Hazelwood_Mine_Inquiry_Report_Part04_PF

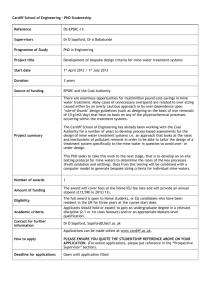

advertisement