Sub-Groups report – Proof of intra-EU supplies

advertisement

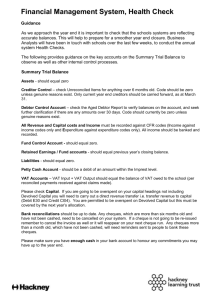

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL TAXATION AND CUSTOMS UNION Indirect Taxation and Tax administration Value Added Tax 7th VAT Expert Group meeting – 6 February 2014 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – EN Brussels, 13 January 2014 VAT EXPERT GROUP VEG NO 027 Option 1B - Sub-Groups report – Proof of intra-EU supplies Commission européenne, 1049 Bruxelles / Europese Commissie, 1049 Brussel – Belgium – Tel.: +32 2 299 11 11. taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL TAXATION AND CUSTOMS UNION Indirect Taxation and Tax administration Tax administration and fight against tax fraud Brussels, 10 January 2014 [Annex to D-47090] EU VAT FORUM N° 3/9 (final) WORKING DOCUMENT FOR OFFICAL USE ONLY EU VAT FORUM Report to the Group on the future of VAT and the VAT expert group 1. INTRODUCTION AND MANDATE In discussions within the Group on the future of VAT and the VAT expert group,1 Member States wanted to ascertain whether it is possible to improve the functioning of the current VAT “transitional” system with regard to intra-EU supplies. As a consequence, the EU VAT Forum set up a specific working group to consider the proof of despatch or transport to another EU Member State (‘proof’) required to VAT exempt intra-EU supplies of goods.2 The aim of this sub-group was to analyse best practices and the possibilities for cooperation in order to improve the functioning of the current VAT system. 13 Member States3 and representatives from 9 business organisations4 participated in the working group. Based on an understanding of business models and different intra-EU scenarios, which correspond to the current practices of Member States regarding the proof required for intra-EU supplies, the sub-group sought to identify possible ways to be more efficient on both sides. It was agreed that the sub-group should report back its findings to the EU VAT Forum to enable the EU VAT Forum to issue recommendations in this field in time for the next meetings of the Group on the Future of VAT and the VAT Expert group. 1 2 3 4 Discussions based on working document GFV 22 - Group on the future of VAT + VAT expert Group. As set down in article 138 of Directive 2006/112/EC. BE, BG, DK,DE,IE,ES,EE,IT, LT,AT,HU,PL,PT,NL,SK. Business Europe, CBE, CFE, EEA, EPMF, FEE, IVA, Siemens, TEI. 2/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 2. WORKING METHOD Three meetings of the sub-group took place5. In addition, two questionnaires6 were sent to all participants, to enable members of the sub-group to gain an understanding of current practices in Member States. Business members also shared information on the commercial documentation which could be provided in different scenarios as proof of the despatch or transport of goods in case of an intra-EU supply. 2.1. Information sharing Business and Member States participants agreed to base their discussions on a set of business models corresponding to different scenarios for B2B intra-EU supplies of goods, which varied from the simplest (two party transactions) to the more complex supply chains. The aim was to identify those situations where properly documenting intra-EU supplies were likely to be more difficult. Business also provided the group with a detailed end to end process map of internal controls applied to manage risk, and the related documents produced, when carrying out an intra-EU supply of goods. 2.2. Identification of the most difficult situations to be documented Among the different scenarios, it was considered that the supplier’s obligation to provide evidence of an intra-EU supply of goods was straightforward in transactions involving two parties where transportation of the goods is handled by a third party. However, two other scenarios of intra-EU supplies were considered to be problematic, as follows: - when the supplier, or the customer, transports the goods using his own means of transport; and - when goods are sold “ex works”. In both cases, tax authorities require proof that the goods have physically left the territory of the Member State of the supplier7 to be despatched or transported to another EU Member State. The group did not discuss in depth the other condition necessary for the VAT exemption of intra-Community supplies (i.e. the customer’s status as a taxable person). However, the sub-group acknowledged that this issue was relevant to the wider issue of the prevention of fraud. In relation to the controls undertaken and documents generally available, the participants of the sub-group acknowledged that there were no substantial differences between SMEs’ and larger companies involved in intra-EU trade. The requirements of Tax authorities for businesses to provide proof are almost identical for both categories of enterprises. 5 31 July 2013, 4 October 2013 and 20 November 2013 . Note dated 19 June 2013 with reference taxud.c.4/HM/LV/tm (2013)2394405 and e-mail of 14/10/2013. 7 Article 138(1) of Directive 2006/112/EC. 6 3/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 However, it was acknowledged that SME’s often find it more challenging to gain access to appropriate information and, in consequence, have less of an understanding of their legal obligations. 2.3. Appointment of rapporteurs Two rapporteurs (one from the tax administrations and one from the Business members) were designated to summarize the discussions and report to the EU VAT Forum. It was agreed that the report should be circulated among the members of the sub-group by the secretariat for comments and suggestions, so that it can be adopted by consensus by the sub-group. If it is not possible to finalise the report, the remaining issues could be discussed at the EU VAT Forum plenary meeting. 