Prevalence of trichomoniasis in pregnancy

advertisement

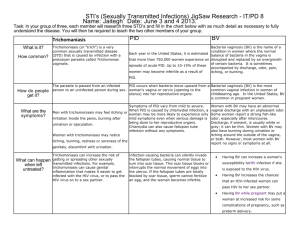

CONSULTATION DRAFT 7.4 Trichomoniasis Identifying the cause of vaginitis symptoms enables a woman to make an informed decision about treatment during pregnancy. 7.4.1 Background Trichomoniasis is a common sexually transmitted vaginitis caused by the single-celled protozoan parasite Trichomonas vaginalis. Around 70% of people with trichomoniasis do not experience symptoms (Workowski & Berman 2010). When symptoms are present in women, they include a smelly, yellow-green vaginal discharge with vulvar irritation (Workowski & Berman 2010). Trichomoniasis is associated with infertility, pelvic inflammatory disease and enhanced HIV transmission (Sobel 2005; Sutton et al 2007; Johnston & Mabey 2008; Fichorova 2009). Prevalence of trichomoniasis in pregnancy Trichomoniasis is the most common curable sexually transmitted infection globally, with a prevalence among women of 8.1% (WHO 2011). Prevalence varies with age as well as geographical region. • Population-level data: There are no accurate national data available regarding the prevalence of trichomoniasis in Australia and the infection is not notifiable. • Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women: Small studies of discrete populations have found an prevalence among pregnant women of 15.5–17.6% (Josif et al 2012) in remote areas and 7.2% in an urban area (Panaretto et al 2006). • Country of origin: Prevalence in the United States is in the range of 3–3.7% (French et al 2006; Sutton et al 2007; Mann et al 2009), higher among African American women (10–14%) (Caliendo et al 2005; Miller et al 2005; French et al 2006) and slightly lower among adolescent women (2.8%)(Miller et al 2005). Prevalence in other regions has been estimated as 0.3–6% among South American women (Lobo et al 2003; Gondo et al 2010), 5.5–8.5% among Asian women (Sami & Baloch 2005; Azargoon & Darvishzadeh 2006; Madhivanan et al 2009) and 5.4–17.6% among African women (Adu-Sarkodie 2004; Stringer et al 2010). • Risk factors: Risk factors include multiple sexual partners, previous sexually transmitted infections, non-use of barrier contraceptives, work in the sex industry, intravenous drug use, smoking, low socioeconomic status and incarceration (Brown 2004; Say & Jacyntho 2005; Johnston & Mabey 2008; Workowski & Berman 2010). Risks associated with trichomoniasis in pregnancy • Pregnancy risks: Trichomoniasis in pregnancy is associated with increased risk of preterm birth and low birth weight (Buchmayer et al 2003; Mann et al 2009; Gülmezoglu & Azhar 2011). • Risks to the baby: Maternal trichomoniasis has been associated with genital and respiratory infections of the newborn (Carter & Whithaus 2008; Trintis et al 2010). 7.4.2 Screening for trichomoniasis Summary of the evidence In the United States (Workowski & Berman 2010), testing for trichomoniasis during pregnancy is only recommended for women with symptoms. Recommendations on screening have not previously been developed in the United Kingdom or Australia. Specimen collection Small low-level studies in non-pregnant populations have concluded that: • self-collected vaginal swabs correlate with specimens collected by health professionals (Smith et al 2005; Kashyap et al 2008; Huppert et al 2010) and are easy to perform (Kashyap et al 2008); and CONSULTATION DRAFT • self-collection by tampon sampling is acceptable to women (van de Wijgert et al 2006), is easily incorporated into practice and may be suitable in remote settings as samples do not require refrigeration (Garland & Tabrizi 2004). Diagnostic test accuracy A range of testing methods for trichomoniasis is used in Australia; the most appropriate test will depend on the clinical setting. • Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of vaginal swabs has high sensitivity (96–100%) and specificity (97–100%) (Lobo et al 2003; Caliendo et al 2005; Smith et al 2005; Pillay et al 2007). Small studies have found that PCR testing of tampon samples has high sensitivity (94–100%) (Knox et al 2002; Sturm et al 2004). PCR testing of urine samples has lower sensitivity and specificity (76.7% and 97%) (Pillay et al 2007). • Culture testing of vaginal swabs has high sensitivity (63.0–98.2%) and specificity (99.4–100%) (Lobo et al 2003; Adu-Sarkodie 2004; Caliendo et al 