Migration and Inheritance: Evidence from the - eea

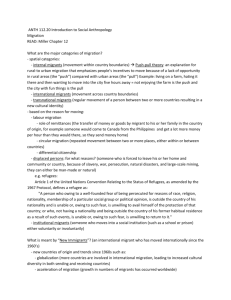

advertisement