3. STATE OF PLAY 3.1. General remarks The efficient operation of the internal market is essential for business in order to create growth and employment. The tax environment in which businesses operate, provided by tax authorities, can have a direct impact on competition between companies, as well as between Member States. Therefore, the principles of fairness, tax neutrality, legal certainty, legitimate confidence and proportionality must be applied and respected by tax authorities (as well as judges). At the same time tax authorities are under considerable pressure to recover VAT more efficiently and to ensure that all taxpayers are treated fairly and equally, which implies that fraud has to be combated even more effectively. In recent years, many Court cases at the EU level in the field of VAT have concerned the issue of fraud. Carousel fraud and substantial disruption to certain markets by fraudulent operators have been reported. Consequently, the fight against tax fraud is currently a major issue at both national and EU level. However, combating fraud should not lead us to overlook the fact that the vast majority of businesses comply with the rules. In considering whether the VAT exemption should be applied to the intra-EU supply of goods, the business representatives view this as comprising three elements as follows: i. whether, in principle, the transaction falls within the scope of the legislation; ii. whether the supplier has carried out all reasonable steps to verify the good faith/ standing of his customer (the ‘knowledge test’); and iii. whether the supplier holds the required proof that the goods have left the Member State of dispatch, to be delivered/transported to another EU Member state. Business representatives believe that the use of documentation (either in terms of a different format, or additional information) is not an effective means to combat fraud as, 4/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 in practice, the fraudsters will hold, or provide, perfect documentation (which does not affect the possibility for the Member States to ask for documentary evidence). Preferably, the detection and prevention of fraud, which is an issue for both legitimate business and tax authorities, needs to be dealt with at an earlier stage in the process (i.e. the point at which goods are being dispatched and invoiced is too late). For example, although this is an issue which the business participants believe should be considered by the proposed subgroup on fraud, effective controls by a business as part of the knowledge test could prevent fraud. Consequently, in considering the issue of proof, the sub-group has focussed on situations where fraud is not present. In any event, it is observed in practice that holding the required proof (in whatever format) did not enable the supplier to VAT exempt its supply if the business failed the “knowledge test”. Consequently, the distinction to be made between legitimate business and fraudsters is a major issue for both parties and should be further explored. 3.2. Means of proof, documentation, setting the scene 3.2.1. Diversity of documentation The answers to the questionnaire reflected different approaches in Member States. Some Member States are less demanding than others regarding the means of proof of an intraEU supply and the documentation that has to be provided in this respect, accepting various forms of alternative evidence. However, in most cases there is no single document which would be sufficient but a number of different types and formats, which may or may not be listed in national legislation, or alternatively used in practice. For instance8: commercial documents relating to contractual commitments, an invoice mentioning the fact that it relates to an exempt intra-EU supply; a document signed by the purchaser (or authorized person) acknowledging the receipt of the goods in the other Member State; a payment document proving that the purchaser has paid for the goods received, proof that the transaction has been correctly reported in the VAT returns and in the intra-EU sales listing of the supplier; proof of the VAT registration of the purchaser in another Member State at the time of the supply; the Intrastat listing; bank documents proving payment by the customer; etc… 3.2.2. Documentation concerning the transport of the goods outside the territory of the Member State of the supply into another Member State Several documents may be requested by tax authorities, depending on national legislation and practice. For instance9: bills of lading; airway bills; a signed CMR; consignment note; the invoice from the carrier, as well as the evidence of payment of the carrier invoice; a receipt issued by the customer; order document; delivery docket; supplier’s invoice; evidence of transfer of foreign currency for payment; drivers logs (tachograph); diesel records; an insurance policy with regard to the international transport of the goods; also reliable third party documents; verification (by an authority, or a notary) of the delivery to, or the arrival in, another Member State; a storage receipt issued in the Member State of destination (or the storage contract) mentioning the goods specified according to types, quantity, value and quantities; a certificate issued by a professional body of the Member 8 9 This list corresponds to the answers given by the Member States to the two questionnaires. It is not exhaustive and contains no ranking. See foot note 8 above. 