constructivism as applied to PBL - The Essential Handbook for GP

advertisement

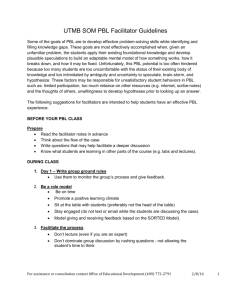

Constructivism as a Learning Theory as Applied to Problem-Based Learning (PBL) By Shane Beggan, GP In this article, I will introduce you to the theory of Constructivism with some attempt at critically evaluating it. I will then show you how you can develop PBL based on constructivist principles. Introduction to constructivism In 1710, two philosophers, an Italian named Vico and an Irishman, named Berkeley, separately made deplorable assertions that went against the grain of thousands of years of ancient philosophy. They dared to fundamentally change the concept of what knowledge is and what it means to exist. The human mind can only know what it constructs for itself and to be able to say something exists it must be first perceived by the human mind (von Glaserfeld, 2007). These bold thinkers portrayed the early beginnings of constructivism. A constructivist theory of cognition was first described by Piaget (von Glaserfeld, 1989), who described how learners construct their knowledge by building on what they already know and have experienced. The way we interpret this experience ‘constitutes the only world we consciously live in’ (von Glaserfeld, 1995, p.18). The breadth and depth of literature dedicated to constructivism is mind-boggling and the nature of the theory’s application to education I have found complex and difficult to understand. This is perhaps because it is more of a philosophy of human knowledge than a blueprint for learning and as such is open to many interpretations. Philips (1995) describes constructivism as a ‘secular religion’ with many sects, each with a distrust of the other on the basis of differences in their beliefs, underlining the lack of cohesiveness among constructivist theorists. There are several described forms of constructivism such as cognitive as explored by Piaget, social constructivism as pioneered Vygotsky often cited as an alternative to Piaget but is arguably complementary (Shayer, 2003) and radical constructivism as coined by its originator von Glaserfeld (2001) which builds on Piaget’s life work. From an education perspective, the philosophical basis for constructivism theory can be difficult to understand and apply to learning but a more pragmatic philosophy has been neatly distilled into three propositions as described by Savery and Duffy (2001): 1. We cannot separate how we learn from what we learn: the interaction between learner and the environment is what forms understanding. 2. The learner needs a goal or ‘puzzle’ to stimulate learning (cognitive conflict): these goals can be both practical i.e. to pass an exam; and intellectual i.e. to 1 wish to advance one’s knowledge and understanding. The new information needs to be reconciled with prior knowledge and discrepancies addressed to inform new understanding. 3. Social interaction is key to developing knowledge: sharing our individual understanding with others allows our understanding to be tested and creates further puzzles to continue to stimulate learning. These propositions take elements from both cognitive and social constructivism, which certainly helps clarify the approach that can be adopted in an education context without overcomplicating things with complex philosophical ideologies. Davis and Sumara (2002) in fact argue that constructivist theory was never intended to be a practical guide for educators, describing it ‘not educational in any pragmatic sense’ and contrast this with behaviourist theory which ‘speaks more directly to the concerns of educators’ (Davis & Sumara 2002 p.417). Gordon (2009) argues however that behaviourism is open to criticism in its application to education just in the same way as constructivist theory. He asserts difficulties with a constructivist approach arise from a lack of coherent literature on what it means to be constructivist and a lack of engagement with the skilled educators who use it without necessarily having a deep understanding of the philosophical base. Gordon (2009) makes a real attempt to develop a ‘pragmatic constructivism’ where there is interconnectedness between educational theory and practical teaching. He argues that educational theory has a lot to learn form the skilled constructivist teachers and both can influence each other to create mutual benefits. Gordon’s (2009) attempt to synthesise the main theories of constructivism into common shared values to provide a pragmatic approach is an attractive one and helps me as an educator to think practically about how I can enhance learning and understanding in my teaching. He uses an example where a teacher realises her constructivist approach failed because she had not made the overall big picture clear at the outset. This highlights the importance, for constructivists, of examining the topic or concept as a whole first before dividing into its component parts (Gordon 2009). There are other interpretations of the educational application of constructivism such as Caine and Caine’s 12 principles of constructivism (Caine & Caine, 1991). They provide a detailed view of how the body, brain and mind participate in the learning process. This certainly provides a comprehensive and thought provoking approach with practical tips for teachers to improve the effectiveness of their teaching but the statements are wide-ranging and could cover many