Effect of sediments on growth of duckweed

advertisement

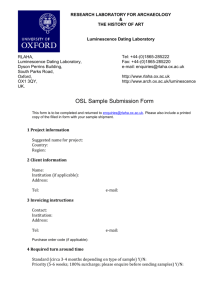

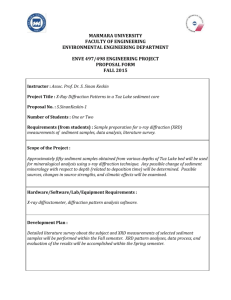

1 The effect of sediment exposure on Lemna minor population growth Harvey Rabbit Biology 203 Laboratory Section: Monday Submitted to: whoever 12 November 20xx 2 Abstract Duckweed, Lemna minor, is a small, aquatic plant frequently manipulated by ecologists due to its rapid growth rate. The purpose of this experiment was to observe the effects of the presence or absence of pond sediment on growth of Lemna minor. We grew duckweed under 430-W grow lamps slightly above room temperature for two weeks. We placed 25 thalli in each of five, 100-mL beakers containing a nutrient-rich medium without sediment. We repeated this process in another set of five beakers but added 10 mL of sediment to each beaker. Duckweed in the presence of sediment grew at a rate of 0.155 ± 0.0059 d-1, and in the absence of sediment grew at a rate of 0.131 ± 0.0082 d-1. After one week’s growth, blue-green algae formed in beakers containing sediment. Copper absorption by organic matter in the sediment probably caused the faster growth rate of duckweed and presence of algae. Subsequent studies would be required to explore whether sediment increases the L. minor growth rate regardless of copper contamination. Introduction A duckweed plant (Lemna minor) is a small, free-floating, aquatic plant. It is found on the surface of any still body of water with the proper nutrients for its growth. An example environment would be a swamp or pond. These plants are found across Eurasia and temperate North America. Ecologists use duckweed to measure population growth because of its easy maintenance and high asexual reproduction rate. Lemna minor have a simple structure. Each duckweed plant is called a thallus. The thallus is a miniature leaf floating on the water’s surface with a rootlet extending into the water below. Duckweed form clumps containing varying numbers of thalli. Through 3 reproduction, new thalli emerge around the border of parent plants and eventually break free. Sometimes they stay attached to the parent plant (Taylor, 2013). In our experiment, we observed the effects of pond sediment on the growth of Lemna minor. We extracted the pond sediment from the duckweed’s original habitat. Our previous experiment confirmed that duckweed grew sufficiently in a mixture of essential nutrients (Taylor, 2013). Unfortunately, it did not test the effects on the growth of L. minor in the absence and presence of sediment. One study proved that in the absence of sediment, teflubenzuron, an insecticide toxic to duckweed, slowed the growth rate of L. minor, but in the presence of sediment the growth rate was not inhibited (Medeiros et al., 2013). Therefore the pond sediment reduced the toxicity of teflubenzuron. This proved that sediment absorbs toxins, promoting duckweed growth. We did not know if the pond sediment would still have a positive effect on the growth of Lemna minor regardless of toxins, but we believed that chemicals absorbed or released by the sediment may help increase L. minor growth. We therefore hypothesized that the addition of sediment to each individual treatment beaker would increase the population growth rate of L. minor. Materials and Methods Lemna minor needs a specific set of environmental conditions to grow. A 430-W, high-pressure sodium lamp provided light for the duckweed. This lamp was designed for hydroponic agriculture, meaning that it produced wavelengths similar to the wavelengths emitted by sunlight. Altering the lamp’s height provided a light level of 400 mol. photons m-2s-1. The temperature was maintained at 24°C. We used 10 labeled 100-mL beakers to grow our duckweed. We labeled five of these beakers as our control beakers. Each control beaker contained 90 mL of duckweed 4 medium (Table 1). Duckweed medium mimicked pond water and provided all the dissolved nutrients in larger amounts to obtain healthy thalli. We placed 25 healthy thalli, removed from the large tank in the laboratory, into each of the control beakers filled with duckweed medium. The duckweed in the laboratory tank, as well as its sediment, were removed from an unnamed pond adjacent to Gaspereaux Lake in Antigonish County. We labeled the other five beakers as our sediment treatment beakers. Each sediment treatment beaker contained approximately 10 mL of sediment extracted from the bottom of the large tank. Following, we added duckweed medium until we reached the 90 mL mark on each one of the beakers. In each one of the beakers we placed a penny. The pennies contained trace amounts of copper which controlled the growth of cyanobacteria in the beakers. We placed all of the beakers in a mesh basket under the sodium lamp to begin growth (Taylor, 2013). Unfortunately the pennies did not subdue the growth of blue-green algae in the beakers containing the sediment treatment. On October 29, 2013, we did a 30-mL medium change in both the control and treatment beakers to remove some of the algal growth. This worked efficiently and the algae continued to grow but remained in manageable amounts for the duration of counting. We observed and counted our duckweed every day for two weeks within a few hours of 5:00 pm. Each day we removed the mesh container from under the light and counted each thallus with the aid of a paintbrush. During our counting we made observations about the general healthiness of the duckweed and the presence of algae. After we counted the thalli, we stirred each beaker with the end of the paintbrush to ensure proper nutrient distribution to the rootlets. 