Psychology and Law, Now and in the Next Century

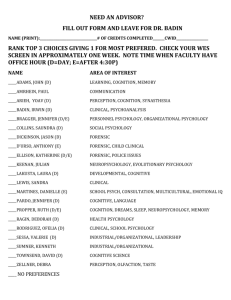

advertisement