Backgrounder - JCFs and Donor Screening

advertisement

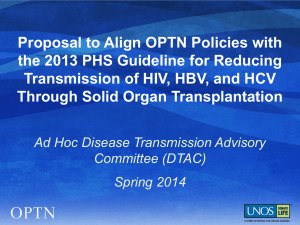

CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening We received the following information from FDA/CBER after they reviewed the Child Uniform DRAI dated as final draft 6-10-14: Re: HCT/P Donor Eligibility (Final) Guidance (section IV.E.8.) recommendation: Persons who have been in juvenile detention, lock up, jail or prison for more than 72 consecutive hours in the preceding 12 months (Refs. 29, 67, and 68) (risk factor for HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C). AATB’s related DRAI (donor ≤ 12 years old) question: Not applicable for a Child Donor Assessment. FDA comments: Federal law does not specify a minimum age for which a child could be placed in juvenile detention. Instead, the minimum age may be set by individual states. Many states do not set a minimum age, whereas others have minimum age requirements as low as 6 years old (Ref. 1). According to Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement (Ref. 2), a total of 750 children ≤ 12 years of age were detained or committed into a juvenile detention facility during 2011 in the United States. Therefore, it does appear that the recommendation described in IV.E.8. of the HCT/P Donor Eligibility Guidance would be applicable for a Child Donor Assessment. We recognize that discretion may be appropriate for children of a very young age, however individual state requirements should be kept in mind when determining whether the information request is applicable. References: 1. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Statistical Briefing Book. http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/structure_process/qa04102.asp?qaDate=2013. 2. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement. http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/asp/selection.asp. This discussion document outlines relevant issues surrounding this topic. A summary appears after performing reviews of: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) federal guidance for cells/tissues and guideline for organs (United States); guidance and standards for cells, tissues, and organs (Canada); reports available from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; reports by CDC involving juvenile correctional facilities; reports from NCHS and others that describe the development of this question for the blood donation questionnaire; 6) other relevant publications (United States); 7) a directive for screening donors of cells and tissues (European Union); and 8) an order and guidelines for biologicals, which includes cells, tissues (Australia). Scott A Brubaker Page 1 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening Summary • • Related to placement in juvenile detention (aka “juvenile correctional facility”), lock up, jail or prison, the references used in FDA guidance (2007) do not support applicability to screening children newborn to 12 years (inclusive) for increased risk associated with HIV, HBV, or HCV. There is no indication the age range newborn to 12 years should be included, however, for deceased donation, behavioral history is sourced from someone other than the donor so there should be consideration to optimize screening for risks and this could be handled by additional questioning. Guidance from Health Canada (2013) via references to normative CSA Standards (2013) recommends a donor age 12 should be screened for this risk because a child that age can be sent to prison. This is supported by Canadian Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46) and Youth Criminal Justice Act, S.C. 2002, c.1. Rates of HIV, HBV and/or HCV in this child population are not reported. • Recommendations from the PHS Guideline (2013) included analysis of publications involving the tissue donor population, and the recommendations apply to “pediatric donors.” Evaluation of risks for HIV, HBV, and HCV included “children.” The exhaustive reviews of literature (aka “best evidence available”) performed to create the PHS Guideline suggest it is not warranted to screen children newborn to 12 years (inclusive) for increased risk associated with HIV, HBV, or HCV in relation to placement in a juvenile correctional facility (aka “juvenile detention”), lock up, jail or prison. “Inmates” reported here apply only to adults and the literature review identified an applicable behavioral risk factor for HIV and HCV: “age at first sexual intercourse.” The child donor’s involvement ‘ever’ in a sexual act as well as a question regarding sexually transmitted infections are addressed by other questions on the Uniform DRAI for a donor ≤ 12 years old. • The population 12 and younger in the US can be placed in locked, detention centers/facilities, and in some states, children can be placed in jail or prison due to lack of correctional facilities for juveniles. In the majority of states, the upper age is 17 and the lower age is not specified for delinquency and status jurisdiction (2013), however, the lowest age noted for delinquency and status jurisdiction was age 6. Crimes related to behaviors that might also increase risk for HIV, HBV, and HCV (sexual assault, drug trafficking, other drug) are very low numbers (2011) that support this as a rare occurrence. But, consideration of reports that reveal there can be sexual victimization that occurs while detained in a correctional facility could play a role in screening donors in this age group. A report (2013) described that sexual victimization while detained did not occur before turning age 8. The idea being considered is to screen for this risk if the donor age is from 6 to 12 years (inclusive), or 8 to 12 years (inclusive). • National data (US) is not available for the age group of our focus. A risk category that includes juvenile detention” or “juvenile correctional facilities” for children newborn to age 12 (inclusive) has not been shown by data to exist. There is STI data (i.e., chlamydia and gonorrhea) beginning with age 12 that relates to juvenile correction facilities and a relationship to increased risk for HIV, HBV, and HCV. Risk associated with sexual acts and STIs are already covered by other questioning on the Uniform DRAI for a Donor ≤ 12 years old. It’s not clear how an additional query regarding detainment to a correctional facility can add value to screening for risk associated with HIV, HBV, and HCV. For deceased donation, behavioral history is sourced from someone other than the donor so there should be consideration to optimize screening for risks and could be handled by additional questioning. Scott A Brubaker Page 2 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening • The use of “juvenile hall” in an early version of the blood UDHQ as it was being developed and evaluated does not apply to screening children newborn to 12 years (inclusive) for increased risk associated with HIV, HBV, or HCV. The age group is too young to donate blood or blood components, and an age group younger than “high school” age was not included in the intent of the development of the question. It’s not clear how a decision was made to change “juvenile hall” to “juvenile detention” or the decision to keep the reference to “juvenile” in a final version of the blood DHQ. Guidance & Guideline – United States • Eligibility Determination for Donors of Human Cells, Tissues, and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products (HCT/Ps). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. August 2007 Pages 14 and 15 IV. DONOR SCREENING (§1271.75) E. What risk factors or conditions do I look for when screening a donor? Following is a list of conditions and behaviors that increase the donor’s relevant communicable disease risk. Except as noted in this section, and in accordance with §1271.75 (d), you should determine to be ineligible any potential donor who exhibits one or more of the following conditions or behaviors. 8. Persons who have been in juvenile detention, lock up, jail or prison for more than 72 consecutive hours in the preceding 12 months (Refs. 29, 67, and 68) (risk factor for HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C). X. REFERENCES 29. Karon, J.M., et al., Prevalence of HIV Infection in the United States, 1984 to 1992. Jama 1996; 276:126-31. 