The Influence of Management Accounting Artefacts on Micro

advertisement

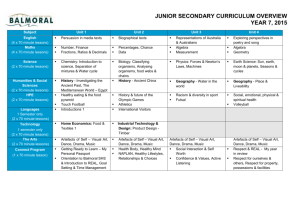

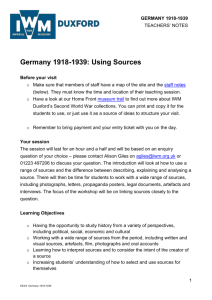

The Influence of Management Accounting Artefacts on Micro-Processes in Practice: A Conceptual Framework and Case Analysis b Sharlene Biswasa*, Chris Akroyd & Norio Sawabe a Department of Accounting and Finance The University of Auckland Business School Private Bag 92019 Auckland, New Zealand Email: s.biswas@auckland.ac.nz Phone: +64 9 923 5356 b College of Business Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon, USA Email: chris.akroyd@bus.oregonstate.edu c Graduate School of Management Kyoto University Kyoto, Japan Email: sawabe@econ.kyoto-u.ac.jp c *Corresponding author 1 The influence of management accounting artefacts on micro-processes in practice: A conceptual framework and case analysis ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to examine why management accounting (MA) artefacts may or may not influence micro-process level practices. In particular, we focus on the influence that MA artefacts have on the practice of different groups of organizational actors in an innovation setting. We start by developing a conceptual framework for the analysis of the micro-processes, which make up organizational practices. The framework is built on three key principles. Firstly, it treats MA artefacts and organizational practices as separate distinct concepts. Secondly, it takes into account the power differences among actors and thirdly, it recognizes the existence of different perspectives that actors have within an organization. The framework draws attention to the actions of organizational actors and their ability to change MA artefacts. We then use a case study to show why the everyday practices of actors may differ from those prescribed by the MA artefacts. The case study findings show that the influence of MA artefacts on innovation practice was dependent on the perspectives of the top managers and project managers involved in the innovation setting. We show that when the perspectives of the top managers were aligned with the perspectives of the project managers, the everyday innovation practices encoded the MA artefacts. However, when their perspectives were different, practices became decoupled from those prescribed by MA artefacts. Keywords: Institutional practices, decoupling, inter-organizational innovation, management accounting artefacts, actor perspectives. 2 1. INTRODUCTION The management accounting literature has increasingly recognized the need to understand how practices develop and how change is accomplished (Burns and Scapens, 2000; Englund and Gerdin, 2013; Seo and Creed, 2002). Past research has devoted a considerable amount of effort to understanding the processes of institutionalization and why management accounting (MA) artefacts change (Burns and Scapens, 2000; Dambrin et al., 2007; Quinn, 2014; Sharma et al., 2010). In comparison, there are relatively few studies, which examine the role of MA artefacts1 in relation to how the practices of organizational actors change. This highlights an assumption in much of the management accounting literature that changes in MA artefacts have a linear relationship with change in the practices of organizational actors. However, studies highlighting the decoupling phenomenon (Lukka, 2007; Nor-Aziah and Scapens, 2007; Quinn, 2014) suggest that changes to MA artefacts may have little or no impact on actors’ organizational practices (Ancelin-Bourguignon et al., 2013; Lounsbury, 2008). This literature suggests that there is a need for additional studies focused on institutions and the micro-processes of organizational actors in practice (Ancelin-Bourguignon et al., 2013; Lounsbury, 2008; Smets and Jarzabkowski, 2013). According to Lounsbury (2008, p. 351), “This gap between actor micro-processes and institutions provides an important opportunity for theoretical development and empirical insight, and the new directions of institutional analysis being developed can help to open up this multi-level, meso range of research.” Accordingly, we believe that examining the gap between an organization’s MA artefacts and organizational actor micro-processes can help us understand the dynamics of change and stability in specific organizational settings. Thus, the purpose of this study is to examine why MA artefacts may or may not influence changes in the micro-process level practices of organizational actors. We start by developing a conceptual framework for analysis of micro-processes, which draws attention to the actions of organizational actors with varying levels of power to change MA artefacts and their everyday practices in the organization. We then use a case study to show how the MA artefacts influence the micro-processes of everyday practices through an analysis of the actions of organizational actors. We do this by examining a particular organizational 1 In this study, the MA artefacts we focus on are the formalized control procedures used by management to facilitate the attainment of their goals and those of the organization (Kober et al., 2007). 3 practice, the inter-organizational innovation practice, and seek to understand the reasons for the actions of organizational actors in this context. The structure of the remainder of this paper is as follows: Section 2 discusses the interorganizational innovation literature and presents our conceptual framework. Section 3 presents the research methodology and provides an overview of the case organization. Then in section 4, using the conceptual framework, we explain why different organizational perspectives resulted in decoupling between the actions of organizational actors and the MA artefacts. Moreover, we discuss the role that MA artefacts play in facilitating the decoupling process. In section 5, we discuss the findings in relation to the literature. Finally, section 6 concludes the paper with some limitations and suggestions for future research. 2. LITERATURE REVIEW & CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK Lounsbury (2008, 2007) suggests that conceptualizing organizational environments as multiple and fragmented can generate new insights about change and practice variation. Hence, this paper focuses on one function at our case organization, the innovation function and in particular, the inter-organizational collaborative practices of innovation teams. The choice of the innovation function was motivated by the literature on the change in innovation thinking from a closed (internal) process to a more open (external and collaborative) approach (Chesbrough, 2006, 2003; Chiaroni et al., 2011; Enkel et al., 2009; Gassmann et al., 2010; van de Vrande et al., 2009). This literature highlights the significant differences in firms’ adoption and implementation of these practices without much attention given to the reasons for these variations. Hence, this paper may also contribute to the innovation literature by providing some insights on the cause of practice variation. Innovation is different to most other business processes where managements’ focus is on efficiency. Innovation, on the