5/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 State of destination (for example: chamber of commerce or industry); a minute, or other certification, of the escrow account of a solicitor; etc… 3.2.3. Media and format of the documents In most cases, Member States will accept the documents provided as proof in any available format. Only a few Member States require the document to be provided through an electronic portal. However, in the event of an audit, Member States require “readable” documents be made available to the tax authorities. Therefore, it is for taxpayers to ensure that documentation is accessible either electronically, or physically, to the tax authorities until the end of the limitation period laid down in the national legislation. In the context of intra-EU trade, some Member States have now issued national forms which may be used by the supplier in certain circumstances (e.g. ex-works, and goods transported by the supplier or the purchaser without a third party). In one case, the tax authority concerned underlined that these forms are optional and that they constitute nonexclusive means of proof. They are meant to help the supplier to provide evidence. Some tax authorities expressed an interest in this initiative. From a business perspective, it was acknowledged that such forms were helpful in providing certainty to the supplier in certain scenarios, but that care needed to be taken to avoid such documents becoming mandatory in practice (e.g. in the event of an audit). Accordingly, the ability to provide alternative proof should be available to suppliers. 3.2.4. Time to provide the documentation to the tax authorities There are also differences between the Member states as to when the documentation should be provided. For some Member States, in principle, all evidence must be provided at the time the supply is carried out. In other Member States, part of the proof can be provided later (e.g. the VAT number which was not known at the time of carrying out the supply). In their reply to the first questionnaire, some Member States took the view that complete proof should exist at the moment of an audit. One Member State observed that, as tax authorities must have full evidence that the conditions were fulfilled at the time of delivery, the original signature of the entrepreneur, or a person acting on his behalf, who receives goods must be given at the time of delivery of the goods. A later confirmation, or a qualified statement, would not be possible in that case. On this point, the Commission drew the sub-group members’ attention to the well-established case law of the ECJ (in particular the Collée judgment). From the perspective of business representatives any requirement that full information must be available at the time of delivery is simply not practical. A supplier has a legitimate expectation that he should have certainty as to the VAT treatment of a supply at the time an invoice is issued (which will often occur before the delivery is physically made, or completed) and be able to VAT exempt a supply, even if documentary proof that goods have left the Member State of dispatch is received later. 3.2.5. Authentication of the documents Some Member States have additional requirements regarding the necessity to have documents signed. Specifically, these include a requirement for an original signature from the entrepreneur, or a person acting on his behalf, who receives goods. In the case of 6/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 signatures, providing them subsequently is not accepted. On this point, the Commission informed sub-group members of a preliminary request currently pending before the ECJ (C-492/13, Traum). Some Member States have now issued a new national form which can (or should) be used by the supplier, which can assist suppliers in providing proof (e.g. where the supplier, or customer uses their own means of transport). Tax authorities concerned see these as a useful additional source of information (e.g. because they contain a delivery address, vehicle type and registration number) and tax auditors could expect that these forms are part of the body of documents that taxpayers should be able to provide in the course of an audit. From their point of view, these forms may help the taxpayers who don’t have any other available means, to establish the despatch or transport of the goods from the Member State of supply to another Member State. However, from a business perspective, any requirement to provide additional information in respect of a supply (e.g. place of delivery, vehicle registration number, identity of the driver) could only ever identify a potential fraud after the event and does not assist in the prevention of fraud, or prevent a loss of tax if the supplier has taken all reasonable steps such that it passes the ‘knowledge test’. 