Tavakoli - Saddleback College

advertisement

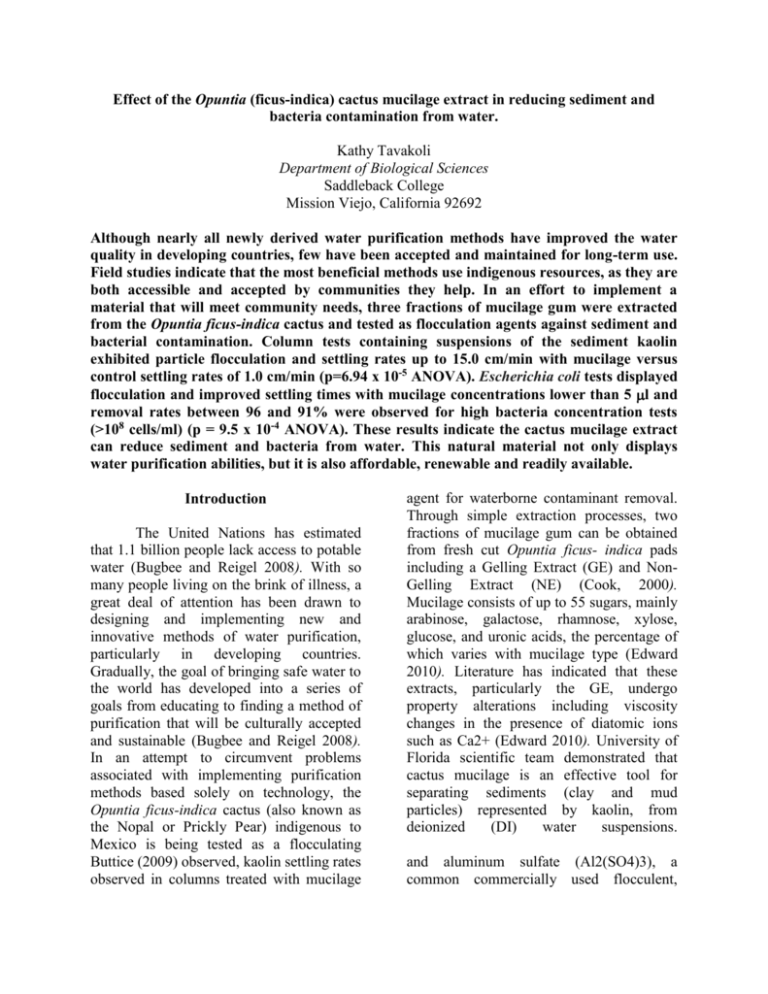

Effect of the Opuntia (ficus-indica) cactus mucilage extract in reducing sediment and bacteria contamination from water. Kathy Tavakoli Department of Biological Sciences Saddleback College Mission Viejo, California 92692 Although nearly all newly derived water purification methods have improved the water quality in developing countries, few have been accepted and maintained for long-term use. Field studies indicate that the most beneficial methods use indigenous resources, as they are both accessible and accepted by communities they help. In an effort to implement a material that will meet community needs, three fractions of mucilage gum were extracted from the Opuntia ficus-indica cactus and tested as flocculation agents against sediment and bacterial contamination. Column tests containing suspensions of the sediment kaolin exhibited particle flocculation and settling rates up to 15.0 cm/min with mucilage versus control settling rates of 1.0 cm/min (p=6.94 x 10-5 ANOVA). Escherichia coli tests displayed flocculation and improved settling times with mucilage concentrations lower than 5 l and removal rates between 96 and 91% were observed for high bacteria concentration tests (>108 cells/ml) (p = 9.5 x 10-4 ANOVA). These results indicate the cactus mucilage extract can reduce sediment and bacteria from water. This natural material not only displays water purification abilities, but it is also affordable, renewable and readily available. Introduction The United Nations has estimated that 1.1 billion people lack access to potable water (Bugbee and Reigel 2008). With so many people living on the brink of illness, a great deal of attention has been drawn to designing and implementing new and innovative methods of water purification, particularly in developing countries. Gradually, the goal of bringing safe water to the world has developed into a series of goals from educating to finding a method of purification that will be culturally accepted and sustainable (Bugbee and Reigel 2008). In an attempt to circumvent problems associated with implementing purification methods based solely on technology, the Opuntia ficus-indica cactus (also known as the Nopal or Prickly Pear) indigenous to Mexico is being tested as a flocculating Buttice (2009) observed, kaolin settling rates observed in columns treated with mucilage agent for waterborne contaminant removal. Through simple extraction processes, two fractions of mucilage gum can be obtained from fresh cut Opuntia ficus- indica pads including a Gelling Extract (GE) and NonGelling Extract (NE) (Cook, 2000). Mucilage consists of up to 55 sugars, mainly arabinose, galactose, rhamnose, xylose, glucose, and uronic acids, the percentage of which varies with mucilage type (Edward 2010). Literature has indicated that these extracts, particularly the GE, undergo property alterations including viscosity changes in the presence of diatomic ions such as Ca2+ (Edward 2010). University of Florida scientific team demonstrated that cactus mucilage is an effective tool for separating sediments (clay and mud particles) represented by kaolin, from deionized (DI) water suspensions. and aluminum sulfate (Al2(SO4)3), a common commercially used flocculent, were compared and mucilage was concluded to induce a greater increase in settling rate (Young 2011). Related tests also indicate that mucilage extracted from the Opuntia spp. acts as an efficient coagulant in surrogate turbid water (Young 2011). In this work, the efficiency of mucilage to remove kaolin suspended in DI-Water was evaluated. Aside from sediment intrusion, another common problem associated with drinking water has been bacterial contamination. Even in more developed countries where purification and distribution systems are technologically advanced and water is closely monitored, cases of waterborne illnesses caused by bacteria are occasionally observed (Cook, 2000). In developing countries, issues with bacterial contamination are more severe. Escherichia coli, a Gram-positive, spore- forming, nonpathogenic, soil-dwelling rod (∼1 by 3 μm), was chosen to study bacterial aggregation with mucilage for its ease of use and potential as a possible surrogate for waterborne bacteria with similar structural characteristics. Data on its effects could impact the status of this widely used product and may have influence in water purification industries. Material and Method Pads were obtained from Opuntia ficus-indica cactus, originally purchased from Crown Valley Market, located in Crown valley