different educational approaches, which may be at odds with each other. There are similarities with Savery and Duffy’s (2001) propositions within the 12 principles, for example, ‘learning involves both 2 focused attention and peripheral perception’ [the interaction between learner and environment] and ‘learning is enhanced by challenge and inhibited by threat’ [cognitive conflict] (Caine & Caine, 1991, p.7). Neither is a model for how to teach but are more of an approach, which I think importantly focuses on the learner rather than the teacher. This in contrast to traditional higher education approaches, which tend to focus on the teacher (Tynjälä, 1999). Lebow (1993, p.5) contrasts traditional educational values like ‘replicability’ and ‘control’ against what he describes as primary constructivist values which include ‘collaboration, personal autonomy, generativity, reflectivity, active engagement, personal relevance and pluralism’. These values are used by Savery and Duffy (2001) to provide an instructional framework for problembased learning (PBL), a learning approach that is often considered a model example of a constructivist theory in practice (Savery & Duffy 2001). It could be argued that Lebow’s (1993) values are not purely constructivist ideas and overlap other educational theories such as andragogy (Knowles, 2005), Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (Maslow, 1987) and Gibbs Reflective Cycle (Gibbs, 1998). This is probably inevitable with theories that explore how we learn as adults and shift focus to the learner. Constructivism and Problem-Based Learning Constructivism is not for everyone and much of the literature is critical of the approach. It seems various interpretations of the term within an educational context has led to confusion about the best ways to use constructivist theory to plan effective teaching (Taber, 2011). One of the arguments against social constructivism is that it leads to ‘group thinking’ where a few extroverts dominate the group and the quieter students feel compelled to conform or the learners develop misunderstandings or misconceptions which go left unchecked (Kozloff, 1998). Research by Kirschner et al (2006) suggests that constructivist approaches to learning such as problem-based learning (PBL), do not work as well as direct instruction for changing long-term memory. The also argue that unguided instruction which occurs in self-directed learning (SDL) within PBL environments can lead to misconceptions or knowledge that is fragmented. This is a potential risk but from my own experience of a PBL medical degree, there was little evidence of minimal or unguided instruction but mostly skilful facilitation by tutors to prevent this very problem. It is this facilitation by experienced teachers that prevents a dominant individual dictating where the learning goes and guides students to avoid misconceptions and misunderstandings. Hemlo-Silver et al (2006) in fact published a paper in riposte to Kirschner et al’s (2006) controversial article. They argued that PBL and inquiry 3 learning (IL) are both ‘powerful and effective models for learning’ (Hemlo-Silver et al 2006, p. 99) because they use ‘scaffolding’ to guide learners though complex tasks and learning goals. They also highlight how PBL emphasises soft skills important to a constructivist approach such SDL and collaboration. Problem-based learning and PBL curricula From my experience of a pure PBL medical degree at Liverpool, as a learner it feels more natural to construct my knowledge within the context of my clinical practice and life experience and to collaborate with colleagues, students and patients to test and develop my knowledge. PBL has its origins in 1969 in McMaster University medical school in Canada and has been used as the instructional method in over 60 medical schools including Harvard University (Hendry et al, 1999; Neville, 2009). Hendry et al (1999) concludes that an optimal PBL teaching environment includes: 1. Realistic problems 2. Tutor facilitation that support reflection and cooperation 3. Sufficient scheduled time for independent study 4. Formative and summative assessment that is aligned with learning issues, problem packages and other integrated, interactive teaching sessions. These incorporate some of the values like cognitive conflict and goals within Savery and Duffy’s (2001) propositions for constructivism. It also matches my own experience of tutor facilitation to support learning alluded to earlier. Clearly, as already discussed with Kirschner et al’s (2006) paper, PBL is not without controversy and a pilot systematic review by Newman (2003) concluded there were no comprehensive systematic reviews to say PBL is effective. Neville (2009) however argues the conflicting studies in the literature could not be judged without delving into all methodologies and heterogeneous definitions of PBL. Dolmans (2003) also took exception to Newman’s approach to systematic reviews, suggesting inclusion criteria were too rigorous, by including only randomised control trials or experimental studies meant many educational studies were omitted. She argued that to believe only experimental studies could yield useful reliable evidence was to lack insight into educational research. Dolmans’s (2003) and Neville’s (2009) assertion that a constructivist approach to educational research, using different methodological approaches is likely to yield