67. Food and Drug Administration Memorandum to All Blood Establishments for "Deferral of Current and Recent Inmates of Correctional Institutions as Donors of Whole Blood, Blood Components, Source Leukocytes, and Source Plasma" June 8, 1995. http://www.fda.gov/cber/bldmem/060895.txt. 68. Ruiz, J.D., et al., Prevalence and Correlates of Hepatitis C Virus Infection Among Inmates Entering The California Correctional System. West J Med 1999; 170:156-60. Review of references: Reference 29 provides an estimate of how many “children” had HIV in 1992. There is one reference that “children” included those “< 13 years of age,” and this estimate was derived from two studies. One was the Survey in Childbearing Women (SCBW) reported in 1991 but it only involved newborns infected by birth mothers. See reference 4 in the article titled: “Prevalence of HIV infection in childbearing women in the United States: surveillance using newborn blood samples.” The other information was “from AIDS case surveillance,” reference 5 in the article, with this title from 1995: “Prevalence and incidence of vertically acquired HIV infection in the United States.” It concluded that: “Approximately 6530 HIV-infected women gave birth in the United States in 1993, and, based on a 25% vertical transmission rate, an estimated 1630 of their infants were HIV infected.” Reference 29 also includes “Table 1. Estimates of HIV Prevalence, by Data Source and Sex—United States, 1992*” that describes: “Estimates include persons already diagnosed as having the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. These estimates include 10,000 children.” In the “Results” section there is one reference to children: “The estimate based on each method includes 10,000 infected children, half boys and half girls.” Reference 29 does Scott A Brubaker Page 3 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening not include any language related to “juvenile detention,” “juvenile correctional facilities,” “jail,” “prison,” or “lockup.” Conclusion: Reference 29 does not apply to screening children newborn to 12 years (inclusive) for increased risk associated with HIV, HBV, or HCV in relation to placement in juvenile detention (aka “juvenile correctional facility”), lock up, jail or prison. This reference supports screening the birth mother for risk associated with HIV and this is accomplished by completing the “Assessment of the Birth Mother,” the second half of the Uniform DRAI for a donor ≤ 12 years old, when applicable. Reference 67 provides “Recommendations for the Deferral of Current and Recent Inmates of Correctional Institutions as Donors of Whole Blood, Blood Components, Source Leukocytes, and Source Plasma” to all registered blood establishments. It describes: “that a significant proportion of inmates of correctional institutions are at increased risk of infectious diseases because of their use of illicit intravenous drugs prior to incarceration.” And that “data correlate with a high rate of infection with blood borne agents, including HIV and hepatitis viruses, and other transmissible agents in inmates entering or incarcerated in correctional facilities.” It further describes “other risk factors for HIV and hepatitis transmission, such as tattooing, and high risk sexual activity have been reported for inmates of prisons or jails. Although reports vary on the rate of seroconversion for HIV in the prison setting, transmission of HIV and HBV have been reported in the prison environment.” It concludes “This information suggests that a history of incarceration in a correctional institution is associated with behaviors, such as intravenous drug abuse, that indicate an increased risk for transfusion-transmitted infections. In addition, for current inmates the nature of the prison environment may lead to a denial of behavioral risk factors by those seeking to donate blood products, because of secondary gains. The FDA therefore recommends that: 1. Current inmates of correctional institutions (including jails and prisons) and individuals who have been incarcerated for more than 72 consecutive hours during the previous 12 months be deferred as donors of Whole Blood, blood components, Source Leukocytes, and Source Plasma for 12 months from the last date of incarceration.” A scan of the list of 47 references included in the memorandum reveals references to “prisons,” “prisoners,” “intraprison,” “jails,” “jail inmates,” “federal inmates,” “state prison inmates,” “adult arrestees,” “penitentiary,” “a municipal house of correction,” and three refer to “correctional facilities” but these references report only on adults. Additionally, per the website of the American Red Cross accessed on 26 July 2014, (http://www.redcrossblood.org/donating-blood/eligibility-requirements), “Blood Donors Must: Be at least 17-years-old in most states, or 16-years-old with parental consent if allowed by state law.” And, per the website of America’s Blood Centers accessed on 26 July 2014, http://www.americasblood.org/donate-blood/blood-donation-faqs.aspx, “Are there age limits for blood donors? Seventeen years old is the minimum blood donor age. (In some states, 16-year-olds may donate.) Some blood centers may have an upper age limit. Please call and check with your local blood center for more information.” Conclusion: Reference 67 does not apply to screening children newborn to 12 years (inclusive) for increased risk associated with HIV, HBV, or HCV in relation to placement in juvenile Scott A Brubaker Page 4 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening detention (aka “juvenile correctional facility”), lock up, jail or prison. The age group is too young to donate whole blood, blood components, source leukocytes, and source plasma. The age group from newborn to ≤ 12 years is not addressed by the article or any of its references. Reference 68 provides the following information: “The purpose of our study was twofold: (1) to estimate the prevalence of infection with hepatitis C virus among inmates entering the California correctional system and (2) to identify predictors of the risk for HCV infection among this population.” It concludes that: “Of 4,513 inmates in this study, 87.0% were men and 13.0% were women. Among male inmates, 39.4% were anti HCV positive; by race/ethnicity, prevalences were highest among whites (49.1%). Among female inmates, 53.5% were anti-HCV-positive; the prevalence was highest among Latinas (69.7%). In addition, rates for HIV were 2.5% for men and 3.1% for women; and for HBsAg, 2.2% (men) and 1.2% (women). These data indicate that HCV infection is common among both men and women entering prison. The high seroprevalence of anti-HCV-positive inmates may reflect an increased prevalence of high-risk behaviors and should be of concern to the communities to which these inmates will be released.” There is only mention of “men” and “women,” or “adult males” and “adult females.” There are no references to “child,” “children,” “adolescent,” or to “juvenile.” Two tables report data for age groups as “25 or older” and “24 or younger” but there is no indication this latter age group includes ages of children 12 years and younger. A scan of the list of 27 references included in the article produce only one that includes a report involving infants and children but it is used to support that “HCV may also be transmitted by...transplantation of organs12.” See reference 12’s title “The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in infants and children after liver transplantation.” Conclusion: Reference 68 does not apply to screening children newborn to 12 years (inclusive) for increased risk associated with HIV, HBV, or HCV in relation to placement in juvenile detention (aka “juvenile correctional facility”), lock up, jail or prison. The article and references within it are only applicable to adults and is limited to one state’s experience. Although these references aren’t a perfect fit for this discussion, FDA has voiced there should be consideration to support multiple layers of safety regarding tissue donation. For example, in deceased donation, behavioral history is sourced from someone other than the donor so screening for risks should be optimized and using these questions can aid in identifying risk where, otherwise, it could be missed. Child donors of tissues include: ocular, cardiac tissue (heart valves, conduits), and juvenile cartilage. • PHS Guideline for Reducing Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Hepatitis B Virus, and Hepatitis C Virus Transmission Through Organ Transplantation. Public Health Reports, July–August 2013, Volume 128. “As with the 1994 PHS guidelines, the recommendations relate to adult and pediatric donors who are living or deceased, as well as transplant candidates and recipients. This guideline is not intended to assess infectious risks beyond HIV, HBV, and HCV.” The PHS Guideline resulted in recommendations from a systematic review of the best evidence available to identify donor characteristics related to increased risk for HIV, HBV, and HCV. The search for evidence included tissue donor populations: Page 272 at “Topic I: Probability of transmission of HIV, HBV, or HCV through organ transplantation (Key Questions 1 and 52)” “Key Question 1: What are the prevalence and incidence rates of HIV, HBV, and HCV Scott A Brubaker Page 5 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening pathogens among potential organ donors?” “Ultimately, the search comprised potential deceased and living organ donors, potential tissue donors, and the U.S. general population.” Page 275 at “Topic II: Methodology to better estimate donor infection with HIV, HBV, or HCV (Key Questions 3, 4, and 5)” “Given the paucity of data evaluating behavioral and nonbehavioral risk factors for HIV, HBV, and HCV in potential organ donors, we also searched for studies meeting inclusion criteria in the following populations: • tissue donors • blood donors • general population…” Page 251 “Donors who meet one or more of the following 11 criteria should be identified as being at increased risk for recent HIV, HBV, and HCV infection. Each factor listed reflects increased risk of all three pathogens as an aggregate, as there is overlap of associated risk, even though each factor does not convey risk from all pathogens equally. The first six risk factors address sexual contact; the definition of “had sex” refers to any method of sexual contact, including vaginal, anal, and oral contact: (bullet #10) • People who have been in lockup, jail, prison, or a juvenile correctional facility for more than 72 consecutive hours in the preceding 12 months” This is the first reference where a donor screening criterion uses the term “juvenile correctional facility.” CDC occasionally issues reports on “juvenile correctional facilities” in regard to data on communicable disease, especially occurrence of certain sexually transmitted infections. See “CDC Reports” further below. The report’s assessment of quality of evidence from publications that relate to increased risk for HIV, HBV and HCV, included “inmates” and “risk factors in children” as behavioral risk factors, and nonbehavioral risk factors included “children” and “age or year of birth.” These risk factors are reviewed here and pertinent text highlighted in blue: HIV Behavioral risk factors - Pages 276 and 277 “5. Inmates. This review found very low-quality evidence from a single study to suggest an association between being incarcerated and having HIV (Appendix C). The 1994 PHS guideline identified being an inmate of a correctional system as a risk factor for HIV. No studies that examined the association between “present” incarceration and infection were identified. However, one study examined and did not identify an association between lifetime history of incarceration as reported by next of kin with HIV infection in potential corneal donors. 