H1 The origins of language

advertisement

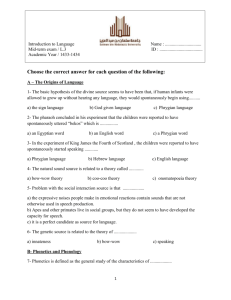

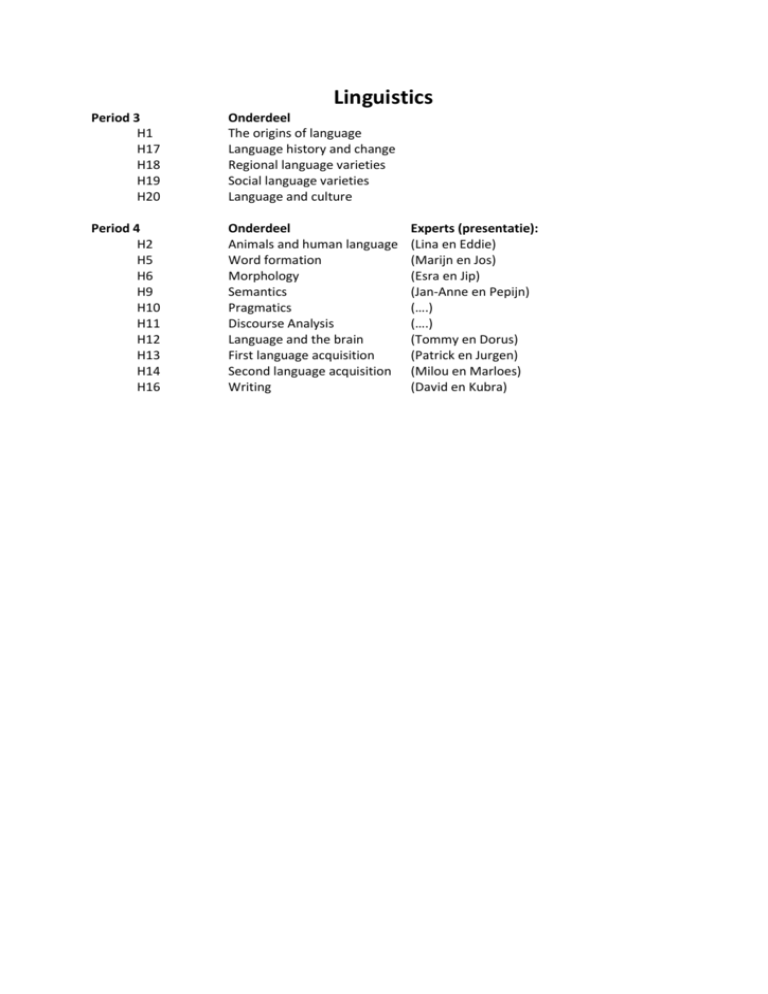

Linguistics Period 3 H1 H17 H18 H19 H20 Onderdeel The origins of language Language history and change Regional language varieties Social language varieties Language and culture Period 4 H2 H5 H6 H9 H10 H11 H12 H13 H14 H16 Onderdeel Animals and human language Word formation Morphology Semantics Pragmatics Discourse Analysis Language and the brain First language acquisition Second language acquisition Writing Experts (presentatie): (Lina en Eddie) (Marijn en Jos) (Esra en Jip) (Jan-Anne en Pepijn) (….) (….) (Tommy en Dorus) (Patrick en Jurgen) (Milou en Marloes) (David en Kubra) H1 The origins of language Different sources: 1. The divine source Without hearing any language around them, they would spontaneously begin using the original God-given language. 2. The natural sound source Imitate the sounds around you: Buzz, hiss, bang ‘’bow-wow theory’’/ Onomatopeia. Lyra bird. 3. The social interaction source ‘’yo-he-ho’’ theory. Sound of a person involved in physical effort: grunts, groans, curses. 4. The physical adaption source The ability to speak. Animals can’t speak because of their physiques. Because we started to walk on 2 feet, we gained the ability to speak. 5. The tool-making source 6. The genetic source Development of the brain. Baby can’t speak but later the brain develops in a way that the baby can talk. Preknowledge 55 BC 55 BC-140 AD 140-787 AD 787-1066 1066+ Pre roman Roman Anglo saxon Viking Norman Conquest (battle of Hastings) Romans brought: - Military - Infrastructure - Language (latin) - Religion Anglo saxon brought: - Seven kingdoms Vikins brought: - Politics and culture - Linguistically Norman invasion brought: - French language / politics - Politicians spoke English to communicate with the people Etymology: historical development of words which is part of historical linguistics Illogicality of spelling: ghoti fish 1476 printing press. Phonology: sound of a language Phonetics: speech Sentences are structured string on words Linguistics is the science of language. History, acquisition, structure. H17 Language history and changes Philology: the study of language history and change. There is a common ancestor for many languages, called Proto-Indo- European. Cognates: a cognate of a word in one language is a word in another language that has a similar form and is or was used with a similar meaning. Example: mutter- mother- madre. Comparative reconstruction: reconstruct what must have been the original (“proto”) form in the common ancestral language. - Final vowels often disappear. Vino- vin - Voiceless sounds become voiced, typically between vowels. Muta- muda - Stops become fricatives. Ripa – riva - Consonants become voiceless at the end of words. Rizu- ris. History of English Pre- Roman/ Pre- Historial. Roman occupation (Latin influences) Anglo Saxon period (beginning of English) Viking Invasions Norman conquest (1066) Celtic + Latin+ Germanic + French = English! Old English is different from Middle English, for both ears and eyes. Old English: calf, deer, ox, pig French influence: beef, bacon, veal, venison. This was because the upper class were the only ones who could afford to actually eat the animal External change: influences from the outside (borrowed words from e.g. Norman French/ Old Norse) Internal change: not caused by outside factors; but within the development of English. Some examples of internal changes: Sound changes. Some sounds simply disappeared from the pronunciation of certain words. (like in knee) Metathesis involves a reversal in position of two sounds in a word. (bridd>bird) Another type of sound change, epenthesis, involves the addition of a sound to the middle of a word. (spinel> spindle) There is also something called prothesis: the addition of a sound to the beginning of a word. Typical in e.g. Spanish. (schola>escuela) Syntactic changes: Change in word order, but also the use of a double negative in Old English. The most sweeping change in the form of English sentences was the loss of a large number of inflectional affixes. Semantic changes: A large number of borrowed word has entered the language while others became out of use. Other processes: broadening and narrowing of meaning. Example of broadening: holy day > holiday. Example of narrowing: hund> hound (only 1 type of breed) Diachronical