Dystopian Literature

advertisement

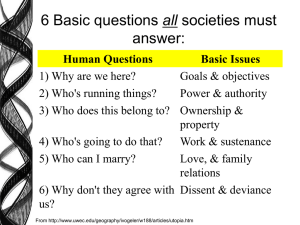

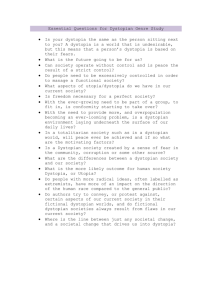

Dystopian Literature Genre: Close Study of Dystopian Genre The dystopic novel evinces a strong theme common in much science fiction and fantasy fiction, the creation of a future time (usually), when the conditions of human life are exaggeratedly bad due to deprivation, oppression or terror. This created society or ‘dystopia’ frequently constructs apocalyptic views of a future using crime, immorality or corrupt government to create or sustain the bad quality of people’s lives, often conditioning the masses to believe their society is proper and just, and sometimes perfect. It can provide space for heroism in disrupting the dystopian setting. Most dystopian fiction takes place in the future but often purposely develops contemporary social trends taken to extremes. Dystopias are frequently written as commentaries, as warnings or as satires, showing current trends extrapolated to nightmarish conclusions. A brief note on the etymology of ‘Dystopia’ The Oxford English Dictionary reports that the term ‘Dystopia’ was first used in the late 19th century by British philosopher John Stuart Mill. He also used Jeremy Bentham's synonym, ‘cacotopia’. The prefix caco means ‘the worst.’ Both words were created in apposition to utopia, a word coined by Sir Thomas Moore to describing an ideal place or society. DYSTOPIA: definition dys-/dus- (Latin/Greek roots: 'bad' or 'abnormal') + -topos (Greek root: 'place') = 'bad place' eu- (Greek root: 'good') / ou- (Greek root: 'not') + -topos (Greek root: 'place') = 'good/no place' dystopia n. an imaginary wretched place, the opposite of utopia utopia n. a place or state of ideal perfection, the opposite of dystopia Some writers see the difference between a Utopia and a Dystopia often lying in the reader/visitor's point of view: One person's heaven being another's hell. The History of Dystopian Literature The term "utopia" originated in the early 1500s as an idea created by Sir Thomas More and refers to a society where perfection and stability have been attained. Throughout history, though, many authors have taken that idea and used its exact opposite as a literary device to motivate their stories. The 'anti-utopias' or 'dystopias' take place in societies where the people live in constant fear and control of their governing body, live meaningless lives and have very little hope for any amount of change to take place. While dystopian literature really didn't come into the mainstream until the 20th century, the 19th also held a few stories of significant importance to the emergence of the genre. One of the most important was a novel written in 1863 by Jules Verne entitled Paris in the Twentieth Century. It tells the tale of a young man who has graduated college with a degree in literature; however all of the arts in Paris are government-controlled. Without being able to use what he learned in school to make a living for himself he finds he is running out of money and with no place to live. He is freezing to death at the end of the novel and walking the streets of Paris. There are mechanical wonders of all sorts, but nothing that will keep him warm and he becomes more and more delirious. He eventually dies after reflecting on how his society's lack of the arts ultimately led to the death of many innocent people. This dystopian epic paints the picture of a world without art and warns that it is a cold and mechanized future. In 1895, H.G. Wells wrote The Time Machine. The story tells the tale of a 19th century inventor who discovers the secrets of time travel. While his travels take him to various times in the future and some are wonderful, he ultimately ends up in a future where humanity has devolved into horrid creatures called the Morlocks. There is an upper class of humans in this same future, but they seem to be desensitized and highly uneducated because of years without war or challenges. The lower Morlocks, however, have become violent and aggressive beasts who attempt to kill everything they see. The story warns of the dangers of human class systems over centuries and the ability for man to be both angelic and hellish. The story, much like the society it details, begins in harmony and ends in disaster. One of the more modern examples of a dystopian epic in the 20th century was Anthony Burgesses' 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange. The novel takes place in an alternate-reality England where gangs roam the streets and rape and murder are a common occurrence. The main character is a leader of one of the gangs that terrorizes the innocence of England and cares nothing for people's emotions or property. By the end of the novel, however, the hero is arrested and taken to a secret government facility where he is brainwashed into being unable to think negative thoughts. The main character quickly discovers without the ability to defend himself or even posit a negative idea, that he is quickly swallowed up by the world he has helped create. This is a great example of a dystopian epic because Burgess is able to immerse the reader into a new world, with a new language and a character who has helped to create a society of terror. He is ultimately victimized by this same world and the cycle of a corrupted society becomes apparent. Dystopias have existed for as long as literature has been recorded, however people before the 1800s were less likely to write stories of hellish times for fear of retribution from their rulers. For instance, in Shakespeare's age, any slight against the king that would appear in a play could lead to the execution of the entire ensemble. For as long as man has dreamed of paradise, they have also dreaded utopia. Many ideas in the bible can be seen as dystopian, but are allowed to survive because of the overall positive message of the book. A story which showed the overall negative aspects of society would never have seen print. Works Cited: Frye, Roland Mushat. (1970). Shakespeare: The Art of the Dramatist. Houghton Mifflin Company. Boston. Greenblatt, Stephen. (2004) Will in the World. W.W. Norton and Company, New York, London. Gray, Terry A. "Mr. William Shakespeare and the Internet" 2008. MIT Tech. Project Muse. "English Literary History" 2008. John Hopkins University Press. Smith, David Nichol. "Eighteenth Century Essays on Shakespeare" 1903, J. MacLehose and Sons _________________________ o 0 o _________________________ A dystopia is the idea of a society in a repressive and controlled state, often under the guise of being utopian. Examples of dystopias are characterized in books such as Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four. Other examples include The Iron Heel, described by Erich Fromm as "the earliest of the modern Dystopian", and the religious dystopia of The Handmaid's Tale. Dystopian societies feature different kinds of repressive social control systems, various forms of active and passive coercion. Ideas and works about dystopian societies often explore the concept of humans abusing technology and humans individually and collectively coping, or not being able to properly cope with technology that has progressed far more rapidly than humanity's spiritual evolution. Dystopian societies are often imagined as police states, with unlimited power over the citizens. The word derives from Greek: δυσ-, "bad, hard" and Greek: τόπος, "place, landscape". It can alternatively be called cacotopia, or anti-utopia. Etymology The word dystopia represents a counterpart of utopia, a term originally coined by Thomas More in his book of that title completed in 1516. The first known use of dystopian, as recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary, is a speech given before the British House of Commons by John Stuart Mill in 1868, in which Mill denounced the government's Irish land policy: "It is, perhaps, too complimentary to call them Utopians, they ought rather to be called dys-topians, or caco-topians. What is commonly called Utopian is something too good to be practicable; but what they appear to favour is too bad to be practicable." Counter-utopia, anti-utopia Many dystopias found in fictional and artistic works present a utopian society with at least one fatal flaw, whereas a utopian society is founded