Minimizing Anesthesia Emergence Delirium in

advertisement

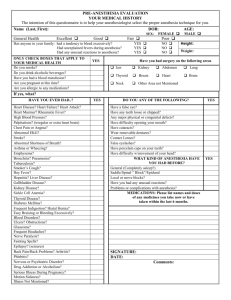

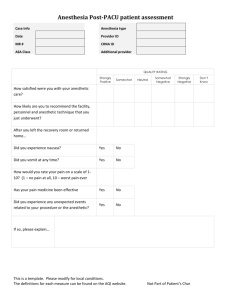

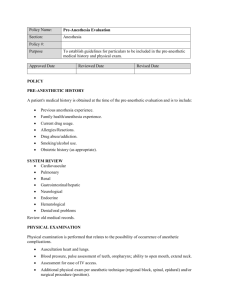

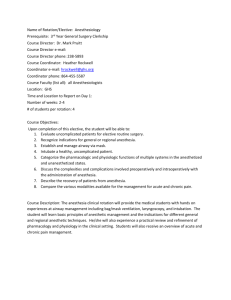

Minimizing Anesthesia Emergence Delirium in Combat Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Point of Contact: LTC Denise Beaumont, CRNA Chief of Anesthesia Services Bayne-Jones Army Community Hospital, Fort Polk, LA (337) 531-3340; Denise.M.Beaumont.mil@mail.mil Groups Involved with the Project: Anesthesia Department Operating Room Post-Anesthesia Care Unit Behavioral Health Department Bayne-Jones Army Community Hospital, Fort Polk, LA Submitted By: Donald J. Stafford, CRNA Army-Baylor University Healthcare Administration Resident, 2013-2014 Bayne-Jones Army Community Hospital, Fort Polk, LA 13 May 2014 Executive Summary: Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms experienced by combat veterans emerging from anesthesia may expose patient and staff to multiple risks. In addition, perioperative administrative and operational efficiencies can be adversely affected. An innovative, simple, no-cost protocol developed at Bayne-Jones Army Community Hospital appears highly successful at minimizing these issues through astute identification of susceptible patients, patient education, staff preparation, precise timing of specific anesthesia medications, controlling environmental stimuli, and applying the theory of consistency to staff assignments. While further research is needed to formally validate the preliminary findings, this protocol provides significant improvements in overall satisfaction, safety, risk mitigation, quality of surgical care, and associated components of perioperative productivity and staffing expenses. Objective of the Best Practice: Agitation and delirium in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) emerging from anesthesia can be minimized through proper patient and staff preparation and planning, specific anesthetic drug selection and timing, and minor modification of environmental factors. Using the protocol developed at Bayne-Jones Army Community Hospital (BJACH) for anesthetizing patients with PTSD, hospital staff can provide the safest and highest-quality surgical experience for this patient cohort in a manner which concurrently minimizes disruptions to planned surgical pavilion throughput and unplanned staff overtime expenses. Background: Anesthesia and post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) staff members at BJACH noticed a disturbing pattern in the first half of 2012, following the return of one of Fort Polk’s primary combat units from Afghanistan. While generalized harmless disorientation and restlessness are seen in a small percentage of the general population when emerging from anesthesia (easily managed in PACU), five combat veterans newly-returned from Afghanistan demonstrated battlefield-specific combat behaviors when becoming semilucid in PACU. These patients yelled fire team orders, screamed of “incoming RPGs,” looked around frantically for their battle-buddy, pulling at PACU monitoring equipment, oxygen tubes, urinary drainage catheters, and intravenous medication lines. These patients tried to get out of bed to aid their downed comrades, putting great stress on surgical repair and stitches, and risking fall injury. Staff interventions were met with physical violence and “combatives” maneuvers, putting both staff and patients at great risk of injury. Traditionally-effective PACU nursing interventions such as sedative medications, narcotic pain medications, continuous verbal reorientation and reassurance, and even giving “direct orders” to the patients proved ineffective. A sedative traditionally used on occasion in PACU for patient agitation (benzodiazepines) actually worsened the situation by paradoxically increasing delirium. These issues also caused distress to adjacent patients, separated only by privacy curtains in the open-bay PACU. Four of the five patients eventually responded to additional medications (approaching the threshold for potentially necessitating an unplanned overnight admission), but their PACU discharge was delayed by 75 to 120 minutes (an 83-133% increase over anticipated PACU stay of 90 minutes). One of the five patients did require unplanned admission for overnight observation due to the interventions required to safely placate him. In addition, the management of these unanticipated PTSD issues led to a reduction in operating room throughput and productivity, caused by the logjam created in the small PACU by the PTSD patients' significantly delayed discharge. The customary PACU nurse: patient ratio was unfavorably impacted due to the unanticipated acuity of the PTSD patients, thus reducing the PACU’s ability to accept other postoperative patients from the operating room in a timely manner. Anesthetists were required to stay longer in the PACU to assist with their post-operative patient (beyond the time normally needed to give report and transfer patient care to the PACU nurse), thus delaying their