the gettysburg address as literature

advertisement

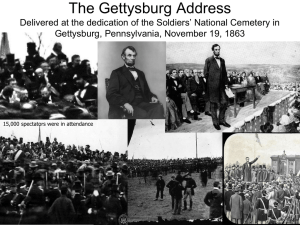

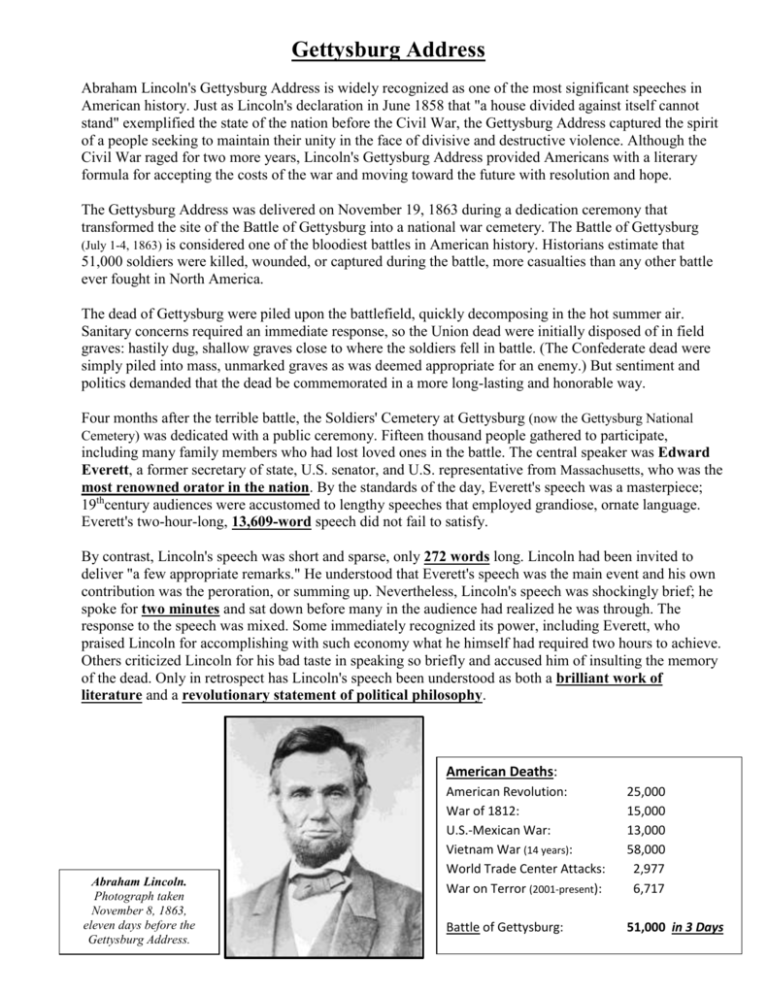

Gettysburg Address Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address is widely recognized as one of the most significant speeches in American history. Just as Lincoln's declaration in June 1858 that "a house divided against itself cannot stand" exemplified the state of the nation before the Civil War, the Gettysburg Address captured the spirit of a people seeking to maintain their unity in the face of divisive and destructive violence. Although the Civil War raged for two more years, Lincoln's Gettysburg Address provided Americans with a literary formula for accepting the costs of the war and moving toward the future with resolution and hope. The Gettysburg Address was delivered on November 19, 1863 during a dedication ceremony that transformed the site of the Battle of Gettysburg into a national war cemetery. The Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-4, 1863) is considered one of the bloodiest battles in American history. Historians estimate that 51,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured during the battle, more casualties than any other battle ever fought in North America. The dead of Gettysburg were piled upon the battlefield, quickly decomposing in the hot summer air. Sanitary concerns required an immediate response, so the Union dead were initially disposed of in field graves: hastily dug, shallow graves close to where the soldiers fell in battle. (The Confederate dead were simply piled into mass, unmarked graves as was deemed appropriate for an enemy.) But sentiment and politics demanded that the dead be commemorated in a more long-lasting and honorable way. Four months after the terrible battle, the Soldiers' Cemetery at Gettysburg (now the Gettysburg National Cemetery) was dedicated with a public ceremony. Fifteen thousand people gathered to participate, including many family members who had lost loved ones in the battle. The central speaker was Edward Everett, a former secretary of state, U.S. senator, and U.S. representative from Massachusetts, who was the most renowned orator in the nation. By the standards of the day, Everett's speech was a masterpiece; 19thcentury audiences were accustomed to lengthy speeches that employed grandiose, ornate language. Everett's two-hour-long, 13,609-word speech did not fail to satisfy. By contrast, Lincoln's speech was short and sparse, only 272 words long. Lincoln had been invited to deliver "a few appropriate remarks." He understood that Everett's speech was the main event and his own contribution was the peroration, or summing up. Nevertheless, Lincoln's speech was shockingly brief; he spoke for two minutes and sat down before many in the audience had realized he was through. The response to the speech was mixed. Some immediately recognized its power, including Everett, who praised Lincoln for accomplishing with such economy what he himself had required two hours to achieve. Others criticized Lincoln for his bad taste in speaking so briefly and accused him of insulting the memory of the dead. Only in retrospect has Lincoln's speech been understood as both a brilliant work of literature and a revolutionary statement of political philosophy. American Deaths: Abraham Lincoln. Photograph taken November 8, 1863, eleven days before the Gettysburg Address. American Revolution: War of 1812: U.S.-Mexican War: Vietnam War (14 years): World Trade Center Attacks: War on Terror (2001-present): 25,000 15,000 13,000 58,000 2,977 6,717 Battle of Gettysburg: 51,000 in 3 Days THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS Although it is now celebrated as a masterpiece, the Gettysburg Address was not fully appreciated by its original audience. But in 272 words, Lincoln succeeded in transforming the horrific violence of the Battle of Gettysburg into a vision for a unified American nation, built squarely upon the premise that "all men are created equal." Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom— and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth. The Gettysburg Address in Modern Language 87 years ago, the Founding Fathers created a brand new country here based on the idea that everyone is equal. Now, we are at war with ourselves, and this war is testing whether that kind of country can survive. A great battle of this war was fought right here where we are standing. We are here today to dedicate a part of this battlefield as a cemetery for the soldiers that died here—they gave their lives and died so that this nation could live. So, dedicating this place for them is the right thing to do. But, there is no way that we can dedicate, or ever bless this ground more than the soldiers that died here already have. We can’t even come close. History is not going to pay much attention to or remember long what we say here, but no one can ever forget what those soldiers did here. It’s up to the rest of us that are still alive to dedicate ourselves to finishing what these soldiers have started. It’s up to us to dedicate ourselves to saving the country, and remind ourselves that people have died for this cause. We have to promise that the soldiers here did not die for nothing. We have to promise that this country, under God, will have a new and even greater freedom for all. We have to promise that a country that is made up of the people, was created by the people, and made to serve the people can exist in this world. THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS AS LITERATURE The Gettysburg Address exemplifies the transformative power of language; in 272 words, Lincoln replaced the violence and carnage of the Battle of Gettysburg with a vision of a unified nation committed to equality. Lincoln's brevity and simplistic language is deceptive, giving the impression that the text was extemporaneous. Indeed, since the Gettysburg Address was first delivered, a myth has developed that Lincoln wrote the speech quickly on the train from Washington, D.C., to Pennsylvania. Contrary to this myth, there are five copies of the speech in Lincoln's handwriting; this shows that Lincoln revised the text several times before and after he delivered it in 1863. It is the fifth draft of the speech, known as the "Bliss copy" after its owner Colonel Alexander Bliss, which has become accepted as the standard edition of the text. Rather than a spontaneous response to the battle-field cemetery, the Gettysburg Address is a precisely crafted literary text that distills Lincoln's complex political ideals to their essence. The multiple drafts of the text are a testament to the care with which Lincoln composed the speech as well as his awareness of the subtle nuance of each word. The Gettysburg Address is often described as a prose poem because of the significance of Lincoln's word choices. In addition, certain lines of the address have a lyrical rhythm and regular structure that evoke the sensibility of poetry, such as: "we cannot dedicate, cannot consecrate, cannot hallow." The use of repetition in this phrase creates a rhythm that carries the audience from what they cannot do to what they must do: dedicate themselves to a government "of the people, by the people, for the people." These two phrases occur at the beginning and end of the final paragraph and thus create a unified structure that models through language what the speech seeks to accomplish through politics. In addition to his ingenious use of rhythm and repetition, Lincoln employs powerful literary imagery, primarily in the form of antithesis or the comparison of opposites such as light/dark or new/old. Lincoln uses antithesis in the juxtaposition of birth and death; although he acknowledges that death occasions the speech, his language evokes images of birth: "brought forth," "conceived," "new birth of freedom." Thus he replaces the grim reality of the dead with the hopeful idea of rebirth and continuity. Similarly, Lincoln links the past and the future, beginning the speech with a look backwards ("Four score and seven years ago") but concluding with a repetition of active verbs that point toward the future: the dead shall not have died in vain, the nation shall have a new birth of freedom, the government shall not perish. The complex meaning achieved by the few words Lincoln uses also draws attention to the words he did not use: North/South, Union/Confederacy, or slavery. He never mentions Gettysburg or the particulars of the battle. He never mentions the South as either enemy or challenger. It is also striking that he does not mention the other historically significant text of 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation that freed the slaves. By avoiding mention of the specific issues, participants, and events that dominated the war, Lincoln sought to transform them into types, abstract and idealistic rather than tangible and ordinary. This allows Lincoln to transcend the particulars of the war and focus upon