The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus and Mean Value Theorem 2

advertisement

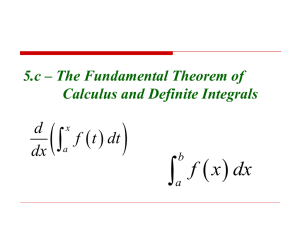

1 The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus and Mean Value Theorem 2 We’ve learned two different branches of calculus so far: differentiation and integration. Finding slopes of tangent lines and finding areas under curves seem unrelated, but in fact, they are very closely related. It was Isaac Newton’s teacher at Cambridge University, a man name Isaac Barrow (1630 – 1677), who discovered that these two processes are actually inverse operations of each other in much the same way division and multiplication are. It was Newton and Leibniz who exploited this idea and developed the calculus into its current form. The Theorem Barrow discovered that states this inverse relation between differentiation and integration is called The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus. FToC1 bridges the antiderivative concept with the area problem. This result, while taught early in elementary calculus courses, is actually a very deep result connecting the purely algebraic indefinite integral and the purely analytic (or geometric) definite integral. To evaluate an integral, take the antiderivatives and subtract. It can be proved and the proof can be found elsewhere (WEB) It is a “shortcut” rule for integration: an easier way (from Riemann sums and other methods) to calculate definite integrals. 2 𝒃 𝑭𝑻𝒐𝑪 𝟏 ∫ 𝒇(𝒙) 𝒅𝒙 = 𝑭(𝒃) − 𝑭(𝒂) 𝒂 3 4 𝒙 𝑭𝑻𝒐𝑪 𝟐 (𝒑𝒂𝒓𝒕 𝟏) 𝑭(𝒙) = ∫ 𝒇(𝒕) 𝒅𝒕 𝒖𝒑𝒑𝒆𝒓 𝒃𝒐𝒖𝒏𝒅𝒂𝒓𝒚 𝒊𝒔 𝒙 𝒂 where 𝑓 is a continuous function on [𝑎, 𝑏], and 𝑥 varies between 𝑎 and 𝑏. Notice that this integral equation is a function of 𝑥, which appears as the upper limit of integration. If 𝑓(𝑡) happens to be positive, and we let 𝑥 𝜖 (𝑎, 𝑏] , then we can define 𝐹(𝑥) as the area under the curve from 𝑎 to 𝑥. 5 𝑥 𝑥 𝐹(𝑥) = ∫(𝑡 2 + 𝑡 + 1) = ( 3 𝑡3 𝑡2 𝑥3 𝑥2 33 + + 𝑡)| = + +𝑥− 3 2 3 2 2 3 𝑑 𝑥3 𝑥2 33 ( + + 𝑥 − ) = 𝑥2 + 𝑥 + 1 𝑑𝑥 3 2 2 𝒙 𝑭𝑻𝒐𝑪 𝟐 (𝒑𝒂𝒓𝒕 𝟐) 𝒅 𝑭′ (𝒙) = ∫ 𝒇(𝒕)𝒅𝒕 = 𝒇(𝒙) 𝒅𝒙 𝒂 𝑥 𝐹(𝑥) = ∫ cos 𝑡 𝑑𝑡 𝐹 ′ (𝑥) =? −𝜋 Directly: 𝐹 ′ (𝑥) = cos 𝑥 Or, longer way: 𝑥 𝑑 𝑑 𝐹 ′ (𝑥) = ∫ cos 𝑡 𝑑𝑡 = (sin 𝑡] 𝑑𝑥 𝑑𝑥 −𝜋 = d x 1 1 dt 2 dx 0 1+t 1 x2 𝑥 ) Lower limit of integration is a constant. −𝜋 𝑑 (sin 𝑥 − sin(−𝜋)) = 𝑐𝑜𝑠 𝑥 𝑑𝑥 6 What if upper limit is g(x) not x itself? Or upper limit is constant and lower limit is x? 