Hasan, Ruqaiya. 1995. The conception of context in text. In Peter H

advertisement

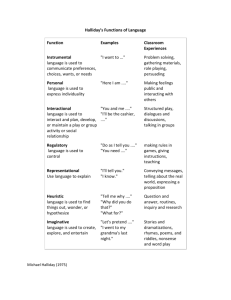

PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Abstract Register is, for Halliday, “the necessary mediating concept that enables us to establish the continuity between a text and its sociosemiotic environment” (Halliday 1977[2002]: 58). Halliday and Hasan have both argued that register must be seen as a function of all the three vectors of the context of situation: field, tenor and mode. Hasan has further argued (e.g. Hasan 1985/89) that register consistency is reflected in text structure, while intra-register variation comes from “the opportunistically selected meanings” determined by the “here-and-now-ness of that particular interaction” (Hasan 1985/89: 114). When context is modelled via a system network (Hasan 1999, 2004, 2009a), one can argue that “the primary options of the contextual system networks realize the structure of the text while the more delicate ones realize its texture” (Hasan 2004: 25). But with a range of resources available for the creation of texture (Halliday and Hasan 1976; Hasan nd., 1984, 1985/89, forthcoming) what might the take up of different texture-creating relations across different instances of a register mean for claims about register consistency and variation? The data for this exploration comes from the analysis of aspects of the “cohesive harmony” (Hasan 1984) patterns in two contrasting instances of news. The paper argues the potential of Hasan’s cohesive harmony schema is not only in the measurement of coherence in quantitative terms, but for what can be revealed about the principles of continuity on which an instance of text is based. These principles must also be related to register, and specifically to intra-register variation (Hasan 1985/89, 2004). Is it possible also to claim that the degree of potential variation in the modes of texture production is also a means by which registers vary? In other words, are some registers more or less constrained than others, with respect to the principles by which the text gets from its point of departure to its resting point? Text-in-context: texture and structure in registers of news annabelle.lukin@mq.edu.au Department of Linguistics Macquarie University Language is not realized in the abstract: it is realized as the activity of people in situations, as linguistic events which are manifested in a particular dialect and register (Halliday et al. 1964[2007]: 18) Introduction: context and register in Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics To understand Halliday’s conception of language, one must fully understand the place of register in his systemic functional account of language. Attention to Halliday’s discussions of the term register will leave any reader with the view I am putting here: that register is central, perhaps the most central, concept, in Halliday’s systemic functional theory of language. The quote above is one example of what I mean: in this quote from a (1964) paper, Halliday argues that register is fundamental to the process of language-made-manifest. Language is realized in “the activity of people in situations”. The process of actualising language is a process of language shaping, and being shaped by, the people using it, the activities for which it is being used, and the mode/s through which language contact takes place. The combination of these factors at work unify into a text, a text which reflects and expresses the forces under which it Page 1 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION came into being. Thus, the notion of register explains the process and pressures under which language manifests. To know a language in any practical sense is to be able to operate through language in some set of socially and culturally constrained situations. For a theory committed to the view that language is only viable in a social situation, as Halliday’s theory is, register must be “the necessary mediating concept that enables us to establish the continuity between a text and its sociosemiotic environment” (Halliday 1977 [2002]: 58, emphasis added). Halliday describes register variation as a function of settings in the field of discourse, the mode of discourse and the tenor of discourse (Halliday et al. 1964[2007]: 19). These terms are peculiar to systemic functional linguistics, although they came out of a preoccupation with the notion of context as a necessary part of a description of language in process. Malinowski’s concept of context of situation was brought into linguistics by Firth, who proposed his own schema for explaining the elements of a situation, as did Hymes (see Halliday 1985/86). For Halliday, register is the linguistic expression of settings in context; it is a descriptive term for settings in language. It is “the critical intermediate concept…which enables us to model contextual variation in language” (Halliday 1995[2005]: 248, emphasis added). As “the critical intermediate concept”, register looks in two directions: towards an instance of language use, the individual text under description, and towards the semiotic potential of the language system. The relation between an instance of language (realized as text) and the system of language is part of resolving the ‘langue’ and ‘parole’ distinction of Saussure, since, as Halliday argues, “there is only one phenomenon here, not two: langue and parole are simply different observation positions” (Halliday 1995[2005]: 248). Hasan has noted that in SFL, the conception of context – as field, tenor and mode - has been used “as a device for placing grids on language use, thereby introducing system into parole” (Hasan in press: 14). Halliday’s conception of the text-register-context relation is not uncontested. Martin (1992) presents arguments for his genre model; van Dijk (2008) argues the systemic conception of context is “misguided” and “needs to be abandoned” (2008: 28). Yet as Hasan has argued, the descriptive architecture necessary to fully examine the validity and robustness of Halliday’s model is itself a work in progress. For instance, while field, tenor and mode are considered central to Halliday’s conception of the relations of text to context, these terms have been largely treated by systemic linguists as if self-evident (Hasan 2009a). There have been some attempts to systematize their operationalization, including Butt (2003), Hasan (1995, 1999, 2004, 2009a), Martin (1992), Matthiessen (1993), Matthiessen et al (2008), and Bowcher (2007). These descriptions are preliminary attempts to systemize the ‘realizable’ at the stratum of context. That is, by describing “contextualisation system” (Hasan, 2009a), these theorists are attempting to describe that which is outside of language but which is overwhelming realized in language. If, as is widely accepted by systemic linguists, text is the realization of a context of situation, then such descriptions of contextualisation systems constitute an exploration of this fundamental linguistic relation, described by Halliday as “probably the most difficult single concept in linguistics” (Halliday 1992[2003]: 210). My object in this paper is to add to the literature within this particular part of the systemic tradition by exploring two news texts, and what can be said of them with respect to their registerial properties, and therefore, what they might be said to be Page 2 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION doing as context-realizing structures. The paper is meant as an exploration of the robustness of Halliday’s