on the good life, a dystopian society’s dreams of improvement are overshadowed by stimulating fears of the "ugly consequences of present-day behavior." People are alienated and individualism is restricted by the government. An early example of a dystopian novel is Rasselas (1759), by Samuel Johnson, set in Ethiopia. Society In the novel Brave New World, written in 1931 by Aldous Huxley, a class system is prenatally designated in terms of Alphas, Betas, Gammas, Deltas, and Epsilons. In We, by Yevgeny Zamyatin, people are permitted to live out of public view for only an hour a day. They are not only referred to by numbers instead of names, but are neither " but "ciphers". In the lower castes, in Brave New World, single embryos are "bokanovskified", so that they produce between eight and ninety-six identical siblings, making the citizens as uniform as possible. Some dystopian works emphasize the pressure to conform in terms of a requirement not to excel. In these works, the society is ruthlessly egalitarian, in which ability and accomplishment, or even competence, are suppressed or stigmatized as forms of inequality, as in Kurt Vonnegut's Harrison Bergeron. Similarly, in Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, the dystopia represses the intellectuals with particular force, because most people are willing to accept it, and the resistance to it consists mostly of intellectuals. Social groups Concepts and symbols of religion may come under attack in a dystopia. In Brave New World, for example, the establishment of the state included lopping off the tops of all crosses (as symbols of Christianity) to make them "T"s, (as symbols of Henry Ford's Model T). But compare Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale, wherein a Christianity-based theocratic regime rules the future United States. In some of the fictional dystopias, such as Brave New World and Fahrenheit 451, the family has been eradicated and continuing efforts are deployed to keep it from reestablishing itself as a social institution. In Brave New World, where children are reproduced artificially, the concepts "mother" and "father" are considered obscene. In some novels, the State is hostile to motherhood: for example, in Nineteen Eighty-Four, children are organized to spy on their parents; and in We, the escape of a pregnant woman from One State is a revolt. Nature Fictional dystopias are commonly urban and frequently isolate their characters from all contact with the natural world. Sometimes they require their characters to avoid nature, as when walks are regarded as dangerously anti-social in Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451. In Brave New World, the lower classes of society are conditioned to be afraid of nature, but also to visit the countryside and consume transportation and games to stabilize society.] A few "green" fictional dystopias do exist, such as in Michael Carson's short story "The Punishment of Luxury", and Russell Hoban's Riddley Walker. The latter is set in the aftermath of nuclear war, "a post-nuclear holocaust Kent, where technology has reduced to the level of the Iron Age" Politics In When the Sleeper Wakes, H. G. Wells depicted the governing class as hedonistic and shallow. George Orwell contrasted Wells' world to that depicted in Jack London's The Iron Heel, where the dystopian rulers are brutal and dedicated to the point of fanaticism, which Orwell considered more plausible. Whereas the political principles at the root of fictional utopias (or "perfect worlds") are idealistic in principle, intending positive consequences for their inhabitants, the political principles on which fictional dystopias are based are flawed and result in negative consequences for the inhabitants of the dystopian world, which is portrayed as oppressive. Dystopias are often filled with pessimistic views of the ruling class or government that is brutal or uncaring ruling with an "iron hand" or "iron fist". These dystopian government establishments often have protagonists or groups that lead a "resistance" to enact change within their government. Dystopian political situations are depicted in novels such as Parable of the Sower, Nineteen EightyFour, Brave New World and Fahrenheit 451; and in such films as Fritz Lang's Metropolis, Brazil, FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions, and Soylent Green. Economics The economic structures of dystopian societies in literature and other media have many variations, as the economy often relates directly to the elements that the writer is depicting as the source of the oppression. However, there are several archetypes that such societies tend to follow. A commonly occurring theme is that the state plans the economy, as shown in such works as Ayn Rand's Anthem and Henry Kuttner's short story The Iron Standard. A contrasting theme is where the planned economy is planned and controlled by corporatist and fascist elements. A prime example of this is reflected in Noman Jewison's 1975 Rollerball film. Some dystopias, such as Nineteen Eighty-Four, feature black markets with goods that are dangerous and difficult to obtain, or the characters may be totally at the mercy of the state-controlled economy. Such systems usually have a lack of efficiency, as seen in stories like Philip Jose Farmer's Riders of the Purple Wage, featuring a bloated welfare system in which total freedom from responsibility has encouraged an underclass prone to any form of antisocial behavior. Kurt Vonnegut's Player Piano depicts a dystopia in which the centrally controlled economic system has indeed made material abundance plentiful, but deprived the mass of humanity of meaningful labor; virtually all work is menial and unsatisfying, and only a small number of the small group that achieves education is admitted to the elite and its work. Even in dystopias where the economic system is not the source of the society's flaws, as in Brave New World, the state often controls the economy. In Brave New World, a character, reacting with horror to the suggestion of not being part of the social body, cites as a reason that everyone works for everyone else. Other works feature extensive privatization and corporatism, where privately owned and unaccountable large corporations have effectively replaced the government in setting policy and making decisions. They manipulate, infiltrate, control, bribe, are contracted by, or otherwise function as government. This is seen in the novel Jennifer Government and the movies Alien, Robocop, Visioneers, Max Headroom, Soylent Green, THX 1138, WALL-E and Rollerball. Rule-bycorporation is common in the cyberpunk genre, as in Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (made into the movie Blade Runner) and Snow Crash'. Caste systems In dystopian literature the advanced technology is controlled exclusively by the group in power, while the oppressed population is limited to technology comparable to or more primitive than what we have today. In order to emphasize the degeneration of society, the standard of living among the lower and middle classes is generally poorer than that of their equivalents in contemporary industrialized society. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, for example, the Inner Party, the upper class of society, also has a standard of living that at least appears lower than the upper classes of today. In contrast to Nineteen Eighty-Four, in Brave New World and Equilibrium, people enjoy much higher material living standards in exchange for the loss of other qualities in their lives, such as independent thought and emotional depth. In Ypsilon Minus by Herbert W. Franke, people are divided into numerous alphabetically ranked groups. Similarly, in Brave New World, people are divided into castes ranging from Alpha-Plus to Epsilon, with the lower classes having reduced brain function and conditioning to make them satisfied with their position in life. _________________________ o 0 o _________________________ Commonly Used Dystopias Totalitarian dystopias As the name suggests, totalitarian societies utilises total control over and demands total commitment from the citizens, usually hiding behind a political ideology. Totalitarian states are, in most cases, ruled by party bureaucracies backed up by cadres of secret police and armed forces. The citizens are often closely monitored and rebellion is always punished mercilessly. Stories taking place in totalitarian dystopias usually depict the hopeless struggle of isolated dissidents. Totalitarian dystopias have, in general, dark psychological depths and strong political qualities. Hitler's Third Reich and Stalin's Soviet Union were real examples of such societies. Bureaucratic dystopias Bureaucratic dystopias, or technocratic dystopias, are strictly regulated and hierarchical societies, thus related to totalitarian dystopias. Where totalitarian regimes strive to achieve complete control, bureaucratic regimes only strive to achieve absolute power to enforce laws. When totalitarian regimes tend to found their own laws, bureaucratic regimes tend to defend old laws. The law always seem to stand in conflict with rational thinking and human behaviour. To change status quo, even everyday procedures, is a long and difficult process for the citizens. It goes without saying such dystopias have strong satirical qualities and to some extent surreal qualities as well. Cyberpunk dystopias A cyberpunk society is essentially a drastically exaggerated version of our own. Cyberpunk is a heterogeneous genre, but most dystopias have the following settings: the technological evolution has accelerated, environmental collapse is imminent, the boards of multi-national corporations are the real governments, urbanisation has reached new levels and crime is beyond control. Important, but not necessary essential, concepts in cyberpunk are cybernetics, artificial enhancements of body and mind, and cyberspace, the global computer network and ultimate digital illusion. Cyberpunk stories are often street-wise and violent. It is debatably the most influential dystopian genre ever. Crime dystopias Crime dystopias may have different settings. These societies have been infested with grave criminality and the authorities are about to lose control or have already lost it. This criminality may span from street crime to organised crime, more seldom governmental crime such as corruption and abuse of power. The authorities often use drastic and inhumane measures to fight the moral decay, perhaps out of desperation, perhaps out of necessity. The society is often in imminent danger of becoming totalitarian. Crime dystopias are not-seldom political statements, usually of a radical and controversial nature. Overpopulation dystopias The population of the world has grown dramatically and the limited resources of our planet are exhausted. Mankind is living in despair and society is in imminent danger of becoming or has already become social-Darwinistic. There is an enormous wealth gap between the rich and the poor, and military and police are used to control the starving masses. There are many parallels between overpopulation dystopias and cyberpunk dystopias, especially when speaking of environment and urbanisation. This kind of dystopia is rather rare, which is surprising: it may become an imminent problem in the near future. Leisure dystopias Leisure dystopias are probably best described as utopias gone wretched or failed paradiseengineering projects. In these societies, all problems have been solved, at least officially, and all citizens are living in wealth and happiness. Unfortunately, this is often achieved by suppressing individuality, art, religion, intellectualism and so on and so forth. Conditioning, consumption, designer-drugs, light entertainment and similar methods are widely used in order to combat existential misery. Conformity is encouraged as it makes it easier to control the population. The government's means of control are always of a very subtle nature and open repression is basically non-exist. Leisure dystopias are not very common nowadays, probably as Utopia is almost extinct as concept. Feminist dystopia As the name suggests, feminist dystopias deal with oppression of women. The feminist dystopia is built on patriarchal structures and the role of woman has been diminished, e.g. to house-keeping and breeding. The society is often totalitarian or at least crypto-totalitarian, sometimes with more or less obvious parallels to fascism as represented in Mussolini's Italy and Hitler's Germany. To one degree or another, all dystopias are patriarchal, but in feminist dystopias it is explicit. This genre is debatably one of the most innovative dystopian genres nowadays but has received a remarkably small amount of attention, all too small in my opinion. _________________________ o 0 o _________________________ Critical background for teaching about dystopias Characteristics of dystopias Dystopias usually express original and innovative ideas, thus forming a heterogeneous genre. Still, there are some common characteristics. Settings Dystopian depictions are always imaginary. Although Hitler's Third Reich and Stalin's Soviet Union certainly qualify as horror societies, they are still not dystopias. The very purpose of a dystopia is to discuss, not depict contemporary society or at least contemporary mankind in general. Stories like Taxi Driver and Enemy of the State may have dystopian qualities, but they still depict reality, however twisted the prerequisites of those stories might be. Dystopian depictions may borrow features from reality, but the purpose is to debate, criticise or explore possibilities and probabilities. Dystopia is not really about tomorrow, but rather about today or sometimes yesterday. Nevertheless, dystopian stories take place in the future in most cases. The year 1984 may have past, but George Orwell's horror story described a plausible future scenario when it was published for the first time in 1949 and it may still come true in a not too distant future. Interesting exceptions from this rule are uchronias, so called What-if? stories, like Fatherland. Dystopias have always been a powerful rhetorical tool. They have been used and abused by politicians, thus making dystopian stories controversial. The anti-totalitarianism in Nineteen Eighty-Four is explicit, but the anti-Reaganism in Neuromancer is implicit. The war-ridden world in the Mad Max trilogy is obviously a Dystopia, but it would be ridiculous to call it a political statement, although one can claim it is a warning regarding the dangers of anarchy and SocialDarwinism. Themes The leitmotif of dystopias has always been oppression and rebellion. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the pseudo-communistic party Ingsoc's oppression of the people is obvious, but the multi-national mega-corporations' oppression of the people in Neuromancer is more subtle. The oppressors are usually more or less faceless, as in THX-1138, but may sometimes be personified, as in Blade Runner. The oppressors are almost always much more powerful than the rebels. Consequently, dystopian tales often become studies in survival. In Neuromancer it is simply a question of staying alive, in Brave New World it is a question of staying human. In Nineteen Eighty-Four it is even a matter of remaining an individual with own thoughts. The hero, because it is usually not a heroine, often faces utter defeat or sometimes Pyrrhic victory, a significant feature of dystopian tales. As the citizens of dystopian societies often live in fear, they become paranoid and egoistical, almost like hunted animals. Dystopian citizens experience a profound feeling of being monitored, shadowed, chased, betrayed or manipulated. The factors which trigger this paranoia may be very evident and explicit like in Brazil or more diffuse and implicit like in Blade Runner. The most extreme example of paranoia is probably the Thought Police and the thought-crime concept in Nineteen Eighty-four. As a result of this fearful atmosphere, dystopian heroes are not seldom monsters in many respects. The dehumanisation of society may also be connected to the benefits and hazards of technological progress. Cyberspace cowboys refer to their bodies as "meat" and blade runners hunt artificial, but completely sentient beings like animals. In Dystopia, the borderline of humanity is often blurred and the very concept of humanity distorted. Finally, dystopian stories tend to explore the concept of reality. Rick Deckard in Blade Runner is not sure if he is a human being or a bio-mechanical replica. Case in Neuromancer sometimes cannot distinguish cyberspace from reality. Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four is forced to learn that two plus two make five. In many dystopian tales the people in general and the heroes in particular get manipulated beyond reality. Aesthetics Dystopian stories frequently take place in landscapes which diminish people, like large cities with mastodontic architecture or vast wastelands devastated by war and pollution. Dystopian societies are usually, but far from always, battered and worn-out. They may be colorless like Nineteen Eighty-Four or kaleidoscopic like Blade Runner, but always visually obtrusive. For uncertain reasons, dystopian movies often use film noir features like dim rooms, rain wet asphalt, disturbing contrasts, symbolic shadows etc. Unproportionaly much of the action takes place during night in many dystopian stories. Possibly, this reflects the thematic relationship between dystopian fiction and film noir. Generally speaking, the environment plays an active role in dystopian depictions. The environment is not only a fancy background, but emphasises the message. A prominent example is Blade Runner: there can be no doubt in the viewer that USA has become completely commercialised and that the world is in a state of terminal decay. _________________________ o 0 o _________________________ Characteristics of dystopian fiction The following is a list of common traits of dystopias, although it is not definitive. Most dystopian films or literature includes at least a few of the following: a hierarchical society where divisions between the upper, middle and lower class are definitive and unbending. a nation-state ruled by an upper class with few democratic ideals state propaganda programs and educational systems that coerce most citizens into worshipping the state and its government, in an attempt to convince them into thinking that life under the regime is good and just strict conformity among citizens and the general assumption that dissent and individuality are bad a fictional state figurehead that people worship fanatically through a vast personality cult, such as 1984’s Big Brother or We‘s The Benefactor a fear of the world outside the state a common view of traditional life, particularly organized religion, as primitive and nonsensical a penal system that lacks due process laws and often employs psychological or physical torture constant surveillance by state police agencies the banishment of the natural world from daily life a back story of a natural disaster, war, revolution, uprising, spike in overpopulation or some other climactic event which resulted in dramatic changes to society a standard of living among the lower and middle class that is generally poorer than in contemporary society a protagonist who questions the society, often feeling intrinsically that something is terribly wrong because dystopian literature takes place in the future, it often features technology more advanced than that of contemporary society To have an effect on the reader, dystopian fiction typically has one other trait: familiarity. It is not enough to show people living in a society that seems unpleasant. The society must have echoes of today (see Rosenblatt; Pike), of the reader's own experience. If the reader can identify the patterns or trends that would lead to the dystopia, it becomes a more involving and effective experience. Authors can use a dystopia effectively to highlight their own concerns about societal trends. George Orwell apparently wanted to title 1984 1948, because he saw this world emerging in austere postwar Europe. As fictional dystopias are often set in a future projected virtual time and/or space involving technological innovations not accessible in actual present reality, dystopian fiction is often classified generically as science fiction, a subgenre of speculative fiction. Back stories Because a fictional universe has to be constructed, a selectively told backstory of a war, revolution, uprising, critical overpopulation, or other disaster is often introduced early in the narrative. This results in a shift in emphasis of control, from previous systems of government to a government run by corporations, totalitarian dictatorships or bureaucracies; or from previous social norms to a changed society and new (and often disturbing) social norms. Because dystopian literature typically depicts events that take place in the future, it often features technology more advanced than that of contemporary society. Hero Unlike utopian fiction, which often features an outsider to have the world shown to him, dystopias seldom feature an outsider as the protagonist. While such a character would more clearly understand the nature of the society, based on comparison to his society, the knowledge of the outside culture subverts the power of the dystopia. When such outsiders are major characters—such as John the Savage in Brave New World—their societies cannot assist them against the dystopia. The story usually centers on a protagonist who questions the society, often feeling intuitively that something is terribly wrong, such as Guy Montag in Ray Bradbury's novella Fahrenheit 451, Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four, or V in Alan Moore's V for Vendetta. The hero comes to believe that escape or even overturning the social order is possible and decides to act at the risk of his own life; this may appear as irrational even to him, but he still acts. The hero's point of view usually clashes with the others' perception, most notably in Brave New World, revealing that concepts of utopia and dystopia are tied to each other and the only difference between them lies on a matter of opinion. Another popular archetype of hero in the more modern dystopian literature is the Vonnegut hero, a hero who is in high-standing within the social system, but sees how wrong everything is, and attempts to either change the system or bring it down, such as Paul Proteus of Kurt Vonnegut's novel Player Piano or Winston Niles Rumfoord in The Sirens of Titan. The Domination is perhaps unusual in featuring members of the upper caste of the dystopian society (the von Shrakenbergs, Myfwany, Yolande Ingolfsson, various Draka military members) as among the protagonists although serfs (Marya and Yasmin, from among conquered people) questioning that society are also included, along with international enemies of that dystopian society (such as Lefarge). This may be an example of the anti-hero. Conflict In many cases, the hero's conflict brings him to a representative of the dystopia who articulates its principles, from Mustapha Mond in Brave New World to O'Brien in Nineteen Eighty-Four. There is usually a group of people somewhere in the society who are not under the complete control of the state, and in whom the hero of the novel usually puts his hope, although often he or she still fails to change anything. In Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four they are the "proles" (Latin for "offspring", from which "proletariat" is derived), in Huxley's Brave New World they are the people on the reservation, and in We by Zamyatin they are the people outside the walls of the One State. In Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury, they are the "book people" past the river and outside the city. Climax and dénouement The story is often (but not always) unresolved even if the hero manages to escape or destroy the dystopia. That is, the narrative may deal with individuals in a dystopian society who are unsatisfied, and may rebel, but ultimately fail to change anything. Sometimes they themselves end up changed to conform to the society's norms, such as in With Folded Hands, by Jack Williamson. This narrative arc to a sense of hopelessness can be found in such classic dystopian works as Nineteen Eighty-Four. It contrasts with much fiction of the future, in which a hero succeeds in resolving conflicts or otherwise changes things for the better. Destruction The destruction of dystopia is frequently a very different sort of work than one in which it is preserved. Indeed, the subversion of a dystopian society, with its potential for conflict and adventure, is a staple of science fiction stories. Poul Anderson's short story "Sam Hall" depicts the subversion of a dystopia heavily dependent