6. Risk factors in children. No studies were identified on behavioral risk factors for HIV in children, or on the risk of infection from mothers who engage in those risk behaviors. While a body of literature exists on vertical transmission as a mode of hepatitis or HIV transmission, this body of literature lacks the evidence to assess the 1994 PHS guidelines criteria as risk factors.” Nonbehavioral risk factors – Pages 283 and 284 3. Children. This literature review did not identify any studies regarding the nonbehavioral risk factors, listed previously, in relation to children or children of mothers who engage in those nonbehavioral risk factors. 8. Demographic factors. Scott A Brubaker Page 6 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening b. Age or year of birth. This review found very low-quality evidence to suggest a relationship between age and having HIV (Appendix D). Studies assessed different age ranges, complicating comparison. One study that conducted a multivariate analysis found adults aged 18–30 years had increased HIV prevalence. Another study that conducted a univariate analysis found higher HIV prevalence in adults aged 25–40 years compared with younger people aged 15–24 years with a large effect size. A third study found increased prevalence among adults aged 35–44 years. HBV Behavioral risk factors – Page 279 “5. Inmates. This review found very low-quality evidence to suggest an association between recent or past incarceration and having HBV (Appendix C). The 1994 PHS guidelines identified being an inmate of correctional systems as a risk factor for HIV. No studies examined the association between present incarceration and HBV infection. The search did identify studies that examined the association between recent or lifetime history of incarceration. A history of incarceration was associated with HBV in three of four studies. In the general population, imprisonment within the last six months was associated with recent HBV infection in univariate but not multivariate analysis. Incarceration was also significantly associated with HBV in a univariate analysis among psychiatric inpatient veterans and among college students incarcerated for at least 24 hours. A history of incarceration as reported by next of kin was not associated with HBV in potential corneal donors. 6. Risk factors in children. We identified no literature on any behavioral risk factors in children, or on the risk of infection from mothers who engage in those risk behaviors. While a body of literature exists on vertical transmission as a mode of hepatitis or HIV transmission, this body of literature lacks the evidence to assess the 1994 PHS guidelines criteria as risk factors.” Nonbehavioral risk factors – Pages 285 and 286 3. Children. We identified no studies regarding the nonbehavioral risk factors, listed previously, in relation to children or children of mothers who engage in those nonbehavioral risk factors. 8. Demographic factors. b. Age or year of birth. This review found very low quality evidence to suggest age as a risk factor for HBV (Appendix D). Studies assessed different age ranges, thereby complicating the comparison. One general population study found an increased risk of HBV in individuals > 60 years of age in a multivariate analysis. The remaining studies were in demographic or socioeconomic subpopulations. One study of college students found an association with increased mean age in a multivariate analysis while a study of psychiatric inpatient veterans did not. In univariate analyses, increased prevalence was associated with age > 35 years among embalmers in high-prevalence urban areas with a large effect size and age < 20 years among Korean-American churchgoers, but not age ≥ 50 years among psychiatric inpatient veterans in a multivariate analysis. In another study of Korean-American churchgoers, lower prevalence was found in people < 49 years of age. The last study comprising Asian Americans did not find any association between age and HBV. HCV Behavioral risk factors – Page 281 “5. Inmates. This review found low-quality evidence to support incarceration as a risk factor for HCV (Appendix C). The 1994 PHS guidelines identified being an inmate of a correctional system as a risk factor for HIV. We identified no studies that examined the association between present incarceration and HCV infection. The searches did, however, identify studies that examined the association between recent or lifetime history of incarceration. A history of incarceration was associated with HCV in four of five studies. One blood donor study found that incarceration for Scott A Brubaker Page 7 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening more than three days was an independent risk factor, while another study found no association once adjusting for confounding by IDU. In addition, having been arrested was associated with HCV infection in a univariate analysis of a general population sample. A history of incarceration, as reported by next of kin, was not associated with HCV infection in potential corneal donors. 6. Risk factors in children. The literature review did not identify any behavioral risk factors in children or the risk of infection from mothers who engage in those risky behaviors. While a body of literature exists on vertical transmission as a mode of hepatitis or HIV transmission, this body of literature lacks the evidence to assess the 1994 PHS guidelines criteria as risk factors.” Nonbehavioral risk factors – Pages 288, 290 3. Children. No studies were identified in the literature regarding the nonbehavioral risk factors, listed previously, in relation to children or children of mothers who engage in those nonbehavioral risk factors. 8. Demographic factors. b. Age or year of birth. This review found very low-quality evidence associating age and HCV (Appendix D). Studies assessed different age ranges, thereby complicating comparison. An organ donor study found that HCV infection was associated with older median age. One blood donor study associated HCV with older mean age while the other did not. In general population studies, HCV was associated with increased mean age and decade of birth (with people born from 1940 to 1959 having the highest prevalence), but not age <50 years or age < 60 years. The PHS Guideline covers this in Figure 14: “Behavioral and nonbehavioral characteristics associated with HIV, HBV, or HCV identified by low- to high-quality evidence from a systematic review of the literature regarding the risks of transmitting HIV, HBV, and HCV through organ transplantation.” An age range is listed twice that could be applicable to age 12 years and below but the behavior is “age at first sexual intercourse”: Type of Infection Behavioral characteristics HIV Age ≤ 18 years at first sexual intercourse HCV Age ≤ 18 years at first sexual intercourse Having had sexual intercourse is not a consideration related to placement in a juvenile correctional facility (aka “juvenile detention”), lock up, jail or prison. Other questioning on the Uniform DRAI for a donor ≤ 12 years old is used to assess risk associated with being involved in a sexual act, and sexually transmitted infections: 26. Did she/he* EVER have an infection such as syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, or genital ulcers, herpes, or genital warts? If yes, 26a. What was it? 26b. How was it treated? 