other hand, requires flexibility to foster creativity and the exploration of new opportunities (Jørgensen and Messner, 2009). Organizational actors need to be able to change routines and try new things in order to develop new products and processes. Hence, like many early researchers have found, MA artefacts could be a hindrance to innovation (Dougherty and Hardy, 1996; Gerwin and Kolodny, 1992; Leonard-Barton, 1995). However, because resources are scarce, companies require investments in new products to align with their strategies and be executed efficiently. Therefore, it is important for firms to get 4 the right balance between flexibility and efficiency. In this context, MA artefacts may help rather than hinder a firm’s innovation efforts (Adler et al., 1999; Jørgensen and Messner, 2009). Past management accounting research has demonstrated how the combination of different control mechanisms can help an organization balance efficiency and flexibility (Jørgensen and Messner, 2009), and how MA artefacts can play different roles at different stages of the innovation process (Akroyd and Maguire, 2011; Davila, 2000; Davila et al., 2009). For example, MA artefacts help reduce uncertainty (Akroyd and Maguire, 2011; Davila, 2000) but can also increase goal congruence (Akroyd and Maguire, 2011). Studies have also found that MA artefacts are useful tools to support organizational transformations (Chenhall and Euske, 2007; Dambrin et al., 2007; Ezzamel et al., 2004). However, relatively little research attention has been given to studying the influence of MA artefacts in relation to change and stability of a firm’s innovation practices. Consequently, this study examines why MA artefacts may or may not influence the inter-organizational innovation practices at the case organization using the principles of the conceptual framework discussed below. 2.1. Conceptual Framework In the management accounting literature, the concept of institutional logic has been used to account for the micro-processes of change in practice and practice variations. AncelinBourguignon et al. (2013, p. 207) argue that “institutional logic refers to sets of unquestioned norms, assumptions and beliefs existing at the macro-social levels. They determine the values, identities and self-representation of individuals in a social group and define the form of rationality and cognitive processes in that group”. Empirical evidence from Lounsbury (2007) shows how distinct logics lead to different forms of understanding, which in turn generate distinct practices. Inês et al. (2009) also find that multiple logics can co-exist within an organization informing the consciousness of the organizational actors and leading to practice variations. These studies imply that institutional logics shape people’s perspectives, which influence their actions. However, to evaluate the outcome of actions, it is important to take into consideration the concept of power. As argued by Hardy (1996, p.9), “change does not occur in a vacuum - it takes place in a system in which a certain distribution of power is already entrenched.” Baum (1989) suggests power is the ability of different groups of individuals to achieve something they could not accomplish individually. Hardy (1996) suggests there are four dimensions of mobilizing power: power over resources, power over decision making, power over meaning 5 and power over the system. Burns (2000) examined these in an innovation setting and found that while the first three dimensions can together be used to facilitate change, the fourth dimension, power over the system, can act as a significant barrier to change. Burns (2000) suggests that the power over the system refers to the existing institutional context, which is reinforced by the organizational actor’s background, education, training and work experience. The paper showed how the mobilization of power over resources, decision making and meaning, led to the development of MA artefacts. However, these failed to affect the actions of the innovation teams because of their own dominant institutions and routines. These findings indicate that there are at least two dominant groups of organizational actors in an organization’s innovation setting. One group has the power over resources, decision-making, and meaning. This group can use their power to introduce or alter MA artefacts. In contrast, the second group does not share this power but by having power over their system they can shape their microprocess level practices. Applying this to the innovation context, we argue that the output of the first group of actors’ (top managers) actions would be the MA artefacts relating to the innovation activities, while the output of the second group of actors’ (project managers) actions would be the organizational innovation practices. However, the institutional logic literature discussed above would suggest that the perspectives of the respective groups would influence their actions. Thus, if the perspectives of the two groups were different, we would expect to see innovation practices that are distinct and decoupled from the MA artefacts. In other words, the MA artefacts may have no influence over the innovation practices. On the hand, we would expect the innovation practices to mirror the actions prescribed by MA artefacts when the perspectives of the project managers are aligned with the perspectives of the top management. In this case, changes to MA artefacts may have an influence on the innovation practices. Based on the above literature review we propose that the MA artefacts are enactments of the top management’s perspectives while the organizational practices are enactments and reproductions of the perspectives of the project managers (see Figure 1). This paper conceptualizes that the MA artefacts may be encoded into the practices of organization actors. However, practices can also exist that are decoupled from the MA artefacts. Therefore, we believe that it is important to study the MA artefacts and the practices of organizational actors separately. 6 Figure 1: Conceptual framework for micro-level analysis We propose that by studying the practices of top managers and project managers, we can understand their perspectives and thus explain some of the reasons for the gap between an organization’s MA artefacts and organizational actor’s micro-processes. This may help us understand some of the dynamics of stability and change influencing MA artefacts and organizational practices. We apply this conceptual framework to a case study in the following sections. 