2005; Smith et al 2005). It requires an incubator and culture medium, and may take up to 7 days for a result. • Wet mount microscopy has low sensitivity (43.6–81.5%) but a high specificity (93–100%) (Lara-Torre & Pinkerton 2003; Lobo et al 2003; Adu-Sarkodie 2004; Smith et al 2005; Pillay et al 2007). Accurate diagnosis depends on immediate evaluation of a moist specimen and the skill of the examiner (Hollier & Workowski 2005). • Pap smear is not adequate as the sole method of diagnosis of trichomoniasis because of its low sensitivity (60.7–72.1%) and the delay in obtaining results (Lara-Torre & Pinkerton 2003; Lobo et al 2003; Smith et al 2005). There is insufficient evidence to assess the accuracy of the latex agglutination kit in diagnosing trichomoniasis (Adu-Sarkodie 2004). Benefits and harms of screening While accurate diagnostic tests are available, the benefits of screening are limited by uncertainties about the effect of treatments during pregnancy. Advantages of identifying and treating trichomoniasis include relief of symptoms, reduced risk of further transmission and possible prevention of genital and respiratory infections in the newborn (Workowski & Berman 2010). Potential harms of screening include false positive diagnosis (Johnson et al 2007) and adverse effects associated with treatment (see below). In areas of high prevalence, all women should be screened for trichomoniasis as part of regular women’s health screening. It is preferable that woman be tested either before or after the pregnancy, to avoid adverse effects of treatment. Recommendation 14 Grade B Offer testing to women who have symptoms of trichomoniasis, but not to asymptomatic women, during pregnancy. Availability of safe and effective treatments for trichomoniasis Metronidazole and tinidazole are used to treat trichomoniasis (Owen & Clenney 2004; Fung & Doan 2005; Wendel & Workowski 2007; Workowski & Berman 2010). The Therapeutic Goods Administration classifies metronidazole as pregnancy category B2 and tinidazole as B3. Based on the limited evidence available, treatment with metronidazole provides parasitological cure in around 90% of women and would likely be more effective if partners were also treated (Workowski & Berman 2010; Gülmezoglu & Azhar 2011). However, it does not reduce risk of preterm birth or low birth weight in asymptomatic women (Gülmezoglu & Azhar 2011) and may increase the risk of preterm birth (Carey & Klebanoff 2003; Hay & Czeizel 2007). Studies into the effect of treatment in women with symptomatic trichomoniasis are also limited and findings are inconsistent. Some suggest an increased incidence of preterm birth (Riggs & Klebanoff 2004; CONSULTATION DRAFT Okun et al 2005) and others found no association with preterm birth (Mann et al 2009). Findings may be affected by method of assessing gestational age (Stringer et al 2010) and timing of diagnosis. Due to the lack of clarity on the risk of preterm birth, treatment of asymptomatic pregnant women is not recommended but may be a consideration after 37 weeks gestation. Treatment for women with symptoms requires consideration of the risks and benefits for the individual woman. Repeat screening Due to the high rates of reinfection among women diagnosed with trichomoniasis, rescreening 3 months following treatment may be a consideration, although this approach has not been evaluated (Workowski & Berman 2010). 7.4.3 Discussing trichomoniasis Discussion to inform a woman’s decision-making about trichomoniasis screening should take place before testing takes place and include: • it is the woman’s choice whether she has the test or not; • trichomonisasis is a common sexually transmitted infection and most people do not experience symptoms; • trichomoniasis is associated with increased risk of preterm birth and low birth weight and may cause some types of infection in the newborn; • treatment of trichomoniasis relieves symptoms, reduces the risk of transmission and may prevent related infections in the newborn but may not reduce the risk of preterm birth; • testing and treatment of partners is advisable if infection is identified and the couple should abstain from sex until treatment is complete and symptoms have resolved; and • testing for other sexually transmitted infections may be needed. 