Parkway, Mission Viejo. This method and procedure is replicate of the project conducted by University of Southern Florida, Buttice (2009) study. The 3 cactus pads (average weight 252 g) were diced, heated with Nuova stir-hot-plate for 20 minutes at 85 oC, (water bath) and then the solution was naturalized to pH 7-7.5 with 4 mL of 1 M NaOH. The pads were liquidized by Braun blender with high speed (range 4) for 5 minutes. The pH adjusted to 7 using approximately 4 mL of 1 M NaOH solution and the solid separated using Clay Adams Compact II Centrifuge and 12 - test tube placed (6 test tubes at a time) in there with 3200-RPM speed for 10 minutes. The precipitate was removed and used in the extraction of GE and the supernatant was reserved for the acquisition of NE. In precipitate, a 50 mM NaOH with 0.75% (w/w) was added until the precipitate was covered and then stirred with Nuova stirhot-plate for 30 min. The pH was adjusted to 2 using 12 mL of 0.1 M HCl solution, the mixture centrifuged, and the supernatant discarded. The precipitate was re-suspended in DI water, and the pH was increased to 8 using 5 mL of 1 M NaOH. This suspension was filtered via vacuum filtration using #41 Whatman filter. The portion of the original suspension that was reserved for extraction of NE was mixed with 200 mL of 1 M NaCl solution and filtered using #41 Whatman filter and a vacuum filtration system. The filtrates of both the NE and GE were separately mixed with acetone (1:1 v/v), spread upon watch-glass dishes and left overnight for allowing water to evaporate. The recovered mucilage was removed and washed in isopropanol (1:1 v/v), and some NE (v/v) were mixed with GE mucilage to make CG (combined- gelling). The mucilage that spread upon watch-glass dishes, dried, ground using mortar and pestle and some of them stored for further experiments. Unused mucilage suspension was stored in the refrigerator for future use. The two distinct fractions of mucilage gum were studied for their different characteristics and removal abilities. Simple test tubes were used to evaluate the flocculation effect of the mucilage. The test tube contents (mucilage and DI- water) were Result Kaolin Removal with Cactus Mucilage. Kaolin suspension in DI water was treated with 0, 2 l, 5 l and 10 l concentrations for each GE (gelling mucilage), NE (non gelling mucilage) and CG (combined gelling mucilage), which is demonstrated two characteristic of the mucilage induced settling (n=10). Frist it was observed that as mucilage concentration increased, for all NE, GE, and CG, so did the removing rate of the kaolin (Figure 2). Initially (without any mucilage), the relationship between concentration and settling rate appeared to be linear (Figure 1). concentrations. The final and initial concentration read by Marienfeld Hemocytometer plate and Nikon microscope (For accurate result, count ten (10) of the 1/16 sq. mm squares. Calculate the average value and multiply by 1.6 X 105 to determine the number of cells per milliliter). E.coli did not from a visible interface while settling. The time when flocs began to appear as small white flecks in the otherwise turbid water time that the flocs ceased to fall was recorded. Box plot were used to represent settling times, where the bottom of the box indicates the time when flocs were no longer falling in the column. The dotted lines represent the start (lower line) and completion time (upper line) of the control columns containing only E.coli. Once the flocs had completed their descent, a 1 mL sample was taken from the top of the column and final cell counts were evaluated using hemocytometer plate and microscope microscope. The resulting bacteria concentration was compared to the initial and final concentration and a removal rate was obtained base on clarity. Kaolin Settling Rate (cm/min) mixed to 10 mL in 15 mL centrifuge tubes, vortexed and poured in to column arrays, which were observed over a period of time. Kaolin (hydrated aluminum silicate) was ordered online from “Allied Products Wholesale” via “eBay”. The suspension with final concentration 25g/500 L were set up in the Di-water at least 24 h prior to the run of the experiment to allow kaolin particles thorough hydration time. In test tubes tests of specific concentrations, kaolin has been observed to from a clear interface which was read every minute fro up 60 min, and the column marker at the interface was recorded for ate plotting. These plots were truncated where compression in the column began and settling rate in cm/min was obtained. The Escherichia coli were cultured overnight, with final column cell count 108 cell/mL. The final concentration was determined with direct counting chamber and Hemocytometer plate. 