availability to begin the next anesthetic scheduled for their particular operating room. This 1 further delayed the surgical throughput. Staff RNs were required to stay beyond end-of-shift due to the delayed discharge of the PTSD patients, causing unplanned overtime expense. Concerned by these trends, the anesthesia and PACU staffs began to brainstorm alternative ways to prevent and/or effectively treat post-anesthesia “combat” PTSD symptoms in consultation with a BJACH clinical psychologist. The chief of anesthesia (a veteran of two overseas combat tours) contacted several peers at other military hospitals, as did other staff anesthetists. Not a single hospital had an anesthesia protocol to use with combat-veteran PTSD patients; neither did the Veterans Administration. This writer reflected back to his personal experience since 9/11 at various military medical centers with a significant number of combatwounded soldiers (including Walter Reed, Landstuhl, and Bethesda), and was unable to recall PTSD-specific anesthesia technique in use, in formal research, or under discussion. The Army anesthesia consultant had no PTSD-specific protocol or “best practice” to suggest, and knew of none under research or development. The Army Graduate Program in Nurse Anesthesia (USAGPAN) had neither faculty nor students currently researching this issue. The PACU chief nurse contacted several nursing peers at other hospitals, and also came up empty-handed. The anesthesia and PACU staffs decided to research all Food and Drug Administrationapproved usages for drugs currently on the anesthesia formulary, especially those in what could be considered “approved but seldom-used” categories, looking for a possible way to pharmacologically prophylax against PTSD post-emergence delirium. In addition, an exhaustive literature search revealed a huge void on this particular topic. Literature Review: The body of scientific knowledge on PTSD is replete with information on causes, symptoms, and therapeutic strategies in general; however, there is essentially no professional literature specific to anesthesia techniques tailored for patients with PTSD. Similarly the anesthesia literature contains numerous references to commonly seen, benign, and easily-managed disorientation experienced by a small percentage of the general population while emerging from anesthesia. In contrast just two references were discovered which discussed anesthesia and PTSD patients, and which were only peripherally helpful. The first reference (McGuire, 2012) addresses risk factors and incidence rates, but does not suggest specific anesthetic techniques for PTSD patients. The other reference (Wilson & Pokorny, 2012) provides a broad review of military anesthetists’ experiences with emergence delirium, and only begins to hint at potential anesthetic techniques optimized for PTSD patients. Implementation Methods: The anesthesia staff used medications already on the hospital formulary, in ways approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and in consultation with a hospital clinical psychologist. There was no differentiation between control and experimental groups. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required for this informal project, nor was anything beyond the standard anesthesia consent required. 2 During the preoperative patient consultation and teaching, conducted several days prior to surgery, anesthesia and nursing providers began to pay particular attention to patients' (and spouses’ if present) body language, looking for signs suggestive of hyperarousal or self-harm. Questions about recent onset of sleep disturbances and/or nightmares were added to the patient preoperative questionnaire. Some medications currently on the patient's profile, especially certain antidepressants and Prazosin (for nightmares) raised a high degree of PTSD suspicion, even if the patient did not have a formal PTSD diagnosis. Patient spontaneous verbal report of nightmares, whether on Prazosin or not, also served as a warning sign. Preoperative teaching, presented in a gentle, supportive, and nonjudgmental manner, included topics of PTSD flashbacks and how staff would care for the patient if they felt threatened. On the day of surgery, all team members involved in the pre-identified potential PTSD patient's care were briefed on the need to conscientiously minimize environmental stimuli normally found in a typical operating room (harsh bright lights, multiple conversations taking place simultaneously, clanging instrument trays, enforcing quiet in the operating room while anesthesia was being induced); similar considerations were taken in the PACU regarding lighting, ambient noise, conversational tones, nearby foot traffic, and liberal use of pain medication. Several other soldiers from the patient's unit were present in the PACU, on stand-by if needed for the patient's reorientation, reassurance, and safety. Unless contraindicated by a co-existing medical condition or allergy, the selection and timing of specific anesthesia drugs anticipated to lessen/eliminate PTSD symptoms (already