7.4.4 Practice summary: trichomoniasis When: A woman has signs or symptoms of vaginitis. Who: Midwife; GP; obstetrician; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioner; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker; multicultural health worker, sexual health worker. Discuss the reasons for testing for trichomoniasis: Explain that testing is necessary to identify the cause of the symptoms. Take a holistic approach: If a woman is found to have trichomoniasis, other considerations include counselling, contact tracing, partner testing and treatment and testing for other sexually transmitted infections. Document and follow-up: If a woman is tested for trichomoniasis, tell her the results and note them in her antenatal record. Have a system in place so that women’s decisions about treatment are documented and women who test positive for trichomoniasis during pregnancy are given ongoing follow-up and information. 7.4.5 Resources Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in pregnancy. In: Minymaku Kutju Tjukurpa Women’s Business Manual, 4th edition. Congress Alukura, Nganampa Health Council Inc and Centre for Remote Health. http://www.remotephcmanuals.com.au Workowski KA & Berman S (2010) Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 59(RR-12): 1–110. 7.4.6 References Adu-Sarkodie Y (2004) Comparison of latex agglutination, wet preparation, and culture for the detection of Trichomonas vaginalis. Sex Transm Infect 80(3): 201–03. CONSULTATION DRAFT Azargoon A & Darvishzadeh S (2006) Association of bacterial vaginosis, trichomonas vaginalis, and vaginal acidity with outcome of pregnancy. Arch Iran Med 9(3): 213–17. Brown D, Jr. (2004) Clinical variability of bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis. J Reprod Med 49(10): 781–86. Buchmayer S, Sparen P, Cnattingius S (2003) Signs of infection in Pap smears and risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 17(4): 340–46. Caliendo AM, Jordan JA, Green AM et al (2005) Real-time PCR improves detection of Trichomonas vaginalis infection compared with culture using self-collected vaginal swabs. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 13(3): 145– 50. Carey JC & Klebanoff MA (2003) What have we learned about vaginal infections and preterm birth? Semin Perinatol 27(3): 212–16. Carter JE & Whithaus KC (2008) Neonatal respiratory tract involvement by Trichomonas vaginalis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Trop Med Hyg 78(1): 17–19. Fichorova RN (2009) Impact of T. vaginalis infection on innate immune responses and reproductive outcome. J Reprod Immunol 83(1-2): 185–89. French JI, McGregor JA, Parker R (2006) Readily treatable reproductive tract infections and preterm birth among black women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 194(6): 1717–26; discussion 26–27. Fung HB & Doan TL (2005) Tinidazole: a nitroimidazole antiprotozoal agent. Clin Ther 27(12): 1859–84. Garland SM & Tabrizi SN (2004) Diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections (STI) using self-collected non-invasive specimens. Sexual Health 1(2): 121–26. Gondo DC, Duarte MT, da Silva MG et al (2010) Abnormal vaginal flora in low-risk pregnant women cared for by a public health service: prevalence and association with symptoms and findings from gynecological exams. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 18(5): 919–27. Gülmezoglu AM & Azhar M (2011) Interventions for trichomoniasis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(5): CD000220. Hay P & Czeizel AE (2007) Asymptomatic trichomonas and candida colonization and pregnancy outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 21(3): 403–09. Hollier LM & Workowski K (2005) Treatment of sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy. Clin Perinatol 32(3): 629– 56. Huppert JS, Hesse E, Kim G et al (2010) Adolescent women can perform a point-of-care test for trichomoniasis as accurately as clinicians. Sex Transm Infect 86(7): 514–19. Johnson HL, Erbelding EJ, Ghanem KG (2007) Sexually transmitted infections during pregnancy. Curr Infect Dis Rep 9(2): 125–33. Johnston VJ & Mabey DC (2008) Global epidemiology and control of Trichomonas vaginalis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 21(1): 56–64. Josif C, Kildea S, Gao Y et al (2012) Evaluation of the Midwifery Group Practice Darwin. Midwifery Research Unit, Mater Medical Research Institute and Australian Catholic University. Kashyap B, Singh R, Bhalla P et al (2008) Reliability of self-collected versus provider-collected vaginal swabs for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Int J STD AIDS 19(8): 510–13. Knox J, Tabrizi SN, Miller P et al (2002) Evaluation of self-collected samples in contrast to practitioner-collected samples for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis by polymerase chain reaction among women living in remote areas. Sex Transm Dis 29(11): 647–54. Lara-Torre E & Pinkerton JS (2003) Accuracy of detection of trichomonas vaginalis organisms on a liquid-based papanicolaou smear. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188(2): 354–56. Lobo TT, Feijo G, Carvalho SE et al (2003) A comparative evaluation of the Papanicolaou test for the diagnosis of trichomoniasis. Sex Transm Dis 30(9): 694–99. Madhivanan P, Krupp K, Hardin J et al (2009) Simple and inexpensive point-of-care tests improve diagnosis of vaginal infections in resource constrained settings. Trop Med Int Health 14(6): 703–08. Mann JR, McDermott S, Zhou L et al (2009) Treatment of trichomoniasis in pregnancy and preterm birth: an observational study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 18(4): 493–97. Miller WC, Swygard H, Hobbs MM et al (2005) The Prevalence of Trichomoniasis in Young Adults in the United States. Sex Transm Dis 32(10): 593–98. Okun N, Gronau KA, Hannah ME (2005) Antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis or Trichomonas vaginalis in pregnancy: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 105(4): 857–68. Owen MK & Clenney TL (2004) Management of vaginitis. Am Fam Physician 70(11): 2125–32. Panaretto KS, Lee HM, Mitchell MR et al (2006) Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections in pregnant urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in northern Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 46(3): 217–24. Pillay A, Radebe F, Fehler G et al (2007) Comparison of a TaqMan-based real-time polymerase chain reaction with conventional tests for the detection of Trichomonas vaginalis. Sex Transm Infect 83(2): 126–29. Riggs MA & Klebanoff MA (2004) Treatment of vaginal infections to prevent preterm birth: a meta-analysis. Clin Obstet Gynecol 47(4): 796–807; discussion 81–82. Sami S & Baloch SN (2005) Vaginitis and sexually transmitted infections in a hospital based study. J Pak Med Assoc 55(6): 242–44. Say PJ & Jacyntho C (2005) Difficult-to-manage vaginitis. Clin Obstet Gynecol 48(4): 753–68. CONSULTATION DRAFT Smith KS, Tabrizi SN, Fethers KA et al (2005) Comparison of conventional testing to polymerase chain reaction in detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in indigenous women living in remote areas. Int J STD AIDS 16(12): 811– 15. Sobel JD (2005) What's new in bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis? Infect Dis Clin North Am 19(2): 387–406. Stringer E, Read JS, Hoffman I et al (2010) Treatment of trichomoniasis in pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa does not appear to be associated with low birth weight or preterm birth. S Afr Med J 100(1): 58–64. Sturm PD, Connolly C, Khan N et al (2004) Vaginal tampons as specimen collection device for the molecular diagnosis of non-ulcerative sexually transmitted infections in antenatal clinic attendees. Int J STD AIDS 15(2): 94–98. Sutton M, Sternberg M, Koumans EH et al (2007) The prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among reproductive-age women in the United States, 2001-2004. Clin Infect Dis 45(10): 1319–26. Trintis J, Epie N, Boss R et al (2010) Neonatal Trichomonas vaginalis infection: a case report and review of literature. Int J STD AIDS 21(8): 606–07. van de Wijgert J, Altini L, Jones H et al (2006) Two methods of self-sampling compared to clinician sampling to detect reproductive tract infections in Gugulethu, South Africa. Sex Transm Dis 33(8): 516–23. Wendel KA & Workowski KA (2007) Trichomoniasis: challenges to appropriate management. Clin Infect Dis 44 Suppl 3: S123–29. WHO (2011) Prevalence and incidence of selected sexually transmitted infections – Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhaoe, syphilis and Trichomonas vaginalis. Geneva: World health Organization. Workowski KA & Berman S (2010) Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 59(RR-12): 1–110.