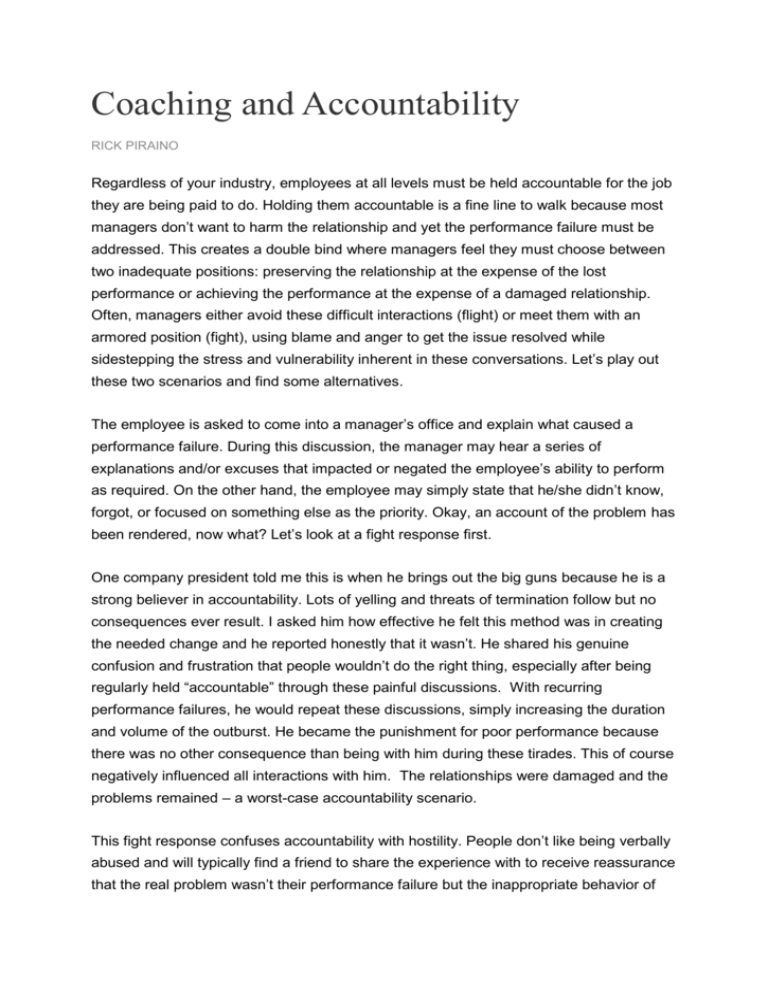

Coaching and Accountability

advertisement

Coaching and Accountability RICK PIRAINO Regardless of your industry, employees at all levels must be held accountable for the job they are being paid to do. Holding them accountable is a fine line to walk because most managers don’t want to harm the relationship and yet the performance failure must be addressed. This creates a double bind where managers feel they must choose between two inadequate positions: preserving the relationship at the expense of the lost performance or achieving the performance at the expense of a damaged relationship. Often, managers either avoid these difficult interactions (flight) or meet them with an armored position (fight), using blame and anger to get the issue resolved while sidestepping the stress and vulnerability inherent in these conversations. Let’s play out these two scenarios and find some alternatives. The employee is asked to come into a manager’s office and explain what caused a performance failure. During this discussion, the manager may hear a series of explanations and/or excuses that impacted or negated the employee’s ability to perform as required. On the other hand, the employee may simply state that he/she didn’t know, forgot, or focused on something else as the priority. Okay, an account of the problem has been rendered, now what? Let’s look at a fight response first. One company president told me this is when he brings out the big guns because he is a strong believer in accountability. Lots of yelling and threats of termination follow but no consequences ever result. I asked him how effective he felt this method was in creating the needed change and he reported honestly that it wasn’t. He shared his genuine confusion and frustration that people wouldn’t do the right thing, especially after being regularly held “accountable” through these painful discussions. With recurring performance failures, he would repeat these discussions, simply increasing the duration and volume of the outburst. He became the punishment for poor performance because there was no other consequence than being with him during these tirades. This of course negatively influenced all interactions with him. The relationships were damaged and the problems remained – a worst-case accountability scenario. This fight response confuses accountability with hostility. People don’t like being verbally abused and will typically find a friend to share the experience with to receive reassurance that the real problem wasn’t their performance failure but the inappropriate behavior of the boss. Like the mum who yells at and threatens her misbehaving kids in the grocery store but does nothing to stop their behavior, our boss is teaching his employees that there are no consequences for their “misbehavior” other than enduring his tirades and so it doesn’t matter if they “behave” or not. This threatens the emotional bank account and leadership credibility and, over time, will deplete them both. The more common response is flight. This happens at all levels and can take on many guises. For example, another boss asked me to coach her VP of Sales. He brought in lots of business but was inconsistent in getting complete and accurate information necessary to fulfill the sale and communicating it to others. After several sessions she asked if I thought he could be saved. I said yes but that he would need feedback on his performance and would need progressive discipline if he wandered from the action plan supporting his required changes. She rejected the idea that she should have to manage the performance of someone in a VP position and eventually fired a $4 million dollar producer for her company. Many managers have not been trained in the skills required to do this part of their job (surprisingly common) or they just may not think they should have to manage the work of another adult on the job. The result: inadequate performance doesn’t get addressed. What we permit persists. Small problems can grow in this scenario until the manager no longer cares about the relationship and then makes a first visit to HR expecting the employee to be terminated. No conversation, no feedback, no progressive discipline – just out. In both examples, there is little understanding of the function of accountability in shaping desired workplace behavior. Fair and impartial consequences must be delivered when necessary but these interactions should not progress into shouting matches that carry no consequences and hurt future loyalty, performance, and retention. Genuine accountability effectively shapes employee behaviors while maintaining positive relationships until performance requirements are successfully met – the only resolution to the manager’s double bind. This means that at no time should the relationship ever be used as the punishment for performance failures. It is this relationship that the Gallup research in First, Break All The Rules, tells us is the single most important variable in creating a strong and successful workplace. We cannot afford to lose it to reactivity, hostility, and blame; rather, it is the best tool we have to create excellence with our employees. Elements Of Accountability Discussions: 1. Just the facts ma’am. Clear your descriptions of the problem of any judgments, criticism, or assumptions. Simply describe the problem behavior – what the employee did or said – without embellishment. 2. Investigate. Make sure you understand the root cause of the problem. By demonstrating genuine curiosity, you will ensure your full understanding of the problem and the employee’s goodwill as you build a resolution that can solve the problem once and for all. 3. Play your part. Remember, we owe our employees a set-up for success. If they don’t have what they need to succeed, they can’t give us the behaviors we want. Ensure that the expectations are clear, and that the necessary training, resources, and feedback have been provided. If we don’t provide these elements, we can’t ethically hold people accountable for their lack of performance. 4. Be consistent, fair, and dispassionate when delivering established consequences. Don’t underline the seriousness of the consequence with emotional reactivity that moves the focus of their attention from their performance failure to your upset. This will make it easier for them to discount their behavior and emphasise your misbehavior with them. Keep the attention on their performance. 5. Finally, address the problem early, when it is still small and easier to resolve. Remember, it’s easy to justify avoiding at this stage – naturally; choosing your battles and the timing of the interaction is important considerations. But the danger in waiting is that it will allow the problem to become more serious, creating the potential for greater harm for the company, the employee, and often the manager who did not address it early on. Some early accountability in the form of feedback can help save all three from more serious consequences.