Management of the Giant Northern Termite DOCX

advertisement

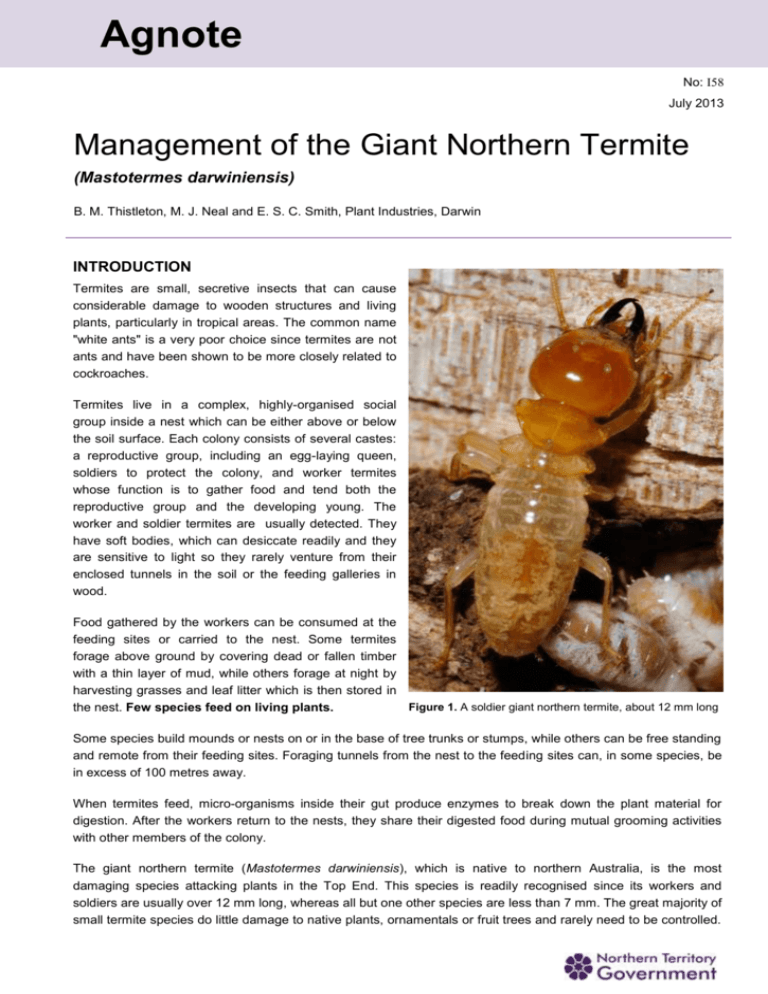

Agnote No: I58 July 2013 Management of the Giant Northern Termite (Mastotermes darwiniensis) B. M. Thistleton, M. J. Neal and E. S. C. Smith, Plant Industries, Darwin INTRODUCTION Termites are small, secretive insects that can cause considerable damage to wooden structures and living plants, particularly in tropical areas. The common name "white ants" is a very poor choice since termites are not ants and have been shown to be more closely related to cockroaches. Termites live in a complex, highly-organised social group inside a nest which can be either above or below the soil surface. Each colony consists of several castes: a reproductive group, including an egg-laying queen, soldiers to protect the colony, and worker termites whose function is to gather food and tend both the reproductive group and the developing young. The worker and soldier termites are usually detected. They have soft bodies, which can desiccate readily and they are sensitive to light so they rarely venture from their enclosed tunnels in the soil or the feeding galleries in wood. Food gathered by the workers can be consumed at the feeding sites or carried to the nest. Some termites forage above ground by covering dead or fallen timber with a thin layer of mud, while others forage at night by harvesting grasses and leaf litter which is then stored in Figure 1. A soldier giant northern termite, about 12 mm long the nest. Few species feed on living plants. Some species build mounds or nests on or in the base of tree trunks or stumps, while others can be free standing and remote from their feeding sites. Foraging tunnels from the nest to the feeding sites can, in some species, be in excess of 100 metres away. When termites feed, micro-organisms inside their gut produce enzymes to break down the plant material for digestion. After the workers return to the nests, they share their digested food during mutual grooming activities with other members of the colony. The giant northern termite (Mastotermes darwiniensis), which is native to northern Australia, is the most damaging species attacking plants in the Top End. This species is readily recognised since its workers and soldiers are usually over 12 mm long, whereas all but one other species are less than 7 mm. The great majority of small termite species do little damage to native plants, ornamentals or fruit trees and rarely need to be controlled. Some species can attack timber in service (houses, sheds, pergolas, decking etc.). In these situations it is recommended that you contact a Pest Control Officer. The remainder of this Agnote deals only with the giant northern termite and its control in trees but not in timber in service. BIOLOGY OF THE GIANT NORTHERN TERMITE Eggs (Figure 2) are laid in small batches and hatch into immatures (Figure 3). These can either develop into workers and soldiers (Figure 4) or into nymphs (Figure 5) which produce winged adults called alates. Figure 2. Giant northern termite eggs Figure 3. Giant northern termite immatures Figure 4. Giant northern termite workers, soldiers and eggs Figure 5. A giant northern termite nymph Alates (Figure 6) disperse, lose their wings and become primary kings and queens. However, the establishment of new colonies by this method is uncommon. The workers can moult into wingless secondary reproductives, called neotenics (Figure 7), and they are the main egg-laying caste in giant northern termite colonies. Colonies increase in size by producing neotenics and budding off from the main colony. This is an important consideration for control since a termite-free area is at the greatest risk of colonisation underground along its borders with existing colonies. © Northern Territory Government Page 2 of 7 Figure 6. A giant northern termite winged adult Figure 7. Giant northern termite secondary reproductives (neotenics) In native bush, colonies of the giant northern termite are small in extent and numbers of individuals, and most of the hollow trees are caused by Coptotermes spp., not Mastotermes. However, in areas developed for horticultural and forestry use, colonies can be huge, covering several hectares underground and consisting of large numbers of individuals. These colonies often have many nests with secondary reproductives and nurseries of immature termites, such as the one shown under an old mango tree (Figure 8). It has been demonstrated that nests are connected by underground