File

Essay #1

POLS 1100 – Sp2010

Emma Panti

Defining Moments in History

With each significant event in history, we can see the juxtaposition of the branches of government. The infamous Japanese American internment, for example helps to define the specific powers of both the President and the Supreme Court.

Background

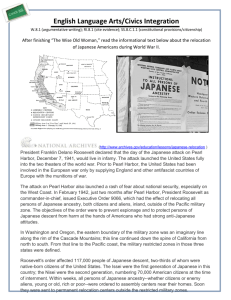

On December 7 th , 1941, the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese took Americans completely by surprise. It was this action that brought the United States into World War II.

Additionally, this launched America into a national security state, meaning that every aspect of life was dominated by national defense. Up to this point Japan had deceived the United States by maintaining a false interest in continued peace. This newly revealed deception gave cause for hysteria and immense prejudice against the Japanese.

In addition to public frenzy, anti-Japanese attitudes were common amid farmers and small business owners who had been forced to compete against cheap Japanese labor. In light of recent events, it wasn’t difficult to compel politicians to side with anti-Japanese constituencies.

Executive Order

Shortly following the attack, General DeWitt drafted a report stating that because of their national origin, it was impossible to establish the allegiance of any Japanese Americans. In spite of lacking evidence that Japanese Americans were involved in the attacks on Pearl Harbor, DeWitt’s

recommendation to increase security was primarily focused on the internment of all those of Japanese descent, living in certain areas.

Initially, the Justice Department felt the evacuation was unnecessary, even unconstitutional as a majority of these Japanese Americans were US citizens. Nonetheless DeWitt and others pushed for execution of the order.

DeWitt’s recommendations were heartily accepted among the heads of the War Departments.

Chief of Staff George C. Marshall read and approved the report. In order to circumvent lengthy legislative processes, the report was then presented to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. On February 19,

1942, Roosevelt suspended habeas corpus by signing Executive Order 9066, permitting the exclusion of civilians from wartime military zones. The signing of this order also gave way for the military to enact mass evacuation and internment of Japanese Americans from these zones. Despite the order allowing the exclusion of “any persons”[1], the order was only enforced against those of Japanese origin.

The Camps

The authorized military zones were primarily in the Western States. Although zones were established in various states, the mass evacuation was not equally imposed among them. Japanese in

California and Arizona, for example were detained at much higher rates as compared to those in Hawaii.

Families were forced to leave behind their businesses, animals and most of their belongings to relocate to over-crowded, poorly built and somewhat dirty living quarters. Many Japanese were given such little notice that efforts to sell possessions proved futile. This was a huge financial loss and burden for many of these detainees. In addition to the forced evacuation, zone curfews were instituted as well.

Landmark Litigation

Two court cases drew considerable attention to the Japanese American Internment. These landmark cases are known as Hiribayashi vs. United States and Korematsu vs. United States. Both litigants filed suit against the United States contending that their fifth amendment rights had been violated.

Hiribayashi was convicted of violating a curfew and relocation order and appealed his conviction. The US Supreme Court upheld the conviction, not on the grounds of race, but on the grounds that the curfew had indeed been violated. This case had set precedent for other cases that followed.

Korematsu’s suit took on the United States in a much broader scope. He argued that the

Executive Order signed by Roosevelt had been unconstitutional. The circuit court of appeals, through a writ of certiorari, petitioned a judicial review of his case by the US Supreme Court. Unlike the majority of opinion by the Supreme Court Justices in the Hiribayashi case, Korematsu’s proceedings were met with dissenting opinions.

Probably the most vocal of the three dissenting votes was Justice Frank Murphy. Murphy stated the Executive Order for the internment “falls into the ugly abyss of racism”[3] and considered it

“abhorrent and despicable treatment of minority groups by the dictatorial tyrannies which this nation is now pledged to destroy…” [3] He called the entire incident “legalization of racism” [3]. In spite of

Murphy’s efforts the US Supreme Court ruled that the internment was constitutional in a 6-3 majority vote.

Presidential Powers

Just as President Roosevelt usurped his Presidential Power in executing the evacuation order, he rescinded the order two and a half years later, and the camps were closed.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford issued a Proclamation confirming the cease of that order. It was in that order Ford states, “I call upon the American people to affirm with me this American Promise

-- that we have learned from the tragedy of that long-ago experience forever to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American, and resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated.

“[4]

In 1988, President Reagan signed into legislation an official apology for the internment. The apology stated that the government actions were based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” [2]

Both the proclamation and new legislation were pivotal in setting new precedent with regards to Fifth Amendments rights during time of war; especially considering similar racial hysteria surrounding the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Defining Moments

Clearly the ushering of the Japanese Americans into these camps demonstrates the presidential power to act unilaterally in the name of national security. In contrast, this event also illustrates the authority of the Supreme Court to scrutinize the constitutionality of those Presidential Policies.

Works Cited

1.

Wikipedia contributors. "Japanese American internment." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 4 Mar. 2010. Web. 5 Mar. 2010.

2.

"It Happened in America...." Exploring the Japanese American Internment through Film & the

Internet. Web. 5 Mar 2010.

3.

Siasoco & Ross. "Japanese Relocation Centers." Infoplease 2007: n. pag. Web. 5 Mar 2010.

4.

Ford, Gerald B. United States. By the President of the United States of America, a Proclamation.

Washington, DC: Ford Library, 2000. Web. 5 Mar 2010.