3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY & CASE ORGANIZATION A case study approach was selected for this study to show why MA artefacts may or may not influence the micro-processes of change in practice within an organization. This requires the study of the MA artefacts along with the people that design, use and influence the MA artefacts through their everyday practice. Hence, a case study was deemed to be an appropriate method as it involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon (Adams et al., 2006; Yin, 2009) offering the opportunity to analyze suggestive themes and counterpoints, interpretations and 7 counter-interpretations as well as the analysis of different views around practices in an organization (Ahrens and Dent, 1998). The case site we study, NZMed (a pseudonym) as described below, was selected through purposeful sampling to enable us to address the above research question and to examine our proposed conceptual framework. As explained by Patton (1990, p.169), “the logic and power of purposeful sampling lies in selecting information-rich cases for study in depth. Informationrich cases are those from which one can learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the research.” 3.1. Description of Case Organization NZMed is a leading designer, manufacturer, and marketer of a range of innovative healthcare devices. At the time this research took place, NZMed’s products were sold in over 120 countries worldwide through direct sales operations in most major markets along with a network of distributors that sell to hospitals, home healthcare providers, distributors, and other manufacturers of medical devices. NZMed is largely based in New Zealand where its headquarters, R&D, as well as manufacturing facilities are located. However, it also has sales and marketing operations located in 30 countries around the world to support its customers. The company had a growth strategy as explained by one of the top managers2: “The Company’s consistent growth strategy is to provide an expanding range of innovative medical devices which can help to improve care and outcomes for patients in an increasing range of applications.” NZMed’s innovation function was deemed to be one of the key pillars in its growth strategy and investment in research and development (R&D) was believed to be fundamental as expressed in the following quote by one of the top managers: “New and improved products and processes, along with the development of new medical applications for our technologies, are critical drivers of our annual revenue and earnings growth. We remain committed to expanding our R&D activities”. 2 In this case, top management consisted of the senior executives in the organization who were responsible for allocating resources and making the strategic decisions including the implementation of MA artefacts. Project managers on the other hand consisted of organizational actors that were directly involved in the day-to-day innovation activities within the firm. 8 Engineers, from the CEO who had an electronic engineering background, to the new graduates joining the innovation teams, dominated NZMed. Hence, the culture in the firm and the mindset of the people in the firm were complementary to the firm’s innovative approach. Moreover, as shown in Figure 2, an integral part of NZMed’s R&D model was seeking ideas for new products or improvements to existing products along with seeking advice and feedback on conceptual designs or quality of products from end-users and medical professionals. Similarly, project teams frequently collaborated with local suppliers or potential suppliers to develop or improve new product components. However, these collaborations were restricted to small specific development problems as the project teams felt restricted in what they could share with this group of external partners. On the other hand, collaborations with larger research organizations like universities and crown research institutes3 were rare. Figure 2: Shape of NZMed's open innovation practices 3 Crown research institutes are Crown-owned companies that carry out scientific research for the benefit of New Zealand 9 3.2. Data Collection and Analysis Empirical data for this study was collected using semi-structured interviews along with an analysis of archival documents. The interviews included organizational actors who were considered to be most involved and have inside knowledge of the innovation practices of the firm. Interviewees included organizational actors from different hierarchical levels. They were chosen in order to understand their actions and get the viewpoints of people with different levels of ability to change the MA artefacts and innovation practices in the firm. Interviews included a mixture of in-depth one-to-one interviews as well as some group discussions, which were conducted over 18 months from October 2009 to March 2011. A good cross section of organizational actors ranging from company executives to the employees directly involved in the everyday activities of innovation projects were interviewed. Number of People interviewed Total Hours of Interview Data Number of Documents 17 15 36 Table 1: Summary of interview hours, number of people interviewed and documents reviewed We started by interviewing project managers who were directly involved in managing the dayto-day innovation activities. The initial interviews involved the participants talking about their daily activities. They explained in detail about the actions they took to complete an innovation project from start to finish including the interactions they had with external parties. The interviewees were asked to explain the reasons for the specific actions they described. The interviewees frequently used examples of recent projects they were involved with to explain their points. However, due to confidentiality reasons, we have not included these project specific examples in this paper. The relevant MA artefacts were identified from the initial interviews with the project managers. These MA artefacts were then discussed in interviews with the top managers along with discussions around what their role was, their daily activities, their involvement with the innovation activities of the organization and their perspectives in relation to interorganizational practices. The final interview stage involved group discussions with the project managers to get an understanding of the consistency of their actions and perspectives. In line with an interpretative research methodology (Chua, 1986; Ryan et al., 2002; Willmott, 2008), the intent of the interviews was to get an understanding of the organizational actors’ perspectives and account of the micro-processes of change in the organization’s innovation 10 practices. Hence, priority was given to interviewees’ own interpretations and perceptions of the change or stability they experienced or believed existed. Other than the introductory meetings, all the interviews were recorded and transcribed. However, the introductory meetings as well as all follow-up phone conversations were documented and analyzed in the same way as the transcribed interviews. The interview data was also corroborated through analysis of company documents. A large range of documents and presentation slides relating to innovation projects were reviewed and analyzed along with information provided on the company’s website. Firstly, these were used to develop an understanding of the company and its activities. Secondly, they were used to corroborate the interview data such as the existence of the MA artefacts and innovation practices encoding these MA artefacts. Nvivo was used to help analyze the data using a thematic approach that grouped data into themes that emerged from the interviews. The interviews were first analyzed individually and then compared within the groups and across the two groups to identify similarities and differences between them. The findings are discussed below. 