Janie Vanpée - American Society for Eighteenth

advertisement

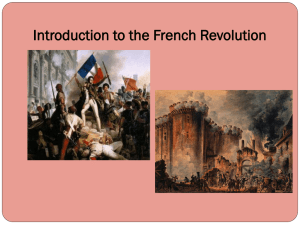

1 Re-Membering Marie Antoinette A First-year seminar Janie Vanpée Smith College « The term History, unites the objective with the subjective side, and denotes… not less what has happened, than the narration of what has happened. » G.F.W. Hegel, The Philosophy of History Introductory remarks: Looking back through the presentations from previous recipients of the Innovative Course Design competition, I couldn’t help but notice a recurrent motif. Most of the scholar teachers design their courses in reponse to a perceived need to interest students in a field— eighteenth-century literature, culture, history—that no longer attracts them automatically. It may always have been the case that we scholars and teachers of this period have had to work hard to make the period relevant to our students, but I find that it has become increasingly so, especially in the foreign language departments where ever shrinking faculty positions mean that curricular offerings have had to be condensed and rethought. In many foreign language departments in small liberal arts colleges without graduate programs, we no longer have the luxury to devote an entire course to a period that may draw only a few advanced students who have the language abilities to read, write and discuss in the language of the texts on the syllabus. But there is a positive side to this state of affairs. As the forum for Innovative Course Design that ASECS has now sponsored for more than a dozen years demonstrates repeatedly, many colleagues have developed inventive approaches to teaching the 18th-century in courses that make the issues of the period relevant to today’s students. I, too, started the project of designing this course, Re-Membering Marie Antoinette, from the premise that it must first attract the interest of students who might otherwise not consider studying anything about the French eighteenth century. I was further challenged by the problem of making the course relevant to first-year students and to an increasing percentage of foreign students. I could not count on either of these overlapping groups to have much knowledge of the period. Organizing the course around the figure and myth of Marie Antoinette seemed the obvious solution. Sofia Coppola’s 2006 film was and remains a cult film among young women. 2 The film sparked or coincided with renewed trends in fashion and pop culture, inspired by late eighteenth-century styles. From my own, more academic, perspective, a number of scholarly works on Marie Antoinette also appeared around that time, notably Dena Goodman’s selection of essays gathered in Writings on the Body of a Queen,(2003), Caroline Weber’s Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution (2006), as well as David Grubin’s PBS documentary, Marie Antoinette (2006). The collective effect of these works and films had regenerated interest in Marie Antoinette. In a recent article published in Literature/Film Quarterly, Suzanne Ferris and Mallory Young, propose that popular interest in Marie Antoinette can be attributed to the contemporary phenomenon of chick culture. They go on to argue, In studying the phenomenon of chick culture, we have become interested particularly in the intersection of postfeminism or third-wave feminism, consumerism, and popular media. And here is where Marie Antoinette’s popular resurrection is located. Marie Antoinette is capturing the Spirit of the Third-Wave Feminist Age. [“Marie Antoinette, Fashion, Third-Wave Feminism and Chick Culture,” Literature/Film Quarterly 38: 2 (2010): 98] According to this view, an effective advertising campaign to capture the interest of the Smith College first-year female students was already in place. Goals and Parameters: I designed the course as a first-year seminar and I taught it for the first time in the fall of 2011. First-year seminars at Smith share several goals: they are writing intensive; they introduce students to the rich array of resources available on a university or college campus setting; and they conduct an intellectual query that entails an interdisciplinary exploration. In addition to these shared pedagogical and methodological goals, Re-Membering Marie Antoinette aimed to introduce students to a complex historical period, to certain aspects of material culture of eighteenth-century France, and to a varied selection of literary genres that flourished at the time. I wanted the course to function as an introduction to the eighteenth century and to count toward the French Studies major, should students be drawn subsequently to pursue the study of French. [Indeed, 3 out of the 16 students declared their intention to major in French at the conclusion of the course and a few more were inspired to continue studying French.] 3 The course proposes to achieve these goals by focusing on one historical personage, Marie Antoinette, from a variety of perspectives—historical and contemporary; a variety of genres—literary and visual; and a variety of methods—historical, literary, and theatrical. The intellectual query driving all our investigations is whether or not one can comprehend, seize or capture, imagine or come close to understanding an historical personage. Can we possibly understand who Marie Antoinette was and her role at that particular juncture of European history? And if so, how is the representation we imagine in our minds of Marie Antoinette accomplished? How close does it coincide with or how far does it diverge from the person she was? Indeed can we separate our imagination of the personnage and period from the knowledge we may acquire? While the answer to these questions may seem intuitively obvious, the course focuses on the process of arriving