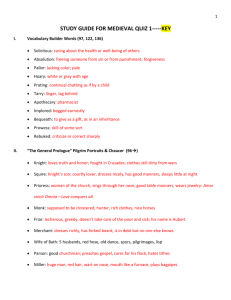

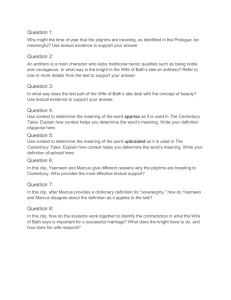

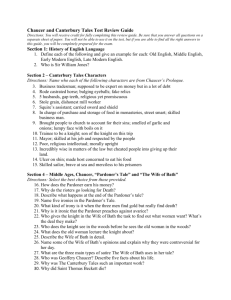

Scott Colleen Scott Dr. Rhonda Kelley World Literature I 26 March

advertisement

Scott 1 Colleen Scott Dr. Rhonda Kelley World Literature I 26 March 2015 3 Reasons Why the Wife of Bath is a Feminist Icon The Medieval Period is certainly not a time period known for being progressive in ideals involving the treatment of women. To most, they were considered the equivalent of cattle that can be taught how to cook and clean. There were dozens of limits as to what a woman wasn’t allowed to do, such as marry without her parents' consent, own a business without special permission, to divorce her husband, own property of any kind (unless she was a widow), or inherit land from her parents if she had any surviving brothers. Usually, the only way a woman of the time could receive an education, including the ability to read and escape the cycle of motherhood, was to join a covenant. Even then, their options were limited usually to midwifery. When all your life and career options fit in one picture, you know things aren’t working in your favor. Scott 2 The time that Geoffrey Chaucer, deemed the “Father of the English literature”, wrote his famous Canterbury Tales was no different in the way society treated women. Feminism wouldn’t even exist as a thing for another 600 years. Yet, it was within the Prologue of the Tales that readers are introduced to a fascinating character that explored the exceptions to the extreme patriarchy established during the time: the brightly-clothed Alisoun, the Wife of Bath. Like many of Chaucer’s characters within the Tales, she is a person of contradiction. Her description and Tale are meant to highlight the corruption of her character and the societal constructs of Chaucer’s time, yet modern readers have taken the Wife of Bath for what she is with positivity: a strong, opinionated, business-wise woman who isn’t afraid of arguing with the men about what marriage is. There are many ways the Wife of Bath can be considered a feminist example in literature, some of which include her Tale, how she’s able to run a business, and how she uses marriage to her advantage. Smashing the patriarchy, 14th century style #3. Her Tale is a Female-central Twist On an Older Folk Story Scott 3 One of the best ways to get an insight on the Wife of Bath’s unique perspective of marriage is to look at her Tale. As the story goes, an Arthurian knight is charged by his court for raping a young maiden and is initially sentenced to death by decapitation. However, King Arthur’s queen, Guinevere, and other ladies of the court intervene on the knight’s behalf and ask the king to give him one chance to save his own life. Arthur agrees to let the women run the show, who present the knight with a challenge: Within a year’s time, he must find out the answer to what women want most in the world. If he finds it and presents it to the court, he is spared. If not, he perishes. He accepts the challenge and sets off across the country, asking various women, but with no straight or same answer. At the end of the year, feeling sorrowful at his fate, he is led to a body of water by dancing fairies, where he finds an old, ugly hag with magical properties. He decides to ask her the question, to which she replies that she knows the answer that will save him. However, she says she will only tell him the answer if she will be repaid later on by the knight. Even the horse is disgusted by her The knight, who doesn’t have any other options to avoid certain death, reluctantly agrees. The old woman whispers the answer in his ear, which he later states out loud to the women of the Scott 4 court, that “Women want sovereignty” over their men and own lives. The court of women agrees and he is set free from death. However, the old woman is present at the court meeting, and states that the knight owes him for the answer he received from her. She requests that he marries her, where the knight proceeds to freak out and despair over marrying an old hag. He begs her to take his material possessions rather than his body, but she refuses to yield, and in the end he is forced to consent. They have a small, private wedding, and the knight is miserable throughout, despite the kindness of the old woman. On their wedding night, while in bed, the old woman asks the knight why he is so sad. He replies that he could hardly bear the shame of having such an ugly wife. Instead of getting angry with him, she offers the knight a choice: either he can have her be ugly but loyal and good, or he can have her young and fair but also coquettish and unfaithful. The knight ponders, and then finally replies that he would rather trust her judgment, and he asks her to choose whatever she thinks best. Because the knight’s answer gave the woman what she most desired, the authority to choose for herself, she becomes both beautiful and good. The two have a long, happy marriage (Benson, 2008). The Tale straight away gives women all of the power, amongst characters such as the Queen, the court, and the old woman, whereas the male protagonist is given hardly any description except criminal, whiny, and then redeemed by a woman. However, while her tale is unique in its girl-power message, it is certainly not a new story. In fact, according to H. Marshall Leicester Jr. of the University of California, the Wife’s tale is a newer take on a far older Irish fable, The Loathly Lady (158). Scott 5 The Original H.A.G. In the original story, the magical old hag, who comes to an inn drenched from the rain, repays the only man of a group of warriors who treats her with kindness and gives her a blanket with her shape-shifting beauty and her hand in marriage, evidence that the “Nice Guy” myth has been around far longer than we thought. Giving the term “m’lady” both more historical context AND sinister meaning The Loathly Lady herself has been featured in many other stories and cultures, most with giving the choice to a male protagonist to either have