𝑭𝑻𝒐𝑪 𝟐 , 𝒎𝒐𝒔𝒕 𝒈𝒆𝒏𝒆𝒓𝒂𝒍 𝒇𝒐𝒓𝒎 𝒈(𝒙) 𝒅 [ ∫ 𝒇(𝒕)𝒅𝒕 = 𝒇[𝒈(𝒙)] ∙ 𝒈′ (𝒙) − 𝒇[𝒉(𝒙)] ∙ 𝒉′(𝒙)] 𝒅𝒙 𝒉(𝒙) Example 10: Evaluate the following using the FTOC2, then if feeling bored verify by doing in the Loooooooong way. 7 Geometric interpretation: For a positive function 𝑓(𝑥), there exists at least one number 𝑎 ≤ 𝑐 ≤ 𝑏 such that the rectangle with base [𝑎, 𝑏] and height 𝑓(𝑐) has the same area as the region under the graph of 𝑓(𝑥) from 𝑎 to 𝑏. Solution: 12 𝜋𝑡 ∫0 [50 + 14𝑠𝑖𝑛 (12)] 𝑑𝑡 1 12 𝜋𝑡 12 14 𝐴𝑣𝑔 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 = = ≈ 58.913 [50𝑡 − 14 𝑐𝑜𝑠 ( )]| = 50 + 2 12 − 0 12 𝜋 12 0 𝜋 8 Solution: 2 2 ∫−1[1 + 𝑥 2 ]𝑑𝑥 1 𝑥3 1 8 1 𝑓(𝑐) = = [𝑥 + ]| = [2 + − (−1) − (− )] = 2 2 − (−1) 3 3 −1 3 3 3 1 + x2 = 2 ⟹ 𝑐 = ± 1 for x = ± 1 For positive function 𝑓(𝑥) = 1 + 𝑥 2 , there exist two numbers 𝑐 = ±1 such that the rectangle with base [−1, 1] and height 𝑓(±1) has the same area as the region under the graph of 𝑓(𝑥) from -1 to 2. Solution: The average rate of change of a car’s position over an interval is represented graphically as the slope of the secant line to the graph position/time over the interval. 𝑣𝑎𝑣𝑔 = 𝑥(𝑡2 ) − 𝑥(𝑡1 ) 𝑡2 − 𝑡1 Average value of velocity over the same interval is: 𝑡2 𝑣𝑎𝑣𝑔 1 = ∫ 𝑣(𝑡) 𝑑𝑡 𝑡2 − 𝑡1 𝑡1 9 𝑡2 𝑡2 1 1 1 [𝑥(𝑡2 ) − 𝑥(𝑡1 )] 𝑏𝑦 𝐹𝑇𝑜𝐶 1 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑜𝑓: ∫ 𝑣(𝑡) 𝑑𝑡 = ∫ 𝑥′(𝑡) 𝑑𝑡 = 𝑡2 − 𝑡1 𝑡2 − 𝑡1 𝑡2 − 𝑡1 𝑡1 𝑡1 Solution: 𝑓𝑎𝑣𝑔 = ∑ 𝑓(𝑥) ≈ 40.429 7 Area area = 1160 average=1160/30 ≈ 38.667 trapezoidal approximation is more accurate that LRAM (basically arithmetic mean) Sometimes we might have to solve an integral equation! Being able to simplify definite integrals with variables in the interval of integration is important. Here are a couple of examples showing an important application that is important. Solution: 𝑏 1 ∫(2 + 6𝑥 − 3𝑥 2 )𝑑𝑥 = 3 𝑏 0 2 + 3𝑏 − 𝑏 2 = 3 → 𝑏 2 − 3𝑏 + 1 = 0 → 𝑏= 3 ± √5 2 10 Solution: Solution: (𝑎) 2 𝑓(𝑥) = ∫(2𝑥 2 − 2)𝑑𝑥 = 𝑥 3 − 2𝑥 + 𝐶 3 𝑓(0) = 5 =𝐶 2 𝑓(𝑥) = 3 𝑥 3 − 2𝑥 + 5 𝑥 (𝑏) 𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(0) + ∫ 𝑓 0 𝑓(2) = 19 3 2 ′ (𝑥)𝑑𝑥 