claims concerning text-in-context relations, with a particular concern for the role of texture in the experience of text-in-context. At the same time, the paper extends a long tradition in linguistic studies of news discourse (the literature is too vast, but see Lukin in press a, Matthiessen, in press, for some reviews of this work). Like much of this scholarship, my research has also been concerned with news as a symbolic commodity, the business of which is the purveying of forms of consciousness (e.g. Bernstein 1990; Boyd-Barrett 1998; Hall et al. 1978; Herman and Chomsky 1998). If news has this power to shape minds, to be a mechanism for the distribution of ways of seeing, then the processes of text formation which enable news must be significant to how it functions. In other words, if news distributes forms of consciousness in particular ways, the mechanics of this process must in some way be linked to the discursive shape or shapes news takes. Its discourse shape(s) must be relevant to understanding what vistas are provided to consumers in their interactions with news. So, what about the experience of ‘textness’ needs to be understood to explicate the function of news as symbolic control? In this paper, I want to explore these ideas in the context of the reporting of a very controversial and consequential set of events from March, 2003, namely, the “Coalition” invasion of Iraq (e.g. Stiglitz and Bilmes 2008; Otterman et al. 2010). For space reasons, a single television news report from Australia’s public broadcaster, the ABC, is analysed with respect to the principles by which, in the unfolding of the text, situational coherence is achieved. The examination of such principles draws in many aspects of linguistic choice, and demonstrates the playing out of Saussure’s syntagmatic and paradigmatic axes. It also helps understand how certain ways of framing news content can be regularized (as discussed e.g. in the work of Entman 1994). The structure of this paper will be as follows. First, I consider briefly the key concepts in a Hallidayan model for relating text to context of situation, and to society. Then, I consider the notion of text in the systemic model (e.g. Hasan 1985/89, forthcoming), and discuss relevant claims about structure and texture as two vectors of continuity in a text. In the discussion of texture, I illustrate the principles using a news text drawn from an online newspaper (The Sydney Morning Herald online), reporting the case of Scooby, a “tiny, deaf, aging” Charles Spaniel stuck in a cave. This text is intended to be contrastive with the main text I will analyse, the ABC TV news report from March 20th, 2003. The systemic description of text (register) in context Figure 1 presents the most efficient summary of the first principles in a systemic exploration of the text-in-context configuration, bringing four key concepts (text, context, language, society) together via two key relations (realization, instantiation). The concepts linked on the horizontal vectors are related by the principle of instantiation. Thus, in Halliday’s theory, a text is an instance of the language system; and a context of situation is the instantiation of some kind of social/cultural practice, i.e. society is the sum of what people do when they are interacting. Simultaneously, along the vertical vectors, a relation of realization pertains. As has been insistent in Halliday’s work, the realization relation is bidirectional. Thus, a text both creates and is created by its context of situation; language is both created by and creates, along with other semiotic systems, society, i.e. our ways of doing and being. Page 3 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Figure 1 Text in context, language in society (Hasan 2009b, adapted from Halliday 1999) Hasan argues that “text and context are so intimately related that neither concept can be enunciated without the other” (Hasan 1985/89: 52). Turning now specifically to the notion of text, Hasan argues that its central attribute is that of unity, and that the unity of text is of two kinds: unity of structure and unity of texture. Both of these dimensions are systematically related to the contextual configuration, i.e. to the particular settings in field, tenor and mode of which a particular text is the realization. Text, including its structure and texture, is the expression of the contextual variables field, tenor and mode (Halliday 1977[2002], 1985/89; Hasan 1985/89, 1995, 1999, 2009a; Matthiessen 1993). Thus: Both [texture and structure] can be traced back to the role of meaning in realizing the elements of textual structure, which occur not by force of some immanent ‘rule’; nor are they imposed by an authority external to the practising members of community; they occur only by way of language performing some specific function in the relevant activity, and so constitute a record of social practice. (Hasan 2004: 23-4 ) In relation to the description of text structure, Hasan proposes the notion of GSP, which requires an analyst to specify with respect to the text’s structure: 1. What elements must occur; 2. What elements can occur; 3. Where they must occur; 4. Where they can occur; and 5. How often they can occur. Such a description generates a generic structure potential, which, if the description is robust, should encapsulate all possible structures for that register. Hasan has argued “there exists a wide range of genres [registers - AL], varying in the extent to which the global structure of their message form appears to have a definite shape” (Hasan 1985/89: 54). Texture is also fundamental to the construction of text. Since everything in discourse is “beholden” to the contextual configuration (Halliday and Hasan 1985/89; Hasan 2004), the means by which a text gets from its point of departure to its resting point must also be both activated by, and active in the construal of, the context of its operation (Hasan 2009a, etc). Thus, “the facts of texture construe the very detailed aspects of the situation in which the text came to life”; situation type is “the motivating force of texture” (Hasan 1985/89: 115). Page 4 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION metafunction rank clause [class] phrase [prepositional] [verbal] group ideational logical experiential TRANSITIVITY complexes (clause- phrasegroup- [nominal] [adverbial] MINOR TRANSITIVITY INTERDEPENDENCY (parataxis/ hypotaxis) & TENSE LOGICALSEMANTIC RELATION (expansion/ projection) MODIFICATION MODIFICATION word word) DERIVATION inform ation unit info. unit complex complexes ACCENTUATION EVENT TYPE ASPECT (nonfinite) THING TYPE CLASSIFICATION (DENOTATION) simplexes Figure 2 Halliday’s function/rank matrix (Halliday 2009; see Halliday 1971 for earlier version) *Lexical cohesion is not included in Halliday’s diagram. I have added it here. Page 5 9/02/16 interpersonal textual MOOD MODALITY POLARITY THEME CULMINATION VOICE MINOR MOOD (adjunct type) FINITENESS CONJUNCTION VOICE DEICTICITY PERSON ATTITUDE DETERMINATION COMMENT (adjunct type) CONJUNCTION (CONNOTATION) KEY INFORMATION (cohesive) COHESIVE RELATIONS REFERENCE SUBSTITUTION/ELL IPSIS CONJUNCTION *Lexical cohesion PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION The work of texture in text in context As Hasan has argued, text has the property of coherence. While cohesion is “the foundation on which the edifice of coherence is built”, it is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the achievement of coherence (Hasan 1985/89: 94). It is for this reason Hasan developed the method of analysis she