4. FINDINGS The aim of this section is to report the findings of our case study. We begin by explaining how two of NZMed’s MA artefacts i.e. the value statement and the intellectual property (IP) rules influenced the inter-organizational innovation practices at NZMed. We then examine a gap between NZMed’s IP rules and the actor micro-processes in relation to collaborations with suppliers. We demonstrate how different perspectives led to the creation of the gap and explain the role that MA artefacts played in shaping the different perspectives. Finally, we summarize the finding and reflect on how the conceptual framework helps explain why MA artefacts may or may not influence a firm’s micro-process level practices. 4.1. The influence of MA artefacts An analysis of the interview data combined with the results of the document review showed that the value statement was one of the key MA artefacts at NZMed that influenced the shape of its inter-organizational activities. This MA artefact was seen as a belief system put in place to guide the behavior of organizational actors. It did not tell the organizational actors what to do but it highlighted the values that the organizational actors needed to exhibit in their day-today activities. The value statement was frequently mentioned during formal meetings, was 11 displayed in the company’s reception area, and was on the company website as well as in their annual reports. As explained by one of the interviewees, the purpose of this value statement was to communicate and reinforce top management’s belief that it was beneficial and important to interact with end-users and medical professionals to understand their needs. The top management’s view was summarized in the following quote: “Top management at NZMed insist that the engineers involved in R&D be out there interacting with the users and potential users of their products. They insist that engineers go out into the hospitals, understand what is happening, try to understand the market and come up with new ideas.” The interviewee explained that the reasoning behind this was that by being out in the field, the engineers were able to think practically, identify potential issues that may arise, get a feel for what will work and what will not. Top managers explained that project teams needed to understand the current and future needs of end-users in order to fulfil the company’s vision to develop devices that could improve patient care and increase NZMed’s growth opportunities. This was seen as a core value for the firm and hence in their opinion needed to be emphasized and reinforced in a formalized manner. The project managers on the other hand explained that the existence of a value statement that highlighted the importance of understanding the current and future needs of patients had resulted in the organizational actors at all hierarchical levels recognizing the need for project teams to build a strong relationship with hospitals. This recognition was depicted in the regular visits to the hospitals by project teams where they interacted with patients and medical professionals to enhance their learning and product improvements. The project managers shared the top management’s perspectives in relation to the interactions with end-users and medical professionals, which, translated into the existence of an inter-organizational innovation practice in NZMed and encoded its value statement (see Figure 3). Moreover, as explained by different project managers, healthy collaborations at the consumer end of the value chain had given project teams the confidence to seek input from external parties at the supply end of the value chain as well. The view among the project managers was that by seeking input from external parties they were learning and increasing their knowledge. 12 Figure 3: Result of consistent perspectives of top management and project managers However, while top management at NZMed encouraged the project teams to interact with endusers and medical professionals, they insisted on maintaining other MA artefacts that strongly encouraged in-house innovation activities. Interviews with NZMed’s top management revealed that they were confident that NZMed would have a steady flow of relevant project ideas coming to them from their highly skilled employees and people interested in working with NZMed. Hence, there was no need to invest large amounts of resources in searching for these opportunities. However, while NZMed had been successful in attracting some good opportunities, collaborations with research organizations such as universities and Crown research institutes were rare, which the project managers attributed to the top management’s views on IP ownership as epitomized by this quote from a member of the top management team: “For us there is a fairly narrow range of situations where we see the ability for collaborative innovation and that tends to come down to an intellectual property issue. That is, whether we can ring fence the IP and make sure that we do not open ourselves to a situation where there is a dispute about who owns the IP”. 13 As the top management interviewees explained, they were not against the idea of collaborations with the external parties but the primary rule for the project teams was to establish the ownership of IP upfront. One of the interviewees from the top management team explained the reasons behind top management’s hard line on IP as follows: “There are a couple of reasons for NZMed’s hard line on IP. Firstly, if you start putting royalties on a product, that compromises your margin and you end up in a situation where if you take a product for argument sake and it had a 10% margin on it and you used three pieces of someone else’s IP. If they all asked for 2% royalty then all of a sudden your margin has gone to 4% and it is not looking viable anymore. And you cannot ever get out of that situation. You know you are stuck forever in that situation where you are paying out that royalty. So, that is one issue. The other issue is just around the management of who owns what parts of that IP. So, if you imagine for example that you are working with a research institute be it a university, etc., and you do not have an agreement that one party will own all the IP. Then you end up in a situation where there is uncertainty as to what the cost of that IP will be later on for us as a company. And there is also the issue about whether we will own it at all and whether that IP might be also licensed to one of our competitors for example. So, I can only think of a couple of very rare exceptions where we have not insisted on owning the IP. That would be our default position to insist on that before we began even preliminary discussions”. These top management views on IP were enacted as the formalized rules around confidentiality and IP ownership. The top management interviewees explained the purpose of the rules were to set limits on what