3.2.6. Proof value of the documents The answers from business to the questionnaire have highlighted an important difference, compared to tax authorities, in the status and the commercial weight placed on the receipt of payment for a supply from a customer. Business would stress that this fact is a key element in their business process giving a tangible indication that the intra-EU supply of goods has taken place according to the contract agreed between the supplier and his customer. Of course, as part of the normal commercial process, full or part payments can and are sometimes requested from new or existing customers in advance of the delivery of goods. In such cases, business accepted that receipt of a payment could not be used as part of the proof that goods have been dispatched from a Member State. However, Member States pointed out that in the current state of the legislation, payment as such is not on its own adequate to document the physical movement of the goods properly as required by Article 138(1) of directive 2006/112. Some Member States take the view that no single document is sufficient to prove an intra-EU movement of goods and that it is essential to consider all the commercial documentation available. In such cases, documentation from a third party (e.g. transport documents, such as a CMR) are viewed as having more weight. 4. LEGAL ISSUES 4.1. General remarks Given the absence of any specific provision in the VAT Directive, Member States are free to ask for documents to support the right to exempt intra-EU supplies, in accordance with Art. 131 of that directive, but bearing in mind the tax neutrality and proportionality principles. 7/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 Business representatives insisted that the level of demands from tax authorities to document intra-EU trade should not systematically be upgraded because of recent fraud cases. One reason for not escalating this is that very few fraud cases were discovered on the basis of missing documents. It was generally acknowledged that fraudsters usually provide almost impeccable documentation and are able to provide all sorts of documentation at short notice. Nevertheless, in recent years, it seems that the line of reasoning developed by the Court of Justice of the European Union in situations of fraudulent chain transactions, is also now being used in a broader context where errors, or failure to comply with formal obligations, have been identified (see case C- 284/11, 12 July 2012, para. 74). A number of requests for proof by tax authorities seem to be driven more by fears of a worst case scenario rather than by a risk analysis strategy. Precisely with the aim of fighting fraud, one Member State has made recent legislative changes whereby the supplier is now required to document not only the transport of goods outside the territory but also the fact that the goods have reached their destination10. Another Member State is currently considering whether to introduce a requirement that, where the buyer pays in cash, or with debit or credit card, the person collecting the goods will be required to present proof of identity to the seller. If the person collecting the goods is not the owner of the business buying the goods then the person will have to demonstrate that they have the legal power to represent the buyer, to the seller. Accordingly, it is clear that paper documents are still important to many Member States. Furthermore, some Member States impose conditions as to the authenticity of the signature of the person acquiring the goods. Setting aside the question of the proportionality of such demands (see preliminary ruling request in case C-492/13), the EU digital agenda should be considered. However, aspects relating to the EU digital agenda were not evoked by the sub-group participants. 4.2. Guiding principles, Internal market context – Free movement of goods - ECJ Case law “The position of economic operators should not be less favourable than it was prior to the abolition of frontier checks between the members states, because such a result would run counter to the purpose of the internal market which is intended to facilitate trade between them. In the absence of intra-Community frontiers, the transitional intra-Community supplies schemes should not be more cumbersome for economic operators than before. Whilst it is true that the regime governing intra-Community trade has become more open to fraud, the fact remains that the requirement for proof established by the Member States must comply with the fundamental freedoms established by the EC treaty, such as, in particular, the free movement of goods. 10 See C-430/09, Euro Tyre, para. 38 quoting C-409/04, Teleos, para. 67 “… once the supplier has fulfilled his obligations relating to the evidence of an intra-Community supply, where the contractual obligation to dispatch or transport the goods out of the Member State of supply has not been satisfied by the purchaser, it is the latter who should be held liable for the VAT in that Member State.” 8/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 Under Article 28(8) of the sixth Directive, the Member States may impose the obligations which they deem necessary for the correct collection of the tax and for the prevention of evasion, provided that such obligations do not, in trade between Member States, give rise to formalities connected with the crossing of frontiers.” (C-409/04 Teleos, paras. 62-64). 4.2.1. What should be documented with regard to intra-EU trade? “Apart from the requirements relating to the capacities of the taxable persons, to the transfer of the right to dispose of goods as owner and to the physical movement of the goods from one Member State to another no other conditions can be placed on the classification of a transaction as an intra-Community supply or acquisition of goods” (C-409/04 Teleos, para. 70). 4.2.2. Who should provide the evidence of the intra-EU supply? It is for the supplier of the goods to provide the proof that the conditions are met. “Once the supplier has fulfilled his obligations relating to the evidence of an intraCommunity supply, where the contractual obligation to dispatch or transport the goods out of the Member State of supply has not been satisfied by the purchaser, it is the latter who should be held liable for the VAT in that Member State. See Teleos case C-409/04 para. 67.”