called cohesive harmony. Cohesive harmony is “the manifestation of the topical continuity of a text” (Hasan n.d.: 71). Cohesive harmony analysis brings together grammatical and lexical selections and relations across Halliday’s metafunctional spectra. Figure 2 is Halliday’s function/rank matrix, a representation of the grammatical systems of English in relation to their location with respect to metafunction and rank. Systems relevant to cohesive harmony analysis appear in bold and italics. Coherence is a semiotic phenomenon. As Hasan has argued: A situationally chaotic scene of some accident, or a fight, for example, can be rendered coherently in a text. And to this extent, situational coherence is not a prior requirement for the existence of coherence in a text which describes these situations. Coherence is not a picture of reality; it is a representation – just like other semantic phenomena in language. The coherence arises from the imposition of a grid upon sensory precepts; the categories of cohesion are the lexicogrammatical indication of the details of such a grid (Hasan 1984: 210). That a text requires texture presupposes that coherence, based on continuities of some kind, is possible even with respect to complex events constantly in flux. Somehow, even in the most chaotic of situations, the textual function can work its magic, “creating a parallel universe” (Halliday 2001[2003]: 276), and in so doing enabling some user/s to bring coherence to such chaos. Hasan’s cohesive harmony framework is one method to bring out the basis for the creation of texture in a given instance of a register, keeping in mind that “the attribute of texture is itself controlled by ‘compatibility’ of meanings” (Hasan n.d.:1). Table 1 Resources a speaker of English has in the system for indicating the semantic bonds between parts of his/her utterance (Hasan 1984, from Halliday and Hasan 1977) I REFERENCE 1. pronominal 2. definite article 3. demonstrative 4. comparative II SUBSTITUION & ELLIPSIS 1. nominal 2. verbal 3. clausal II LEXICAL 1. reiteration a) repetition b) synonymy c) super-ordinate d) general word 2. collocation IV CONJUNCTION 1. cohesive conjunctive a) additive b) adversative c) temporal d) causal 2. continuative There are two principles of continuity in the creation of texture: chain formation and chain interaction (Hasan n.d. 1984, 1985/89, in press). With respect to chain Page 6 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION formation, Hasan has proposed three types of semantic relations: co-reference, coclassification, and co-extension. Co-reference is a cohesion relation of “situational identity” (Hasan n.d., 1984). In co-reference, the cohering element refers to the self same thing as the element with which the tie is formed. Co-referentiality is typically realised through the devices of reference: i.e. pronominals, the definite article, and by demonstratives (see Table 1). Under some circumstances, it is possible to express this relation by lexical cohesion alone, e.g. through repetition (Hasan 1984: 187). But repetition, even of a proper noun, does not of necessity express a relation of coreference. So, for instance, a lexical item like Iraq has more than one meaning. It can be a geographic entity or a geopolitical one, and only co-text can resolve which of these meanings is being construed in a given text moment. Thus, relations of coreference are always text bound. Co-reference underpins the formation of identity chains (hereafter “IC”). Appendix 1.1 sets out a text for illustrative purposes. It is from an online newspaper article, titled “Scooby in a scrape: rescue op to save him from cave”, a report about a “tiny, deaf and ageing…Cavalier King Charles spaniel” stuck in a cave in the Hunter Valley of NSW. (Note: the text has been divided into the unit of message (36 in total), following Hasan 1996). Table 2 is an instance of an IC, from the text. The numbers indicate the message in which the lexical item is found. This IC is the first chain in the series. The text begins its unfolding with the lexical item “Scooby”. This IC also has the feature that it is text-exhaustive, i.e. its domain is the whole text. One might use the metaphor of a “backbone” to describe its contribution to the texture of this text. The chain is built largely through pronominalisation; in addition, repetition of a proper noun (Scooby), and the use of the definite article (the dog) contribute, albeit minimally, to the tracking of the article’s central protagonist. Appendix 1.2 presents the full set of identity chains in the Scooby text, eight in total. Hasan (1984: 204) has argued “The identity chain (IC) is a requirement for the construction of the text because the entities, events, circumstances that one is talking about need to be made specific if there is to be repeated mention of the same”. The absence of identity chains would mean the text “ha[s] no means for building specificity” (Hasan 1984: 206). Appendix 1.2 shows all the ICs for the Scooby text, of which there are eight in total, six of which have only two or three tokens. Table 2 Identity chain in online newspaper article, “Scooby in a scrape: rescue up to save him from cave” message # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Page 7 Token Scooby him a dog Scooby spaniel his He he he he 9/02/16 message # 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Token Token Scooby message # 19 20 21 22 23 he ^HE the dog he 24 25 26 27 his he him him he he message # 28 29 30 31 32 Token him he Scooby him He; his 33 34 35 36 him he his him PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION In Hasan’s cohesive harmony framework, identity chains are in a contrast with similarity chains (hereafter SC). Underpinning similarity chains are the relations of co-classification and co-extension. Co-classification is the relation formed by two tokens of the same class of thing. Co-classification is typically realized by substitution/ellipsis, as well as comparative reference. A relation of coextension is formed when a lexical item echoes another by being part of the same “semantic field”. Relations of repetition, synonymy, antonymy, hyponymy, meronymy are relevant here. Table 3 is an example of an SC from the Scooby text. The chain consists of processes of movement in space, processes in which, for the most part, Scooby is Medium/Actor (Halliday and Matthiessen 2004). The relations between these items is based on lexical cohesion, with the principle being that of co-extension. That is, the tokens are part of the same semantic field. Table 3: ‘Similarity chain’ in Scooby text message # 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Token chase ran up come back walk out message # 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Token message # 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 travelled walk out Token standing up moving around laid down Coherence, as noted, does not emerge simply through the continuity which underpins chain formation. Coherence is not only about invoking similar kinds of things. As Hasan has argued, ‘When speakers are engaged in the process of creating coherent text, they stay with the same and similar things long enough to show how similar the states of affairs are in which these same and similar things are implicated’ (Hasan, 1985/89: 94). Coherence requires both ‘warp’ and ‘weft’. Thus, the next step in the analysis is to look at what functional relations obtain between the cohesive chains, in other words, how the chains interact. Since coherence is coherence with respect to some view of the world, Hasan draws on the relations of Halliday’s experiential grammar to consider how chains interact. Continuity requires at least two tokens in a chain to display similar experiential relations with at least two tokens of another chain. Tokens in a chain which interact through similar experiential relations with another chain are considered central tokens because of their contribution to the creation of continuity across two axes. Table 4 shows the relations between the identity chain relating to “Scooby” (Table 2), and the similarity chain featuring processes relating to movement in space (Table 3). Of the eight tokens in the similarity chain, seven are central tokens, by virtue of the fact they are in a relation of Process to Medium (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004) with part of the “Scooby” chain. Table 4: An example of chain interaction in “Scooby” text. 