organizational actors could do to protect the firm from the risks of valuable information leaking to competitors and the risk of committing to business arrangements that could compromise the quality of NZMed’s products and reduce profit margins. In other words, the purpose of the rules was to eliminate external partners that did not share NZMed’s interests. However, the discussions with project managers suggested that there was a difference between the organizational actors’ practices in relation to seeking external input from suppliers during the innovation process, and the expected action as per these formalized rules around IP. In other words, the practice of collaborating on innovation projects with local suppliers was decoupled from the formalized rules on IP. The rules on IP required collaborations to be based on contractual agreements determined through a negotiation process carried out prior to any 14 project discussions with external parties. However, the project managers tended to bypass the process of negotiating contractual agreements with local suppliers and instead attempted to build long-term associations based on trust and mutual understanding. The following subsection discusses how the different perspectives led to the creation of decoupled practices. 4.2. Decoupling and different perspectives One of the interviewees summarized the project managers’ view on external collaborations with local suppliers as: “We are not looking so much for what I would describe as a transactional-based approach. We are looking for a more relationship-based approach. So for example, we would or I would prefer and I think this represents the company’s view to a large extent, we would prefer to have an arrangement where we are working together with an external party, without tying ourselves down to very specific project goals, milestones, etc. because to be innovative as a company you need to be prepared to follow things as they develop. If you think of a project, it might be three to five years to develop something. If you sit down at the beginning and define exactly what all the steps are going to be, exactly what the milestones are going to be, etc., then you do not have much flexibility to follow those opportunities that may arise as you go along. And if you think of the whole concept behind innovation, it is all about being able to follow those things when they come up and knowing which things to follow.” As explained by the project managers, collaborations with local suppliers worked because they were able to by-pass the process of holding upfront discussions about IP ownership. The project managers were confident that IP ownership was not an issue in most of these cases. The project managers believed that one of the advantages of external collaborations was that external parties with expertise could drive the collaborations, bringing in pre-existing knowledge rather than NZMed project teams trying to learn everything from the beginning. Therefore, things that external parties were able to figure out in a couple of days would probably have taken a lot longer if attempted in-house. Consequently, the project managers explained that when they believed they did not have the expertise in-house and required help from external parties, they first determined what they 15 needed help with. As explained by the project managers, during the conceptual design stage4 they identified specific items they needed to develop for their projects, for example, extrusions, different types of tubing, or clips. Then they went with a very specific requirement to someone they thought had the expertise to help them develop it, rather than just having a broad conversation about some of the ideas they were thinking about doing. As NZMed project managers tended to approach vendors that had the expertise to deal with the specific problem, the solutions provided by these suppliers were usually incremental innovations of the suppliers’ processes, for which obtaining patents was not necessary. Obtaining patents for these small local suppliers was costly and defending them would have been close to impossible. Hence, for these suppliers the cost of IP ownership outweighed the benefits removing the conflict of interest over IP ownership and hence reducing the perceived risks of not owning an IP as highlighted by the top management. Figure 4: Result of different perspectives of top management and project managers 4 This stage is where the project teams take the business cases and define the product in more depth spelling out desired product features, attributes, requirements and specifications. These are translated into designs for the product, which are then executed into prototypes. These initial prototypes are then evaluated usually with the help of potential users such as medical professionals. 16 Therefore, as depicted in Figure 4, the perspectives of the project managers were not aligned with the perspectives of the top management described in the previous sub-section. The two groups acted according to their own perspectives, which translated to the existence of organizational practices and MA artefacts, which were not aligned with each other A further analysis of the perspectives of the two groups suggested that there were a number of macro-social level factors influencing their perspectives. For instance, the top management suggested their perspectives were influenced by the government and industry regulations, past experiences of the top managers and institutional pressures such as legitimacy. On the other hand, the project managers indicated that their perspectives were influenced by their past experiences, their external networks and the location of NZMed. However, most importantly we found that the company’s MA artefacts influenced the perspectives of the two groups. The following sub-section discusses the influence of these MA artefacts on the perspectives of the two groups and how the MA artefacts facilitated the decoupling process. 4.3. Influence of MA artefacts on organizational actors’ perspectives An analysis of the interview data from NZMed showed that the MA artefacts did not coerce the innovation practices of the project managers but instead the project managers chose to use them where they believed it was appropriate. At the same time, they by-passed the MA artefacts repairing the innovation practices where they believed the MA artefacts were hindering their activities. It can be seen from the interview data that the perspectives of the project managers were based on an operational view where the focus was on getting a new product to the market quickly and within a reasonable cost. This focus can be linked to the operational goals for the project teams which talks about how many patients are treated using their products in a given period of time. This goal equates to the number of products that the division and the company sells. As explained by one of the project managers, one of the ways to increase market share is by offering new products that cater to different market segments. For example, one of their core products when launched was only available in a size that fitted