view: from the historical perspective of change through time. Synchronical view: in terms of differences within one language in different places and among different groups at the same time. Ch. 18 Language and regional variation Difference between dialect and accent: Accent is the way the language is pronounced Dialect also has different words and expressions. NORMS= non- mobile, older, rural, male speakers. Isogloss: a line that represents a boundary between areas with regard to a particular linguistic item. Dialect boundary: when a number of isoglosses come together, a more solid line can be drawn. Dialect continuum: there are no distinct boundaries between dialects. Difference between bilingual and bidialectal. In diglossia, there is a ‘low’ variety, acquired locally and used for everyday affairs, and a ‘high’ or special variety, learned in school and used for important matters. This exists in e.g. Arabic speaking countries. Pidgin: a variety of a language that developed for some practical purpose, such a trading, among groups of people who had contact but didn’t know each other’s languages. no native speakers. A Pidgin is described as an ‘English pidgin’ if English is the lexifier language. When a pidgin develops beyond its role and becomes the first language of a social community, it is called a creole. The separate vocabulary elements of a pidgin can become grammatical elements in a creole. The development from pidgin to creole is called creolization. A number of speakers now tend to use fewer creole forms and structures (they’re using a higher variety of language): decreolization. Between those two extremes may be a range of slightly different varieties. This is called the post- creole continuum. Ch. 19 Language and social variation A speech community is a group with the same dialect and social speech. Social dialects: social class is used to define groups of speakers as having something in common. The two main groups are middle class and upper- class. A social dialect is also called a sociolect. We treat the class as the social variable and the pronunciation or word as the linguistic variable. An idiolect is your personal dialect. We generally tend to sound like others with whom we share similar educational backgrounds/ occupations. Social markers: having a feature occur frequently in your speech (or not) marks you as a member of a particular social group. Examples: post vocalic r, h- dropping, pronouncing –ing as –in. Speech style: basic distinction between informal and formal speech styles. (Whether or not you pay attention to how you’re speaking) A chance from one to the other by an individual is called style- shifting. Overt prestige: when you’re talking to someone of a higher social group or in a formal situation. Cover prestige: used in an informal situation or when the speaker wants to make clear that he’s not the same as the person he’s talking to. Variation in speech style is also influenced by the perception of listeners: speech accommodation. Convergence: attempts to reduce social distance Divergence: used to emphasize social distance between speakers. Another influence on speech style that is tied to social identity derives from register. A register is a conventional way of using language that is appropriate in a specific context. A jargon is special technical vocabulary associated with a specific area of work or interest. Slang (or colloquial speech) describes words or phrases that are used instead of more everyday terms among younger speakers and other groups with special interests. Taboo terms are words and phrases that people avoid for reasons related to religion, politeness and prohibited behaviour. Often: swear words. Vernacular (English): a general expression for a kind of social dialect, typically spoken by a lower status group, which is treated as ‘non- standard’ because of marked differences from the official language users. Ch. 20 Language and culture Culture: refer to all the ideas and assumptions about the nature of things and people that we learn when we become members of social groups. A category is a group with certain features in common and we can think of the vocabulary we learn as an inherited set of category labels. A lexicalized concept is a concept that is expressed in one single word. This is different in all kinds of cultures. The structure of our language, with its predetermined categories, must have an influence on how