improvements, makes sense. There are so many variables within PBL environments that to rely only on quantitative studies misses out valuable narrative studies that can help build on its effectiveness as a teaching environment (Dolman 2003). This view is also supported by Oliver-Hoyo and Allen (2006) who talk about triangulation of research where qualitative and quantitative research is combined in an attempt to reduce bias. 4 Colliver (2002) warns that theories underpinning PBL are at best ‘conjecture’ rather than evidence-based and that medical faculties should beware of using it to inform practice. He reiterates his previous concerns that constructivism ‘muddles the distinction between philosophy and science, between episte- mology and learning’ (Colliver 2002 p.1217), which reflects earlier comments about the confusing nature of the literature on constructivism. In an earlier critical review, Colliver (2000) also concludes that educational theory is poorly supported by research where PBL is concerned and that there is little evidence it is better than traditional models in medical education. He argues that the outcomes in terms of knowledge base and clinical acumen do not justify the significant resources being ploughed into PBL curricula. Colliver (2003) does acknowledge ‘PBL may provide a more challenging, motivating, and enjoyable approach to medical education’ (Colliver 2000 p.266) but gives no credence to these benefits. It seems intuitive that even if PBL has limited evidence to support its superiority to traditional courses, if the outcomes are similar, then the above benefits are worth having. Hendry et al (1999) suggests that if the only difference in outcomes of a PBL course is greater student satisfaction, this alone is enough to warrant the adoption of PBL. He also cites research which shows medical students on PBL courses have a greater interest in curriculum content, have a more positive outlook on their course and enjoy it more compared to traditional courses. From my own perspective, there were three difficulties I encountered with PBL: 1. Uncertainty about depth required when addressing learning objectives generated during small group work. 2. An over-emphasis on self-directed learning (SDL) in basic sciences 3. A lack of explicit curriculum to refer to and compare goals with There are different methods of PBL described in the literature, some using more SDL than others. Barrows (1986) proposed a taxonomy of PBL to help developers of curricula understand which methods would suit their students best. In my course, closed-loop problem-based learning was used beginning with small-group analysis of a carefully worded case to generate learning objectives, followed by a period of SDL and completed by a re-evaluation of learning in the last group session. My experience of uncertainty about depth was assuaged to a large degree by facilitation at the second group session. Here the facilitator guided everyone towards what an acceptable level of detail should be. The process of deciding how much depth was necessary during the self-directed learning developed skills needed as an independent practitioner. Albanese and Mitchell (1993) identified research, which 5 showed that PBL students often feel uncomfortable about getting the right breadth and depth of content. One of the ways this was addressed was to reassure student that their objectives were compared against faculty objectives in line with the curriculum and any gaps are addressed in the small groups (Albanese & Mitchell, 1993). There needs to be a balance between fostering SDL and the right amount of guidance and one of the areas I found this difficult was in basic sciences such as anatomy and physiology. A Dutch study by Prince et al (2003) found no difference in anatomy knowledge between PBL and traditional medical courses. Albanese and Mitchell also discuss poorer performance of PBL students in basic science tests compared to traditional curricula. They argue however that this is not always the case and may depend on variations in PBL as well as differences in students’ approach to SDL. There was perhaps an over reliance on SDL at Liverpool and as certain subjects like anatomy and basic sciences had optional attendance, they were sometimes not given due attention. A recent curriculum review report by Liverpool Medical School (University of Liverpool 2014) announced that PBL was being discontinued as the main curriculum design. They cited the main reasons as inadequacies in basic science knowledge such as anatomy and physiology and uncertainty and confusion about the level of depth required. They give a few reasons as follows for why the PBL curriculum has become unsustainable (University of Liverpool 2014): 1. Increased medical students numbers 2. Variation in quality of PBL facilitators 3. Lack of clinical academics and NHS consultants offering to become PBL facilitators 4. Difficulties in designing learning outcomes and assessment blue print due to the lack of structure in the curriculum The curriculum at Liverpool was designed as a spiral PBL curriculum designed to construct and layer learning within the basic sciences across all 5 years but this meant clinicians felt students weren’t adequately grounded in these subjects once they started clinical placements. In addition, as there were no explicit learning objectives for placements, clinicians were unclear what they were supposed to