on formulary, and already as approved by the FDA) included intraoperative dexamethasone steroid, liberal injection of subcutaneous local anesthesia by the surgeon pre-incision, and no intraoperative or postoperative administration of benzodiazepines. Small intraoperative doses of ketamine and droperidol were given. One primary modification featured intraoperative administration of clonidine, a sympatholytic drug which decreases the "fight-or-flight" response by blocking release of endogenous norepinephrine catecholamine. The other primary modification combined inhalational anesthetic gas (at reduced concentration) with continuous intravenous administration of diprivan (the primary anesthesia induction agent). This was done to minimize the risk of emergence delirium, sometimes seen in the general population following a gas-only anesthetic. The final implementation component utilized the theory of consistency, a key feature of outpatient PTSD therapy. On the day of surgery, all efforts were made to assign to the patient's care the same anesthetist and nurse who conducted the preoperative teaching consultations. In addition, several soldiers from the patient’s unit accompanied the patient on the day of surgery, providing an additional sense of support, camaraderie, and safety. They received a debriefing 3 Q&A prior to departure; they were encouraged to monitor and seek help if they perceived PTSD behaviors in themselves or platoon mates with no stigma attached. In summary, the protocol consists of preoperative identification of at-risk patients, maximum reduction of controllable environmental stimuli, use and specific timing of selected anesthesia medications, patient and staff education, and applying consistency. None of these components created any additional expenses. The only additional administrative requirement was coordinating with the patient’s unit to have several soldiers accompany the patient on day of surgery. Results: The preliminary experience with this BJACH project (N = 1) was accepted for publication last year (Lovestrand, Phipps, & Lovestrand, 2013). Since then, approximately 40 more PTSD patients were anesthetized using this protocol at BJACH with 100% success. Anesthesia staff, PACU staff, and patients are universally pleased with the preliminary outcomes. There has been no discernible combat PTSD anesthesia emergence agitation, no staff or patient safety issues, no delays in discharge from PACU, no slowdown in operating room throughput attributable to PTSD-related logjam in the PACU, no PTSD-associated RN overtime expense, no unplanned overnight admissions, and no reports of untoward post-discharge issues. The BJACH anesthesia department was recently asked by the Army anesthesia consultant to develop a local standard operating procedure for Army Medical Command review. Conclusions: (1). This measurable, efficient, and effective outcomes-based protocol, developed at BJACH, requires minimal adjustment to standard perioperative practices with no increase in cost, utilizes drugs already on the typical anesthesia formulary in ways which are considered current standard of care, and has universal applicability to both the military and civilian healthcare systems. Patient and staff safety and satisfaction are positively impacted by the protocol, the patient receives a comfortable and high-quality anesthetic, and PTSD-related disruptions to perioperative productivity and nursing payroll budgets are greatly minimized through this innovative yet simple care plan; (2). A current BJACH anesthesia staff member transfers this summer to a large military medical center. He plans to seek IRB approval for a formal study of BJACH's protocol, utilizing experimental and control groups with double-blind data gathering; (3). The protocol was developed at a small Army community hospital which saw ~20 patients per operating room per year with pre-existing PTSD. A large tertiary facility with high-acuity patients, such as San Antonio Military Medical Center (with 28 operating rooms), might see > 600 PTSD surgical patients in a year. If validated through formal research, extrapolating the application of this simple and anecdotally-effective PTSD anesthesia protocol across the entire Military Health System, Veterans Administration Health System, and private sector could yield significant improvements in overall satisfaction, safety, quality of surgical care, and associated perioperative administrative and staffing aspects of this patient cohort. 4 References Lovestrand, D., Phipps, P. S., & Lovestrand, S. (2013). Posttraumatic stress disorder and anesthesia emergence. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists Journal, 81, 199-203. McGuire, J. M. (2012). The incidence of and risk factors for emergence delirium in U.S. military combat veterans. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing, 27, 236-245. Wilson, J. T., & Pokorny, M. E. (2012). Experiences of military CRNAs with service personnel who are emerging from general anesthesia. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists Journal, 80, 260-265. 5