we perceive the world. (Linguistic relativity) Linguistic determinism: language determines thought. We can only think in the categories provided by our language. The Sapir- Whorf hypothesis: the languages of the Native Americans led them to view the world differently from those who spoke European languages. In their grammar, there is a difference between animate and inanimate entities. As a way of analyzing cognition (how people think), we can look at language structures for clues, not for causes. Example: the Hopi and their belief in animate and inanimate. Classifiers: grammatical markers that indicate the type or ‘class’ of noun involved. The closest English gets to this: there is a distinction between non countable and countable nouns. Social categories: categories of social organization that we can use to say how we are connected or related to others. Example: uncle isn’t necessarily only your father’s (or mother’s) brother. Address terms: a word or phrase for the person being talked or written to claiming kind of closeness. Example: Brother, can you... In many languages, there is a choice between pronouns used for addressees who are close or distant. This is called the T/V distinction. Gendered words: there can be differences between the words used by men and women in a variety of languages. There are examples which show that the female form is seen as ‘special additions’, like in hero- heroine. Gendered speech: women have a higher pitch than men. Women: rising intonation, use of tag questions, back channels. H2 Animals and Human language Can Animals communicate with humans? 2 forms of signals - Informative signals: unintentional (body language) - Communicative signals: intentional (voice) Property of human language Reflexivity Think and talk about the language and reflect on it. We are also the only specie who reflects on their own actions by using language. Displacement We can talk about the present, past and future. Animals can only ‘’talk’’ about the present; when dogs are barking, they bark because something is happening right now. Arbitrariness We just named it an apple. There is no connection between the word and the form of it. It is an onometpetic word. Productivity Create new expressions Cultural transmission Language knowledge is passed on to the next generation. We have to learn a language to speak a mother tongue. An animal doesn’t have to. A cat says instinctively ‘mauw’. Duality (double articulation) We can change a word and give it another meaning. For example, though and through. A dog won’t say foew instead of woef. Talking to animals Do they understand the meaning? No! They respond to the sound of the word. Chimpanzees and language: - Gua: - Viki: was raised like a kid, said something like ‘’mom’’ and ‘’dad’’ - Washoe: they taught her sign language. Took her 3,5 years to learn it. Later, she started to combine the words and make sentences. - Sarah: They used plastic shapes to express a certain action or object. So when we were talking about hugging, she would crab a red cube. - Lana: Used symbols on the computer to express something. For example, a symbol of a banana means ‘food’. Controversy: understanding the language H5 Word formation Etymology The study of the origin of a word Coinage Invention of new words, the most typical sources are invented trade names for products For example, aspirin, Vaseline, Kleenex Eponyms Words that are based on the name of a person or place. For example, Sandwich, jeans, Watt Borrowing Taking over the words from other languages. For example, piano (Italian), pretzel (german), croissant (French). Loan-translation/calque There is a direct translation of the elements of a word into the borrowing language. For example, skyscraper (Engels), wolken krabber (Dutch) or Wolkenkratzer (german). Compounding Combining 2 separate words to produce one word. For example, bookcase, doorknob, fingerprint. Blending Also combining 2 separate words to produce one new term but in blending we take the first few letters from one word en the last letters of the other word. For example, smoke and fog; smog, breakfast and lunch; brunch. Clipping When a word becomes shorter. For example, cabriolet; cab, advertisement; ad, permanent; perm Backformation When a noun (for example) is reduced to form a word of another type, for example, a verb. For example, donate; donation, babysit; babysitter Conversion When a noun is used as a