Diphthongs. Processes of connected speech. R – coloring

advertisement

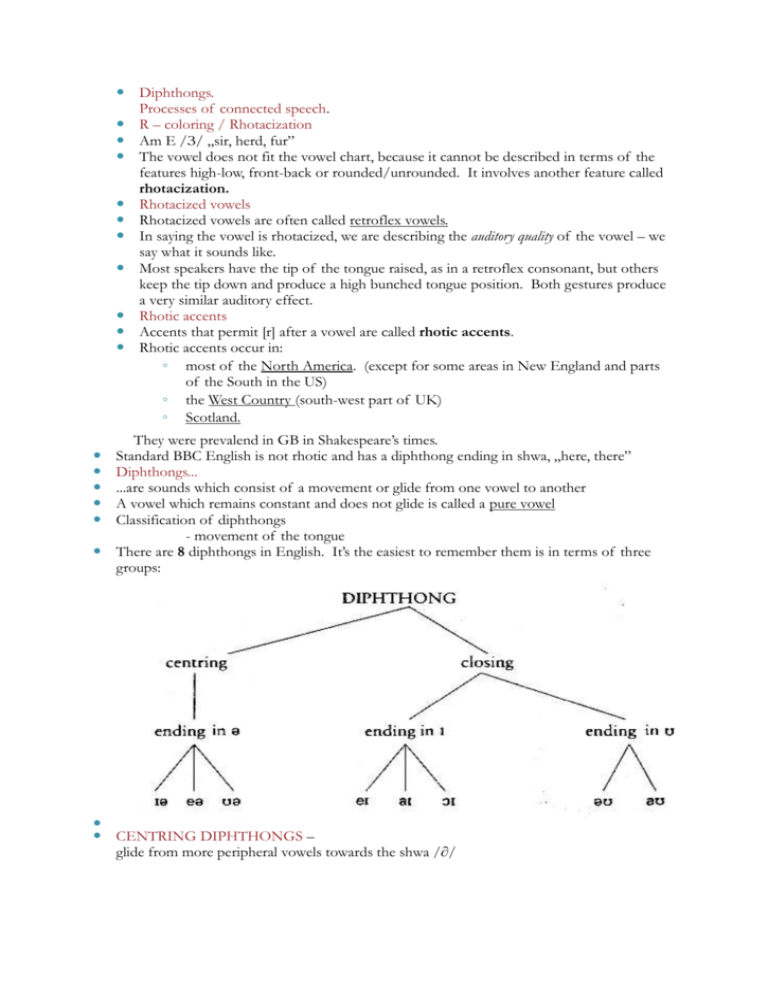

Diphthongs. Processes of connected speech. R – coloring / Rhotacization Am E /З/ „sir, herd, fur” The vowel does not fit the vowel chart, because it cannot be described in terms of the features high-low, front-back or rounded/unrounded. It involves another feature called rhotacization. Rhotacized vowels Rhotacized vowels are often called retroflex vowels. In saying the vowel is rhotacized, we are describing the auditory quality of the vowel – we say what it sounds like. Most speakers have the tip of the tongue raised, as in a retroflex consonant, but others keep the tip down and produce a high bunched tongue position. Both gestures produce a very similar auditory effect. Rhotic accents Accents that permit [r] after a vowel are called rhotic accents. Rhotic accents occur in: ◦ most of the North America. (except for some areas in New England and parts of the South in the US) ◦ the West Country (south-west part of UK) ◦ Scotland. They were prevalend in GB in Shakespeare’s times. Standard BBC English is not rhotic and has a diphthong ending in shwa, „here, there” Diphthongs... ...are sounds which consist of a movement or glide from one vowel to another A vowel which remains constant and does not glide is called a pure vowel Classification of diphthongs - movement of the tongue There are 8 diphthongs in English. It’s the easiest to remember them is in terms of three groups: CENTRING DIPHTHONGS – glide from more peripheral vowels towards the shwa /∂/ CLOSING DIPHTHONGS glide from /∂/ towards a closer vowel e.g. /I/ CLOSING DIPHTHONGS – gliding from /∂/ towards /υ – as in „good”/ Classification of diphthongs – prominence of the vowel In the 8 diphthongs above the most prominent part is the first vowel. The second vowel is very brief and transitory; sometimes it’s even difficult to determine its exact quality, e.g. /eI/ - a glide towards /I/ [ju] as in „cue – the most prominent vowel is the second one – many books in phonetics don’t consider it as a diphthong, but as a sequence of /j+u/ ◦ „pew, beauty, cue, spew, skew, also (BrE): tune, dune, Sue, Zeus, new, lieu, stew” – a lot of consonant clusters occur only before /u/; there is no /pje, kje/ etc. (Ladefoged 77) TRIPHTHONG - a glide from one vowel to another and to the third - five closing diphthongs + shwa ASSIMILATION ...is one of fast / connected speech processes Sounds belonging to one word can cause changes to sounds belonging to another word Assuming we know how a phoneme is produced in isolation, when we find the phoneme realized differently as a result of being near some other phoneme belonging to a neighboring word, we call this an instance of assimilation. Assimilation varies in extent according to speaking rate and style; it’s more likely to occur in rapid, casual speech than in slow, careful speech. Sometimes the difference is barely noticable, sometimes it’s big. ASSIMILATION ... affects mostly consonants; _ _ _ _ Cf | Ci _ _ _ _ _ If Cf changes to become like Ci in some way, the assimilation is called regressive/progressive (direction of influence) If Ci changes to become like Cf in some way, the assimilation is called regressive/progressive In what ways can a consonant change? Differences in place of articulation Differences in manner of articulation Differences in voicing In parallel with this, we distinguish: ◦ Assimilation of place ◦ Assimilation of manner, ◦ Assimilation of voicing Assimilation of place alveolar Cf followed by non-alveolar Ci e.g. /t/ becomes /p/ before a bilabial consonant „that person” /ðæt pЗ:s∂n/ „light blue” /ðæp pЗ:s∂n/ /laIt blu:/ „meat pie” /laIp blu:/ /mi:t paI/ /mi:p paI/ ? regressive or progressive? Assimilation of place