at the conclusion that we can only capture an historical personage as a fractured mosaic of bits of information, opinion, images, documents and accounts, guiding the students through a variety of approaches that both enhance and contradict aspects of their increasingly complex understanding of who Marie Antoinette was, thus leading them to a more nuanced appreciation of the possibilities and limitations of historical inquiry. Pedagogical approaches: The primary goal of the writing intensive seminar is, of course, to improve written expression at the academic level. To achieve this goal, students produce a variety of different types writing, from the informal paragraph written in class, to a narrative from a specific point of view, a detailed description of a portrait, a comparative essay, a short research paper, and a convincing argument in a more formal academic style. Each of the four units of the course develops from a sequence of scaffolded assignments that allows students to work up form lowstakes exercises to a longer, more polished essay at the end of each unit. Through individual writing conferences and collective editing workshops students are encouraged to develop a critical stance toward their own writing, revising their essays and helping peers develop stronger writing skills. Because effective writing intersects with articulate speaking, students also work on oral presentation skills, both informal and formal, individual and collaborative. The final project of re-enacting Marie Antoinette’s trial fuses both written and oral works as students engage in discussion, debate and articulating specific arguments that they have developed in writing and then revised to take into account oral arguments. 4 To encourage cognitive reflection as part of the process of understanding conflicting or changing perspectives, many of the assignments are posted on a class blog. Sharing and commenting on each other’s views make it evident how even the students’ re-imagining of Marie Antoinette diverge. As the semester progresses, and students return to their previous postings to edit, amend or modify them, they come to a better understanding of the fluidity of their own historical re-presentations of Marie Antoinette. The blog has the additional advantage of allowing use of other digital materials beside print. Students post the culminating assignment of three for the course’s four units. For unit I, they upload their descriptive response to one of a dozen portraits of Marie Antoinette. For unit two on material culture, they develop a wall legend analyzing an object and its use as depicted in one of the prints of Moreau le Jeune’s Monument du Costume that they then contribute to the collective exhibit, Luxury Objects in the Age of Marie Antoinette. And for the fourth and last unit reenacting Marie Antoinette’s trial, they write position papers, rebuttals and responses that they post in the three broadsheets representing different political views of the Revolution. A course in four units: The following syllabus and description of assignments present a detailed roadmap of our query. Let me here summarize the four main stages of the process. The first stage or unit examines different contemporary representations of Marie Antoinette, from official and informal portraits to her own self-representation in her letters, as well as her mother’s and Count Mercy’s, the Austrian emissary at Versailles, depiction of her in their correspondence; it juxtaposes these with representations of Marie Antoinette that four different biographers imagine through their respective narratives. Students first describe their impressions of one of a dozen different portraits of Marie Antoinette at different moments of her life. They refine their description two weeks later after having worked collectively on a timeline of her life and period and having read parts of the four biographies, each of which presents a different and nuanced narrative of the same historical facts and events. Their re-writing forces them to confront their own changing understanding of Marie Antoinette, and the comparison of their descriptions in relation to the portraits in the online portrait gallery allows them also to reflect on Marie Antoinette’s evolving and fluid identity through her life. As the semester progresses, and their 5 knowledge of Marie Antoinette deepens, they will periodically return to this first “impressions” description to refine it or change it completely. The second stage of the inquiry explores the material culture, the space, the places, and the things that surrounded Marie Antoinette and shaped her body, her time, her activities, and her relations to others. Students move outside the classroom to discover the print collection in the Cunningham Gallery, the painting galleries in the Smith Museum of Art, the Rare Books room and the collection of costumes in the Theatre Department. They study in detail the prints of the Monument du Costume (Moreau le Jeune), examining the tension between private and public space inscribed within them and how the characters depicted in the prints negotiate the spaces in which they enact a series of common, but complex daily rituals—getting up, getting dressed, socializing, playing social games, strolling in parks—all of which Marie Antoinette engaged in as well. To delve more deeply behind the lovely surface appearance of prints and the objects, clothing, spaces and places depicted therein, the class visits the Rare Book Room to study the articles and plates of the Encyclopédie that describe the objects and the crafts behind the activities displayed and being used in Moreau le Jeune’s prints. Using the translations of the relevant articles posted on the Collaborative Translation Project of the Encyclopédie, students