26c. How long ago? 27. Do you have any reason to believe that she/he* was EVER involved in a sexual act, or was sexually assaulted or abused? If yes, 27a. How long ago? The following questions are about any person with whom sexual contact occurred. (6 to 7 more specific risk-associated questions would be asked) Figure 14 additionally lists “inmates” under behavioral characteristics: Type of Infection Behavioral characteristics HCV Inmates Risk evaluated for “inmates” referred to in the PHS Guideline only identified adult inmates as Scott A Brubaker Page 8 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening having increased risk. Conclusion: Recommendations from the PHS Guideline (2013) included analysis of publications involving the tissue donor population, and the recommendations apply to “pediatric donors.” Evaluation of risks for HIV, HBV, and HCV included “children.” The exhaustive reviews of literature (aka “best evidence available”) performed to create the PHS Guideline suggest it is not warranted to screen children newborn to 12 years (inclusive) for increased risk associated with HIV, HBV, or HCV in relation to placement in a juvenile correctional facility (aka “juvenile detention”), lock up, jail or prison. “Inmates” reported here apply only to adults and the literature review identified one possible behavioral risk factor for HIV and HCV: “age at first sexual intercourse.” The child donor’s involvement ‘ever’ in a sexual act is addressed by other questions on the Uniform DRAI for a donor ≤ 12 years old. CTO Guidance and Standards - Canada “Guidance Document For Cell, Tissue And Organ Establishments, Safety of Human Cells, Tissues and Organs for Transplantation. Ministry of Health, Health Canada 6-18-2013.” This guidance makes multiple references to Annex E of the standards below (CAN/CSA-Z900.112) as a requirement when screening cell, tissue, and organ donors. “CAN/CSA-Z900.1-12, Cells, tissues, and organs for transplantation: General requirements, April 2013.” See Annex E (normative) “Factors and behaviours associated with a higher risk of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)” describes at “E.1: The assessment of donors 11 years of age or older shall include the following risk factors and risk behaviours associated with HIV, HBV, and HCV: (relevant part only) (f) persons who have been in juvenile detention, lock up, jail, or prison for more than 72 consecutive hours in the preceding 12 months;” and at this part, this risk is excluded for children less than 11 years of age E.2 The assessment of donors less than 11 years of age shall include the following risk factors and risk behaviours associated with HIV, HBV, and HCV: [the listing at (f) above is not included] Information provided by a representative of Health Canada reveals there is a criminal justice act that governs the age at which a child can be held criminally responsible for their actions. Provincial child welfare and mental health legislation would address serious criminal behaviour in children under the age of twelve. Any methods used to address a child's behaviour under twelve would not involve correctional services, therefore the reference to juvenile detention is not appropriate for this age group in Canada. The YCJA (Youth Criminal Justice Act) governs the application of criminal and correctional law to those 12 years old or older, but younger than 18 at the time of committing the offence (Section 2 of the YCJA). Youth aged 14 to 17 may be tried and/or sentenced as adults under certain conditions. The Criminal Code of Canada, section 13, states "No person shall be convicted of an offence in respect of an act or omission on his or her part while that person was under the age of twelve years." References: Youth Criminal Justice Act, S.C. 2002, c.1 (Feb19, 2002) http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/Y-1.5/index.html Scott A Brubaker Page 9 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening Youth Criminal Justice Act Background http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/yj-jj/ycja-lsjpa/back-hist.html Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46) http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/ This Code contains a definition of "prison" as: « prison » “prison” includes a penitentiary, common jail, public or reformatory prison, lock-up, guard-room or other place in which persons who are charged with or convicted of offences are usually kept in custody; Conclusion: The recommendations from Health Canada indicates a donor “less than 11 years of age” is not expected to be screened for risk related to having been in juvenile detention (aka “juvenile correctional facility), lock up, jail, or prison in the past 12 months, however, a donor age 12 years of age should be screened for this risk. Additional references can be found via Canadian Criminal Code (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46) and the Youth Criminal Justice Act, S.C. 2002, c.1. Rates of HIV, HBV and/or HCV in this population are not reported. Relevant OJJDP Reports The Child DRAI Work Group was aware of information provided on the website of the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) (http://www.ojjdp.gov/). This site allows specific search functions to determine why the population age 12 and under could be detained or placed in a facility. To perform a useful search, specific parameters should be selected based on the Glossary: http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/asp/glossary.asp The following terms seem relevant and the terms in blue text were used to query for age “12 or younger:” According to the Glossary: Facility self-classification Locks Most serious offense Placement status Facility self-classification: Detention Center: a short-term facility that provides temporary care in a physically restricting environment for juveniles in custody pending court disposition and, often, for juveniles who are adjudicated delinquent and awaiting disposition or placement elsewhere, or are awaiting transfer to another jurisdiction. Shelter: a short-term facility that provides temporary care similar to that of a detention center, but in a physically unrestricting environment. Includes runaway/homeless shelters and other types of shelters. Reception/Diagnostic Center: a short-term facility that screens persons committed by the courts and assigns them to appropriate correctional facilities. Scott A Brubaker Page 10 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening Long-term secure facility: a specialized type of facility that provides strict confinement for its residents. Includes training schools, reformatories, and juvenile correctional facilities. Ranch/Wilderness Camp: a long-term residential facility for persons whose behavior does not necessitate the strict confinement of a long-term secure facility, often allowing them greater contact with the community. Includes ranches, forestry camps, wilderness or marine programs, or farms. Group Home: a long-term facility in which residents are allowed extensive contact with the community, such as attending school or holding a job. Includes halfway houses. Boot Camp: a secure facility that operates like military basic training. There is emphasis on physical activity, drills, and manual labor. Strict rules and drill instructor tactics are designed to break down youth's resistance. Length of stay is generally longer than detention but shorter than most long-term commitments. Other: includes facilities such as alternative schools and independent living, etc. Locks: Locks indicated: facility indicated that juveniles are restricted within the facility or its grounds by locked doors, gates, or fences some or all of the time. No locks indicated: facility has not indicated that juveniles are restricted within the facility or its grounds by locked doors, gates, or fences; facilities that do not rely on locks for security are also known as staff secure. Unknown Most serious offense: Delinquent/criminal offense: An offense that is considered illegal for adults. o Person offenses: Offenses against persons as detailed below. Aggravated assault: An actual, attempted or threatened physical attack on a person that 1) involves the use of a weapon of 2) causes serious physical harm. Includes attempted murder. (For assaults with less than serious injury without a weapon, see Simple assault.) Criminal homicide: Causing the death of a person without legal justification. (For attempted murder/manslaughter, see Aggravated assault.) Robbery: Actual or attempted unlawful taking of property in the direct possession of a person by force or threat of force. Includes purse snatching with force. (For purse snatching without force, see Theft.) Simple assault: An actual, attempted or threatened physical attack on a person that causes less than serious physical harm without a weapon. Includes non-physical attacks causing fear of an attack. Violent sexual assault: Actual or attempted sexual intercourse or sexual assaults against a person against her or his will by force or threat of force. Includes incest, sodomy, and sexual abuse by a minor against another minor. (See also Non-violent sex offense.) Other person offenses: Person offenses not detailed above. Examples include: harassment, coercion, kidnapping, reckless endangerment, etc. o Property offenses: Offenses against property as detailed below. Scott A Brubaker Page 11 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening o o o Arson: Actual or attempted intentional damaging or destroying of property by fire or explosion, without the owner’s consent. Auto theft: Actual or attempted unauthorized taking or use of a motor vehicle, intending to deprive the owner of it temporarily or permanently. Includes joyriding and grand theft auto. Burglary: Actual or attempted unlawful entry or attempted entry of a building, structure, or vehicle with intent to commit larceny or another crime. Includes breaking and entering and household larceny. Theft, non-household larceny: Actual or attempted unlawful taking or attempted taking of property (other than an automobile) from a person without force or deceit. Includes shoplifting and purse snatching without force. (For purse snatching with force, see Robbery. For theft of an automobile, see Auto theft. For household larceny, see Burglary. For theft using deceit, see Other property offenses.) Other property offenses: Property offenses not detailed above. Examples include: vandalism, trespassing, selling stolen property, possession of burglar’s tools, fraud, etc. Drug offenses: Offenses involving drugs or narcotics as detailed below. Trafficking: Actual or attempted making, selling, or distributing of a controlled or illegal drug or substance. Other drug-related offenses: Drug offenses other than trafficking. Examples include drug possession or use, possession of drug paraphernalia, visiting a place where drugs are found, etc. Public order offenses: Offenses against the public order as detailed below. Alcohol or drugs, driving under the influence: Driving or