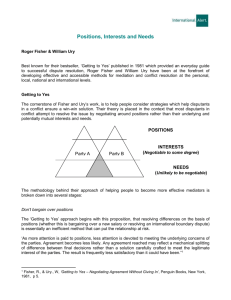

Getting to Yes

advertisement

Title: Getting to Yes Author: Roger Fisher and William Ury Year Published: 1981, second edition 1991 Reviewer: Yana Valachovic, University of California Date of Review: January 2012 Getting to Yes is focused on developing techniques to help negotiate agreements. This timeless book first published in 1981 reminds the readers about how hard it can be to find mutually agreeable solutions to conflicts and presents a set of strategies to overcome conflicts. The authors present four principles of negotiation: 1) separate the people from the problem; 2) focus on interests rather than positions; 3) generate a variety of options before settling on an agreement; and 4) insist that the agreement be based on objective criteria. The first principle of separating people from the problem helps to avoid personal attacks. If the negotiator can help the conflicted parties understand the other party’s viewpoint it can help bring to light differing interpretations of a situation. As a part of this principle it is also important to acknowledge that emotions run high when people feel threatened, so if the negotiator can lend a hand in recognizing the emotional state of the parties, these signals of empathy can help defuse the emotions. Furthermore it is essential that active listening be developed so that the conflicted parties are not just restating their positions without listening and learning of the other party’s issues. The second principle of focusing on interests rather than positions will help develop solutions that are mutually agreeable. If the negotiator can help the parties understand what are the key issues that motivate a person’s position and not just a restatement of viewpoints, then they authors state that it is much easier to help both parties begin to formulate possible solutions to the conflict. Fisher and Ury suggest that the sooner the conflicted parties can begin to actively work together to brainstorm possible solutions, by looking forward and not backward, the more likely it will be that they can negotiate a lasting solution. The third principle of generating a range of options is suggested so that solutions are not found prematurely. The authors recommend developing a robust brainstorming process where participants might use their “circle chart” to identify the problem, analyze the problem, the generate broad ideas on how to solve the problem, followed by developing specific actions that might be taken to solve the problem. Then only after a range of options should participants analyze the suggested solutions. Fisher and Ury suggest that participants should try to generate solutions that they believe the other side could agree to. The forth principle involves the development and use of objective criteria to evaluate proposed solutions to the conflict. The development of the criteria should be done together by both parties, this way the conflicted parties have an equal hand in the analysis and will have more buy-in to the process. The latter chapters in Getting to Yes are focused on extreme negotiations where the groups may not play by the rules or where one party may have significantly more power in the negotiations. They offer a range of ideas that focus on reinforcing the ideas mentioned above by emulating the standards for discussion, such as focusing on interests and not positions, along with mutually developing ground rules for the negotiation (so as to start the group buy-in to the negotiated process early on). Overall, for those that are looking to enhance their skills at working with groups that struggle with complex interests and inherent conflicts, this book is well worth the read.

![7-01 Conflicts of Interest [September 28, 2012]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007047489_1-d2a6690e7450d8e8b5531933a5aaee46-300x300.png)