tunnels and that the termites move freely between them. Figure 8. A giant northern termite nest under an old mango tree SYMPTOMS OF GIANT NORTHERN TERMITE ATTACK Trees infested with termites often show no external signs of their presence nor are adverse effects always caused. The most common early symptoms of infestation are yellowing, wilting and drying of leaves, and the death of shoot tips or whole branches on an otherwise healthy-looking tree. As the infestation progresses, symptoms include occasional bursts of new growth that then wilt and die, branches that fold over (Figure 9) and mud-covered galleries on the outside of the trunk. Worker termites enter the tree through the root system or through the base of the tree below the ground. They then move up through the heartwood and start to hollow out the upper branches weakening the structure of the © Northern Territory Government Page 3 of 7 tree. Sometimes they will move to the outside of the tree and run several deep grooves (Figure 13) around the trunk which they cover with mud. This is referred to as ringbarking and, together with extreme internal damage (Figures 10 and 11), can cause the death of the tree (Figures 12 and 14). Foraging galleries radiating from the nest can be in excess of 100 metres and are usually found within 20 cm of the soil surface although they have been recorded at depths of several metres following tree roots or sourcing water. . Figure 9. "Folded” cashew branches Figure 10. Damage to a Caribbean pine Figure 11. Exposed galleries in a cut mango trunk Figure 12. A mango tree killed by giant northern termites Figure 13. Ring barking on a cypress Figure 14. An African mahogany killed by giant northern termites © Northern Territory Government Page 4 of 7 PLANTS ATTACKED The great majority of common native trees, including (in order of preference) acacias, grevilleas, eucalypts and terminalias are attacked. Most introduced plants are also susceptible. The more commonly attacked trees are mango, cashew, citrus, poinciana, gmelina, aralia, African mahogany, and many palm species. MONITORING FOR TERMITES Termites can be monitored by looking for the symptoms described and illustrated above. However, external signs are often only evident when the internal damage is already extensive. Trunks of larger trees, such as mature mango, can be drilled into the centre using a 13-mm bit to locate the central galleries (Figure 15). If termites are active in the tree, they will seal the hole with mud within 24 hours. This process can be carried out on groups of trees in areas where termite infestation is suspected Where monitoring is required along borders between uninfested and infested blocks, rows of sacrificial plants, such as cassava, grevilleas or acacias can be planted or wooden billets placed in the ground. These should be monitored for damage every two to three months and, if infestations are found, the termites should be aggregated (see below) and controlled. Figure 15. Drilling a cashew tree to detect a giant northern termite infestation TERMITE CONTROL Termiticides Since worker termites radiate from the central nest to forage for food, the application of fast-acting insecticides to the feeding sites will kill them at that site but few others will be affected. However, if a slow-acting insecticide is used, the workers will carry it back to the nest and, by transferring it to other members during grooming and feeding, the colony can be greatly reduced. The recommended termiticide with such properties is fipronil (Termidor® or Regent®). Its use in horticultural crops is covered by a number of Minor Use Permits issued by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA). These permits give detailed directions on how to apply the termiticide for a variety of situations. These methods include soil injection, trunk injection and application to aggregation drums. Since these © Northern Territory Government Page 5 of 7 permits change over time, they are not listed here, but current ones can be downloaded from the APVMA website (http://www.apvma.gov.au) or can be obtained by contacting DPIF. Soil and trunk injection The Minor Use Permits allow fipronil to be applied to some species of infested trees by injecting into the soil around the roots or directly into the trunk through the holes drilled for monitoring purposes. Since fipronil is carried to adjacent trees up to 25 m away and sometimes farther, it is often not necessary to treat all trees in infested groups. Where it is