supplemental demographic information

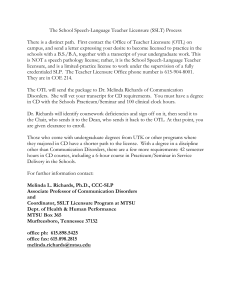

advertisement