adults. However, it was soon realized that there was a large market for a similar product for children/small adults and babies. While on the surface, it appears as if you just need to reduce the size of the product, but developing smaller units had its own challenges. This triggered other innovation projects that had to take place before the new variations of the product could be launched in the market. However, all innovation projects were evaluated based on its Return on Investment (ROI) that 17 takes into consideration the cost of the innovation project including the labor hours spent on the project by the engineers. As explained by one of the project managers, this is one of the most significant costs of R&D and the longer a project lasts, the higher this cost would be. In other words, ROI would be lower and the project might be stopped at the first hurdle as any project at NZMed with an ROI of less than 100% was rejected. Therefore, it was in the interest of project teams to reduce the time to market and related costs to ensure the new products could be launched in the market so that the division could achieve their goals. This is where the collaborations with local suppliers that help speed up the development process makes sense as opposed to the lengthy process they need to engage in when dealing with larger research institutes. In other words, the short-term operational goals were instrumental in influencing the project managers’ perspective. They tailored the everyday innovation practices based on their views of how they can best achieve the desired outcome of launching new products in the market within the shortest timeframe based on the resources and the opportunities that are available weighed against their assessment of the risk that the opportunities pose. In contrast, the perspectives of the top management were based on the long-term strategic view where the focus was on profit margins and long term growth targets while ensuring compliance with regulatory and industry requirements. As explained by one of the top management interviewees, “we need to be thinking in five to ten year timeframes”. The MA artefacts implemented by top management for the management of NZMed’s innovation function e.g. the value statement and the rules around IP ownership reflected the top management’s way of thinking. In other words, the empirical evidence suggests that the perspectives of the top management influence their actions, which were inscripted as MA artefacts put in place to promote congruence with organizational strategies. However, as shown in this case, the influence of these MA artefacts on the organization’s practices was dependent on how the organizational actors interpreted them. Sometimes the interpretations of the organizational actors differed from the intentions of the top management making the MA artefacts appear not to be aligned with other MA artefacts in the organization. For example, it appeared that the operational goals set for the project teams were not aligned with the rules around IP ownership. We find that this was because the project managers interpreted the operational goals with a short-term view while the top management took a longterm view when designing and implementing the relevant MA artefacts. This was because the 18 interpretations of the existing MA artefacts are inter-twined with the perspectives of the two groups, which are then reflected in their actions. 4.4. Discussion of Findings This case study showed that the influence of MA artefacts on the inter-organizational innovation practices of NZMed was dependent on the perspectives of the project managers including their interpretation of the MA artefact. The study found that where the perspectives of the top management were aligned with the perspectives of the project management, the everyday innovation practices of the project teams encoded the MA artefacts. However, where the top management’s perspectives and the project managers’ perspectives were different, the project managers adapted their innovation practices to achieve what they believed was the best operational outcome. In other words, the difference in perspectives of the two dominant groups of organizational actors in NZMed, led to repair efforts by project managers. We find that this repair effort was enabled by the project managers’ power over their system, which was reinforced by their experiences, their external networks and more importantly by their understanding of their operational goals. This power allowed the project managers to act according to their perspectives and not be coerced by the MA artefacts into acting according to the top management perspectives. However, the project managers’ lack of power over decisionmaking and ability to change MA artefacts meant the project managers repair efforts created a gap between the MA artefacts and the organizational innovation practices. Therefore, it was essential to treat MA artefacts and organizational practices as separate distinct concepts. In one instance the organizational practices encoded MA artefacts (i.e. MA artefacts influenced actor micro-processes regarding visits to hospitals) while in another instance organizational practices were decoupled from the MA artefacts (i.e. MA artefacts did not influence actor microprocesses regarding IP negotiations). In summary, the case study adds support to the proposed framework by demonstrating that to understand why MA artefacts may or may not influence a firm’s micro-processes, it is essential to do the following: firstly, separate MA artefacts from organizational practices. Secondly, recognize the difference in power and separate the group with the power to influence and change MA artefacts from the group with the power to influence the shape of organizational practices through repair efforts. Thirdly, recognize the existence of different perspectives across the groups as this will influence their actions and the use of their power. 19 5. DISCUSSION In addition to applying the principles of the proposed framework, this case study has enabled us to contribute to the management accounting literature in a number of ways. Firstly, this study showed how MA artefacts influence inter-organizational innovation practices. The role of MA artefacts in the innovation context has always been a controversial topic with some studies supporting the view that MA artefacts help innovation efforts (Akroyd and Maguire, 2011; Davila, 2000) while others argue that MA artefacts hinder innovation efforts (Dougherty and Hardy, 1996; Gerwin and Kolodny, 1992). This paper shows that MA artefacts can help organizations shape their innovation practices. However, this is dependent on the perspectives of the organizational actors with the ability to change organizational practices. If they agree with the actions prescribed by the MA artefacts, then their actions will encode the MA artefacts. Alternatively, the MA artefacts will be by-passed to create decoupled practices. The decoupling phenomenon is not new to the management accounting literature as studies have found that organization’s MA artefacts are not always coupled with the organizational