verb. For example, bottle; bottled, butter; buttered. Acronyms New words are formed from the initial letters of a set of other words. For example, CD; compact disk, NATO, NASA, pin; personal identification number Derivation When we add affixes (prefix, infix and suffix). For example, disrespectful, absogoddamlutely H6 Morphology Morphology: the study that investigates the basic forms in language. The elements in a word are called morphemes: such as –s, -ed, -ing. Units of grammatical function include forms used to indicate past tense, or plural for example. Morpheme is a minimal unit of meaning or grammatical function. There are two types of morphemes: Free and bound morphemes. Free morphemes: can stand by themselves as single words. Bound morphemes: cannot stand alone and are typically attached to another form. Stems: the basic word 2 kinds of free morphemes: Lexical morphemes: free morpheme that carries the ‘content’ of the message they convey; ordinary nouns, verbs and adjectives. We can add new ones quite easily, that’s why lexical morphemes are considered a ‘open’ class of words. Functional morphemes: the functional words in a language such as conjunctions, prepositions, articles and pronouns. We almost never add new functional words, that’s why these morphemes are described as a ‘closed’ class of words. 2 kinds of bound morphemes: Derivational morphemes: bound morphemes that are used to create new words or to make words of a different grammatical category from the stem. Example: -ness, -ful. Inflectional morphemes: bound morphemes that are used to indicate aspects of the grammatical function in a word: show whether it’s singular or plural, past tense or not, comparative/superlative, possessive. –‘s (possessive) (also: - s’) –s (plural) –s (third person singular) –ing (present participle) –ed (past tense) –en (past participle) (also: -ed) –est (superlative) –er (comparative) An inflectional morpheme never changes the grammatical category of a word. A derivational morpheme can change the category of a word: when adding the suffix –er, teach becomes teacher. See page 66 for a chart with all the different types of morphemes. Question that might be in the test! The child’s wildness shocked the teachers The child ‘s functional lexical inflectional ness shock –ed derivational inflectional derivational Teach –er –s lexical derivational Inflectional wildlexical the inflectional Morphs and allomorphs: morphs are the actual forms used to realize morphemes. Example, the form cars consists of two morphs, car + s, realizing a lexical morpheme and an inflectional morpheme. (read p. 67) In other languages, different patterns occur to realize the basic types of morphemes Kanuri they use the prefix ‘’nem’’, to make a adjective into a noun Karite (excellent) nemkarite (excellence) Ganda use the prefix omu/aba to show when something is singular or plural Omusawo (doctor) abasawo (doctors) Ilocano copies the first part of the word to make it plural. Úlo (head) ulúlo (heads) Dálan (road) daldálan (roads) Tagalog Copies the first part of the word to change it to future tense Basa (read) babasa (will read) Tawag (call) tatawag (will call) Copies the first letter of the word + -um to make it sound like a command Basa (read) bumbasa (read!) Tawag (call) tumtawag (call!) H9 Semantics Semantics deals with the conventional meaning conveyed by the use of words, phrases and sentences of a language. There are two types of meanings: Conceptual meaning: covers basic, essential components of meaning that are conveyed by the literal use of a word. Example: needle= thin, sharp instrument. Associative meaning: different people might have different associations or connotations attached to a word like needle. These types of associations are not treated as part of the word’s conceptual meaning. Semantic features: sentences can be syntactically good, but semantically odd. The hamburger ate the boy is written acceptable, but the sentence doesn’t make any sense. There are some crucial features of the meanings of a set of words: animate, human, female, adult. (I know this is a bit vague, look at p. 101... It’s not that hard!) There are some semantic roles for noun phrases in which they describe the roles of entities involved in the action. (the boy kicked the ball) - Agent: the entity that performs the action. - Theme: the entity that is involved in or affected by the action - Instrument: agent uses another