on surveillance. Robert A. Heinlein's "If This Goes On—" liberates the United States from a fundamentalist theocracy, where the underground rebellion is organized by the Freemasons. Cordwainer Smith's The Rediscovery of Man series depicts a society recovering from its dystopian period, beginning in "The Dead Lady of Clown Town" with the discovery that its utopia was impossible to maintain. Although these and other societies are typical of dystopias in many ways, they all have not only flaws but exploitable flaws. The ability of the protagonists to subvert the society also subverts the monolithic power typical of a dystopia. In some cases the hero manages to overthrow the dystopia by motivating the (previously apathetic) populace. In the dystopian video game Half-Life 2 the downtrodden citizens of City 17 rally around the figure of Gordon Freeman and overthrow their Combine oppressors. Destruction of the fictional dystopia may not be possible, but—if it does not completely control its world—escaping from it may be an alternative. In Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, the main character, Montag, succeeds in fleeing and finding tramps who have dedicated themselves to memorizing books to preserve them. But ironically, the dystopian society in Fahrenheit 451 is destroyed in the end — by nuclear missiles. In the book Logan's Run, the main characters make their way to an escape from the otherwise inevitable euthanasia on their 21st birthday (30th in the later film version). Because such dystopias must necessarily control less of the world than the protagonist can reach, and the protagonist can elude capture, this motif also subverts the dystopia's power. In Lois Lowry's The Giver the main character Jonas is able to run away from 'The Community' and escapes to 'Elsewhere' where people have memories. Sometimes, this escape leads to the inevitable: the protagonist making a mistake that usually brings about the end of a rebel society, usually living where people think is a legend. This concept is brought to life in Scott Westerfeld's novel Uglies. The main character accidentally brings the government into the secret settlement of the Smoke. She then infiltrates the government to escape, but chooses to join the society for the greater good. _________________________ o 0 o _________________________ This is an attempt to pin-point important landmarks and possible influences in dystopian fiction. Needless to say, Dystopia is almost as old as Utopia. However, the elaborate or modern dystopian depiction was born in the late 18th century. Before this time, dystopian depictions were merely rhetorical tools and intellectual experiments. 1868 John Stuart Mill uses the term dystopia in a parliamentary speech, possibly the first recorded use of the term. 1879 The famous American inventor Thomas Edison introduces the electric bulb. It is an important landmark in the electrical revolution, since it brings the electric wonder to private homes. Many a utopian writer finds inspiration in this technological development, but also many a dystopian writer. In The Begum's Fortune by Jules Verne, utopian and dystopian societies are contrasted. Whether it can be regarded as the first modern dystopia is debatable, but it certainly is an important forerunner. 1880 In USA, the first industrial execution method since the guillotine is introduced: the electric chair. 1885 The publication of the first modern post-holocaust depiction: After London by Richard Jefferies. 1895 Guglielmo Marconi introduces the first practical application of radio technology, the telegraph. It marks the beginning of the mass communication era and entails a dramatic evolution of communication and information technologies. The Lumière brothers construct the cinematograph and exhibit the first motion picture. Until the break-through of television after World War II, the motion picture will be the most effective means of propaganda. 1897 Henri Becquerel discovers the phenomenon radioactivity. The dangerous potential of this discovery is recognised almost directly. 1898 H.G. Wells' ground-breaking novel War of the Worlds, the first depiction of an alien invasion of Earth, is published. 1899 The publication of the novels The Story Of The Days To Come and When The Sleeper Wakes by H.G. Wells. They are debatably the first modern dystopias per se, probably the first elaborately ideological dystopias, and definitely the first anti-capitalistic dystopias. 1901 Guglielmo Marconi establishes the first transatlantic wireless connection, thus indirectly enabling effective global trade and warfare in the future. 1903 The Wright brothers perform the first successful flight in an aeroplane. It lasts for 12 seconds and 40 meters. The practical implementation of aircraft will revolutionise communications and warfare the following decades. 1908 The publication of H.G. Wells' The War In The Air, the first prediction of air raids against cities. 1909 Jack London's The Iron Heel reaches the bookshelves and consolidates ideological themes in dystopian fiction. A manifesto by the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti marks the birth of a controversial and short-lived art movement: Futurism. Its worship of dynamics and machines will indirectly influence dystopian visions for decades. 1911 Only eight years after the accomplishment of the Wright brothers, aeroplanes are used in combat for the first time. Italian pilots bomb two oases near Tripolis in North Africa; needless to say, the targets are civilian. 1914 In a haze of war romanticism, the European powers engage in the Great War; not only the first world war, but also the first industrialised war. It lasts for four years and results in more than 10 million dead people. The world will never be the same again. The same year, The World Set Free by H.G. Wells is published. It is the first prophecy of devastating nuclear wars that will end human civilisation. The publication of Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Herland, debatably the first feministic dystopia. 1915 Chemical weapons are deployed in battle for the first time: the German army uses chlorine gas near Ypres in Belgium. 1917 A revolution in Russia gives the Bolsheviks an opportunity to seize power. Soon, they begin to call themselves Communists, and their radical political program will gradually evolve into a totalitarian nightmare. It will end over 70 years after the revolution. 1918 The Spanish Influenza, the worst pandemic ever next to the Black Death, claims more than 21 million lives, more than every 100th human being. 1919 The Bauhaus school of design is founded in Germany. It will influence art and design in a futuristic direction, and indirectly also science fiction. In the long run, the influences will be most prominent in dystopian fiction. 1920 Karel Čapek's play R.U.R. introduces the term robot and the modern robot concept, and is the first elaborate depiction of a machine take-over. Čapek's robots can also be seen as the first androids: they are in fact organic. 1921 The publication of the earliest major cyborg novel: The Clockwork Man by E.V. Odle. The protagonist's life is regulated by a clockwork mechanism built into his head. 1924 Yevgeny Zamiatin's My (English title: We), the first totalitarian dystopia as well as the first critical comment on the future of USSR, is published. It will serve as inspiration for Aldous Huxley and George Orwell. In the essay Daedalus, or Science and The Future, J.B.S. Haldane prophesies with remarkable precision about different kinds of genetic engineering in the future. It served as inspiration for e.g. Aldous Huxley's Brave New World. 1925 In Italy, the Fascists seize power, and implement the first truly totalitarian system; USSR will soon follow. Many intellectuals, even in democratic countries, praise Mussolini's new order. Franz Kafka's world-famous novel Der Prozess is published. The pessimistic perspective on modern society basically revolutionises literary fiction. It influences dystopian fiction in many respects, albeit usually indirectly; some intellectuals will even label the novel per se as dystopian. The Paris World's Fair can be regarded as the official starting-point of art deco. This aesthetic current will be dominant in design and architecture for decades, including such expressions in science fiction cinema. Illustrative modern examples are Cloud City in The Empire Strikes Back and the Tyrell Pyramid in Blade Runner. 