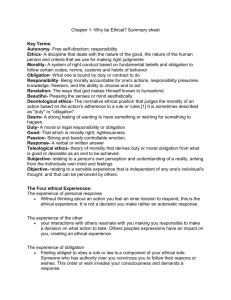

Chapter 1 Summary Note: What Is Ethics What Is Ethics? A set of

advertisement

Chapter 1 Summary Note: What Is Ethics What Is Ethics? o A set of do’s and don'ts imposed by authority that may be treated as an obligation or duty o May be presented as rules or as a moral code in society o Involves morals and what we believe to be right or wrong The Ethical Experience: Four Ways Of Finding The Ethical In You 1. The Scream The experience of personal response When someone needs help you immediately want to help them because you are aware of your responsibility to that person This “scream” for help urges you not to think, but to act This is knows as the “Ethical Response” 2. The Beggar The experience of the other According to philosopher Emmanuel Levinas said that when we are face to face with another, something happens to us That person is known as the “other” These face to face encounters are ethical as they remind us of our responsibility to others In these encounters the “other’s” face has taken you hostage and gave you responsibility Ex. when a homeless person asks you for money you often walk away, but as you walk away you think about your decision to give or not to give. This person stays with you and makes you feel responsibility 3. I Have To The experience of obligation Ethical senses are turned on when you are told to do something The feeling of being obligated to do something is your ethical side This order has invaded your consciousness and demands a response The thing you are obligated to do becomes the right thing to do and is therefore The ethical thing to do Ex. Your parents give you a curfew 4.This Isn’t Tolerable Experience of contrast The feeling you get when you see something unfair or unjust When unjust things occur you feel overwhelmed as that is not how you learned the world should be Humans only have a certain capacity for unjustly actions and once this capacity is reached we react/ respond This reaction is your ethical side coming to life Defining Ethics From philosophers, we have inherited different theories that help explain to us ethical experiences, and to translate them into a practical way of living What one person considers a duty cannot be said for everyone at all times Ethics is about the goodness of human life Aristotle, Kant, and Levinas were 3 of the greatest ethical thinkers Ethics vs. Morality Ethics means good character Morality means customs or rules Ethics is concerned with the good that humans want (i.e. happiness and freedom) Morality is concerned with the ways in which humans can attain this good Ethics guides morality and gives us a vision to our actions Morality shows us the rules we must follow to reach the good we seek Aristotle (384-322 BC): o Aristotle was born in Stagira and introduced to anatomy and medical practices at a young age by his father. o When Aristotle was seventeen, his parents died. Thus, he moved to Athens and continued his education at Plato’s academy. o Plato saw promise and great intellectual abilities in Aristotle. Consequently, he took Aristotle under his wing. o Although they both approached philosophy differently— Plato focused on abstraction and the world of ideas, while he thrived on contemplation. Whereas, Aristotle focused on the natural world and human experiences and thrived on observation and classification— Aristotle greatly respected Plato and remained under his guidance for twenty years. o Following Plato’s death in 347 BC, Aristotle left Athens for the Eastern Aegean. o There Aristotle became political advisor to Hermeias and later married his niece. However, they were forced to flee after Hermeias was executed for offending the king. o Aristotle was invited to tutor a young boy named Alexander, the son of his childhood friend. o Alexander proved to be a good student and was later titled ‘Alexander the Great’. Hi armies conquered and controlled a large portion of Asia. o Under Alexander’s sponsorship, Aristotle founded his own school where he wrote extensively on a wide variety of subjects. o Following Alexander’s death in 323 BC, charges were brought against Aristotle for not respecting the gods of the state. o In attempt to preserve his life, Aristotle fled. However, he died only a year later. Aristotle’s Teleological Ethics In the thirteenth century, Thomas Aquinas rediscovered Aristotle, thus assuring Aristotle a place in the development of Catholic ethical theory. The Pursuit of Happiness Aristotle believed that society shaped a persons life through its principles and influences. He did not associate pleasure with happiness. In fact, he believed that pleasure was momentary, while happiness was awarded to those who did well in typical tasks. Therefore, a ‘good person’ is deserving of happiness. Teleology Aristotle believed that everything we do is aimed towards the good. According to Aristotle, we are intended to be rational and our greatest capacity is our intelligence. Moreover, we must develop this capacity. We must equally develop our character and base our actions on reasoning. “The good person is one whose actions as a rule are solidly based on excellent reasoning and who spends a great amount of time thinking”. Human Excellence Based on Aristotle’s beliefs, virtues are habits that one develops in accordance to what they believe is good— It means allowing reason to guide one’s actions. Aristotle believed that a good person would use reason to control desire. Accordingly, habits are formed through the continuous choosing to do virtuous things. The Mean Aristotle understood the importance of maintaining balance and saw necessity in moderation. “To be courageous is to avoid some but not all dangers; to be polite is to be courteous in some but not in all situations”. Furthermore, this moral was generated by the belief that moral qualities could be destroyed by defect or by excess. The mean preservers all. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) o Emmanuel Kant was born in northeast Germany, where he was raised in a religious household stricken by poverty. o His parents were protestant, who lived severe puritanical lives. Meaning that they believed in personal devotion, bible reading and the universal priesthood of all the faithful. o Kant studied at a local university while working as a private tutor and later a private teacher at the university. o At the age of forty-six, he was hired as a professor of logic and metaphysics. Throughout the following years, Kant wrote many books (most of which were hard to understand). Theoretical Reason Theoretical reason is an area by which we come to know how the laws of nature and the laws of cause and effect influence human behavior. Kant’s main focus was how we come to know things. Practical Reason Practical reason denotes the moral (i.e. conscious choice based on principle) reasoning that guides human behavior. Kant’s Ethics Kant believed that the good is the aim of a moral life. Furthermore, he approached the attainment of ‘the good’ through ethical reasoning; where ethics present practical certainty, as opposed to rational certainty. According to Kant, practicality has three areas: God (when one cannot achieve supreme goodness on their own, God is there to aid them), Freedom (one must be free to do anything in order to achieve the supreme good) and immortality (where there is a life beyond in which one can achieve the supreme good, as it is impossible to achieve fully in one’s lifetime). The Good Will Kant believed that in life, what is most important is to have a good will— the will to do our duty for no other reason that that it is our duty. Thus, ‘will’ is central. Impulses and desire can sometimes shadow our duties. Moreover, will allows us to overcome temptation and act according to our duty. “Moral worth is measured not by the results of one’s actions, but by the motive behind them”. Kant’s Use of Moral Maxims Moral living requires reasoning, while duty is determined by objective principles (ethical maxim). An ethical maxim is an action in which any rational person would perform under objective principle. The person as an end, not a means Kant strongly believed that people should never be threated only as a means. Thus, regardless of classification, everyone must be respected. He wanted everyone to act rationally. Not out of principal or personal benefit. Emmanuel Levinas (1905-1995): An ethics of the face o Marked by the tragedies of the twentieth century (Particularly the Holocaust or the Shoah) o Raised by Jewish parents in Kaunas, Lithuania. At 17, moved to France to begin his studies in philosophy and in 1928 he continued his studies in Freiburg, Germany o Began to experienced a big between western philosophy and his own deeply rooted Jewish faith The sameness of things He grouped everything under a unity, called “Being”, to overcome all diversity and differences He declared that Westerners were said to think of a unified totality where difference is reduced to being accidental (meaning “not essential” because it changes in every individual) The singularity of things He stated that the Hebrew tradition gloried in the singular. Singularity gives each thing its identity. He could not find anything that could hold all these singularities together in some kind of unity, which contrasted the Western notion of “totality” with the Hebrew notion of “infinity” His whole family died in the Holocaust except for his wife and daughter who kept hidden in a monastery in France until the end of the war, unable to talk to him. He had a tough experience in World War II, which heightened his awareness of his Jewish roots because his entire family died during the Holocaust. At the age of 55, he completed his doctoral thesis, Totality and Infinity. The Good is infinite Levinas’s philosophy as a whole is ethical. He is in search of the good. The Good goes beyond the Being. Being seeks to name what things have in common when you take away all the differences. Levinas believes that it is dangerous because it takes away the uniqueness of each person or thing. The Good is interested, not in what is common among things but in what is absolutely unique about each person or thing. Levinas calls these unique things and persons “traces” of the Good, or God. No object is identical to God, or the Good. A trace says that God was there but is no longer there. The face as witness of the Good The face is the part of the human body, in which we make the most direct contact. Levinas called a face-to-face experience that touched you deeply a “thrill of astonishment” because these experiences are the most original moment of meaning In the eyes of the other, you cannot be anything but your true self. The other asks to not compare their face it to any other but their own. This person’s face is a “No”: a refusal to let you reduce the face or to deny the face in its uniqueness. Levinas translated this “No” as “You shall not murder.” You are not to take the otherness away. The face is an authority, “highness, holiness, and divinity.” The face is ethical The face that levinas is referring to is not an authority figure The other is a stranger. One whose very existence is threatened, one with no economic stability or security, one who is socially marginalized and without rights. At this point, Levinas says that the face becomes ethical. Recognizing the other’s depth of misery or humility is what makes the command or appeal of the face ethical. The face of the stranger demands that you recognize it and provide it hospitality although it cannot force you to do anything. The face makes you responsible by making you aware that you are not as innocent as you thought you were, but as someone who is concerned, mostly about yourself. The face is a trace of God who has already passed by Made responsible by the face The face makes us responsible The search for the good ends God’s touch will always be indirect. God touches us through the face of the other. God refuses to appear, leaving only a trace in the face of the other, retreating to make room for the Other.