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Page 8 Medium He he he he 9/02/16 Process chase ran up come back walk out 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Medium Process - travelled he walk out 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Medium Process he he standing up moving around he laid down PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Table 4 shows a further principle of texture, according to Hasan, which is that texture is a lexicogrammatical phenomenon, i.e. it is construed in the interaction of grammatical and lexical cohesion. A text requires both identity chains, based on coreferentiality, and similarity chains, based on co-classification and co-extension. Thus, “in a normal non-minimal text, the presence of both types of chains is necessary” (Hasan 1984: 206; also n.d.: 70). Hasan notes that the requirements of both chain formation and chain interaction show that coherence is a function of both Saussure’s syntagmatic and paradigmatic axes. Identity and similarity chains constitute the expression of paradigmatic relations. Each of these paradigms “represents a relatively self-contained center of unity” (1984: 218) and “when through chain interaction these centers of unity are brought together, this yields cohesive syntagms” (1984: 218). For illustrative purposes I have separated ICs and SCs. In the context of practical analysis, the presence of a cohesive tie is the principle on which one would assign a token to a cohesive chain in a text. Tokens in a text cohere with other tokens through both relations of identity and relations of similarity. In a standard cohesive harmony analysis, ICs 2-4 (which construe the rescue team) would be considered to form one single chain. A chain formed by relations of both identity and similarity Hasan calls a bifurcated chain (n.d.: 70). Appendix 1.3 is shows central tokens, i.e. those tokens where at least two in a chain interact with at least two of another chain (the nature of the chain interaction has not been shown, as this would significantly affect the readability of the diagram). As noted earlier, the shows the text’s preoccupation with a single instance of one and the same dog. Central to the text is the self-same instance of one particular dog. When the interactions of this chain are considered, we see that 28/36 messages have Scooby as nuclear participant of a clause. In Halliday’s description of transitivity roles, Scooby is Actor (so he could walk out again), Goal (A crew of six rescuers are today trying to coax a tiny, deaf and ageing dog…) and Carrier (he may be a little bit dehydrated and confused). The text moves around a semiotic space consisting of angles on Scooby; the text’s movements consist in different transitivity configurations around Scooby. Actions by and to Scooby, Scooby’s state of being and mind, and location, are construed through lexical relations. But the text stays with the same individual instance of the category ‘dog’. This kind of news report can be distinguished from those which take an individual instance (human, animal) as the departure point, but the text moves from the vignette to a preoccupation with a wider phenomenal realm. Analysing context of situation What do these linguistic patterns realize? What kind of context do they both create and express? The short answer is “news”, but the term describes the phenomenon at a high order of generality. Figure 3 displays Hasan’s network for the contextual parameter of field. It is intended as a beginning description in the process of elaborating the dimensions of context realizable in language. The network has four systems: MATERIAL ACTION, VERBAL ACTION, SPHERE OF ACTION, and ITERATION. With respect to the first system, the “Scooby” text has the feature [non-present: absent]. The contextual features which the “Scooby” text realizes are annotated by the use of the symbol . With respect to verbal action, the text has the feature [constitutive: conceptual]. These are features that go together. The absence of exophoric reference in the Scooby text is some basis for the claim that the context of situation of this text has these features. From [conceptual], Hasan hypothesizes three Page 9 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION simultaneously systems. For space reasons, I will refer only the third of these, for which the first decision is the choice of [informing] versus [narrating]. The particulars of this news text, as they are revealed in the texture analysis, suggest the following selection: [narrating:recounting:personal:other]. Chain formation and interaction are the basis for making these claims. The individualism of the identity chain illustrated above is a sign of a text that is [personal: other]. The process chain builds a field of related action, action consistent with a notion of “recounting” of events as one dimension of this social action. Figure 3 Field network, combining Hasan 1999, with additions from Hasan 2009a; annotated with respect to Scooby (★) and Iraq war text (✪) Coherence in a complex text: reporting “the war against Iraq” I now want to consider a TV news text, from ABC TV’s reporting of the invasion of Iraq, in March 2003 (see appendix 2.1 for transcript of text in messages; the transcript takes in the bulletin preview and overview (messages 1-16) and the first report of the bulletin (messages 1-33; note the restart of numbering which appears in some chain presentations below)). Examining the texture of such a texts, i.e. examining “the minutiae of utterances” (Hasan, et al, in prep), provides a window into the mechanics Page 10 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION of language doing its work as “symbolic control”. The text I will examine is the first news report broadcast on the evening of the date taken to be the beginning of the “Iraq war” (Lukin in press a). At the time, the ABC had a considerable investment of its public resources into the reporting of “the war”, with fifteen foreign correspondents involved in reporting the invasion from Iraq, around the Middle East, Europe, and most importantly, Washington, where five of its correspondents were located. The data from this period of reporting an event of such huge consequence provides a basis for further examinations of state and media relations (e.g. Robinson et al. 2009; Herman and Chomsky 1988 [2002]; Lukin 2012; see also NYT journalist Dvid Barstow’s investigation of the ‘military-media-industrial complex: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2008/04/20/washington/20080419_RUMSFELD. html?ref=davidbarstow). The text has two modalities in play, language and moving image. While the Scooby text has a