operating a motor vehicle while under the influence of alcohol or other drug or controlled substance. Weapons: Actual or attempted illegal sale, distribution, manufacture, alteration, transportation, possession, or use of a deadly or dangerous weapon or accessory. Other public order offenses: Public order offenses not detailed above. Examples include obstruction of justice (escape from confinement, perjury, contempt of court, etc), non-violent sex offenses, cruelty to animals, disorderly conduct, traffic offenses, etc. Technical violations: Violations of probation, parole, or valid court orders; acts that disobey or go against the conditions of probation or parole. Examples include: failure to participate in a specific program, failure to appear for drug tests or meetings, and failure to pay restitution. Placement status: Committed: Includes juveniles in placement in the facility as part of a courtordered disposition. Committed juveniles may have been adjudicated and disposed in juvenile court or convicted and sentenced in criminal court. Detained: Includes juveniles held prior to adjudication while awaiting an adjudication hearing in juvenile court, as well as juveniles held after adjudication while awaiting disposition or after adjudication while awaiting placement elsewhere. Also includes juveniles awaiting transfer to adult criminal court, or awaiting a hearing or trial in adult criminal court. Scott A Brubaker Page 12 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening Diversion: Includes juveniles sent to the facility in lieu of adjudication as part of a diversion agreement. This link was used to perform queries: http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/asp/selection.asp Results of specific queries for 2011: 1st Query: 2011, 12 or younger, committed, sexual assault, drug trafficking, other drug, detention center, long-term secure, locks. The total = 10 2nd Query: 2011, 12 or younger, detained, sexual assault, drug trafficking, other drug, detention center, long-term secure, locks. The total = 53 3rd Query: 2011, 12 or younger, committed, detention center, long-term secure, locks. The total = 84 4th Query: 2011, 12 or younger, detention center, long-term secure. The total = 463 5th Query: 2011, 12 or younger, locks. The total = 658 The following article provides insight into how some states handle sentencing children “under age 18” to an adult correctional facility (prison or jail) circa 1995: “Offenders Under Age 18 in State Adult Correctional Systems: A National Picture-February 1995.” Special Issues in Corrections, U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections Information Center, Longmont, Colorado This report describes “At present, the youngest age at which an offender may be sentenced to the state’s adult correctional system is 12 years, in Washington State. The most common cutoff ages are 14 and 16 years. And, at “Table I. Juvenile Offender Age Limits and DOC Populations,” Nevada reports the youngest age (8) at which an offender is eligible for “trial in adult court,” however, some states describe “no limit.” Note that in Nevada, for age 8 years, an applicable crime would be for murder, attempted murder, assault with a deadly weapon, causing substantial injury, kidnapping, or armed robbery. A link provided by FDA is this Statistical Briefing Book circa 2013: http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/structure_process/qa04102.asp?qaDate=2013 It describes: “In the majority of states, the upper age is 17 and the lower age is not specified for delinquency and status jurisdiction.” On the table for 2013, the lowest age noted for “delinquency jurisdiction” and for “status jurisdiction” was age 6. Questions on the Uniform DRAI for a donor ≤ 12 years old include assessment of risk associated with sexually transmitted infections, involvement in a sex act, and drugs: 16. Was she/he* EVER given or did she/he* use drugs, such as steroids, cocaine, heroin, amphetamines, or anything NOT prescribed by her/his* doctor? If yes, 16a. What was it? 16b. How often and how long was it used? 16c. When was it last used? 16d. Were needles used? If no, 16d(i). How was it taken? Scott A Brubaker Page 13 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening 26. Did she/he* EVER have an infection such as syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, or genital ulcers, herpes, or genital warts? If yes, 26a. What was it? 26b. How was it treated? 26c. How long ago? 27. Do you have any reason to believe that she/he* was EVER involved in a sexual act, or was sexually assaulted or abused? If yes, 27a. How long ago? The following questions are about any person with whom sexual contact occurred. (6 to 7 more specific risk-associated questions would be asked) However, for deceased donation, behavioral history is sourced from someone other than the donor so there should be consideration to optimize screening for risks and this could be handled by additional questioning. The following two articles were provided and each offers relevant information when making a decision about screening (part) of this age group for risks related to detainment in a juvenile correctional facility, lock up, jail or prison in the past 12 months: • Sexual Victimization in Juvenile Facilities Reported by Youth, 2012. National Survey of Youth in Custody, 2012. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. June 2013, NCJ 241708. This is report on the second National Survey of Youth in Custody (NSYC-2) in 273 state-owned or -operated juvenile facilities and 53 locally or privately operated facilities that held adjudicated youth under state contract. It was administered to 8,707 youth sampled from at least one facility in every state and the District of Columbia. They completed the survey on sexual victimization and passed editing and consistency checks. The Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003 (P.L. 10879; PREA) requires the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) to carry out a comprehensive statistical review and analysis of the incidents and effects of prison rape for each calendar year. This report fulfills the requirement under Sec.4(c)(2)(B)(ii) of the act to provide a list of juvenile correctional facilities according to the prevalence of sexual victimization. (relevant) Terms and definitions Sexual victimization—any forced sexual activity with another youth (nonconsensual sexual acts and other sexual contacts) and all sexual activity with facility staff. Highlights of this report include (note, this is not all-inclusive): Prevalence of sexual victimization An estimated 9.5% of adjudicated youth in state juvenile facilities and state contract facilities (representing 1,720 youth nationwide) reported experiencing one or more incidents of sexual victimization by another youth or staff in the past 12 months or since admission, if less than 12 months. About 2.5% of youth (450 nationwide) reported an incident involving another youth, and 7.7% (1,390) reported an incident involving facility staff. An estimated 3.5% of youth reported having sex or other sexual contact with facility staff Scott A Brubaker Page 14 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening as a result of force or other forms of coercion, while 4.7% of youth reported sexual contact with staff without any force, threat, or explicit form of coercion. Among state juvenile facilities, the rate of sexual victimization declined from 12.6% in 2008-09 (when the first survey was conducted) to 9.9% in 2012. The decline in state facilities was linked to staff sexual misconduct with force (declining from 4.5% of youth in 2008-09 to 3.6% in 2012) and staff sexual misconduct without force (declining from 6.7% to 5.1%). Facility Rankings Youth held in state-owned or -operated facilities reported higher rates of staff sexual misconduct (8.2%) than those held in locally or privately operated facilities (4.5%). State-Level Rates Four states (Georgia, Illinois, Ohio, and South Carolina) had high rates, based on the lower bound of the 95%-confidence interval of at least 35% higher than the national average. Each of these states had an overall sexual victimization rate exceeding 15%, which was primarily due to high rates of staff sexual misconduct. Circumstances surrounding the incident About 67.7% of youth victimized by another youth reported experiencing physical force or threat of force, 25.2% were offered favors or protection, and 18.1% were given drugs or alcohol to engage in sexual contact. Most youth-on-youth victims reported more than one incident (69.6%). An estimated 37.2% reported more than one perpetrator. Among the estimated 1,390 youth who reported victimization by staff, 89.1% were males reporting sexual activity with female staff and 3.0% were males reporting sexual activity with both male and female staff. In comparison, males comprised 91% of adjudicated youth in the survey and female staff accounted for 44% of staff in the sampled facilities. Most victims of staff sexual misconduct reported more than one incident (85.9%). Among these youth, nearly 1 in 5 (20.4%) reported 11 or more incidents. This appears at “Appendix 3. Items checked for extreme and inconsistent response patterns”: Items unrelated to reports of sexual victimization 1. Reported one of the following: ƒ. being admitted to the facility before turning age 8 • Victims of Childhood Sexual Abuse– Later Criminal Consequences. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice. Series: NIJ Research in Brief. Cathy Spatz Widom. March 1995. The subjects were 908 individuals who had been subjected as children to abuse (physical or sexual) or neglect, and whose cases were processed through the courts between 1967 and 1971. All were 11 years of age or younger at the time of the incident(s). This is the only reference in the article to age and no other correlation was noted in key findings regarding screening this age group for detainment in a correctional facility while a youth. Scott A Brubaker Page 15 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening Key findings: People who were sexually victimized during childhood are at higher risk of arrest for committing crimes as adults, including sex crimes, than are people who did not suffer sexual or physical abuse or neglect during childhood. However, the risk of arrest for childhood sexual abuse victims as adults is no higher than for victims of other types of childhood abuse and neglect. The vast majority of childhood sexual abuse victims are not arrested for sex crimes or any other crimes as adults. Compared to victims of childhood physical abuse and neglect, victims of childhood sexual abuse are at greater risk of being arrested for one type of sex crime: prostitution. For the specific sex crimes of rape and sodomy, victims of physical abuse tended to be at greater risk for committing those crimes than were sexual abuse victims and people who had not been victimized. What might seem to be a logical progression from childhood sexual abuse to running away to prostitution was not borne out. The adults arrested for prostitution were not the runaways identified in this study. Conclusion: The population 12 and younger in the US can be placed in locked, detention centers/facilities, and in some states, children can be placed in jail or prison due to lack of correctional facilities for juveniles. In the majority of states, the upper age is 17 and the lower age is not specified for delinquency and status jurisdiction (2013), however, the lowest age noted for delinquency and status jurisdiction was age 6. Crimes related to behaviors that might also increase risk for HIV, HBV, and HCV (sexual assault, drug trafficking, other drug) are very low numbers (2011) that support this as a rare occurrence. But, consideration of reports that reveal there can be sexual victimization that occurs while detained in a correctional facility could play a role in screening donors in this age group. A report (2013) described that sexual victimization while detained did not occur before turning age 8. The idea being considered is to screen for this risk if the donor age is from 6 to 12 years (inclusive), or 8 to 12 years (inclusive). Drug use, being involved in a sexual act, and history of STIs are covered in other questioning used in the Uniform DRAI for a donor ≤ 12 years old so it’s not clear how an additional query regarding detainment to a correctional facility can add value to screening for risk associated with HIV, HBV, and HCV. However, for deceased donation, behavioral history is sourced from someone other than the donor so there should be consideration to optimize screening for risks and this could be handled by additional questioning. Relevant CDC Reports The CDC periodically issues reports involving juvenile correctional facilities. This CDC report describes that few tuberculosis (TB) cases occur under age 18 in juvenile correction facilities and it provides a definition for such a facility that appears to coincide with all possible detention sites described in the OJJDP website’s Glossary: http://www.cdc.gov/TB/publications/slidesets/correctionalfacilities/d_link_text.htm "Juvenile correction facility: Public or private residential facility; includes juvenile detention centers, reception and diagnostic centers, ranches, camps, farms, boot camps, residential treatment centers, and halfway houses or group homes designated specifically for juveniles." Scott A Brubaker Page 16 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening It’s not clear if it can be assumed this definition fits all reports of juvenile correctional facilities issued by CDC. At the following link for STDs (i.e., syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea), CDC reports only on ages 12-18 related to juvenile correctional facilities: “2011 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance; STDs in Persons Entering Corrections Facilities” http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/corrections.htm Reports on risk for HIV, HBV or HCV in a juvenile correctional facilities are scarce and often dated: • “HIV and AIDS Risk Behaviors in Juvenile Detainees: Implications for Public Health Policy. Teplin LA, Mericle AA, McClelland GM, Abram KM. Am J Public Health. 2003 June; 93(6): 906–912.” This study had (1) a stratified random sample large enough to compare rates by gender, race/ethnicity, and age and (2) comprehensive measures of sexual and drug HIV and AIDS risk behaviors: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1447866/ Excerpts from this limited study: “Among males, even in the youngest age group (10–13 years), 62% to 76% had vaginal sex, used alcohol, or used marijuana. Among females aged 10 to 13, more than half were sexually active, more than 40% had vaginal sex, more than 80% used alcohol, and more than two thirds used marijuana. Our findings confirmed that HIV and AIDS risk behaviors are a substantial problem among detained youths, posing a challenge to the justice system and to the larger public health system. The rates found in our study are much higher than those in the general population and confirm prior findings of racial/ethnic differences. Ninety-five percent of our sample engaged in 3 or more risk behaviors reported in this brief; 65% reported 10 or more risk behaviors. Subjects may have exaggerated their behaviors or underreported them. Moreover, this study used only 1 site and pertains to only urban youths. Nevertheless, our data have important implications for research and public health policy.” • “Health Care for Youth in the Juvenile Justice System. American Academy Of Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence, Pediatrics 2011;128;1219.” “STIs/HIV Data from the CDC’s 2009 Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance Report demonstrated that youth in the juvenile detention system have among the highest rates of STIs (Table 2). Similar data were collected in another study that represented 12 juvenile correction facilities in 5 jurisdictions between 1996 and 1999. Because of unprotected sex with multiple partners, prostitution, or injection drug use, youth in correctional facilities are also at increased risk of HIV and hepatitis C virus infection. In addition, they are at risk of hepatitis B virus infection when the vaccination series is incomplete. High rates of STIs, alcohol and drug use, and lack of consistent condom use also contribute to increased risk of HIV infection. TABLE 2 STI Rates Among Incarcerated Adolescents Aged 12 to 18 Years, 2009 Disease Overall Positivity, % Female Male Chlamydia 14.8 6.6 Gonorrhea 3.9 1.0 Chlamydia data are from 83 juvenile detention facilities for women and 123 facilities for men. Gonorrhea data are from 71 juvenile detention facilities for women and 118 facilities for men.” This month, a Stakeholder Review Group member contacted experts in HIV (Dr. Irene Hall) and HBV\HCV (Dr. Fujie Xu) at CDC. They voiced they do not have data on the prevalence of HIV/HBV/HCV in Juvenile Correctional Facility populations with a focus on the Child DRAI age range of newborn to 12 yrs. For viral hepatitis, Dr. Xu described that HCV sexual Scott A Brubaker Page 17 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening transmission would be rare, and that HBV vaccination coverage is very high in this population, and that vertical transmission exists but it’s not related to jails or prisons for children. Via information garnered from NHANES (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm), no specific data from juvenile correctional facilities can be found for this age group. A survey covering 20032010 for HCV revealed no cases for children between 6-12 yrs old. Three states screen for HCV (unless a person opts out) but this only covers an older population (it can be ≈ 15%) but data for children has not been identified. Dr. Hall concluded that HIV is rare in children and those who contract it usually occur via perinatal exposure. Conclusion: There is only STI data (i.e., chlamydia and gonorrhea) beginning with age 12 that relates to juvenile correction facilities and a relationship to increased risk for HIV, HBV, and HCV. Risk associated with sexual acts and STIs are already covered by other questioning on the Uniform DRAI for a Donor ≤ 12 years old. It’s not clear how an additional query regarding detainment to a correctional facility can add value to screening for risk associated with HIV, HBV, and HCV. Relevant References Regarding Development of this Donor Screening Question Summary of Focus Group Discussions of Donor Screening Questions for Structure, Content and Comprehension. Sharyn L. Orton, Ph.D., Scientist Holland Laboratory, Transmissible Diseases Laboratory and Victoria J. Virvos, M.Ed., Consultant Enlightening Enterprises, Richmond, VA (circa 1999?) Page 12 This reference provides the first indication when a blood donor history questionnaire included language relevant to “juvenile detention.” This report, using a focus group review approach, evaluated a version of a uniform donor history questionnaire (UDHQ) for blood donors being developed by a multi-organizational task force led by the AABB. A passage is reproduced here where individual questions are evaluated in the report: # 16: UDHQ: "In the past 12 months, have you been in jail or