1926 The Scotsman John Baird conducts the first successful television transmission, thus introducing the most effective means of mass propaganda and mass marketing so far in human history. Within a decade, regular television transmissions have begun in London, Paris, Berlin and New York. Première of Fritz Lang's mastodontic movie Metropolis, the first serious science fiction movie, as well as the first dystopian movie. It sets a new standard for cinema in general and futuristic cinema in particular. 1929 Capitalistic break-down: On the so-called Black Sunday, 80 million dollars disappear from the American economy due to stock exchange mania. It entails severe depression, social unrest and indirectly also autocratic take-overs around the world. 1930 In the novel City Of The Living Dead by Laurence Manning and Fletcher Pratt, artificial illusionary worlds à la virtual reality or cyberspace are introduced. Interestingly enough, the novel focuses on the escapist dangers of such technology. 1932 The publication of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, the first depiction of failed paradise-engineering. Among many other things, it basically introduces the themes of mass culture and technology abuse in dystopian fiction, as well as scientific concepts such as designer drugs, conditioning and cloning. Carl W Spohr's short story The Final War prophesies that the world will be divided between two superpowers, and that the invention of the atomic bomb will entail nuclear deterrence strategies. The story ends with the annihilation of mankind. 1933 The National Socialists seize power in Germany and implement an autocratic and militaristic order, soon to become elaborately totalitarian. The nightmare ends 12 years later in the ruins of Berlin. Fritz Lang's movie Das Testament des Dr Mabuse is banned by the new regime in Germany. Tellingly, it depicts how a criminal organisation attempts to seize power with terror methods. 1934 Première of the German propaganda film Triumf des Willens by the controversial filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. It will influence dystopian nightmare visions of totalitarian systems for many decades to come. 1936 A rebellion by military units in Spain triggers the first armed ideological conflict: the Spanish Civil War. The Fascist side introduces barbarian war methods in Europe, methods which previously had been reserved for the colonies; the most horrifying novelty is air raids against civilian targets, e.g. in Guernica. More than one million people die, and Fascism triumphs. The war entails a dangerous polarisation between Fascism and Communism. The first public trials against alleged traitors are staged in USSR, which marks the beginning of Stalin's terror era. It lasts until the dictator's death in 1953 and costs at least 20 million lives. The first modern use of the term android in Jack Williamsson's The Cometeers. 1938 Orson Welles causes public panic in USA with a realistic radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds, and effectively illustrates the potential of mass media manipulation. The publication of A.G. Street's Already Walks Tomorrow, probably the first elaborate depiction of environmental collapse. John W Campbell's short story Who Goes There? introduces the stealthy alien concept. It raises little interest, but will later be filmatised as The Thing From Another World in 1951 and The Thing in 1982. 1939 Hitler's Third Reich attacks Poland and triggers the most devastating conflict so far in human history, World War II. More than 40 million people die in five years. Especially the German scientists excel in inventing advanced military technology which will claim many lives in the future, e.g. jet fighters and directed missiles. The publication of Raymond Chandler's first major detective story: The Big Sleep. Chandler's novels, and the film adaptation, will influence dystopian fiction with their potent mixes of lonely detectives, realistic approaches, urban settings, societal critique, harsh dialogue etc. 1941 The première of John Huston's film noir classic The Maltese Falcon, an adaptation of a novel by Dashiell Hammett. Film noir in general and this movie in particular will influence dystopian cinema, especially the art deco aesthetics, the visual settings, the cinematic techniques and the concrete narratives. 1942 The Holocaust is outlined in the infamous Wanzee conference. The first industrial genocide in human history will claim the lives of 6 million Jews. All in all, the terror machinery claims at least 12 million lives, including communists, dissidents, gypsies, homosexuals and disabled. The first nuclear reactor is constructed in USA for military purposes. The full scope of the hazards with civilian nuclear power will not be recognised until much later. 1943 COLOSSUS, the first electronic computation machine is completed in Great Britain. It is in fact more advanced than ENIAC, but it will remain a military secret for decades. 1945 The Manhattan Project is completed, and USA deploys nuclear weapons against human populations for the first time. One bomb in Hiroshima and another in Nagasaki’s claim at least half a million lives, including the victims of the lingering radiation. Only four years later, USSR detonates its first atom bomb, and the nuclear arms race is a fact. Only a few months after Hitler's death, the first uchronia, i.e. alternative history, concerning a Third Reich victory is published: Laszlo Gaspar's Mi, I. Adolf. 1946 In the Nuremberg Trials, the full scope of the totalitarian horrors in the Third Reich are recognised. The first truly global peace organisation, the United Nations, is founded. USA and USSR immediately begin to manipulate and weaken the organisation. The first official electronic computation machine, ENIAC, is completed in USA. The first real computer, EDSAC, is completed only three years later in Great Britain. 1948 The publication of Norbert Wiener's cross-disciplinary work Cybernetics: Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. From a scientific point of view, Man has become Machine. The term cybernetics is, by the way, Wiener's own invention. 1949 After a bloody civil war, the Communists proclaim the People's Republic of China. Exactly how many lives the revolution claims the next two decades will never be certain, but it is probably at least 20 million, hypothetically ten times as many. George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-four, the most elaborately anti-totalitarian dystopia and the politically most influential dystopia of all times, is published. It advances and consolidates the dystopian themes of systematic oppression and mind control. Until the making of Blade Runner, it is basically the sole Dystopia prototype. 1950 Alan Turing defines the so-called Turing Test, the philosophical foundation of artificial intelligence theory. A new science is born, and the following decades many a scientist will claim to have created an intelligent computer. 1952 USA detonates the first hydrogen bomb at Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific, thus increasing the scope of nuclear mass destruction dramatically. The heart pacemaker, the first implanted mechanical body enhancement, is introduced. Debatably, this event marks the beginning of the post-human era. The Space Merchants by Fredrick Pohl Cyril Kornbluth, the first elaborate satire over commercialism and consumerism, is published, and introduces concepts such as corporate dominion, corporate overexploitation and corporate wars. The publication of Kurt Vonnegut's Player Piano, debatably the first depiction of a pseudo-utopian society run by a computer. The term dystopia is popularised in Quest For Utopia by Glenn Negley and J. Max Patrick. 1953 Watson and Crick unravels the structure of DNA. From a scientific point of view, Man has become Computer: the Code has been revealed and the Code can be reprogrammed. The publication of Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, possibly the most intellectually advanced dystopian satire, together with Nineteen Eighty-four. In any case, it certainly contributed to the intellectual integrity of dystopian fiction. Filmed by François Truffaut in 1966. 