photograph of the “rescue operation”, and may fit some scholars definitions of a multimodal text, the verbal text in no way depends on the visual for the achievement of the status of “text”. The television text, by contrast, somehow integrates various presentation modes, such as the “voice over” (where the journalist appears outside of the material location presented in the visual mode), “vox pop” (in which some speaker is made relevant to the news item through the selection of commentary interwoven with the text) and “stake out” (where the journalist speaks “on location”) (Hartley 1982). The term “vox pop” is hardly appropriate in the context of the text analyzed here, as Hasan has pointed out (personal communication). The TV news text is different in another important respect. The Scooby story was all over in one news report. The value of the social activity was such that completion could be achieved in one text instance – in other words, with respect to the parameter PERFORMANCE OF ACTION, in Hasan’s field network (see Figure 1), the text displays the feature [bounded]. By contrast, the value of the social activity of reporting the invasion of Iraq at this time put it in a different class, in which, with respect to the parameter PERFORMANCE OF ACTION, the text displays the feature [continuing: sequenced]. Table 5 Dominant cohesive chain in "Iraq" text (asterisk indicates exophoric item) message # Token message # Token message # 1 11 attack 2 war against Iraq attack disarm 3 free 13 attack 7 4 *this campaign 14 campaign disarm operate 8 9 12 5 15 6 16 7 Page 11 war 9/02/16 1 message # Token message # 5 15 conflict 25 6 16 conflict 26 war 17 *this campaign 27 this 18 28 this 19 29 campaign 20 30 21 31 10 shots war 11 Token blasts *it campaign war fire explosions Token PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION 8 9 air raid go off explosions rock 2 3 13 strike 4 14 10 attack strikes 12 22 operations disarm free defence 32 23 strike 24 bombing 33 The text constitutes the first report of the first bulletin covering the invasion of Iraq. The text, as such, bears the weight of being the first “toe in the river” in the reporting of these events on what was then the primetime ABC news bulletin. Table 5 shows the dominant cohesive chain of the text; tokens in this chain turn up in 27 out of a total of 49 messages. By contrast with the “Scooby” text, the dominant chain is a bifurcated chain, a chain in which there is a mix of relations of co-reference and coextension. Thus, the text’s development is not through the filling out of a set of events or circumstances pertaining to one individuated entity. This means the main chain of the text involves both grammatical and lexical cohesion, and that to the degree that the text has continuity, it does so through a mix of tracking the identical instance of something, as well as bringing into the picture other things that relate to that entity through relations of lexical cohesion, such as synonymy/antonymy (“strike” – “attack” – “defend”), hyponymy (“shots” – “strikes”), and meronymy (“war” – “air raid”). Appendix 2.2 presents the ICs for the “Iraq” text. The presentation of ICs for this text is not without its difficulties, and indeed ambiguities. The lexical item “Iraq” for instance is distributed across two ICs in order to account for the distinction between “Iraq” in Tonight the war against Iraq begins with Baghdad under attack and “Iraq” in Within 90 minutes of the deadline passing [[for Saddam Hussein to leave Iraq]], American bombers attacked military targets around Baghdad. In the latter, the meaning is the physical territory of Iraq, while in the former, the notion is something more abstract, like a geopolitical entity, i.e. the “state” of Iraq. The meaning of “Iraq” in “the war against Iraq” is this abstract idea, by contrast to the meaning of “Iraq” in “the war in Iraq”, where the item refers to a geographically bounded entity; this leaves as an open question the meaning of “Iraq” in “the Iraq war”. The term obscures the initiators of “the war”. In addition, the text has exophoric reference (e.g. IC8, IC9). The exophora in this environment is not to a “material situational setting”, since the news producer and news consumer do not share any such kind of setting. IC8, for instance, is a miminal chain of two exophoric items, while IC9 the meaning of “we” has to be inferred, and there are at least two possibilities. Exophoric presupposition, argues Hasan, “results in the specific meanings remaining implicit to all decoders except those who ‘hold the key’ to all significant elements of the contextual configuration” (nd.: 11). The exophora derives from the fact that the language functions in an environment in which another modality is also operating (and thus this text is analysed, with respect to the system of MATERIAL ACTION Hasan’s field network, as [non-present: virtual], by contrast with the “Scooby” text, where MATERIAL ACTION is [non-present: absent]. Despite the parallel modality, the exophora is not disambiguated for viewers. The effect is to create an “as-if” sense of proximity to the events, but at the expense of an experiential representation of the events. This is some evidence to claim that the orientation of the text, with respect to Hasan’s distinction of [relation-oriented] versus [reflection-oriented] is towards the former. Page 12 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Table 6 Some identity chains (ICs) from "Iraq" text; KEY: Underline means the token enters into clausal configuration; strikethrough means token is relevant but not central, or central only through continuity at group but not clause rank (see below). message # 1 IC1 the war against Iraq message # 9 IC10 7 1 the 2nd Gulf War the war 7 11 10 this war 2 26 27 28 13 the war this this 10 24 a series of explosions the first blasts ?explosions message # 10 13 1 IC11 This initial strike ?the opening shots of the war ?a limited series of missile strikes ?it ?the bombing There is other evidence to suggest that the driving force of the text is not experiential. Consider chains IC1, IC10, and IC11. As noted, these chains would be combined in the process of a full cohesion and cohesive harmony analysis. When separated, however, the problems of texture-making in an environment such as this are put on display. These chains are involved in the work of the text making sense of events both “on the ground” – the visible or observable actions and their effects (strikes, explosions) – and with the integrating principle that unifies these actions (the war against Iraq). IC1 contains the token which initiate the chain concerned with the events to hand; it is predicated on the war against Iraq being a viable shorthand mode of reference to construe the recently transpired events. The term was so much in the zeitgeist that it may not seem worthy of questioning. Yet “war” is not given in the concrete events that can be witnessed. It is a explanatory principle, that organizes and legitimates them. A contrasting construal of these events can be seen in the writing of the British foreign correspondent, Robert Fisk, who wrote of these same events without calling them “the war against Iraq” or any near versions of this, such as “the Iraq war”: his global abstraction for referring to the events was “this violence” (article published by The Independent, republished on the web here: http://truthout.lege.net/docs_03/032503D.shtml). As Halliday notes, lexis is “the product of the intersection of a large number of classificatory dimensions’ (Halliday 1966: 149). Lukin (in