(C-184/05 Twoh para. 26). 4.2.3. How is this proof to be provided and the documents been assessed? In the Meilike judgment (C-262/09, 30 June 2011), the Court stresses that the assessment of the means of proof must not be conducted too formalistically (para 46) (direct taxation). “Transactions should be taxed taking into account their objective characteristics (see, in particular, Optigen and Others, paragraph 44, and Kittel and Recolta Recycling, paragraph 41). (…) since it is apparent from the order for reference that there is no dispute about the fact that an intra-Community supply was made, the principle of fiscal neutrality requires – as the Commission of the European Communities also correctly submits – that an exemption from VAT be allowed if the substantive requirements are satisfied, even if the taxable person has failed to comply with some of the formal requirements. The only exception is if non-compliance with such formal requirements would effectively prevent the production of conclusive evidence that the substantive requirements have been satisfied. However, that does not appear to be so in the main case”. (Case C-146/05 Collée, paras 30,31). “The first subparagraph of Article 28c(A)(a) of the Sixth Council Directive 77/388/EEC of 17 May 1977 ... must be interpreted as precluding the refusal by the tax authority of a Member State to allow an intra-Community supply – which actually took place – to be exempt from value added tax solely on the ground that the evidence of such a supply was not produced in good time” (C-146/05 Collée, first para of the operative part). 4.2.4. Good faith, proportionality “However, any sharing of the risk between the supplier and the tax authorities, following fraud committed by a third party, must be compatible with the principle of proportionality (Teleos and Others, paragraph 58). 9/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 “That will not be the case if a tax regime imposes the entire responsibility for the payment of VAT on suppliers, regardless of whether or not they were involved in the fraud committed by the purchaser (see, to that effect, Teleos and Others, paragraph 58). As the Advocate General has pointed out in point 45 of his Opinion, it would clearly be disproportionate to hold a taxable person liable for the shortfall in tax caused by fraudulent acts of third parties over which he has no influence whatsoever. Accordingly, the fact that the supplier acted in good faith, that he took every reasonable measure in his power and that his participation in fraud is excluded are important points in deciding whether that supplier can be obliged to account for the VAT after the event (see Teleos and Others, paragraph 66).” (Case C-271/06, Netto, judgment of 21.02.2008, paras. 23 to 25). It is for national authorities and national courts to decide whether the supplier has taken every reasonable measure in his power, or has exercised all due commercial care, when applying the principle of proportionality. The objective elements are to be weighted according to the merits of each case. But also when it comes to deciding whether an operator has acted in good faith, a subjective aspect comes into play. In cases such as ‘ex works’ sales, or 3-party transactions, this notion could be interpreted in a different way by tax authorities and national courts. Therefore, suppliers are put in a risky situation against which the sole real remedy for a supplier (within the current legal framework) is either not agreeing to the transaction, or trying to charge VAT of the Member state of the supply to the purchaser and for the latter to ask for a reimbursement of the VAT initially charged once adequate evidence is provided to the supplier. However, business representatives emphasised that the commercial reality is that a supplier is rarely, if ever, able to charge VAT on an intra-EU supply pending the receipt of acceptable proof from his customer that the goods have been despatched or transported out of the Member state of the supplier. The reality is that the customer will invariably refuse to pay the VAT element shown on an invoice with the result that the supplier is left with the VAT liability irrespective of whether he has passed the ‘knowledge test’ and despite a legitimate expectation that he should be able to VAT exempt the supply. At best this dilemma leaves the supplier with a cashflow cost and, at worst, means he bears the full risk of the VAT. In such cases, a business (especially an SME) might feel that their only option is to decline the transaction. 4.2.5. Legal certainty: when is a business on the safe side? The EUCJ stressed that: “...it would be contrary to the principle of legal certainty if a Member State which has laid down the conditions for the application of the exemption of supplies of goods for export to a destination outside the Community by prescribing, among other things, a list of the documents to be presented to the competent authorities, and which has accepted, initially, the documents presented by the supplier as evidence establishing entitlement to the exemption, could subsequently require that supplier to account for the VAT on that supply, where it transpires that, because of the purchaser’s fraud, of which the supplier had and could have had no knowledge, the conditions for the exemption were in fact not met (see, to that effect, Teleos and Others, paragraph 50).” (Netto C-271/06, paras 26, 27). 