routines (Lukka, 2007; Nor-Aziah and Scapens, 2007; Quinn, 2014). However, existing institutional frameworks (e.g. Burns and Scapens, 2000; Sharma et al., 2010) have been criticized for not clearly distinguishing between MA artefacts which they conceptualize as part of the organization’s rules (how things should be done) and routines (how things are actually done). It has been argued that the relation between them could be better examined by separating them (Lukka, 2007; Nor-Aziah and Scapens, 2007; Quinn, 2011; Sawabe and Ushio, 2009). Another issue faced by the researchers when trying to use existing institutional frameworks relates to the ambiguity surrounding the definition of routines (Burns and Scapens, 2000; Quinn, 2014, 2011). Burns and Scapens (2000) suggests that routines are not action per se and are largely tacit which makes them difficult to observe and compare. Hence, the proposed framework may offer an alternative for researchers examining the influence of MA artefacts or the decoupling phenomenon as the framework is built on the following three principles: 5.1. Treating MA artefacts and organizational practices as separable concepts Firstly, we draw on Lounsbury (2008) and the institutional logic literature (AncelinBourguignon et al., 2013; Inês et al., 2009; Lounsbury, 2007) which proposes the study of actors and practices. As the purpose of the proposed framework is the analysis of the micro20 process level of practice, we propose that researchers examine the actions of organizational actors involved in that practice. Here we define actions as what people do during their everyday activities to fulfil their responsibilities. For example, at NZMed the act of project team members visiting hospitals to interact with medical professionals was seen as an action. Reproductions of these actions by the same organizational actors and other organizational actors in similar roles would constitute the organizational practices. Apart from the criticisms in the literature regarding the conceptualization of routines, we argue that the use of actions instead of routines as the unit of analysis is better because the people who are doing the activities can easily describe actions. Moreover, in organizations like NZMed, actions relating to functions like innovation are documented to keep track of what activities were performed, in case they need to replicate the activities or an audit is performed for quality purposes. Hence, researchers can utilize a number of data collection methods including interviews, document analysis and observations to identify the actions that constitute the practices. These can then be compared with the MA artefacts. 5.2. Recognizing power differences Secondly, the proposed framework takes into account the differences in organizational actors’ power over resources, decision-making, meaning and system (Burns, 2000; Hardy, 1996). Differences over these powers constitutes to a difference in the ability to change MA artefacts and organizational practices (Burns, 2000). Hence, we argue that decoupling exists because of this difference in the organizational actor’s ability to change the MA artefacts and the organizational practices. For example, the project managers at NZMed were able to shape innovation practices through their actions. They could bypass the actions prescribed by the MA artefacts where they deemed necessary but they could not change the MA artefacts, as this needed the sanctioning of the top management. We acknowledge that the project managers can influence the decisions of top management to change the MA artefacts. In this case, the perspectives of the top management would change and subsequently be reflected in the new MA artefacts. We also acknowledge that each individual may have different beliefs and views. The project managers may disagree with each other’s views but we assume that the actions that constitute the organizational practices are representative of the common and dominating view among that group. Similarly, the members of the top management group may have distinctive views and ideas but for them to be reinforced as MA artefacts there needs to be consensus among them. For instance, the CEO needs to get the other top managers to agree on any changes to the MA artefacts before they can be actioned. Hence, in the conceptual framework, we 21 narrow it down to only two types of perspectives, which refer to the common and dominant views among the two groups: one with the ability to change MA artefacts and one with the ability to change organizational practices. 5.3. Recognizing the existence of different perspectives Separating the MA artefacts from the practices of project teams enables the study to focus on the gap between the MA artefacts and the organizational practices. This helps recognize the existence of different perspectives within the organization and the impact these different perspectives may have on the micro-process level of practices within the organization. This principle is aligned with the institutional logic literature that provides evidence of the coexistence of multiple logics within an organization informing the consciousness of the organizational actors and leading to practice variations (Inês et al., 2009; Lounsbury, 2008). The literature on institutional logic suggests that the consciousness of organizational actors is influenced by unquestioned norms, assumptions and beliefs existing at the macro-social level (Ancelin-Bourguignon et al., 2013; Lounsbury, 2008). However, in this study we show that the organization’s MA artefacts and organizational actors’ interpretations of the MA artefacts also influence the perspectives of the organizational actors. Therefore, we propose that future research could look into incorporating the micro-process level factors such as an organization’s MA artefacts into the concept of institutional logic. 6. CONCLUDING REMARKS This paper shows that MA artefacts may or may not influence a firm’s micro-process level practices by separating MA artefacts from organizational practices, recognizing differences in power and the existence of different organizational perspectives. The paper develops a conceptual framework based on these three principles and applies it using a case study of NZMed. The case study shows how MA artefacts influence the perspectives and actions of organizational actors that shape the firm’s micro-process level practices, in this case within an inter-organizational innovation setting. Moreover, the paper shows how the practices of organizational actors with different perspectives can create decoupled practices and the role that MA artefacts play in facilitating the decoupling process. We recognize the limitations of a case study methodology regarding the generalizability of the results (Yin, 2009). However, the evidence from this case study helps us demonstrate the principles of the conceptual framework proposed in the paper which can be examined in other 22 contexts in future studies. Another limitation of this study is that it takes a static view and is reliant on interview data and the analysis of archival documents. Future research could use