarized in Table 2.1 (p. 55) – represent conceptual tools that help understand the connections among individual lives, developmental trajectories, and the changing social world.” These principles are useful for helping understand all kinds of transitions in the life course, not just large scale historical or social transitions. For example, they are useful in helping us understand transitions from adolescence to young adulthood; losing a job; serious illness; etc. All six principles are working in concert to help us understand biography p. 56 – read – “in other words, the many factors that shape a biography operate in concert. Imagine for a moment that your family has just lost everything but the house or apartment that you live in. What would life be like?” - The answer is likely to be different for each person because the six principles combine in different ways for different people and different families 2 - The principles allow us to study these differences in a systematic way - P. 59 – because each life reflects the workings of the principles of the life course, each life is recognizable as human experience. And yet, because the principles come together in untold diversity, every life is different. Shanahan and Macmillan caution us against making the same error as Erikson – - Ontogenetic fallacy – p. 63 – refers to attempts to explain lives by referring to assumed, inherent properties of people at the expense of a thoroughly social explanation.” o A life course view resists the common temptation to explain someone’s life by saying “that’s the way people are” and presses the inquiry by asking how the social context has shaped the life story.” o P. 66 – “To avoid the ontogenetic fallacy, the analyst must ask what it is about the person’s setting that helps account for their experiences and behavior.” Useful Concepts in Life Course Studies These concepts provide ways of viewing or thinking about social context through time All of these concepts are defined and demonstrated with examples in Table 2.2 on p. 86 Social Pathways – p. 66 – refer to likely sequences of social positions within and between organizations and institutions. - Examples include – progressing through the grade levels of the school system, tracking within schools, leaving the school system and starting a new job, and then conducting one’s career within a company and between companies. - They are: o Contextual – because the refer to sets of positions within a system o Dynamic – because they refer to movement through the positions o Have specified time boundaries – maturity for voting or marriage o Age-graded – on-time and late transitions o Structure the direction that people’s lives can take – produce or constrain opportunities o Multi-level phenomena – p. 68 top – read – “…people work out their life course in terms of established or institutionalized pathways. At the macro end of this multilevel system, pathways are generally established by governments. At the lower levels, the terms may be set by institutional sectors (e.g., 3 economy or education), by local communities, school systems, labor markets, and neighborhoods. Each level of the system, from macro to micro, socially regulates the decision and action processes of the life course, producing areas of coordination as well as discord and contradiction (e.g., laws governing marriage, divorce, and adoption). At the level of the individual actor, some decision pressures and constraints are linked to federal regulation, some to the social regulations of an employer, and some to state and community legislation.” Cumulative Processes – p. 71 – reflect long term patterns of experiences - Can explain why childhood experiences matter for adulthood – at the same time, care must be taken not to overestimate the effects of childhood experiences on adult behaviors - Cumulation associated with duration – p. 71 – long periods of time spent in a given social role – student, worker, spouse, parent – tend to increase behavioral continuity through acquired obligations, investments, and habits. - Cumulation associated with a sequence – p. 74 – “many cumulative processes refer not to the duration of a particular social circumstance, but rather to the triggering of chains of interrelated events (or sequences), which in turn, have significant implications for later well-being and attainment.” o P. 75 – “antisocial youth tend to affiliate with other problem youth, and their interaction generally accentuates their behavior, producing over time what might be described as cumulative disadvantages.” - Cumulative Continuity – p. 75 – o P. 75 Dupre’s research – 2/3rds down the page – read – “The basic idea is that people with higher education will shape their environments…” o the cumulation of experiences tend to maintain and promote the same behavioral outcome - Reciprocal Continuity – p. 76 – refers to a continuous interchange between person and environment in which action is followed by reaction and then by another cycle of action and reaction. o the cumulation of experiences tend to maintain and promote the same behavioral outcome o example – ill-tempered child provokes parental anger/withdrawal, which aggravates child’s outburst; aggressive children generally expect others to be 4 hostile and thus behave in ways that elicit hostility, confirming their initial suspicions and reinforcing their behavior. Trajectory – p. 78 – provide a dynamic view of behavior and achievements, typically over a substantial part of the life span. - A life course trajectory does not prejudge the direction, degree, or rate of change in its course - Developmental Trajectory – p. 79 – refers to change and constancy in the same behavior or disposition over time, not consistency of measurement may be difficult to achieve in many cases o Antisocial behavior from childhood to adolescence – different behaviors indicate antisocial behavior (childhood – biting; adolescence – lying; young adulthood substance abuse) but an antisocial trajectory just the same - Synchronization – p. 80 – temporal coordination of two or more trajectories or roles o we are often on multiple trajectories simultaneously and need to coordinate them Transition – p. 78 – combining a role exit and entry, is embedded in a trajectory that gives it specific form and meaning (example – work transitions are core elements of a work trajectory) - - p. 80 – the meaning of transition has much to do with its timing in a trajectory p. 81 – bottom – life transitions can be thought of as a succession of mini-transitions or choice points p. 81 – early transitions can have lifelong implications because of behavioral consequences that set in motion cumulative advantages and disadvantages o the quality of transition experiences early in life may foretell the likelihood of successful and unsuccessful adaptation to later transitions across the life course p. 82 – “transitions have both an institutionalized and a personal, idiosyncratic nature. In many cases, life transitions are at once an institutionalized status passage in the life course of birth cohorts and a personalized transition for individuals with a distinctive life history.” Turning Point – p. 82 – dramatic change in both the internal and the external aspects of the life course 5 - allow for new opportunities and behavior patterns Shanahan and Macmillan on all the principles and concepts presented in Chapter 2 – p. 85 – “The implication is clear: people’s lives cannot be fully understood by focusing on one point in time or by neglecting their context. Rather, their social settings and their patterns of adjustment and behavior have dynamic qualities and it is these dynamic qualities that determine their meaning. Students should be able to apply these principles and concepts to their own stories. Keep this in mind for your biographies assignment due at the end of the semester. - Tip - Re-read how the authors applied the principles and concepts to Darwin’s biography on pp. 91-100 for ideas of how you might be able to do this for your own story. 6