8 dilution tubes were taken, each containing 9.0 mL of sterile saline. Aseptically diluted 1.0 mL of a sample of E. coli. Dilution was repeated for total 10 final tubes each containing 108 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 0 5 10 Concentration (ppm) Figure 1. The effect of the control solution (nonmucilage) on the settling rate of kaolin (50 g/L) suspended in DI water. 15 highest removable solution, and after CG for 86% (15 cm initial to 2.1 cm final), and NE (15 cm initial to 3.5 cm final) with 79%, each remove kaolin from water (Figure 3). Kaolin Settling Rate (cm/min) 9.4 9.2 9.0 8.8 8.6 8.4 16.0 8.2 NE (2 uL) NE (5 uL) NE (10 uL) Kaolin Settling Rate (cm/min) 8.0 7.5 7.0 6.5 14.0 12.0 Average CG(cm/min) 10.0 Average GE (cm/min) Contorl cm Average NE (cm/min) 8.0 6.0 4.0 2.0 0.0 6.0 GE (2uL) Kaolin Settling Rate (cm/min) Kaolin Settling Rate (cm/min) 8.0 GE (5uL) GE (10 uL) 9.0 8.8 8.6 8.4 8.2 8.0 CG (2 uL) CG (5 uL) CG (10 uL) Figure 2. The effect of the mucilage concentration, for all NE, GE, and CG, on the settling rate of kaolin (50 g/L) suspended in DI water. As the concentration increase, settling rate of kaolin decrease (reducing rate increase). Second, it was observed that with no mucilage treatment, all kaolin suspension settled at rate close to 15 cm/min, indicating that any differences observed among the treated suspensions were primarily due to ion interaction with the mucilage. Base on the result, it can be indicate the mucilage extract did reduce the kaolin from water. There was significant statistically difference between GE, NE, and CE mucilage in removing kaolin (p = 6.94 x 10-5 ANOVA). GE mucilage observed 92% removable kaolin sediment from water in 60 min (15 cm initial to 1.2 cm final), which became a 0 20 40 60 Time ( min ) Figure 3. Comparing the average Kaolin settling rate (cm/min) with removing sediments time in each 1 minute, for 60 minutes, with respect to the GE, NE, CG and control (non-gelling) solutions (n=10). GE mucilage observed most removable kaolin sediment from water in 60 minutes (15 cm initial to 1.2 cm final). There was significant statistically difference between GE, NE, and CE mucilage in removing kaolin (p = 6.94 x 10-5 ANOVA). Escherichia coli Removal with Cactus Mucilage. Arrange of mucilage concentration were tested to evaluate the effect of mucilage on the settling time. The settling rate of E. coli with 5 l NE, GE, and CG were obtained from columns contacting steamed water and 108 (cell/min) diluted E. coli (n =10). From comparing the initial counting E. coli cells and final counting, indicated that mucilage extract did remove E. coli from water. The difference in initial and final concentration shows that there is statistically difference between NE, GE, and CG solutions in reducing E. coli from water (p = 9.5 x 10-4 ANOVA). Difference concentration in GE was more 0.29 (cell/min), which indicated the most removable E. coli from water. At GE concentration of 5 l, signs of flocculation (14:95 min:sec) occurred faster than NE (17:34 min:sec) and CG (23:35 min:sec) mucilage. Bacteria removable rate associated with 5 l GE, NE, and CG were determined to be 96.43% , 94.35%. and 91.24% (Figure 4). Difference in bacteria concentartion 0.35 0.30 0.25 0.20 0.15 0.10 0.05 0.00 NE (5 uL) GE (5 uL) CG (5 uL) Figure 4. The effects of the mucilage extracts (NE, GE, CG) to the difference concentration of E. coli (cell/min) (initial - Final) (n=10). Difference concentration in GE was more 0.29 (cell/min), which indicated the most removable E. coli from water. The difference in initial and final concentration shows that there is statistically difference between NE, GE, and CG solutions in reducing E. coli from water (p = 9.5 x 10-4 ANOVA). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. Discussion An important difference between the mucilage ‘s ability to aggregate kaolin particle compared to bacteria was that there existed a concentration where the bacteria was that reacted to the mucilage in positive manner. In columns contacting kaolin, increases in mucilage concentration resulted in higher settling rate, but no concentrations were observed to restrict settling as seen in suspension of E. coli. Also, in columns containing kaolin, the GE appeared to cause larger increase in settling rate while the NE seems to work slightly better as a treatment for E. coli suspension cause the flocs that formed appeared as organized, stable, and larger as those formed in GE, and CG. The indicated results