entity to perform an action, that other entity is the instrument. - Experiencer: when a noun phrase is used to designate an entity as the person who has a feeling, perception or state. (the boy feels sad the boy= experience) - Location: where an entity is. - Source: where the entity moves from. - Goal: where the entity moves to. Examples of Lexical relations: Synonymy: two or more words with very closely related meaning are called synonyms. It is not necessarily ‘total sameness’. Antonymy: two forms with opposite meaning are called antonyms. Types: Gradable antonyms: can be used in comparative constructions. Also, the negative of one member of a gradable pair does not necessarily imply the other. My car isn’t old ≠ My car isn’t new Non- gradable antonyms (complementary pairs): comparative constructions are not normally used. Also, the negative of one member of a non- gradable pair does imply the other. My grandparents aren’t alive = My grandparents are dead Reversives: we can use the ‘negative test’ to identify non- gradable antonyms in a language, but avoid describing one as the negative of the other. Dress => undress. Hyponymy: when the meaning of one form is included in the meaning of another. concept of ‘inclusion’. Horse is a hyponym of animal, and animal is the superordinate of horse. (higher level). Two or more words that share the same superordinate term are called cohyponyms. Dog and horse are co- hyponyms and animal is their superordinate. Prototypes: the idea of ‘the characteristic instance’ of a category. (best example of a superordinate term). Homophones and homonyms: homophones are two or more different (written) forms that have the same pronunciation. The term homonym is used when one form has two or more unrelated meanings. Polysemy: one form (written or spoken) having multiple meaning that are all related by extension. Example: the word HEAD. Metonymy: relationship between words, based on a close connection in everyday experience. (can be based on many things!). Using one word to refer to the other is called metonymy. Example: king- crown, president- white house. It makes us understand many sentences, such as he drank the whole bottle. Collocation: we organize our knowledge on basis of ‘frequently occurring together’. Pragmatics Pragmatics: the study of what speakers mean. It is the study of ‘invisible meaning’. Speakers must be able to depend on a lot of shared assumptions and expectations when they try to communicate. The investigation of those assumptions provides us with some insights into how more is being communicated than is said. Two types of context: - Linguistic context = co-text. The co- text of a word is the set of other words used in the same phrase or sentence. - Physical context: the physical environment influences our interpretation. Deixis: ‘pointing’ via language. Common words that can’t be interpreted at all if we don’t know the context. Deictic expressions - Person deixis Point to things or people=him, her, those idiots - Spatial deixis Point out locations = here, there, near that - Temporal deixis point to a time = now, then, last week Reference: an act by which a speaker uses language to enable a listener to identify the meaning. Inference: additional information used by the listener to create a connection between what is said and what must be meant. Jennifer is wearing Calvin Klein. Anaphora: referring back to something. We use it in texts to maintain reference. The first mention of the entity is called the antecedent. Presupposition: what a speaker assumes is true or known by the listener. Your brother is waiting outside assumed that you have a brother. Speech act: the main purpose of an utterance. Structure Function Did you eat the pizza? Interrogative Question Eat the pizza (please)! Imperative Command (request) You ate the pizza. Declarative Statement There are two types of speech act: - Direct speech act: when an interrogative structure is used with the function of a question. - Indirect speech act: when a syntactic structure associated with the function of a question (or request) is used. Politeness: in the study of linguistic politeness, the most relevant concept is face. Your face, in pragmatics, is your public self- image. Politeness can be defined as showing awareness of and consideration for another person’s face. Negative face: the need to be independent and free from imposition. I’m sorry to bother