Wyoming-Jones-Figueroa-Neg-UNLV-Round5

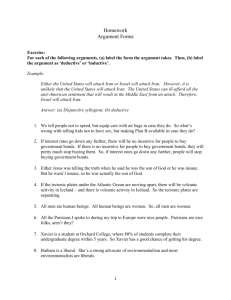

advertisement