be covering. As discussed earlier, good facilitation to guide students and avoid pitfalls is important, so it is understandable that variation in quality would be a cause for concern. There is no consensus, evidence-based or otherwise on what is the best way to shape a curriculum so curricula tend to be based more on ideology than hard evidence (Grant J 2010). PBL curricula have allowed educators to move away from thinking only about content and more about the delivery and application of knowledge (Prideaux, 6 2007). Bligh et al (2001) developed the PRISM acronym to assimilate the qualities required for twenty-first century medical school curricula. This stands for Product focused; Relevant; Inter-professional; Shorter, smaller; Multi-site and Symbiotic. PBL courses which focused on outcomes, working with other health professionals and advocating small group working across multiple sites fit this model of curriculum development well (Prideaux 2007). The outcomes of medical curricula need to be broad overview statements rather than narrower specific knowledge, skills and attitudes (Harden 2002). These need to be aligned with the learning objectives which are generated by students in group work in each part of the course and with assessments which are used to test whether these outcomes have been achieved (Biggs 2003). The use of outcomes has been criticised as a ‘teacher-controlled ideology’ (Rees 2004), which seems plausible but there is a need to satisfy the requirements of the GMC to allow doctors to reach an acceptable standard (Harden et al, 1999). If PBL curricula are designed in the right way they can foster greater learner co-operation and empowerment, rather than focusing purely on outcomes (Rees, 2004). PBL and other learning theories Although PBL is most associated with constructivism, there are other learning theories which overlap such as andragogy and reflective practice. Knowles (2005) describes six assumptions about how adults learn: 1. The need to know 2. The learners self-concept 3. The role of experience 4. Readiness to learn 5. Orientation to learning 6. Motivation In andragogy there is a move away from dependent learning as in pedagogy to selfdirected learning [changing the self-concept] which as discussed earlier forms a major part of constructivism in PBL courses (Knowles 2005). The role of experience is emphasised as a rich resource for learning in a similar way that learning is constructed on our previous experiences and knowledge (von Glaserfeld 1989). PBL uses cases or problems in the context of real-life so that learning can be seen as relevant to future practice and goals. This creates the readiness to learn as described by Knowles (2005). Knowles (2005) also states that people are performance-centred in their orientation to learning so in the case of medical students they want to be become competent doctors and achieve their full potential. 7 Gibbs reflective cycle (Gibbs 1988) was developed as a tool to help learners to reflect on their experience and evaluate it in a structured way. Where constructivism says that knowledge is built on existing knowledge and experience, it is the reflection on new experience that develops learning and understanding. The new experiences create cognitive conflict, which drives learning (Savery & Duffy, 2001). Schön (1991) describes how practitioners allow themselves to experience puzzlement and reflect on this puzzlement to apply previous knowledge and understanding to create new knowledge. This is much like the proposition by Savery and Duffy (2001) described earlier in constructivist theory but underlines how it is actually reflection that creates the new knowledge. Conclusion Constructivism has useful application to education and particularly in PBL environments. Above all it focuses on the learner and how they learn, something which Andragogy also does in its assumptions about learners. Clearly for constructivism to work well in PBL courses there must be the necessary support like good facilitators, adequate scaffolding and explicit learning outcomes within a wellstructured curriculum (Hemlo-Silver et al 2006). Camp et al (1996) produced a list of the values, which a ‘pure’ PBL course should afford the learner, namely: problembased learning is active; adult-oriented; problem-centred; student-centred; collaborative; integrated; interdisciplinary; utilizes small groups; and operates in a clinical context. This approach is not just constructivism but takes elements of adult learning principles. No learning theory is a panacea and will not fit every purpose, so for example even pedagogy has a place for certain elements of course content and could be viewed as the other end of the spectrum to andragogy (Mehay, R et al, 2012, p.115). Knowles (1989) argues that learning theories should not be viewed an ideology that must be adhered to at all costs. The arguments about which learning theory is better is not the question; there is general agreement that focusing on the learner is paramount but a better question may be, how can elements from different learning theories be used to enhance the way educators’ facilitate learning. Acknowledgements This article has been modified from an assignment submitted by the author as part of their Post Graduate Certificate in Medical Education, University of Leeds. Many thanks for guidance received from Drs. Jane Kirby and Ramesh Mehay, Academic Unit of Primary Care, University of Leeds. Acknowledgements also to the Yorkshire and the Humber Deanery for funding the certificate. 