you, but.. Positive face: the need to be connected, to belong or be member of the group. Let’s do this together Discourse Analysis Discourse is the language at work: language used in communication. There are rules for who says what, when and how. Discourse Analysis: studying the language at work. Cohesion: ties and connections within text. I killed a mosquito last night. It was bothering me all night, so I had to get rid of it. But: by itself, cohesion isn’t enough! Coherence: everything fitting together Depends on personal interpretation A: Dinner is ready! B: I’m on the phone A: OK. Speech Events There is enormous variation in what people say and do in different circumstances. Speaker- hearer relationship: status, gender, age, etc. influence on what is said and how. General English conversation: - Turn taking - Avoidance of silence between turns - No talking at the same time Completion points: e.g. end of syntactic structure, asking questions. Different conventions of participation Strategies ‘to keep the turn’ Place pauses before and after verbs Put hesitation markers in your speech I mean this other… em… you know… the one which is darker… These strategies are normal in everyday conversation. Speakers are always co-operating Paul Grice: “Make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged.” 4 ´Maxims´, or ´Gricean maxims`: The Quantity Maxim: Make your contribution as informative as is required, but not more or less than is required. The Quality Maxim: Do not say that which you believe to be false or for which you lack adequate evidence. The Relation Maxim: Be relevant The Manner Maxim: Be clear, brief, and orderly Hedges: Words and phrases used to express that we’re not completely sure that what we’re saying is sufficiently correct or complete. Implicatures: The way we actually indicate things without them being stated officially by the speaker, or concluding something out of what has been said. Schema: a conventional knowledge structure that exists in memory Script: Dynamic schema. You have a script for many actions, such as ‘going to the dentist’. What we understand is not necessarily what we read Interpretations are more important than words Language and the brain Neurolinguistics: The study of the relationship between language and the brain. Linguistical areas: - Motor cortex: - Wernicke’s area: - Arcuate fasciculus: - Broca’s area: controls movements of the muscles understanding of speech connection between wernicke’s and broca’s area production of speech The localization view: To suggest that the brain activity involved in hearing a word, understanding it, saying it. Tip of the tongue: we know a word, but it just won’t come to the surface. We have a ‘’word-storage’’ and some words are more easily retrieved than others. When we make a mistake in this retrieval process there are often strong phonological similarities (secant, sextet, sexton…). Other examples are fire distinguisher (for ‘’extinguisher’’), there types of mistakes are called malapropisms. Slips of the tongue: ‘’make a long shory stort’’ ’’use the door to open the key’’, ‘’Black bloxes’’, ‘’Shu flots’’, these mistakes are called spoonerisms. Slips of the ear: ‘’great ape’’ instead of ‘’grey tape’’. Aphasia: impairment of language function due to localized brain damage that leads to difficulty in understanding and/or producing linguistic forms. - Broca’s aphasia: (motor aphasia) o Substantially reduced amount of speech o Distorted articulation - - o Slow speech o Agrammatic speech: the grammatical markers are missing Wernicke’s aphasia: (sensory aphasia) o Produce fluent speech (but doesn’t make any sense) o General terms are used Conduction aphasia: (Damage to the arcuate fasciculus) o Mispronounce words o No articulation problems o Disrupted rhythm (pauses and hesitations) Dichotic listening: left hemisphere dominance for syllable and word processing. Anything experienced on the right-hand side of the body is processed in the left hemisphere and the other way around. The critical period: sensitive period for language acquisition - Lateralization: the apparent specialization of the left hemisphere for language First language acquisition Basic Requirements: - A language-using environment. - Interaction with other language-users. - The physical capability of sending and receiving sound signals. - Sufficient constant input to learn the basic regularities in a language. It’s a biological schedule