are equivalent to the University of Florida studies (2009) studies, observed that small amount of mucilage that is required for contaminant removal from surrogate waters. Although in this research, as diatomic ions are known to affect both mucilage and promote cell aggregation, CaCl2 was studied in conjunction and compared with mucilage as a bacteria removal method in three different kind of water (Hard/Soft/DI), which each contain different ions and Bacillus cereus was tested to displayed flocculation and improved settling times. The experiment that performed in Saddleback College was base on the specific sediment (kaolin) and bacteria (Escherichia coli), with different concentration in mucilage for kaolin and same concentration but repeated three times for bacteria (more accurate result). In addition in Young (2011) demonstrated the use of Non-Gelling (NE) and Gelling (GE) Extract; mucilage fractions for removal of sediment in DI water. He concluded that both mucilage fractions act faster in sediment removal than the controls containing no flocculating agent, and solutions treated with the commonly used Alum. He suggested the combined gelling solution for future experimentations. In Saddleback College experiment, the NE, GE were testing in addition of CG as new experiment and the results are new, since it could find in another research experiment for result comparison. The result that observed here indicated there is significant difference in effect of the mucilage extract (NE, GE, and CG ) in reducing bacteria and kaolin from water. The result observed the GE solution had removed more kaolin and bacteria in less time from water; compare to NE removed less kaolin and take much long to flocs. In CG result, it appear to have removing settling rate and flocculation time in between GE and NG, from this results, It appears the CG solution have characteristics from both gelling and non-gelling, which is part that we observed in non-experimental cactus pad. Although these removal rates are high, the level of bacteria remaining in the columns renders the water still unsafe to drink. This is due to the initial cell concentration (108 cell/mL), which would not be typically observed in the real world, but was used to obtain a visual indicator of flocculation and removal. Future experimentation will involve optimizing parameters for bacteria removal at lower level of contamination. The results discussed in this work demonstrate the potential of mucilage extracted from the Opuntia ficusindica as flocculation agent for sediment and bacteria contamination in ion rich water. The cactus’ prevalence, affordability, and cultural acceptance make it an attractive natural material fro water purification technologies that could be beneficial in Mexico and around world. The difference mucilage fractions have been observed to provide diversity both in their structural features as well as in their reactions to the natural ion concentration in water they are treating. Literature Cited Opuntia Polyacantha (Plains Prickly-Pear) in Great Plains Grasslands. Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences. pp 996. - Bugbee, R.E. and A. Reigel. 2008. The cactus moth, Melitara dentata (Grote), and its effect on Opuntia macrorhiza in western Kansas. pp 1-94. - Buttice, Audrey Lynn. 2009. Reducing sediment and bacterial contamination in water using mucilage extracted from the Opuntia ficus- indica cactus. Graduate School Theses and Dissertations.pp 1-9. - Larsen, N.; Nissen, P.; Willatts. 2007. The effect of calcium ions on adhesion and competitive exclusion of Lactobacillus.ssp and E. coli O138. Int. J. Food Microbiol. , 114, 113–119. - Lauenroth, William K.; Dougherty, R. L. and Singh, J. S. 2009. Precipitation Event Size Controls on Long-Term Abundance of Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the generous support received from Professor Teh who supplied the necessary equipment and guidance to make the research happen. In addition, we thank Saddleback College Biological Sciences Department for allowing us to use their facilities in the study. - Edward, Lin. 2010. Removal of Sediment and Bacteria from Water Using Green Chemistry, Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 (9). pp 3514-3519. - Grant, V. and K.A. Grant. 2010. Systematics of the Opuntia phaeacantha group in Texas. Bot. Gaz. Opuntia lindheimeri group. Bot. Gaz. pp 1-18. - Natural Standard Monograph. 2013. Nopal(Opuntia) The Authority on Integrative Medicine,accessed 12 FEB 2011. - Young, N. 2011. The medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature Magazine . 480. pp 520–524.