press a) explores the consequences rhetorically and ideologically of the choice of “war” to explain the events under focus. The analysis presented here shows that the notion that the visible events constitute “war” is the one aspect of the “existential fabric” (Butt 1988) of the text about which there is specificity and definiteness. Once “the war against Iraq” is invoked, it can be pronominalised, and reduced to simply “the war”. By contrast, the representation of the actualised events lacks definiteness and specificity. IC 10 contains tokens construing the consequences of action by “Coalition” forces: “a series of explosions” is presumably the self-same explosions of “the first blasts”; but later in the text we find reference simply to “explosions”. This links to the other references through lexical, but not grammatical cohesion. Why does this matter? As Hasan notes, while pronominals and the deictic the are implicit, they are definite in their meaning. Lexical items, by contrast are explicit and indefinite (nd.: 59). Does “explosions” refer to those mentioned earlier in the text? In the absence of grammatical cohesion, one cannot be entirely sure. This problem holds with IC 11: lexically, the items Page 13 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION “strike” “shots” and “bombing” are close synonyms, presumably referring to the unidirectional action by “Coalition” forces. Yet the journalist uses these terms in both singular and plural form. Thus “the opening shots of the war” seems to refer to the self-same event as “this initial strike”; “this initial strike” would similarly seem to be the same event as “a limited series of missile strikes”. At the very least, one must conclude that the news report is not concerned with a close and detailed account of these events, since it seems to disregard the significance of whether the visible events constitute one or many things. Thus, the texture becomes ambigious, at the point at which the observable phenomena are being construed. What is significant is that the actualized violence which initiated the invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq was not reported in any detailed sense. This news report was the first of twelve reports in the bulletin, and none of the following eleven revisited the issue of what the Coalition forces had actually done to or in Iraq on that day. The extent to which the visible events are “covered” in the text analysed here is the full extent of the reporting by ABC TV of those events. Thus, the text does not invite the reader to hold his or her attention to the specifics of the Coalition’s attack on Baghdad on this particular day. This textural looseness has implications then for the second dimension of texture, that of chain interaction. The tokens in the chains displayed in Table 6 are underlined where they constitute central tokens interacting as groups entailed in clause configurations. Those which are displayed with a strikethrough are tokens which either do not enter into chain interaction, or do so only by virtue of group internal interaction. In addition, as can be seen from the list of ICs, there is no chains in the text pertaining to Coalition forces or troops; the text has acts of war, without their perpetrators. As I have shown elsewhere (Lukin in press b), in a text in which there are both chains construing acts of war/violence, and chains concerned with the agents of same, these chains do not interact in course of the text: the belligerents and their acts of war do not interact for the purposes of the construal of “compatible meanings”. These claims are the basis for my analysis of the field (annotated onto Figure 3 using the symbol ) of this text as [constitutive: conceptual: informing: commenting]. Conclusions The discussion of the significance of the cohesive harmony patterns in the ABC TV news text is somewhat truncated, but I believe I have illustrated the potential of Hasan’s framework as a means for exploring more delicate features of the context work done by texts. The testing and development of cohesive harmony should be of interest to those concerned with the problem of text making, i.e. how it happens, and what the critical vectors of variation are, and the contribution of texture to the realization of features of context. In respect of the “Iraq war” text, the analysis shows a textual looseness, which has consequences for the kind of vista of these events which the ABC was making available to its viewers. It may be argued that this looseness is a consequence of the fact that the language is working alongside another modality; but Lukin, 2003, reports a similar pattern in the analysis of literary criticism. In particular, the analysis from this text show a text trajectory in which specificity, definiteness and continuity on experiential grounds is not prioritized. But the text’s status as news is in no way at risk; the register is such that quite different modes of texture building are both viable and that, as Hasan has postulated (Hasan 2004) what these differences construe are more delicate features of context. The register can accommodate two very different texts; different when viewed at this level of delicacy. The analysis presented here is further evidence (see e.g. Lukin in press b) Page 14 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION for the claim that a central property of news is the experience of shifts along the kind of cline of (de)contextualisation described in Cloran. The analysis is also suggestive of the tendency claimed by Halliday (2010: 5) to be a tendency in 21st century patterns of language use, where both interpersonal and textual meanings take on a new prominence, though for different reasons: the textual in integrating the various semiotic strands, with the interesting consequence that it becomes less explicit in the text, rather like the subtitles in a foreign language movie; the interpersonal on the other hand becoming more explicit as the exchange of meanings becomes increasingly individualized and personalized. Page 15 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Bibliography Bernstein, Basil. 1990. Class, Codes and Control, Volume IV: The Structuring of Pedagogic Discourse. London: Routledge. Boyd-Barrett, Oliver., & Rantanen, Tehri. 1998. The Globalization of News. In O. Boyd-Barrett & T. Rantanen (Eds.), The Globalization of News. London: SAGE. Bowcher, Wendy. 2007. Field and multimodal texts. In R. Hasan, C. Matthiessen and J. Webster (Eds) Continuing Discourse on Language: A Functional Perspective, Volume 2. London: Equinox. pp619-738. Butt, David. G. 1988b. Ideational Meaning and the existential fabric of a poem. In Robin Fawcett & David Young (Eds). New Developments in Systemic Linguistics: Vol. 2 Theory and Application. London and New York: Pinter. Butt, David. G. 2003. Parameters of Context. Department of Linguistics, Macquarie University. Entman, R. M. 2004. Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and US Foreign Policy. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. Hall, Stuart, Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke and Brian Roberts. 