possible, the trunk injection method is preferable as the chemical runs down inside the trunk and directly into underground galleries in the roots or the soil. Termites in these galleries do not contact the insecticide so readily when it is injected into the soil. Details of tree species, concentrations and amounts of chemical to use are given on the Minor Use Permits. Aggregation drums To maximise the transfer of the chemical to the colony, it is advantageous to apply it to as many termites as possible. Often when the infestations are in small trees, the number of termites in each tree is relatively small. In such a situation, it is far better to aggregate the termites into aggregation drums (Figures 16 and 17). Figures 16 and 17. Aggregation drums This method involves locating active galleries in trees, under mulch, or under timber or old logs and placing drums from 20 L to 200 L in size with 12 to 15 finger-sized holes in their bases. The drums are filled with untreated timber (e.g. from old pallets or packing crates, not hardwood) or forest mulch, which is moistened and covered with a plastic bag and a lid. After four to six weeks the drums should be highly active with termites and can be treated by pouring the diluted chemical into the drum. The lid should be left off at this stage as the treated termites will move away from the light and back towards the nest. This technique is described in more detail in a poster and a booklet which can be downloaded from: Poster – www.nt.gov.au/d/Content/File/p/Plant_Pest/Termites_booklet.pdf Booklet – www.nt.gov.au/d/Content/File/p/Plant_Pest/Termites_poster.pdf It is important to allow an adequate time (four to six weeks) for the drums to become highly active. While there will be termites present long before this, treating too early will reduce the amount of chemical taken back to the colony. © Northern Territory Government Page 6 of 7 Management of colonies before planting horticultural crops It is advisable to control giant northern termites in native vegetation prior to and during clearing of the potential orchard area. If this is not done, the expense and difficulties of subsequent management in the fruit trees may be much greater than that of the initial control. Moreover, the investment in nurturing trees for several years to bearing stage may be wasted. Monitoring can include checking for dead or dying trees, ringbarking or muddying on the outside of larger trees, dying or folded branches on grevilleas or acacias and other smaller trees, and under fallen timber. Larger trees can also be drilled and checked after 24 hours for muddying as described above. In large areas, it is often useful to set up a grid of about 50-m spacing and monitor each of the lines. When drilling the trees, re-walk the grid after 24 hours and check for mud in the holes. A muddied hole indicates termite activity. Push a metal rod or wooden stick into the hole to clear out the mud, then insert a grass stem or a very fine stick into the hole and move it vigorously, then leave it for a few seconds. If the tree is infested, the soldiers will grip the grass with their mandibles and can be extracted. The majority of the muddied holes will be caused not by giant northern termites but by Coptotermes spp. These are easily recognised as they are much smaller. Only the giant northern termites need to be treated as most Coptotermes mounds will be destroyed during the clearing process. The active sites should be marked with a GPS, tape or paint ready for treatment by trunk injection. During clearing, infested trees can also often be detected since the trunk or larger branches break apart more readily than those of un-attacked trees and the damage can be easily inspected in felled timber. Active sites should be marked and treated. Please visit us at our website: www.nt.gov.au/d © Northern Territory Government ISSN 0157-8243 Serial No. 734 Agdex No. 622 Disclaimer: While all care has been taken to ensure that information contained in this document is true and correct at the time of publication, the Northern Territory of Australia gives no warranty or assurance, and makes no representation as to the accuracy of any information or advice contained in this publication, or that it is suitable for your intended use. No serious, business or investment decisions should be made in reliance on this information without obtaining independent and/or professional advice in relation to your particular situation. © Northern Territory Government Page 7 of 7