tied to maturation of the infant’s brain and the lateralisation process. The human brain is lateralised, i.e. it has specialised functions in each of the two hemispheres. It’s dependent on many social factors in the child’s environment. Pre- language stages: the period from 3 to 10 months is characterised by three stages: 1 The holophrastic stage: single word functioning as a phrase or sentence 2 The two-word stage 3 Telegraphic speech: strings of words (lexical morphemes) in phrases or sentences. In these stages the infant is ‘cooing’ and ‘babbling’. - cooing: using velar consonants such as [k] and [g] as well as high vowels [i] and [u]. - babbling: using different vowels and consonants as fricatives and nasals. At the age of 2.5 years: From ‘telegraphic stage’ to introduction of inflectional morphemes Overgeneralization: using / combining inflectional morphemes wrongly Forming questions: First Stage (18-26 months): adding ‘wh-form’ (where, who): Where Kitty? Intonation: Kitty? Second Stage (22-30 months): More different ‘wh-forms’ (what, why): What book name? Intonation: See my doggie? More complex expressions: You want eat? Third Stage (24-40 months): Inversion: I can go -> Can I go? ‘wh-form’ without proper inversion: Why kitty can’t stand up? Forming negatives: First Stage (18-26 months): adding ‘no’ / ‘not’: no sit there / not a teddy bear Second Stage (22-30 months): Addition of ‘don’t’: I don’t want it Addition of ‘can’t’: You can’t dance Placement of ‘no / not’ in front of verb: He no bite you Third Stage (24-40 months): Addition of didn’t: I didn’t caught it Addition of won’t: She won’t let go Late acquisition: ‘isn’t’: This not ice cream used for a rather long period Second language acquisition Dutch Student > studying English in the Netherlands = English Foreign Language (EFL) Dutch Student > studying English in England = English Second Language (ESL) Acquisition: gradual development of ability in language Learning: conscious process of accumulating knowledge of the features of the language Acquisition Barriers: - Teenage / adult age - Lots of other things going on - L1 for daily communicative requirements Affective Factors: Teenagers: more self-conscious Lack of empathy with the other culture Causes: - Dull textbooks - Unpleasant classroom surroundings - Exhausting schedule Methods: Grammar- Translation - Vocabulary lists & sets of grammar rules - Memorization - Emphasis on written language The audio-lingual approach - Emphasis on spoken language - Systematic presentation of structures - Simple to complex - Drills Communicative approach - Reaction against ‘pattern practice’ - Focus on learner instead of textbook, teacher or method - Emphasis on the function of language, rather than form Learning of L2 Transfer - Negative transfer: transferring an L1 feature that is really different from the L2. - Positive transfer: if L1 and L2 have similar features. - Interlanguage: contains aspects of L1 and L2. - Fossilization: the interlanguage fossilizes. Factors that optimize the acquisition of L2 Motivation - Instrumental motivation: learn L2 to achieve another goal. - Integrative motivation: learn L2 for social purposes. Input - Comprehensible. Achieved through: Right level of learning Foreigner talk Negotiated input Communicative competence: The general ability to use language appropriately and flexibly - Grammatical competence: the accurate use of words and structures. - Sociolinguistic competence: when to say what and how. - Strategic competence: organize a message effectively and to compensate for any difficulties. Writing Pictograms: pictures represent particular images (in a consistent way) picture- writing = sun Ideograms: more fixed symbolic form idea- writing; = sun Difference between pictograms and ideograms: difference in relationship between symbol and the entity it represents. They both do not represent sounds or words in a particular language. Logograms =cuneiform writing. The form of the symbol gives no clue to what type of entity is referred to. Relationship between word and symbol has become arbitrary. Word-writing. Rebus writing: combine two symbols to create a word (this one is easy to remember ) Logographic system = writing; Phonographic system = sounds. (The example of the eye / crosseye) Syllabic writing: set of symbols, each representing the pronunciation of a syllable. Last step in development of writing: the consonantal alphabet..