her as a beautiful, unfaithful wife or an ugly, faithful wife, putting his desire for a loving marriage against his vanity for wanting a trophy wife (Olson, 1995). However, Chaucer makes the necessary change to the Wife’s version Scott 6 of the story by including the idea of women’s sovereignty. Instead of deciding the fate of his wife’s appearance himself and what he wants, the knight in the Wife’s tale leaves the decision up to her. Because he let her choose, he is rewarded doubly with both beauty and faithfulness. That’s a pretty progressive stance in the 14th century. And the Wife of Bath is certainly in a position to want women’s sovereignty, considering… #2. She Ultimately is in Charge of Her Own Affairs Now, to elaborate on the whole women not-being-allowed-to-do-anything bit earlier: most of that extreme patriarchy stuff didn’t apply to those with enough money to live lavishly. According to an article written by Mary Carruthers, the Wife of Bath is certainly not suffering financially, and she probably never had to, because she is born of the bourgeoisie class and that she has accumulated the wealth of having been widowed four times (209). Because of all that extra money just lying around, and the fact that she already has an established place in the upper-class, she’s able to do things that peasant women can only dream of, much like poor women of today. She is “a wealthy west-country clothier” by trade (NOT an artisan weaver), is able to wear massive amounts of expensive red clothing (when dye definitely wasn’t cheap), and to travel leisurely on a religious pilgrimage that she’s already made, like a revisiting tourist to the Bahamas. Shoot, Alisoun’s modern-day equivalent would be five Housewives reality stars combined into one Voltron-style one-percenter with her own fashion line. Scott 7 And she would STILL be more stylish She is ultimately a woman who, despite needing marriage as a financial and social crutch, is used to running her own show and making her own decisions. And readers can tell she likes the autonomy, expressly since… #1. She Twists Society’s Rules to Her Own Advantage The Loathly Lady wasn’t the only thing that Alisoun tweaked to her liking. All throughout her Prologue, as the Wife explains her history as well as her ideals on the subject of marriage and love. In order to back up her eccentric claims, she references several Christian motifs and doctrines to make them sound reasonable. However, even as she alludes to Biblical characters such as Christ and Solomon, it’s obvious to the reader that she is taking a very selfconstrued and liberal interpretation of her religious sources, almost solely for her own benefit and to fit her personal views. Gee, who does that? Scott 8 Caption not needed. According to an article by James Cotter, Alisoun makes a lengthy speech about the concept of “conjugal debt,” but only using half of the original doctrine. The idea of conjugal debt, explained by St. Paul in the locus classicus, is “the theory of a marriage debt” that states that marriage is “a social contract binding two parties to an agreed promise” (169). Essentially, it states that it takes both parties, the wife and the husband, to make a marriage work. However, as Cotter remarks on the Wife’s taking of the doctrine, “She well knows how to use half a truth to argue her whole position.” She only follows the husband-owing-a-debt part of the doctrine, which she uses to argue that her use of husbands for sex is not sinful but sanctified. Her interpretation allows her to call the shots in her marriage and in her bed, showing that she can manipulate the Word of God to her own will as much as her male debaters can. Speaking of which, as you read her Prologue, she even compares herself to the Bible character Solomon in order to justify her plentiful marriages: “Lo, (consider) here the wise king, dan Salomon;/ I believe he had wives more than one./ As would God it were lawful unto me/ To be refreshed half so often as he!” (35-38). Last I checked, it took a large “nether purs” for a woman of the 14th century to compare herself to one of the most famous and powerful kings of the Bible. Scott 9 However, it must be pointed out that the Wife of Bath is certainly not a feminist icon within the most modern context of what it means to be a feminist today. At no point of her Prologue or Tale does she mention a woman’s right to birth control or protection from rape. As a character of 14th century literature, she would have no concept of such recent issues. In fact, as H. Marshall Leicester Jr. points out, the Wife of Bath displays the characteristics of “private feminism,” hence her insistence on women’s desire for sovereignty, rather than “public feminism,” such as the social activism we associate feminism with today (157-158). As we can see, the Wife likes where she is at socially, and certainly wouldn’t want to limit her own freedoms. And again, we’re talking of a time where living on your own as an outspoken woman would earn you the fate of a witch trial. However, within Chaucer’s time period and context, she is certainly strong, female character of her time and times to come. Scott 10 Works Cited Benson, Larry. "The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale: An Interlinear Translation." The Geoffrey Chaucer Page. The President and Fellows of Harvard College, 8 Apr 2008. Web. 6 Apr 2015. Carruthers, Mary. "The Wife of Bath and the Painting of Lions." PMLA 94.2 (1979): 209-222. Modern Language Association. Web. 5 Apr 2015. Cotter, James Finn. "The Wife Of Bath And The Conjugal Debt." English Language Notes 6.3 (1969): 169-172. Humanities International Complete. Web. 6 Apr. 2015. Leicester Jr., H. Marshall. "Of A Fire In The Dark: Public And Private Feminism In The Wife Of Bath's Tale." Women's Studies 11.1/2 (1984): 157. Sociological Collection. Web. 5 Apr. 2015. Olson, Glending. "The Marital Dilemma In The Wife Of Bath's Tale: An Unnoticed Analogue And Its Chaucerian Court." English Language Notes 33.1 (1995): 1-7. Humanities International Complete. Web. 5 Apr. 2015.