10/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 In several EUCJ cases (e.g. C-409/04, Teleos, para. 48; C-273/11, Mecsek Gabona, para. 39) it has been stressed, that the principle of legal certainty requires that taxable persons are informed about their tax obligations before concluding a transaction. 5. ROLE OF THE TAX AUTHORITIES, ADMINISTRATIVE COOPERATION If the supplier is not able to establish the existence of an intra-EU supply, there is no obligation for the tax authorities of the Member State of dispatch or transport to request information from the authorities of the destination Member State in order to assist the supplier (C-185/04 Twoh, paras. 28-38). However, neither this case law, nor the administrative cooperation channels and rules, prevent tax authorities from making use of data available to them in cases where a supplier was not able to document an intra-EU supply. Some Member States of the group acknowledged that a better use of administrative cooperation tools could be beneficial.11 Nevertheless, it should be borne in mind that most tax authorities do not have the necessary (human) resources to undertake such a process. 5.1. Role of third parties such as Transporters, shipping agents The sub-group did not deal with this item in depth given the short time frame available and the fact that, in the context of proof, ex-works supplies and arrangements involving ‘own transport’ were perceived to be more problematic. However, it might be important to assess if third parties such as transporters and shipping agents can play a larger role in giving trust and assurance and how this can influence the compliance costs compared to the benefits for business and for the tax authorities. 5.2. Special regime for ‘group’ companies None of the 11 Member States that have answered the questionnaire allow specific and/ or less-burdensome requirements for proof on intra-EU movement of goods between members of the same corporate group. Some members of the sub-group invoked the principle of equal treatment. However, where a risk analysis was being undertaken by a tax authority (or horizontal monitoring is applied ), the risk of fraud may be different between members of the same corporate group, or between parties with a long established trading relationship, and that the tax administrations’ limited resources should be targeted accordingly. 6. CONCLUSIONS 6.1. General conclusion Currently, there is a failure to properly implement the (transitional) intra-EU VAT system which, taking into account the purpose of the internal market that is intended to facilitate intra-EU trade, often cannot be fully complied with, even by legitimate businesses. 11 Question n° 8 of the first questionnaire: “Do you think that administrative cooperation arrangements can be useful to check information provided by suppliers? Do you use administrative cooperation arrangements at the request of suppliers?” 11/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 Moreover, all the above-mentioned suggestions do not change anything in regard to the vulnerability of the present intra-EU trade VAT system to fraud. Therefore, it is considered that the work of the Group on the Future of VAT and the VAT Expert group should now concentrate on more promising scenarios, which necessarily imply legislative changes to the existing rules for intra-EU trade in goods. 6.2. Issues for further discussion in the EU VAT Forum (or a sub-group) The discussions of the sub-group identified a number of areas, in relation to the intra-EU trade in goods, that would be suitable for discussion either within the main EU VAT Forum, or as part of a sub-group (e.g. in relation to the fight against fraud), as follows: 6.2.1. Optimizing existing documentation and controls in place in business, changing the approach. The diversity of approaches across EU Member States generates costs and increases risks for business operating in different Member States. Ideally, further harmonisation /consistency should be achieved. The diversity in the approach to intra-EU trade can be a particular challenging for SMEs, who generally have less access to information outside their own Member State and, therefore, may not be aware of all their legal obligations. Further work in making information publically available needs to be considered (e.g. discussions relating to the VAT Portal). The exchanges in the group showed that lots of the documents and information requested by tax authorities are already part of business controls. However, the answers to the questionnaire show one important difference between businesses and tax administrations in relation to the status and the commercial weight placed on the receipt of payment from a customer. Business stresses that this fact is a key element in their business process giving a tangible indication that the intra-EU transaction took place in accordance with the contract agreed between the supplier and acquirer. Member States pointed out that in the current state of the legislation, payment as such is not adequate to document the physical movement of the goods properly as required by Article 138 of Directive 2006/112. The requirement to provide proof in relation to an intra-EU supply of goods made under Ex-Works delivery terms, or where there is no third-party transport carrier involved, can be particularly problematic. The use of agreed documents in such cases to ‘certify’ that goods have left the Member State of dispatch can assist in providing a supplier with some certainty as to the VAT treatment, so long as these are optional and alternative evidence is still acceptable. The use of such documents could be considered in conjunction with an appropriate application of the ‘knowledge test’. 