1954 A TV play adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-four starring Peter Cushing entails anxious questions in the British parliament. 1955 Première of Don Siegel's Invasion Of The Body Snatchers, an adaptation of a novel by Jack Finney, the first major depiction of a stealthy alien take-over. 1957 USSR launches the first man-made satellite, Sputnik I. The space race is a fact, and it engenders a rapid technological evolution. Among many other things, satellites will enable new means of communication, mass culture, surveillance and warfare. The publication of Nevil Shute's novel On The Beach, made into a movie in 1959 starring e.g. Gregory Peck. It was not the first depiction of nuclear holocaust horrors, but the first one which had a strong emotional impact on the main-stream audience. 1959 The publication of Robert Heinlein's pro-militaristic and anti-democratic novel Starship Troopers, which engenders a heated debate among science fiction writers. Harry Harrison is one of Heinlein's prominent antagonists. 1962 The Cuba crisis almost triggers a nuclear war between USA and USSR. If mankind would have survived a full-scale nuclear conflict is uncertain. Philip K Dick advances the uchronia in The Man In The High Castle, the first uchronian novel to receive the prestigious Hugo award. 1965 In the novel Dune, Frank Herbert basically introduces dystopian themes in space opera. 1966 Make Room, Make Room by Harry Harrison, the first major over-population dystopia, is published; later to be adapted for the silver screen under the title Soylent Green in 1973. D.F. Jones's novel Colossus, adapted for the silver screen in 1969, is probably the first depiction of a global take-over attempt by military computers. The concept will later be advanced in the Terminator and Matrix movies. 1967 The first heart transplant operation is performed, and human beings suddenly become sets of organic spare parts. The anthology Dangerous Visions, edited by Harlan Ellison, marks the birth of a new science fiction movement: New Wave. It only lasts for a few years, but expands the science fiction concept by breaking many taboos. 1968 Stanley Kubrick's and Arthur C Clark's 2001: A Space Odyssey sets new visual and thematic standards for science fiction in general and science fiction cinema in particular. It advances the artificial intelligence concept and introduces more realistic and conceivable space programs. Philip K Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? advances the android concept and raises disturbing questions about human identity. 1969 USA implements the first Moon landing, the Apollo 11 expedition. A few more manned Moon landings will follow, but the costly Vietnam war will soon put an end to these grand projects. In USA, the first primitive computer network, a nuclear defence application, is constructed. The event will entail a dramatic evolution of computer technology, perhaps most notably the development of the first global computer network, internet. John Brunner advances the over-population theme in Stand on Zanzibar. 1971 The first space station, the Soviet Salyut 1, is constructed and put into operative use. Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess hits the theatres and engenders a furious debate, especially in Great Britain. The movie basically introduces the theme of urban anarchy in dystopian fiction. Robert Wise's The Andromeda Strain, based on a novel by Michael Crichton, popularises the modern pandemic horror theme. The première of Douglas Trumbull's sadly underestimated Silent Running, the first environment-conscious science fiction movie. David Rorvik popularises the modern cyborg concept in As Man Becomes Machine. 1972 John Brunner advances the dystopian theme of environmental collapse in The Sheep Look Up. 1973 In Japan Sinks, Sakyo Komatsu advances the apocalyptic theme in science fiction, especially the social and psychological aspects. 1974 John Carpenter's obscure low-budget comedy Dark Star is probably the first non-romantic and non-heroic movie about space exploration. Screen-writer Dan O'Bannon will later advance the concept dramatically in Alien. 1975 Altair 8800 is the first personal computer to be produced in fairly high quantity. Thus, the personal computer industry is launched, a technological development that will inspire the cyberpunk movement. The same year, John Brunner basically introduces the modern cyberspace concept in The Shockwave Rider. 1976 A new potential plague is recognised: the Ebola haemorrhagic fever. The first outbreak occurs in Sudan, shortly followed by an outbreak in Zaire. Within the next decades, more outbreaks will occur, some of them with a mortality rate of 70-90 %; as a comparison, the mortality rate of the Black Death was 30-75 % K. Eric Drexler popularises the term nano-technology in his book Engines of Creation. 1977 The publication of Joe Haldeman's brutal anti-war novel The Forever War, debatably the first serious depiction of possible space war horrors; also, it can be seen as a critical comment on Starship Troopers. Together with Alien, it basically demonises space adventures. The punk album God Save The Queen by Sex Pistols reaches the hit lists and marks the official birth of punk music and punk subculture. This revolution of pop culture will influence the cyberpunk movement. 1979 In Three-Mile Island, USA, the first serious incident at a nuclear power plant occurs. In Iran, a fundamentalist revolution entails the first proclamation of an elaborate theocracy since the proclamation of the Vatican state in 1929. Ridley Scott's famous horror movie Alien hits the box office, and changes the look and feel of space adventures dramatically. 1981 A new disease is recognised in USA, although yet not named: AIDS. Exactly when this lethal virus began to circulate is uncertain, though; it probably occurred for the first time in the late 1960s or early 1970s. George Miller's Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior advances the break-down of civilisation in the first movie into Social-Darwinist anarchy, and sets a new standard for post-apocalyptic depictions. 1982 Ridley Scott's Blade Runner sets a whole new standard for science fiction, especially visually, and influences the coming cyberpunk movement immensely. It will engender debates on e.g. hyper-technology and urbanisation for decades to come. As a spin-off effect, it also popularises Philip K. Dick's works. Steven Lisberger's Tron, immensely underestimated at its time, advances the cyberspace concept. 1984 William Gibson's Neuromancer is published and marks the birth of the influential cyberpunk movement. It also inspires science, engenders debate, revitalises dystopian fiction, popularises the cyberspace concept, and consolidates the themes of corporate dominion and hyper-technology in modern science fiction. James Cameron's The Terminator hits the box office and reanimates the old dystopian machine horrors, later to be continued in the Matrix movies. George Orwell's dreaded year passes, and some people claim that Aldous Huxley's nightmare prophecy is more accurate. Première of Michael Radford's ambitious adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-four, starring John Hurt and Richard Burton. 1985 Terry Gilliam's Brazil reboots Kafkaesque themes in dystopian fiction and basically defines the visual standards for tech noir; compare with The City Of Lost Children and Dark City. 1986 In Chernobyl, USSR, the first nuclear power plant catastrophe occurs. 1987 The publication of Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale; not the first feminist dystopia, but the first one which gains recognition. It popularises feminist theory in science fiction and advances the concept of modern theocracies in dystopian fiction. In the novel Consider Phlebas, Iain M. Banks basically integrates the utopian-dystopian complexity in the space opera genre. Paul Verhoeven's RoboCop modernises the anti-capitalistic satire with cyberpunk concepts. 1988 Katsuhiro Omoto's Akira popularises anime and manga outside Japan, cultural expressions which will continue to influence dystopian fiction, albeit mainly on aesthetic levels. 1989 The fall of the Berlin Wall is a fact, and it will soon be followed by the fall of the USSR. It entails a political vacuum and an uncertain future. 