prison? " Focus group discussion: Participants gave some thought to changing to "incarcerated in jail or in prisons," to clarify residence. The high school age participants wanted to know if this included county lock-up and/or juvenile hall (because exposure risk can occur there as well). All participants wanted to know if this was for a specific time frame. They were informed of the 72 hour limit. Their recommendations were (1) add lock-up and/or juvenile hall, and (2) add the time period to the end of the question (although there was some concern about the length of the question). Participant recommendation (HS group): " In the past 12 months, have you been in juvenile hall, lock-up, jail or prison?" or, "In the past 12 months, have you been in juvenile hall, lock-up, jail or prison for more than 72 hours? In this report’s 4 Tables that each represent a different focus group, the first two show an age range of 17-20, and the third and fourth groups list the youngest participants as age “<18” and for educational level, all 5 of those <18 were (in) “High school.” In the Conclusion, “Information obtained from conducting these focus groups contributed valuable information and suggestions regarding wording of targeted donor history questions for better donor comprehension.” Of the 10 references listed, only two were relevant by titled and reviewed for any information on “juvenile hall” or “juvenile detention” but nothing was found. These reference articles in the report were reviewed: “6. Kolins J, Silvergleid AJ. Creating a Uniform Donor Medical History Questionnaire. Scott A Brubaker Page 18 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening Transfusion, 1991, 31;4:349-354” and “10. Orton SL, Virvos VJ, Williams AE. Validation of donor-screening questions: structure, content, and comprehension. Transfusion, 2000, 40: 14071413.” Conclusion: The use of “juvenile hall” in an early version of the blood UDHQ as it was being developed and evaluated does not apply to screening children newborn to 12 years (inclusive) for increased risk associated with HIV, HBV, or HCV. The age group is too young to donate blood or blood components, and an age group younger than “high school” age was not included in the intent of the development of the question. • Cognitive Interview Evaluation of the Blood Donor History Screening Questionnaire Results of a study conducted August-December, 2001. Paul Beatty, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Interviewing Team: Paul Beatty, Kristen Miller, Barbara Wilson, Karen Whitaker, Joel Kennet) (circa 2002) Pages 39 and 40 (the pages are not numbered) This report, using cognitive interviewing techniques, evaluated a revised version of the uniform donor history questionnaire (UDHQ) for blood donors described immediately above. In Methods, it describes: “The basic procedure of a cognitive interview is that a questionnaire-design specialist administers the questionnaire and adds intensive probes. These probes are chosen to provide insight into problems with comprehension, difficulty recalling necessary information, potential response biases, answer categories that are inappropriate, and so on.” A total of 35 participants, divided into 3 Rounds, were interviewed for this project. Participants in Round 3 were selected to fill in gaps in previous recruitments, with a particular focus on young donors (e.g., six were 21 or younger). Here is the report on discussion for this question: “26. Been in juvenile hall, lockup, jail, or prison? Round 1: No participants had been in this situation during the reference period of the question. Two participants had been in earlier years – one for an alcohol related offense, and the other in juvenile hall for two weeks during freshman year in high school. The latter participant erroneously responded yes to the question, losing track of the time frame. (This is the same participant who provided false positives for Q23 and Q24, probably due to questionnaire formatting). Some participants thought of lockup, jail, and prison as basically the same thing. More commonly, participants viewed them as ranging from places for overnight detention, to somewhat longer stays, to doing hard time. The terms seem to cover all the bases – although a few participants questioned whether “lockup” was appropriate since they viewed this as a low risk place. Round 2: No participants answered yes. A few had been temporarily detained in earlier years (e.g., for drunk driving, and a hunting violation). The interpretations of the key terms were consistent with those in the previous round. One participant raised an interesting issue: she had never been incarcerated, but had once worked for a company that delivered to prisons. While she never had to go inside a prison herself, she thought that her answer should have been yes if she had made such a delivery. Similarly, she thought that anyone who visited someone in jail should also answer yes to this question. This may not be the intent of the question, but the errors from such interpretations would only be false positives. Round 3: All eleven participants answered no. Most had never been in any of these for any reason, although one participant mentioned stints in juvenile hall (1996) and lockup Scott A Brubaker Page 19 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening (1998). Most participants saw these institutions as differing by degree, i.e., with prison being more serious than jail. One participant works in juvenile detention, but assumed that the question referred to incarceration only (based on information she saw in the informational materials). But she also questioned whether that made sense, since people come into contact with the same individuals either way. She also wondered whether group probation homes should count, since they house some of the same people who appear in lockup or juvenile detention. A general comment: juvenile hall is only relevant to a very small number of people (those who were juveniles within the past year). The only problem with leaving this in the question is that it won’t make much sense to older (age 20 +) participants. There may be a tendency to confuse them and create some false positives. This is probably not a major problem, but it does add to the burden of the item. Given that juvenile hall applies to a small number of people, may be a relatively safe and supervised place, and that such offenses may be captured by “lockup, jail, and prison” anyway, it is unclear whether this is worth keeping in the question. Recommendation: Consider whether juvenile hall is really necessary. Supplement the definitions available to blood center staffs regarding whether visitation in these facilities should count, and possibly whether probation houses count as detention facilities.” Conclusion: The use of “juvenile hall” in a later version of the blood UDHQ as it was being evaluated, does not apply to screening children newborn to 12 years (inclusive) for increased risk associated with HIV, HBV, or HCV. The age group is too young to donate blood or blood components. Additionally, there is a general comment suggesting that: “juvenile hall…may be a relatively safe and supervised place.” Except for one participant’s self description of working “in juvenile detention,” it’s not clear how a decision was made to change “juvenile hall” to “juvenile detention” or the decision to keep the reference to “juvenile” in a final version of the blood DHQ. I can ask folks at AABB if they can shed some light on this. Other Relevant Publications – United States • “Detecting, Preventing, and Treating Sexually Transmitted Diseases Among Adolescent Arrestees: An Unmet Public Health Need. Am J Public Health. 2009 June; 99(6): 1032-1041” The article contains some data but it does not cover our focus age group. An interesting description of the juvenile justice system and part of the article’s conclusion is provided below. “In the United States, chlamydia and gonorrhea rates continue to be highest among adolescents and young adults in the general population. In 2006 the highest age-specific rate of reported gonorrhea cases in women was among adolescents aged 15-19 years (648 per 100,000); for men the highest rate was among those aged 20-24 years (454 per 100, 000). The highest age-specific rates of reported chlamydia cases were found among the same groups of adolescent girls (2862 cases per 100,000) and men (857 per 100,000). An estimated 60% of annual incident gonorrhea and 54% of incident chlamydia cases are among youths and young adults aged 15-24 years. A recent national study of chlamydia prevalence found that 4.6% of adolescent girls aged 14-19 years were infected, the highest proportion of any age group. Among young women aged 16-24 years entering the National Job Training Program (which targets high-risk, low-income youths), the median chlamydia prevalence within states was 13.1% (range 4.9% to 20.0%); among adolescent boys, the median chlamydia prevalence was 7.9% (range 1.8% to 12.4%).” Scott A Brubaker Page 20 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening “The juvenile justice system focuses primarily on public safety; it is neither organized to routinely identify or treat infectious diseases nor oriented toward increasing access to preventive health care. The following is a basic description of how juvenile arrests (2.1 million in 2005, including all arrests of persons under age 18 years) are processed, illustrating how most offenders are released from custody early in the process rather than being detained or incarcerated. “The first juvenile justice system stage after arrest is intake. At this time, juvenile probation