6.2.2. Increase the efficiency of tax administrations: Promote a risk based strategy in tax administrations? From the discussion, it emerged that a minority of Member States have introduced their own end-to-end risk analysis system. 12/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 The advantage of such tools was stressed on numerous occasions by business. Some of the advantages of a robust IT risk based analysis, put forward include: - monitoring of registration conditions, reliable VIES numbers, efficient deregistration measures; - enabling some transactions to be cleared in advance, or in real-time, which brings legal certainty for both parties; - enabling tax authorities to concentrate their resources on targeted audit when needed; - improving the conditions for fair competition and the competitiveness of legitimate business; - it is a cost effective investment: the costs of the system, resources and IT is compensated for by an increase in tax yield/collected (in the experience of one Member State in four months); - enabling authorities to know more about the taxpayer and to assess the risks across a broad range of fiscal obligations and relationships. For example, the existence of a long lasting confidence based relationship between businesses partners (or transactions within corporate groups) could be taken into consideration by tax authorities. 6.2.3. Exercise of Controls by Businesses and Tax Authorities: Preventing and Tackling Fraud Although the focus of the sub-group was the proof requirements for intra-EU supplies of goods, assuming trade between legitimate businesses, it was recognised that the promotion of an effective single market requires that both businesses and Member States work together to tackle and prevent fraud. Although there has been an increasing focus on proof and additional information requirements to tackle fraud, such an approach can only detect fraud after the event. Accordingly, any expert group on the fight against fraud should consider what measures could be taken to prevent fraud, which may include the following: what controls do businesses currently undertake as part of their internal risk management process that demonstrate that they have taken every reasonable step to verify the good standing of their customer and what would be considered best practice?; how would, or should, those controls be different in the case of a new customer, or where there is a long standing commercial relationship between the parties?; are there practices, or internal controls, applied by businesses that would be of assistance in tackling fraud if adopted by Tax Authorities?; what best practices could tax authorities adopt to check the status of a taxable person before it assigns that person a VAT identification number, or in the case of a change of ownership?; 13/14 taxud.c.1(2014)57825 – VAT Expert Group VEG No 027 how can communications between businesses and tax authorities be improved to aid the effective fight against fraud, taking into account that the fact of it’s often changing nature? 6.3. CLOSING CONSIDERATIONS FROM A BUSINESS PERSPECTIVE - Business representatives believe that the level of demands from tax authorities to document intra-EU trade should not be upgraded systematically because of recent fraud cases. One reason for not escalating this is that very few fraud cases are discovered on the basis of missing documents and that additional information can only detect fraud after the event, rather than prevent it, as the fraudster is able to provide impeccable documents. Intelligence about the companies seems to be more effective in identifying clients at risks. - There is also a need for further guidance to improve clarity and legal certainty in the interpretation and practice of certain tax authorities following recent CJEU case law. The concept of good faith is fairly subjective; the other conditions (for instance “all due commercial care”) are also very general and leave a wide margin of interpretation to national tax authorities as well as to national judges. - Business representatives believe that proof of an intra-EU supply of goods should, where possible, be based on documents that are produced in the context of a legitimate commercial arrangement. Documents that are not part of the normal commercial environment are easier for the fraudster to replicate and place additional cost burdens on legitimate businesses. - Some participants raised questions about recent changes in national legislation leading to new documents, or certificates, being used in certain circumstances. Provided that those measures are in line with EU law, the trend towards more complex and demanding procedures in the Member States as proof of intra-EU supplies is not a good signal as compliance costs are involved. It could be a deterrent for SME’s in particular to develop their activities within the EU. - Business representatives believe that a supplier should have certainty as to whether he can VAT exempt a supply at the time at which an invoice is raised. Although the option of charging VAT and then crediting such VAT when additional proof of an intra-EU supply has been provided by a customer is often suggested, the commercial reality is that this puts the supplier in the worst of both worlds in that the customer will invariably refuse to pay that VAT and the supplier is left with the risk of being liable for VAT if the proof is not provided (notwithstanding having taken reasonable steps to verify the good standing of his customer). 14/14