1978. Policing the Crises: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education Ltd. Halliday, M. A. K. 1966. ‘Lexis as a Linguistic Level’, in C. E. Bazzel (Ed) In Memory of John R. Firt, London: Longman. Halliday, M. A. K. 1977[2002]. Text as semantic choice in social contexts. In J.J. Webster (Ed), Linguistic Studies of Text and Discourse. Volume 2 in the Collected Works of M. A. K. Halliday. London and New York: Continuum. Halliday, M. A. K. 1985/89. Part A. In Halliday and Hasan 1985/89. Halliday, M. A. K. 1992[2003]. Systemic Grammar and the Concept of a “Science of Language”. In J. J. Webster (Ed), On Language and Linguistics: Volume 3 in the Collected Works of M. A. K. Halliday (pp. 199-212). London: Continuum. Halliday. MA.K. 2005[1995]. Computing meanings: Some Reflections on Past Experience and Present Prospects. In J.J. Webster (Ed) Computational and Quantitative Studies. Volume 6 in the Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday. London and New York: Continuum. pp239--267. Halliday, M. A. K. 2003. On the architecture of human language. In J.J. Webster (Ed), On Linguistics and Language. Volume 3 in Halliday's Collected Works. London and New York: Continuum. Halliday, M. A. K. 2001 [2003]. Is the grammar neutral? Is the grammarian neutral? In J.J. Webster (Ed), On Language and Linguistics. Volume 3 in the Collected Works of M. A. K. Halliday. London and New York: Continuum. Halliday, M.A.K. 2010. Language evolving: some systemic functional reflections on the history of meaning. Written version of plenary talk at ISFC 2010 at the University of British Columbia. Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, Ruqaiya. 1976. Cohesion in English. London: Longman. Halliday, M.A.K. and Hasan, Ruqaiya. 1985/89. Language, context, and text: Aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective. Oxford/Geelong: OUP/Deakin University Press. Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. 2004. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. Third Edition. London: Arnold. Halliday, M. A. K., McIntosh, Andrew., & Stevens, Peter. 1964[2007]. The users and uses of language. In Webster, J.J. (Ed) Language and Society. Volume 10 in the Collected Works of M.A.K. Halliday. London and New York: Continuum. pp. 5--37. Hartley, John. 1982. Understanding News. London and New York: Metheun. Hasan, Ruqaiya. nd. Cohesive Categories. Manuscript. Hasan, Ruqaiya. 1984. Coherence and cohesive harmony. In J. Flood (Ed), Understanding Reading Comprehension (pp. 181-221). Newark, Del.: IRA. Halliday, M. A. K. 1985/89. Part A. In Halliday and Hasan 1985/89. Hasan, Ruqaiya. 1995. The conception of context in text. In Peter H. Fries & Michael J. Gregory (Eds) Discourse in Society: Systemic Functional Perspectives. Meaning and Choice in Language: Studies for Michael Halliday. Advances in Discourse Processes Vol L. 183-283. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Hasan, Ruqaiya. 1996. Semantic networks: a tool for the analysis of meaning. In Carmel Cloran, David Butt & Geoff Williams (Eds), Ways of Saying, Ways of Meaning: Selected papers of Ruqaiya Hasan. London: Cassell. Hasan, Ruqaiya. 1999. Speaking with reference to context. In Mohsen Ghadessy (Ed) Text and Context in Functional Linguistics: Systemic Perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Hasan, Ruqaiya. 2004. Analysing Discursive Variation. In Lynne Young and Claire Harrison (Eds) Systemic Functional Linguistics and Critical Discourse Analysis: Studies in Social Change. London and New York: Continuum. pp15-52. Page 16 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Hasan, Ruqaiya. 2009a. The Place of Context in a Systemic Functional Model. In M. A. K. Halliday & J.J. Webster (Eds). Continuum Companion to Systemic Functional Linguistics. London and New York: Continuum. Hasan, Ruqaiya. 2009b. Wanted: a theory for integrated sociolinguistics. In Semantic Variation: Meaning in society and sociolinguistics. Volume 2 in the Collected Works of Ruqaiya Hasan. J.J. Webster (Ed). London: Equinox. Hasan, Ruqaiya. in press. Linguistic sign and the science of linguistics: the foundation of applicability. Hasan, Ruqaiya. forthcoming. Unity in Discourse: Texture and Structure. Volume 6 in the Collected Works of Ruqaiya Hasan. J.J. Webster (Ed). London: Equinox. Hasan, Ruqaiya, Lukin, Annabelle, Wu, Canzhong. in prep. Reflections on Space: homonymy, homophony, metaphor, or …? Herman, Edward. & Chomsky, Noam. 1988 [2002]. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, New York, Pantheon Books. Lukin, Annabelle. 2003. Examining poetry: a corpus based enquiry into literary criticism. Unpublished Ph.D. Macquarie University, Sydney. Lukin, Annabelle. 2012. Journalism, ideology and linguistics: the paradox of Chomsky’s linguistic legacy and his ‘propaganda model’. Published online first, Journalism: theory practice critique, April, 2012: http://jou.sagepub.com/content/early/2012/04/12/1464884912442333 Lukin, Annabelle. in press a. The meanings of ‘war’: from lexis to context. Journal of Language and Politics. Lukin, Annabelle. in press a. Creating a parallel universe: mode and the textual function in the study of one news story. In Wendy Bowcher and Brad Smith (Eds). Recent Studies in Systemic Phonology. London: Equinox. Martin, J.R. 1992. English Text: System and Structure. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. 1993. Register in the round. In M. Ghadessy (Ed.), Register analysis. Theory and practice. London: Pinter. Matthiessen, C.M.I.M., Teruya, K. and Wu, C. 2008. Multilingual Studies as a Multi-dimensional Space of Interconnected Language Studies. In J.J. Webster (Ed) Meaning in Context: Implementing Intelligent Applications of Language Studies. London and New York: Continuum. pp 146--220. Matthiessen, C.M.I.M. in press. Systemic Functional Linguistics as appliable linguistics: social accountability and critical approaches. DELTA. Otterman, Michael, Hil, Richard, with Wilson, Paul. 2010. Erasing Iraq: The Human Cost of Carnage, Pluto Press, in association with the Plumbing Trades Employee Union of Australia. Robinson, Piers, Goddard, Peter, Parry, Katy & Murray, Craig. 2009. Testing Models of Media Performance in Wartime: UK TV News and the 2003 Invasion of Iraq, Journal of Communication, 59 (2009) pp 534 – 563. Stiglitz, Joseph & Bilmes, Linda. 2008. The Three Trillion Dollar War. Allen Lane. Van Dijk, Teun. 2008. Discourse and Context: A sociocognitive approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Page 17 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Appendices Appendix 1.1. Text 1 “Scooby in a scrape” Scooby in a scrape: rescue op to save him from cave GEORGINA ROBINSON, September 10, 2009 http://www.smh.com.au/national/scooby-in-a-scrape-rescue-op-to-save-him-fromcave-20090910-fi1x.html 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. Scooby in a scrape Rescue op to save him from cave A crew of six rescuers are today trying to coax a tiny, deaf and ageing dog out of a cave in the NSW Hunter Valley. Scooby, an eight-year-old Cavalier King Charles spaniel, has been trapped since Sunday under a group of large boulders on his owner's 20-hectare property at Sweetmans Creek. ‘‘He chased something up or ran up a small cavity under a set of boulders and he just didn’t come back out,’’ RSPCA Inspector Matt French said. ‘‘There’s no reason [[he can’t walk out]] but we’re just a little concerned, given his age, he may be a little bit dehydrated and confused.’’ RSPCA officers have been working since Tuesday to free Scooby. A specialist NSW Fire Brigades rescue unit from Sydney travelled there yesterday, managing to send down a small camera and open up a passage for the dog so he could walk out again. ‘‘We got very, very close to him but we lost the light late yesterday afternoon,’’ Inspector French said. ‘‘We got food and water to him though. ‘‘He seems fine, he’s bright and alert, he’s standing up and ^HE’S moving around. ‘‘When we were in there trying to widen the tunnel we could hear [[him snoring]] so he obviously laid down for a sleep.’’ Inspector French said Scooby licked the camera when it reached him. He could even indulge in his favourite hobby from the darkened nook. ‘‘There’s a few flies [[that hang around him]] and he’s trying to eat the flies, which is one of his favourite pastimes,’’ he said. ‘‘Hopefully we’ll get him out in the next couple of hours.’’ Page 18 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Appendix 1.2: Identity chains in Scooby text 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 IC1 Scooby him a tiny, deaf and ageing dog Scooby, an eight-yearold Cavalier King Charles spaniel; his He he he he IC2 IC3 IC5 we RSPCA officers (RSPCA officers) A specialist NSW Fire Brigade Unit rescue unit 16 18 19 20 he him he he he ^HE there a small camera (rescue unit) we we a passage Inspector French we we (we) 28 29 him he 30 31 Scooby him 32 33 34 35 36 He; his him he his him Page 19 9/02/16 IC8 RSPCA Inspector Matt French Scooby the dog IC7 Sweetman’s Creek his he 17 IC6 rescuers 15 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 IC4 we the tunnel Inspector French a small camera it he we PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Appendix 1.3: Chain interaction in Scooby text. 1 2 3 4 Scooby scrape save coax cave cave 5 him a tiny, deaf and ageing dog Scooby trapped large boulders 6 He ^CAVITY chased 7 ^HE cavity ran up 8 he 9 10 11 12 he [of cave] come back walk out today NSW Hunter Valley since Sunday Sweetman’s Creek we be he 13 14 rescuers Scooby 15 16 17 the dog 18 he be work RSPCA officers free (RSPCA officers) send down (rescue unit) (rescue unit) open up Page 20 9/02/16 passage [of cave] since Tuesda y walk out concerned dehydrated confused PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION 19 him got close to we 20 21 him got food/water we 22 he 23 he 24 he 25 ^HE 26 27 see ms be fine bright alert standing up moving around widen tunnel we (we) be 28 29 him he 30 Scooby licked He; his indulge 31 32 33 34 35 he his 36 him we hear snoring laid down favourite hobby favourite pastimes get <> out Page 21 9/02/16 [of cave] we hours flies (flies) eat (eating) PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Page 22 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Appendix 2.1: Text 2 ABC TV 7pm news, broadcast March 20th, 2003. Bulletin preview/overview 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Tonight the war against Iraq begins with Baghdad under attack President bush promises to disarm Saddam and free the Iraqi people “this will not be a campaign of half measures, and we will accept no outcome but victory” welcome to a special edition of ABC news. The second gulf war has begun. Just before dawn, Baghdad time, the air raid sirens went off as a series of explosions rocked the city. This initial strike was limited. The main attack is expected within 12 to 24 hours. Here’s [[how the day developed]]: Within 90 minutes of the deadline passing [[for Saddam Hussein to leave Iraq]], American bombers attacked military targets around Baghdad. 14 President George W. Bush promised a broad and concerted campaign [[to disarm Iraq. ]] 15 Prime Minister John Howard said Australian FA-18 Hornets were already operating over Iraq. 16 And in a televised speech Saddam Hussein accused the United States of crimes against humanity. First report of the bulletin, following directly from preview/overview above. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 The opening shots of the war came as a surprise. Unlike the massive air attack of 1991, the US launched a limited series of missile strikes apparently targeting Saddam Hussein and other Iraqi leaders. US president George W. Bush warned against assumptions of an easy triumph, and ^US PRESIDENT GWB vowed there would be no result but a Coalition victory. The ABC's Lisa Millar begins our coverage from Washington. The first blasts were heard just before dawn in the south east of Baghdad. Cruise missiles were launched from ships in the Persian Gulf, and precision guided bombs dropped on a small number of specific targets. It was not the massive air campaign [[which was expected to launch this war]]. As anti-aircraft fire and explosions were heard across Iraq's capital, the White House gave short notice of the American president's plans [[to speak to the nation]]. My fellow citizens, at this hour, American and Coalition forces are in the early stages of military operations [[to disarm Iraq, to free its people, and to defend the world from grave danger]]. His speech came two hours after the end of the 48 hour deadline [[he'd given Saddam Hussein]] [[to leave the country]]. Now that conflict has come, the only way [[to limit its duration]] is [[to apply decisive force]]. And I assure you, this will not be a campaign of half measures, and we will accept no outcome, but victory. President Bush spent four hours with his top advisors this evening, who convinced him there was no time [[to waste]]. Officials say they believed they had Iraqi leaders in their sights, and Saddam Hussein may have been among them. They had to strike. They aren't saying how successful the bombing was. In New York, Iraq's ambassador to the United Nations said he would continue to urge security council members to help his country. I have just to tell them, the international community, that the war has started, this is against the charter and this is the violation of international law. President Bush says the military campaign is now supported by 35 nations around the world, although only three, the US, the UK and Australia are providing troops. And << the US plan to use the full might of its military <<while they would make every effort [[to spare Iraqi civilians]],>> Lisa Millar, ABC news, Washington. Page 23 9/02/16 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Appendix 2.2 Identity Chains in "Iraq War" text. Notes: tokens with asterisk are exophoric; items preceded by a question mark have been assigned provisionally to an identity chain, but there is ambiguity in the relations. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 IC1 IC2 the war against Iraq Iraq IC3 IC4 IC5 IC6 Bush Saddam IC7 IC8 IC9 IC10 IC12 Baghdad the Iraqi people *this *we the 2nd Gulf War 8 9 the city a series of explosions 10 ?This initial strike 11 12 13 Iraq 14 15 16 1 IC11 Baghdad Iraq Saddam Hussein Bush Iraq Saddam Hussein the United States the war 2 the US 3 4 5 6 7 8 Page 24 9/02/16 the opening shots of the war a limited series of missile strikes US President George W Bush (Bush) Baghdad Saddam Hussein the first blasts Iraqi leaders IC13 IC14 IC15 IC16 IC17 IC18 PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION 9 10 11 this war It* Iraq's capital 12 13 the American president my Iraq its 14 explosions the country his he the White House its people the nation my fellow citizens military operations the world Saddam Hussein 15 16 conflict its 17 18 19 I we President Bush his him 20 21 22 *this you *we advisors Saddam Hussein 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 who they their Iraqi leaders them they they ?the bombing Iraq country Iraq's ambassador he his I the war this this President Bush ?the military campaign 30 31 32 33 Page 25 9/02/16 Iraqi civilians the US the US its they the world PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Appendix 2.3 Schematic representation (not all tokens can be shown) of chain interaction in "Iraq War" text; bold arrows indicate interaction between units within the clause; dotted arrows indicate relations internal to the nominal group Page 26 9/02/16