officers can dismiss the case, process it informally (e.g., warning the youth or calling parents), or bring the case before a judge. In some jurisdictions, centralized intake facilities such as juvenile assessment centers perform this function. Most delinquency cases (57%) are formally convicted in juvenile court; the remainder are dismissed, diverted to community programs, or processed informally. For nondiverted adolescent offenders, a prosecutor decides whether to detain the youth in a secure facility before adjudication; only 20% of these youths are detained. Convicted youths may be placed on juvenile probation (62%) or, in more serious cases, placed in a secure residential facility. Probation conditions may include a curfew, attending school, or participating in drug treatment or other services. Some convicted youths are incarcerated in residential facilities (with a range of security levels), with some health care services available. At discharge, youths are typically placed on 3 to 12 months of aftercare supervision; this includes counseling, education, electronic monitoring, treatment, or community service referrals. Juveniles violating aftercare conditions can have their aftercare status revoked and be returned to a secure institution. Although, in principal, youths placed in the custody of juvenile justice agencies receive a medical evaluation and indicated care, the scope and quality of this care varies considerably.” “Conclusion The value of early detection and routine surveillance of infectious diseases for identifying highrisk populations and geographic distributions of infections is well established. Adolescent offenders at all stages of the juvenile justice system are at high risk of STDs, yet screening mainly occurs in detention or correctional facilities. Only a small percentage of young offenders are ever incarcerated or detained for any period of time. Most are quickly released back into the community after arrest, which suggests the need for screening protocols at the front end of the juvenile justice system. Public health officials have called for systematic collection of STD data in juvenile justice populations, while also recognizing that many barriers exist to developing and implementing such surveillance programs.” Conclusion: This article helps understand why data is not available for the age group of our focus. The STDs included here are covered by other questioning on the Uniform DRAI for a donor ≤12 years old. Commission Directive - European Union • “COMMISSION DIRECTIVE 2006/17/EC of 8 February 2006 implementing Directive 2004/23/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards certain technical requirements for the donation, procurement and testing of human tissues and cells.” See ANNEX I: 1. Deceased Donors 1.1. General criteria for exclusion No criteria found for juvenile detention, juvenile correctional facilities, lock up, jail, or prison. Scott A Brubaker Page 21 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening No criteria found in specific direction for child donors: 1.2. Additional exclusion criteria for deceased child donors 1.2.1. Any children born from mothers with HIV infection or that meet any of the exclusion criteria described in section 1.1 must be excluded as donors until the risk of transmission of infection can be definitely ruled out. (a) Children aged less than 18 months born from mothers with HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C or HTLV infection, or at risk of such infection, and who have been breastfed by their mothers during the previous 12 months, cannot be considered as donors regardless of the results of the analytical tests. (b) Children of mothers with HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C or HTLV infection, or at risk of such infection, and who have not been breastfed by their mothers during the previous 12 months and for whom analytical tests, physical examinations, and reviews of medical records do not provide evidence of HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C or HTLV infection, can be accepted as donors. Conclusion: Risk related to having been in juvenile detention (aka “juvenile correctional facility), lock up, jail, or prison is not a donor screening criterion in the relevant EU Directive for donors (of any age) of tissues and cells. Australian Order & Guide (Therapeutic Goods Administration) • “Therapeutic Goods Order No. 88 Standards for donor selection, testing, and minimising infectious disease transmission via therapeutic goods that are human blood and blood components, human tissues and human cellular therapy products. 20 May 2013.” The only reference to a child donor is here: “PART 3 – SPECIFIC REQUIREMENTS 9. Requirements in relation to the medical and social history of prospective donors (9) To address the possible vertical transmission of infectious agents in infant donors of less than 18 months old, or up to 6 months beyond breast feeding, whichever is the greater time, the birth mother must also be evaluated for high risk behaviour against the criteria set out in items (a) to (e), and (j), (k), (l), (p) and (r) of Table 1. If the birth mother meets any of those criteria, ineligibility periods set out in column 2 of Table 1 for those criteria in respect of the birth mother must be observed in relation to the child donor.” And this is the reference to prison: “Table 1: Minimum medical and social criteria required to determine donor risk of exposure to infectious disease and ineligibility periods” Column 1: Donor medical and social history criteria (l) An inmate of a prison. Column 2: Period of ineligibility, and related testing and notification requirements, prior to donation (donors of products for allogeneic use only) Ineligible for 12 months from date of release (when imprisoned for a consecutive period of 72 hours or more). Australian Regulatory Guidelines for Biologicals, Appendix 4 – Guidance on TGO 88 – Scott A Brubaker Page 22 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening Standards for donor selection, testing and minimising infectious disease transmission via therapeutic goods that are human blood and blood components, human tissues and human cellular therapy products. Version 2.0, February 2014 These guidelines do not mention “prison” and offer only this for child donors: “Subsection 9(9) Vertical transmission of infectious disease This subsection provides specific criteria that apply to the mothers of infant donors in order to reduce the risk of vertical transmission of disease via placenta or lactation. Compliance with this clause should also consider circumstances where an infant donor may have received milk from a donor milk bank, in which case the donor of the milk should also be assessed.” Conclusion: There is no description and there are no references provided to indicate a child donor newborn to age 12 (inclusive) should be screened for this risk criterion unless she/he was an inmate of a prison in the past 12 months. • “HIV/AIDS and STDs in Juvenile Facilities - Research Brief. U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. By Rebecca Widom and Theodore M. Hammett, April 1996” This reports on “The 1994 National Institute of Justice and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) survey” “Only 2 of the 73 systems that responded to the survey conduct man­datory HIV screening of all incoming juveniles (11 more systems screen pregnant girls). Most systems provide HIV, STD, and pregnancy testing on a voluntary basis and/or when juveniles exhibit clinical indications of disease or pregnancy.” There is no information provided below the age of 13: “Key findings: Although only about 1 percent of individuals diagnosed with AIDS between 1993 and 1994 were between 13 and 19 years old, many youths engage in high-risk behavior that puts them in danger of contracting HIV and STDs.” Part of article’s Conclusion: “Many juveniles in confinement have engaged in activities that place them at elevated risk for HIV and STDs. Nevertheless, HIV has not yet become as widespread as STDs among adolescents in detention centers and training schools.” Conclusion: There is no description that indicates a child donor newborn to age 12 (inclusive) is part of this report. Other Thoughts This exercise reveals the existence of more misinterpretation of intent regarding donor screening criteria created long ago (see comments sent to FDA by AATB regarding HDCFCs, dated August 2, 2013). It additionally strongly suggests the exhaustive review of behavioral risk and nonbehavioral risk associated with an increased risk for HIV, HBV and HCV performed by the US Public Health Service (the PHS Guideline) should be used to revise guidance for screening donors of human cells, tissues and cellular and tissue based products (HCT/Ps). Donors of organs and donors of tissues are sourced from the same US population and the information in the PHS Scott A Brubaker Page 23 8-25-2014 CHILD Uniform DRAI Stakeholder Review Group Discussion Document re: Juvenile Correctional Facilities & Donor Screening Guideline is the most up-to-date information available regarding risk for these three relevant communicable diseases. Collection of risk information should be the same but how the information is used to make donor eligibility determinations will differ. Final determination After much discussion, the (Child) DRAI Stakeholder Review Group voted in late August 2014 to use age 6 as the cut-off for the DRAI process’s inquiry regarding incarceration. The vote results were: prefer age 6 = nine prefer age 7 = eight no response = five abstained = four (agree with majority) Scott A Brubaker Page 24 8-25-2014