the principles at stake. In a similar way, Lincoln employs general terms rather than proper nouns throughout: a civil war, a battlefield, any nation rather than the Civil War, the Gettysburg battlefield, the United States. This technique reflects Lincoln's knowledge of classical oratorical tradition; inspired by speeches like Pericles' funeral oration for the Athenian dead in 431 B.C.E., Lincoln sought to elevate the dead of Gettysburg into inspirational symbols. In Lincoln's formulation, the dead should be commemorated by the rededication of the living to the principles of equality and unity. Thus, America itself becomes the lasting monument to the Civil War dead. THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS AS POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY The Gettysburg Address is one of Lincoln's most revolutionary political speeches. Although he had been invited to simply give his approval to the creation of the Gettysburg National Cemetery, Lincoln took advantage of the time and place to take a stand on the controversial issues that sparked the Civil War. Even though he does not specifically mention slavery or states' rights, the address is understood as a turning point in the development of Lincoln's thinking about these complex political debates. In the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln turns away from the Constitution as the document that defines the parameters of American policy. Instead, Lincoln embraces the Declaration of Independence and the phrase "all men are created equal" as the cornerstone of the nation. By looking to the Declaration for guidance, Lincoln implicitly acknowledges the flaws of the Constitution, such as its provisions for the existence of slavery. The answer to the great "test" the nation is undergoing is a rededication to the original intent of the declaration. The consequences of Lincoln's statements are profound: he acknowledges the incompatibility of slavery and equality and implies that the Constitution must be amended to set the nation back on the correct path, thus anticipating the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery in 1865. In his Pulitzer Prize winning account of the Gettysburg Address, the historian Gary Wills argues that Lincoln's speech was more than just a great work of oratory. Instead, he writes, the Gettysburg Address resulted in a revolutionary re-conception of American identity: “The Gettysburg Address has become an authoritative expression of the American spirit— authoritative as the Declaration itself, and perhaps even more influential, since it determines how we read the Declaration. For most people now, the Declaration means what Lincoln told us it means, as a way of correcting the Constitution itself without overthrowing it. . . . By accepting the Gettysburg Address, its concept of a single people dedicated to a proposition, we have been changed. Because of it, we live in a different America.” THE GETTYSBURG ADDRESS IN AMERICAN MEMORY The Gettysburg Address is celebrated as a masterpiece of American literature. Although many scholars identify Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address (1865) as his greatest work of oratory and political philosophy, it is the Gettysburg Address that remains foremost in most people's minds when they think of Lincoln. Both the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural are inscribed upon the walls of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. The association between the man and his words has worked to elevate both in American memory. As Lincoln's reputation has ascended since his death in 1865, so too have historians, literary critics, and politicians come to recognize the remarkable accomplishment of the Gettysburg Address. Continuing a long-standing tradition, every year innumerable school children across the nation still commit Lincoln's words to memory. Even as the deaths suffered in 1863 fade from memory, the power of Lincoln's words live on. On September 11, 2002, one year after the attacks on the World Trade Center, New York governor George Pataki participated in a memorial service at Ground Zero. Rather than deliver an original speech about the terrible events of 2001, Pataki chose to simply read Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. This employment of Lincoln's words suggests that they transcend the specific losses of the Civil War and capture instead a national experience of grief in the face of almost unimaginable violence and loss.