create an online exhibit on the class blog comparing one of the Monument du Costume prints with one or two objects displayed and used in the scene, and whose representation and description they found in the plates of the Encyclopédie. Students engage in individual research using library as well as online resources to give the wall label they write for the exhibit a scholarly framework. This project is collaborative, as the online exhibit showcases sixteen objects, articles of clothing, and furniture in their settings, and explores the design, labor and economy behind the objects to show how Marie Antoinette’s daily activities depended on a network of accomplished craftsmen and a complex economy of creative design and laborintensive production. The appended poster lays out the series of scaffolded assignments that build up to the final collaborative exhibit. The third stage in the inquiry turns to the struggle to control Marie Antoinette’s image and myth, from the controversy over the portraits she selected to show who she was to the portraits that adhered more closely to the official image a Queen of France had to present, to the state and stately portraits that attempted to correct the increasingly critical public view of Marie 6 Antoinette as profligate, immoral, and flouting her duties and role as Queen. The pamphlets and caricatures we study play an important role in fashioning an alternative myth of the Queen that escapes her control. The unit culminates with a comparison of two films that present different twentieth-century versions of the myth of Marie Antoinette, Sofia Coppola’s 2006 film and MGM’s 1938 star vehicle for Norma Shearer. The fourth and final step in our inquiry allows students to take on the role of different players in Marie Antoinette’s life and period and to re-enact a new version of her trial. Modeled on the Reacting to the Past game, Rousseau, Burke and Revolution in France, 1791, originally developed at Barnard College, the three-week role-play has been reconceived to feature a fictionalized reenactment of Marie Antoinette’s trial. Students receive the identity of an historical or fictive personnage at the time of Marie Antoinette’s trial with information and directives about their role. Some of the figures included in last fall’s game were Olympe de Gouges, Mme de Staël, Mme Campan, Marie Antoinette’s lady-in-waiting, Count Mercy, Count Fersen, Saint-Juste, the jailor Simon, a national guardsman, as well as a fishwife and an artisan. Students call on what they have learned of the politics, events, and culture of the period to create cohesive characters that will present a different view of Marie Antoinette. They have the opportunity to articulate orally their views, to debate with each other in the “salons” and “clubs” and to publish their character’s opinion in the broadsheets representing divergent political views. They debate more formally and as politically affiliated factions during the courtroom trial. In the final essay, they summarize the arguments for and against Marie Antoinette’s “guilt” calling upon all they have learned during the course of the semester to make their case. I’ve appended a brief outline of the major “acts” of the role-play. At this fourth and final stage of the inquiry, students have encountered an array of different perspectives on Marie Antoinette presented in a variety of genres and formats, from archival sources of documents and letters, to biographies, portraits—official and unofficial— caricatures, pornographic pamphlets, fictional works such as plays, novels and films in which she figures. As they consolidate their image and judgment of Marie Antoinette, they will have learned through the process of sifting through these sometimes contradictory representations that the image they construct will be just that—a construction, based partly on facts, partly on 7 compelling narratives, partly on memorable images, partly on their imagination framed by their own contemporary period, and lastly on their own unique recombination of these parts. The course was conceived to evolve into a next stage—a senior seminar taught in French, to be taught two years from now. Although many sources have been translated into English, more documents and sources are available in French. The basic premise of the course will remain the same—an interdisciplinary exploration of the re-presentation of an historical figure, using both traditional references and digital resources. However, students in the senior seminar will be expected to delve more deeply into the struggles and stages of the French Revolution and produce a more extensive research paper. I also hope to have students post some of the preliminary research they do on the Revolution on the interactive digital map of Paris that my colleague Hélène Visentin is developing. Students will have access to a map of Paris during the Revolution and upon which they will be able to link their findings to the spaces and sites on the map, thus adding a spatial understanding to their historical research. As a senior seminar in French, the course will be able to exploit more source materials in the original or those only available in French such as Germaine de Staël’s Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine [1793] or films such as Eric Rohmer’s Le Duc et l’Anglaise. The last unit reenacting Marie Antoinette’s trial will engage them in a global simulation exercise that should give them the opportunity to polish their polemical abilities in French. Appended: 1. Syllabus with dates for Fall 2012 2. Bibliography 3. Synopsis of writing assignments 4. Description of the five acts of the reenactment of Marie Antoinette’s trial 5. Poster representing the scaffolded assignments for unit 2 on material culture