5 Table 1. Composition of duckweed medium. All of the ingredients below were added to distilled water. Chemical Name Formula Concentration (mg/L) Potassium Nitrate KNO3 350 Calcium Nitrate Ca(NO3) 4H2O 295 Potassium Phosphate KH2PO4 100 Magnesium Sulfate MgSO4 7H2O 100 Calcium Carbonate CaCO3 Ferric Chloride FeCl3 6H2O 0.76 Zinc Sulfate ZnSO4 7H2O 0.18 Manganous Chloride MnCl2 4H2O 0.18 Boric Acid H3BO3 0.12 Ammonium Molybdate (NH4)6Mo7O24 H2O 0.04 30 We replaced the mesh tray in a different area after each counting to alter its angle of light exposure. We also had to fill each beaker to the 90 mL mark with distilled water because of water loss through evaporation. This did not affect the concentration of the chemicals in the duckweed medium (Taylor, 2013). To analyze our data we plotted the mean number of thalli of both the control and treatment data sets against time in days. I then used Student’s t-test to compare numbers of thalli in control and treatment beakers. . Following, I did a regression analysis. I first plotted the Ln-transformed data to visualize an estimation of both growth rates. I then calculated the regression equations of the control and sediment treatment beakers on Excel. With these values, I used a special form of the t-test to compare the two slopes (rvalues) to see if the growth rates of the control and treatment populations were significantly different. 6 Results: our experiment went very well. We counted our duckweed every day and had a wide range of data to test. Our only issue was the algal growth in the beakers containing sediment. Algae began to grow after one week of counting. This algal growth, however, did not affect duckweed growth rate. The thalli continued to multiply and appeared to have both longer rootlets, and broader fronds. The mean number of thalli in the control beakers increased from 25 ± 0 to 155.2 ± 32.1 (SD) over 14 days. The mean number of thalli in the sediment treatment beaker had a larger increase from 25 ± 0 to 233.6 ± 80.5 (Figure 1). Both curves represented exponential growth, although the curve representing sediment treatment was more defined as exponential. This visually represented that the growth rate with sediment was more rapid, although we cannot conclude that the difference in the mean number of thalli between either population was significant over the two week counting period (t=1.14, P>0.05, df=28). The intrinsic growth rate, r, of the L. minor colony exposed to sediment was larger than the intrinsic growth rate of the control colony (Figure 2). The control group grew at rate of 0.131 ± 0.00815 d-1 and the group exposed to sediment grew at a rate of 0.155 ± 0.00594 d-1. there was a significant difference between the growth rates of the two populations (t=4.57, P<0.05, df=26). 7 Control High Density 350 Number of Thalli 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 0 2 4 6 8 Time (Days) 10 12 14 Figure 1. Effect of sediment exposure on growth of Lemna minor under a 430-W light for two weeks. The control was grown in only duckweed medium and the treatment was grown in medium exposed to sediment. Each point represents the mean of five replicates. Error bars are standard deviation. Discussion the intrinsic growth rate of the L. minor population when exposed to sediment was greater than the growth rate of the L. minor control population. The rootlets may have been longer in the sediment treatment colonies because the thalli had to compete for nutrients with the blue-green algae. By extending their rootlets they would have been able to absorb the nutrients in the duckweed medium that the blue-green algae couldn’t reach. The fronds in the sediment 8 Control Treatment 6 Ln (Number of Thalli) 5.5 5 4.5 4 3.5 3 0 2 4 6 8 Time (Days) 10 12 14 Figure 2. Ln-transformed data with best lines of fit representing estimations of the intrinsic growth rates of the control (r=0.131 ± 0.136) and the sediment treatment (r= 0.155 ± 0.0994) populations of Lemna minor. Each point represents the mean of five replications (P<0.05). treatment beakers may have been larger to create a larger surface area to absorb light from the grow lamps. Therefore these plants exhibited overgrowth