8 References Albanese, M. and Mitchell, S. 1993. Problem-based learning. Academic Medicine. 68(1),pp.52-81. Barrows, H. 1986. A taxonomy of problem-based learning methods. Medical Education. 20(6),pp.481-486. Bligh, J. et al. 2001. PRISMS: new educational strategies for medical education. Med Educ. 35(6),pp.520-521. Caine, R. and Caine, G. 1991. Making connections. Alexandria, Va.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Camp, G. 1996. Problem-Based Learning: A Paradigm Shift or a Passing Fad?. Medical Education Online. 1(0). Colliver, J. 2002. Educational Theory and Medical Education Practice. Academic Medicine. 77(12, Part 1),pp.12171220. Colliver, J. 2000. Effectiveness of Problem-based Learning Curricula. Academic Medicine. 75(3),pp.259-266. Davis, B. and Sumara, D. 2002. Constructivist discourses and field of education: Problems and possibilities. Educational Theory. 52(4),pp.409-428. Dolmans, D. 2003. The effectiveness of PBL: the debate continues. Some concerns about the BEME movement. Med Educ. 37(12),pp.1129-1130. Gibbs, G. 1988. Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods. [London]: FEU. Gordon, M. 2009. Toward A Pragmatic Discourse of Constructivism: Reflections on Lessons from Practice. Educational Studies. 45(1),pp.39-58. Grant, J. 2010. Principles of Curriculum design. In: Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. Swanwick, T. ed.. Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Pub. pp1-15. Harden, R. 2002. Learning outcomes and instructional objectives: is there a difference?. Med Teach. 24(2),pp.151155. Hendry, G. et al. 1999. Constructivism and Problem-based Learning. Journal of Further and Higher Education. 23(3),pp.369-371. Hmelo-Silver, C. et al. 2007. Scaffolding and Achievement in Problem-Based and Inquiry Learning: A Response to Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006). Educational Psychologist. 42(2),pp.99-107. Kirschner, P. et al. 2006. Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching. Educational Psychologist. 41(2),pp.75-86. Knowles, M. et al. 2005. The adult learner. Amsterdam: Elsevier. Knowles, M. 1989. The modern practice of adult education- From Pedagogy to Andragogy. New York, N.Y.: Cambridge, The Adult Education Co. Kozloff, M. 1998. Constructivism in Education: Sophistry for a New Age. [online]. Available from: http://pennance.us/home/documents/Constructivism.pdf [Accessed February 5, 2015]. Lebow, D. 1993. Constructivist values for instructional systems design: Five principles toward a new mindset. ETR&D. 41(3),pp.4-16. Maslow, A. 1987. Motivation and personality 3rd ed. New York: Harper & Row. Mehay, R. et al. 2012. Five Pearls of Educational Theory. In: Mehay, R. ed. The essential handbook for GP training and education.. London: Radcliffe. p.115. Neville, A. 2009. Problem-Based Learning and Medical Education Forty Years On. Med Princ Pract. 18(1),pp.1-9. Newman, M. et al. 2004. Responses to the pilot systematic review of problem-based learning. Med Educ. 38(9),pp.921-923. Oliver-Hoyo, M. and Allen, D. 2006. The Use of Triangulation Methods in Qualitative Educational Research. Journal of College Science Teaching. Jan/Feb, [online]. 35(4),pp.42-47. Available from: http://www.nsta.org/publications/news/story.aspx?id=51319 [Accessed January 30, 2015]. Phillips, D. 1995. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: The Many Faces of Constructivism. Educational Researcher. 24(7),pp.5-12. Prideaux, D. 2007. Curriculum development in medical education: From acronyms to dynamism. Teaching and Teacher Education. 23(3),pp.294-302. Prince, K. et al. 2003. Does problem-based learning lead to deficiencies in basic science knowledge? An empirical case on anatomy. Med Educ. 37(1),pp.15-21. Rees, C. 2004. The problem with outcomes-based curricula in medical education: insights from educational theory. Med Educ. 38(6),pp.593-598. 9 Savery, J. and Duffy, T. 2001. Problem Based Learning: An instructional model and its constructivist framework [online]. Available from: http://jaimehalka.bgsu.wikispaces.net/ [Accessed January 25, 2015]. Schlön, D. 1995. The reflective practitioner. Aldershot: Arena, 1995. Shayer, M. 2003. Not just Piaget; not just Vygotsky, and certainly not Vygotsky as alternative to Piaget. Learning and Instruction. 13(5),pp.465-485. Taber, K. 2011. Constructivism as Educational Theory: Contingency in learning and optimally guided instruction. In: Educational Theory. Hassaskhah, J. ed.. New york: Nova Science Publishers. Tynjälä, P. 1999. Towards expert knowledge? A comparison between a constructivist and a traditional learning environment in the university. International Journal of Educational Research. 31(5),pp.357-442. University of Liverpool, 2014. Liverpool MBChB Curriculum 2014- Final Curriculum Review Report [online]. Available from: http://www.liv.ac.uk/medicine/curriculum-review [Accessed February 2, 2015]. von Glaserfeld, E. 2007. Aspects of constructivism. Vico, Berkeley, Piaget. In: Glasersfeld E. von, Key works in radical constructivism.. Rotterdam: Sense. von Glasersfeld, E. 1989. Cognition, construction of knowledge, and teaching. Synthese. 80(1),pp.121-140. von Glasersfeld, E. 1995. Radical constructivism. London: Falmer Press. von Glasersfeld, E. 2001. Radical constructivism and teaching. Prospects. 31(2),pp.161-173. 10