Alveolar /t/ will change into dental /t/ before a dental consonant ◦ „that thing” / ðæt Өiŋ/ ◦ „cut through” /kΛt Өru:/ Alveolar /t/ will change into velar /k/ before a velar consonant ◦ „that case” / ðæk keIs/ ◦ „bright colour” /braIk kΛl∂/ In similar contexts /d/ /b,d, g/, and /n/ /m, n, ŋ/ but fricative alveolars behave differently: ◦ Assimilation of place Alveolar fricatives become palato-alveolar fricatives before palatal sounds /j, ∫/ /s/ /∫/ ◦ „this shoe” /ðI ∫ ∫u:/ /z/ /”ż” as in Gigi/ ◦ „those years” /ðoυż jI∂z/ ◦ ? Regressive or progressive ? The consonants that undergo assimilation do not dissappear Assimilation of manner much less noticable, only found in the most rapid speech a tendency for regressive assimilation the change is usually for the „easier” consonant – one which makes less obstruction to the air flow Assimilation of manner A plosive, a fricative or nasal ◦ „that side” / ðæs saId/ ◦ „good night” /gυn naIt/ ◦ ?regressive or progressive? A word-initial /ð/ follows a plosive or nasal at the end of the preceding word, it becomes identical in manner to the Cf, but with dental place of articulation ◦ „in the” /In n∂/ ◦ „get them” /get tem/ ◦ „read these” /ri:d di:z/ ◦ ? regressive or progressive? ◦ Assimilation of voice Only regressive assimilation is found across word boundaries If Cf is lenis („voiced”) and Ci is fortis („voiceless”), the lenis consonant has no voicing, e.g. „please stop” /z? s/ (It is not very noticable, as initial or final voiced consonants have little or no voicing anyway. ) When Cf is fortis (voiceless) and Ci lenis (voiced) assimilation of voice NEVER takes place, e.g. „that black dog” (/k/ doesn’t change to /g/) Across-morpheme and within-morpheme assimilation Across morpheme: progressive assimilation of voice for –s suffixes ◦ „cats” /kæts/; „dogs” /dogz/ Within the morpheme: a place of articulation of a nasal is determined by the place of articulation of the following consonant, e.g. „ bump, tenth, bank, hunt” /bΛmp, tenӨ, bæŋk, hΛnt/ - it’s become a fixed phonological rule ELISION ... under certain circumstances sounds disappear; a phoneme may „be realized as zero”, or „have zero realization”, or be deleted. Elision is typical of rapid, casual speech Gradation – a process of change in phoneme realizations by changing the speed and casualness of speech ELISION - examples Loss of a weak (unstressed) vowel after /p,t,k/ - aspiration takes up the whole of the middle of the syllable, e.g. „potato, tomato, perhaps, today” (transcription?) Loss of a weak vowel followed by n, l, or r, which becomes syllabic, e.g. „tonight, police, correct” ◦ Avoidance of complex consonant clusters, e.g. :George the Sixth’s throne” In clusters of three plosives or two plosives + fricative, the middle plosive disappears, e.g. acts /æks/, scripts /skrIps/ Loss of final „v” in „of ”/∂v/ before consonants, e.g. „lots of /∂/ them” „waste of /∂/ money” Contractions of grammatical forms (often not regarded as elision, as realized in spelling) e.g.: „would:” he’d /d/; Tom’d /∂d/ „is”: she’s /z/; duck’s /s/ „will”: she’ll /l/; duck’ll /l/ (! also after Cs) „have”: we’ve /v/; Tom’ve /∂v/ „are”: (∂ after vowels, ∂r after consonants + changes in preceding vowel): you’re /jυ∂/, those are /ð∂υz ∂r/ LINKING AND INSERTION linking „r” – the phoneme /r/ cannot occur in syllable-final position in RP, but when spelling suggests a final /r/ and a word beginning with a vowel follows, speakers usually pronounce /r/, e.g. : ◦ „here” /hI∂/ but „here are” /hI∂r ∂/ ◦ „four” /fo: / but „four eggs /fo:r egz/ intrusive /r/ without the spelling justification: ◦ „formula A” /fo; mj∂l∂r eI/ ◦ „media event” /mi:dI∂r ivent/ Bibliography: 1. Peter Ladefoged: A course in phonetics 2. Peter Roach: English phonetics and phonology (both in our library)