competition to grow over the algae to reach the light first (Cain et al. 2011). Algal growth in the sediment beakers occurred because the organic matter in the sediment absorbed copper from solution. most copper ions in solution are strongly attracted and bind to organic matter, and as a result do not travel far after their release into the water (Sauvé et. al. 1997). According to one experiment on the sorption of copper by various organic sorbing agents, organic matter can absorb the metal from very 9 dilute, 2.5 to 4.5% copper solutions (Kashirtseva, 1960). Our beakers presumably contained very dilute concentrations of copper from the pennies, and therefore organic matter in sediment would have absorbed the metal from the medium. As we learned in preliminary experiments, , the copper in pennies can prevent algal growth in beakers. There was a 50% inhibition in carbon fixation, nitrogen fixation, and accumulation of chlorophyll a at 15-20 µg/L of added copper to blue-green algae samples (Wurtsbaugh & Horne, 1982). Therefore as copper is added the growth rate of blue-green algae decreases. Since the sediment in our beakers absorbed the copper, bluegreen algae grew rapidly. Also, Phosphorus released into the water by sediment is a major cause of excessive algae growth (“Nutrients: Phosphorus,” 2008). This could also explain the excess algae in our treatment beakers. The copper that was absorbed by the organic matter in the sediment may have affected the growth rate of the thalli. copper disrupts L. minor growth even in sub-lethal doses. In this experiment, the lowest duckweed growth rates of 0.03 were found in beakers containing copper and either Cr or Pb (Uçüncü et al., 2013). The containers containing only Cr and Pb had higher growth rates ranging from 0.05 to 0.10, and the control container had a growth rate of 0.06 (Uçüncü et al., 2013). Another experiment concluded that in copper concentrations of 1000 µg/L there was a 90% growth inhibition on L. minor (Megateli et al., 2009). Therefore as copper is added to solution L. minor growth rate falls, supporting our results. In the control beakers, copper in solution remained in the duckweed medium and the growth rate fell, while the sediment in the treatment beakers absorbed the copper from solution and the growth rate rose. 10 We do not know the exact chemical contents of the sediment used in our experiment, but it may have contained certain chemicals needed for optimal growth. We couldn’t prove this due to the copper contamination and sediment absorption that affected the growth rate. We are also uncertain of the exact quantity of organic matter in this particular pond sediment. In the future, the contents of the sediment should be analyzed prior to experimentation. Our study adds to our understanding of the importance of plant growth exposed to their original sediment and sediment’s removal of toxins in solution. A further study to test our hypothesis would be to test the growth of L. minor in the presence and absence of sediment without the addition of pennies. Although algae growth will persist, this would allow researchers to see if the growth rate was still faster when the duckweed were exposed to sediment, or if the removal of copper by the sediment was the sole variant on growth rate. Literature Cited Cain, M. L., Bowman, W. D., Hacker, S. D. (2011) Ecology (2nd ed.) (pp. 242-244). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Kashirtseva, M.F. (1960). Experimental data on sorption of copper by various minerals and organic sorbing agents. International Geology Review, 1(2). Medeiros, L. S., Souza, J. P., Winkaler, E. U., Carraschi, S. P., Cruz, C., Souza-Júnior, S. C., Machado-Neto, J. G. (2013). Acute toxicity and environmental risk of 11 teflubenzuron to Daphnia magna, Poecilia reticulata and Lemna minor in the absence and presence of sediment. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, 48(7), 600-606. Nutrients: Phosphorus, Nitrogen Sources, Impact on Water Quality, 3(22). 2008 Retrieved from http://www.pca.state.mn.us/index.php/viewdocument.html?gid=7939 on 1 November 2013 Sauvé, S., McBride, M. B., Norvell, W. A., Hendershot, W. H. (1997) Copper solubility and speciation of in situ contaminated soils: effects of copper level, pH and organic matter. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 100(1-2), 133-149. Taylor, B.R. 2013. Introductory ecology: Laboratory manual 2013. St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, NS, Canada Uçüncü, Esra E, Tunca, E., Fikirdeşici, Ş, Devrim, Ö, Altidağ, A. (2013). Phytoremediation of Cu, Cr and Pb Mixtures by Lemna Minor. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2013-11, 91(5), 600-604. Wurtsbaugh, W. A., Horne, A. J. (1982). Effects of copper on nitrogen fixation and growth of blue-green algae in natural plankton associations. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 39, 1636-1641.