𝑓(2) = 5 + ∫(2𝑥 2 − 2)𝑑𝑥 = 0 19 3 In the previous example, the first method relied heavily upon our ability to find the antiderivative of the integrand. This is not always easy, possible, or prudent! Being able to express a particular value of a particular solution to a derivative as a definite integral is of paramount importance, especially when we don’t know how to find a general antiderivative. (calculator can do easily definite integrals – see problem 20) 11 Hard Facts To Refute: A. Where you are at any given time is a function of 1) where you started and 2) where you’ve gone from your starting point (displacement). B. What you have at any given moment is a function of 1) what you started with plus 2) what you’ve accumulated since then. When you accumulate at a variable rate, you can to use the definite integral to find your net accumulation. Important Idea of Accumulation********************************(* means VERY IMPORTANT) What one has now = What one started with + What one has accumulated since one started This can be expressed mathematically as Example 19: If 𝑓 ′ (𝑥) = 4𝑠𝑖𝑛2 (2𝑥) and 𝑓(2) = −2 find (a) and integral equation for f(x) (b) f(3) Solution: 𝑥 (c) f(-2) 𝑥 𝑎) 𝑓(𝑥) = 𝑓(2) + ∫ 4𝑠𝑖𝑛2 (2𝑥)𝑑𝑥 = 𝑓(2) + 2 ∫(1 − cos 4𝑥)𝑑𝑥 = 2 2 𝑥 1 = 𝑓(2) + 2𝑥|2𝑥 − sin 4𝑥| 2 2 cos 2𝑥 = 𝑐𝑜𝑠 2 𝑥 − 𝑠𝑖𝑛2 𝑥 1 = −2 + 2𝑥 − 4 − sin 4𝑥 + sin(8) 2 1 𝑓(𝑥) = 2𝑥 − 6 − sin 4𝑥 + sin(8) 2 3 𝑏) 𝑓(3) = 𝑓(2) + ∫ 4𝑠𝑖𝑛 2 cos 2𝑥 = 1 − 2𝑠𝑖𝑛2 𝑥 → 𝑠𝑖𝑛2 𝑥 = 1 − cos 2𝑥 2 cos 2𝑥 = 1 − 2𝑠𝑖𝑛2 𝑥 → 𝑐𝑜𝑠 2 𝑥 = 1 + cos 2𝑥 2 3 2 (2𝑥)𝑑𝑥 = 𝑓(2) + 2 ∫(1 − cos 4𝑥)𝑑𝑥 = 2 3 1 1 1 = −2 + 2𝑥|32 − sin 4𝑥| = −2 + 6 − 4 − sin 12 + sin(8) 2 2 2 2 1 1 𝑓(3) = sin 8 − sin 12 2 2 −2 −2 b) 𝑓(−2) = −2 + ∫2 4𝑠𝑖𝑛2 (2𝑥)𝑑𝑥 = −2 + 2 ∫2 (1 − cos 4𝑥)𝑑𝑥 = −2 1 1 1 = −2 + 2𝑥|−2 = −2 − 4 − 4 − sin(−8) + sin(8) 2 − sin 4𝑥| 2 2 2 2 𝑓(−2) = sin(8) − 10 12 Solution: Solution: 𝑥 𝑥 𝑔(𝑥) = 𝑔(2) + ∫ 𝑔′(𝑥) 𝑑𝑥 = −𝜋 + ∫ 𝑒 𝑠𝑖𝑛 𝑥 𝑑𝑥 (𝑎) 𝑔(2) = −𝜋 2 2 𝜋 0 (𝑏) 𝑔(𝜋) = −𝜋 + ∫ 𝑒 𝑠𝑖𝑛 𝑥 𝑑𝑥 ≈ −1.169 (𝑐) 𝑔(𝜋) = −𝜋 + ∫ 𝑒 𝑠𝑖𝑛 𝑥 𝑑𝑥 ≈ −7.378 2 2 Solution: 𝑡 𝑊(𝑡) = 𝑊(0) + ∫ 𝑊′(𝑡) 𝑑𝑡 ⟹ 𝑊(14) = 180 + 𝑊(𝑡)|14 0 0 𝑊(14) = 180 + 10 𝑠𝑖𝑛 7𝜋 ≈ 172.930 4 𝑑𝑢𝑟𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝐶ℎ𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑡𝑚𝑎𝑠 𝑡𝑖𝑚𝑒? 𝑤ℎ𝑜 𝑐𝑜𝑜𝑘𝑒𝑑?