observational data collection methods, which could provide additional insights into processes of change, changes in perspectives, changes in MA artefacts and organizational practices as well as the causal effects of change. Nevertheless, the framework proposed in this paper provides new insights and can be used to analyze the influence of MA artefacts on a firm’s micro-process level practices in different contexts. For example, it could also be used to analyze change in other business settings such as explaining how firms’ can shift to become more sustainable. However, we recognize that the proposed framework is an early stage compilation of ideas based on the innovation context and we welcome future studies to revise and improve it making it applicable for use in other contexts. REFERENCES Adams, C., Hoque, Z., McNicholas, P., 2006. Case studies and action research, in: Hoque, Z. (Ed.), Methodological Issues in Accounting Research: Theories and Methods. Spiramus Press Ltd, London, pp. 361–373. Adler, P.S., Goldoftas, B., Levine, D.I., 1999. Flexibility versus efficiency? A case study of model changeovers in the Toyota production system. Organ. Sci. 10, 43–68. Ahrens, T., Dent, J.F., 1998. Accounting and organizations: Realizing the richness of field research. J. Manag. Account. Res. 10, 1–39. Akroyd, C., Maguire, W., 2011. The roles of management control in a product development setting. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 8, 212–237. Ancelin-Bourguignon, A., Saulpic, O., Zarlowski, P., 2013. Subjectivities and microprocesses of change in accounting practices: a case study. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 9, 206–236. Baum, H.S., 1989. Organizational Politics Against Organizational Culture: A Psychoanalytic Perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. 28, 191. Burns, J., 2000. The dynamics of accounting change: Inter-play between new practices, routines, institutions, power and politics. Accounting, Audit. Account. J. 13, 566. Burns, J., Scapens, R.W., 2000. Conceptualizing management accounting change: an institutional framework. Manag. Account. Res. 11, 3–25. 23 Chenhall, R.H., Euske, K.J., 2007. The role of management control systems in planned organizational change: An analysis of two organizations. Accounting, Organ. Soc. 32, 601–637. Chesbrough, H., 2003. Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts. Chesbrough, H., 2006. Open innovation: A new paradigm for understanding industrial innovation, in: Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J. (Eds.), Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 1–12. Chiaroni, D., Chiesa, V., Frattini, F., 2011. The Open Innovation Journey: How firms dynamically implement the emerging innovation management paradigm. Technovation 31, 34–43. Chua, W.F., 1986. Radical Developments in Accounting Thought. Account. Rev. 61, 601– 632. Dambrin, C., Lambert, C., Sponem, S., 2007. Control and change - Analysing the process of institutionalisation. Manag. Account. Res. 18, 172–208. Davila, A., 2000. An empirical study on the drivers of management control systems’ design in new product development. Accounting, Organ. Soc. 25, 383–409. Davila, A., Foster, G., Li, M., 2009. Reasons for management control systems adoption: Insights from product development systems choice by early-stage entrepreneurial companies. Accounting, Organ. Soc. 34, 322–347. Dougherty, D., Hardy, C., 1996. Sustained product-innovation in large, mature organizations: overcoming innovation-to-organization problems. Acad. Manag. J. 39, 1120–1153. Englund, H., Gerdin, J., 2013. Call for Papers for Management Control Association. Manag. Account. Res. 24, II–III. Enkel, E., Gassmann, O., Chesbrough, H., 2009. Open R&D and open innovation: exploring the phenomenon. R&D Manag. 39, 311–316. Ezzamel, M., Lilley, S., Willmott, H., 2004. Accounting representation and the road to commercial salvation. Accounting, Organ. Soc. 29, 783–813. Gassmann, O., Enkel, E., Chesbrough, H., 2010. The future of open innovation. R&D Manag. 40, 213–221. Gerwin, D., Kolodny, H., 1992. Management of advanced manufacturing technology: strategy, organization and innovation. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester. Hardy, C., 1996. Understanding Power: Bringing about Strategic Change. Br. J. Manag. 7. 24 Inês, C., Maria, M., Robert, W.S., 2009. Institutionalization and practice variation in the management control of a global/local setting. Accounting, Audit. Account. J. 22, 91– 117. Jørgensen, B., Messner, M., 2009. Management Control in New Product Development: The Dynamics of Managing Flexibility and Efficiency. J. Manag. Account. Res. 21, 99–124. Kober, R., Ng, J., Paul, B.J., 2007. The interrelationship between management control mechanisms and strategy. Manag. Account. Res. 18, 425–452. Leonard-Barton, D., 1995. Wellsprings of knowledge. Harvard Business School Press, Boston. Lounsbury, M., 2007. A tale of two cities: Competing logics and practice variation in the professionalizing of mutual funds. Acad. Manag. J. 50, 289–307. Lounsbury, M., 2008. Institutional rationality and practice variation: New directions in the institutional analysis of practice. Accounting, Organ. Soc. 33, 349–361. Lukka, K., 2007. Management accounting change and stability: Loosely coupled rules and routines in action. Manag. Account. Res. 18, 76–101. Nor-Aziah, A.K., Scapens, R.W., 2007. Corporatisation and accounting change: The role of accounting and accountants in a Malaysian public utility. Manag. Account. Res. 18, 209–247. Patton, M.Q., 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed. Sage, Newbury Park, California. Quinn, M., 2011. Routines in management accounting research: further exploration. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 7, 337–357. Quinn, M., 2014. Stability and change in management accounting over time—A century or so of evidence from Guinness. Manag. Account. Res. 25, 76–92. Ryan, B., Scapens, R.W., Theobald, M., 2002. Research method and methodology in finance and accounting. Thomson, London. Sawabe, N., Ushio, S., 2009. Studying The Dialectics between and within Management Credo and Management Accounting. Kyoto Econ. Rev. 78, 127–156. Seo, M.-G., Creed, W.E.D., 2002. Institutional contradictions, praxis and institutional change: A dialectical perspective Acad. Manag. Rev. 27, 222–247. Sharma, U., Lawrence, S., Lowe, A., 2010. Institutional contradiction and management control innovation: A field study of total quality management practices in a privatized telecommunication company. Manag. Account. Res. 21, 251–264. Smets, M., Jarzabkowski, P., 2013. Reconstructing institutional complexity in practice: A relational model of institutional work and complexity. Hum. Relations 66, 1279–1309. 25 Van de Vrande, V., de Jong, J.P.J., Vanhaverbeke, W., de Rochemont, M., 2009. Open innovation in SMEs: Trends, motives and management challenges. Technovation 29, 423–439. Willmott, H., 2008. Listening, interpreting, commending: A commentary on the future of interpretive accounting research. Crit. Perspect. Account. 19, 920–925. Yin, R.K., 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. 26