1990 The publication of the first dystopian steampunk novel: The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling. 1992 Neal Stephenson reboots and advances the cyberpunk genre in Snow Crash. Robert Harris advances the uchronia in Fatherland, basically the only best-selling uchronia so far. 1993 Graphical user interfaces make internet practically accessible to the public. Possibly, future history books will claim that it entailed social, psychological and perceptual changes. 1997 The première of the first major genetic-engineering dystopia, Andrew Niccol's Gattaca. 1998 Almost 40 years after the publication of Robert Heinlein's Starship Troopers, Paul Verhoeven's controversial adaptation engenders a new debate. 1999 The Matrix by the Wachowski brothers revitalises the fading post-cyberpunk current in dystopian fiction. 2001 The largest terrorist attack ever occurs in New York. The terrorists achieve their goals: wide-spread paranoia, non-democratic tendencies and illegal war campaigns. Possibly, the event will mark the end of Western hegemony in future history books. 2003 The first taikonaut in space. Possibly, the event will mark the beginning of a new space race in future history books. The publication of Margaret Atwood's Oryx and Crake, a radical renewal of the bioengineering horror concept. List of Dystopian Texts 19th century A Sojourn in the City of Amalgamation, in the Year of Our Lord, 19-- (1835) by Oliver Bolokitten Erewhon (1872) by Samuel Butler. The Republic of the Future (1887) by Anna Bowman Dodd Caesar's Column (1890) by Ignatius L. Donnelly Pictures of the Socialistic Future (1890) by Eugen Richter The Time Machine (1895) by H. G. Wells When The Sleeper Wakes (1899) by H. G. Wells 20th century 1900s The First Men in the Moon (1901) by H. G. Wells The Iron Heel (1908) by Jack London Lord of the World (1908) by Robert Hugh Benson The Machine Stops (1909) by E. M. Forster 1910s Metamorphosis (1915) by Franz Kafka 1920s We (1921) by Yevgeny Zamyatin 1930s Brave New World (1932) by Aldous Huxley It Can't Happen Here (1935) by Sinclair Lewis War with the Newts (1936) by Karel Čapek Anthem (1938) by Ayn Rand Out of the Silent Planet (1938) by C.S. Lewis 1940s Darkness at Noon (1940) by Arthur Koestler "If This Goes On—" (1940) by Robert A. Heinlein Kallocain (1940) by Karin Boye Perelandra (1943) by C.S. Lewis That Hideous Strength (1945) by C.S. Lewis Bend Sinister (1947) by Vladimir Nabokov Ape and Essence (1948) by Aldous Huxley Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) by George Orwell 1950s Limbo, (vt. Limbo 90) (1952) by Bernard Wolfe Player Piano (also known as Utopia 14) (1952) by Kurt Vonnegut Fahrenheit 451 (1953) by Ray Bradbury One (also published as Escape to Nowhere) (1953) by David Karp Bring the Jubilee (1953) by Ward Moore Love Among the Ruins (1953) by Evelyn Waugh Lord of the Flies (1954) by William Golding The Chrysalids (1955) by John Wyndham Atlas Shrugged 1957 by Ayn Rand 1960s Facial Justice (1960) by L. P. Hartley "Harrison Bergeron" (1961) by Kurt Vonnegut A Clockwork Orange (1962) by Anthony Burgess The Wanting Seed (1962) by Anthony Burgess Cloud On Silver (US title Sweeney's Island) (1964) by John Christopher Nova Express (1964) by William S. Burroughs The Penultimate Truth (1964) by Philip K. Dick Epp (1965) by Axel Jensen Logan's Run (1967) by William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson Make Room! Make Room! (1966) by Harry Harrison Stand on Zanzibar (1968) by John Brunner The Jagged Orbit (1969) by John Brunner The White Mountains (1967) by John Christopher The City of Gold and Lead (1968) by John Christopher The Pool of Fire (1968) by John Christopher 1970s This Perfect Day (1970) by Ira Levin The Lathe of Heaven (1971) by Ursula K. Le Guin The Sheep Look Up (1972) by John Brunner Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said (1974) by Philip K. Dick The Shockwave Rider (1975) by John Brunner High-Rise (1975) by JG Ballard The Dark Tower[22] (1977) - unfinished, attributed to C.S. Lewis, published as The Dark Tower and Other Stories Alongside Night (1979) by J. Neil Schulman Ypsilon Minus (1979) by Herbert W. Franke 1980s The Running Man (1982) by Stephen King under the pseudonym Richard Bachman Sprawl trilogy: Neuromancer (1984), Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988) by William Gibson The Handmaid's Tale (1985) by Margaret Atwood Ender's Game (1985) by Orson Scott Card Obernewtyn Chronicles (1987–2008) by Isobelle Carmody The Domination (1988) by S. M. Stirling V for Vendetta (1988-1989) by Alan Moore (writer), and David Lloyd (illustrator). When the Tripods Came (1988) by John Christopher 1990s Fatherland (1992) by Robert Harris The Children of Men (1992) by P.D. James The Giver (1993) by Lois Lowry Gun, with Occasional Music (1994) by Jonathan Lethem The Diamond Age, or A Young Lady's Illustrated Primer (1995) by Neal Stephenson Underworld (1997) by Don DeLillo Battle Royale (1999) by Koushun Takami 21st century 2000s Noughts and Crosses (2001) by Malorie Blackman Feed (2002) by M. T. Anderson The House of the Scorpion (2002) by Nancy Farmer Jennifer Government (2003) by Max Barry The City of Ember (2003) by Jeanne DuPrau Oryx and Crake (2003) by Margaret Atwood Manna (2003) by Marshall Brain Knife edge (2004) by Malorie Blackman The Bar Code Tattoo (2004) by Suzanne Weyn Cloud Atlas (2004) by David Mitchell Checkmate (2005) by Malorie Blackman Divided Kingdom (2005) by Rupert Thomson Never Let Me Go (2005) by Kazuo Ishiguro Uglies (2005) by Scott Westerfeld Pretties (2005) by Scott Westerfeld Specials (2006) by Scott Westerfeld Armageddon's Children (2006) by Terry Brooks Bar Code Rebellion (2006) by Suzanne Weyn The Book of Dave (2006) by Will Self Day of the Oprichnik (День Опричника) (2006) by Vladimir Sorokin Genesis (2006) by Bernard Beckett Sunshine Assassins (2006) by John F. Miglio The Pesthouse (2007) by Jim Crace Extras (2007) by Scott Westerfeld Gone (2008) by Michael Grant The Host (2008) by Stephenie Meyer Double Cross (2008) by Malorie Blackman The Hunger Games (2008) by Suzanne Collins The Forest of Hands and Teeth (2009) by Carrie Ryan The Maze Runner (2009) by James Dashner The Year of the Flood (2009) by Margaret Atwood Shades of Grey (2009) by Jasper Fforde Catching Fire (2009) by Suzanne Collins 2010s The Envy Chronicles (2010) by Joss Ware Matched (2010) by Ally Condie Monsters of Men (2010) by Patrick Ness Mockingjay (2010) by Suzanne Collins Rondo (2010) by John Maher Delirium (2010) by Lauren Oliver Super Sad True Love Story (2010) by Gary Shteyngart The Scorch Trials (2010) by James Dashner The Prophecies (2011-2012 series) by Linda Hawley Wither (2011) by Lauren DeStefano Deus Ex Machina (2011) by Andrew Foster Altschul Dark Parties (2011) by Sara Grant Across The Universe (2011) by Beth Revis Shadow Children (1998-2006 series) by Margaret Peterson Haddix Divergent (2011 - Trilogy) by Veronica Roth Crossed (2011) by Ally Condie Shatter Me (2011 - Trilogy) by Tahereh Mafi The Always War (2011) by Margret Peterson Haddix XVI (2011) by Julia Karr The Limit(2010) by Kristen Landon The Death Cure (2011 - Trilogy) by James Dashner Blood Red Road (2011 - Trilogy) by Moira Young "Eve (2011 - Trilogy)" by Anna Carey Truth (2012) by Julia Karr Pandemonium (2012) by Lauren Oliver Legend (2011) by Marie Lu List of Dystopian Films Governmental/social A typical dystopia paints a picture of government or society attempting to exert control over free thought, authority, energy, freedom of information. Others focus on systematic discrimination and limitations based on a variety of factors - genetics, fertility, intelligence, and age being a few examples. 2081 (2009) Aachi & Ssipak (2006) Æon Flux (2005), adapted from the MTV animated series of the same name, created by Peter Chung. Alphaville (1965) Atlas Shrugged: Part I (2011) Babylon A.D. (2008) Battle Royale (2000), based on the novel and manga of the same name, and its sequel, Battle Royale II: Requiem (2003) Blade Runner (1982), based on the Philip K. Dick novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Book of Eli (2010) The Bothersome Man (2006) Brave New World (1998) Brazil (1985) The Breed (2001) Bunraku (2010) Children of Men (2006) Class of 1999 (1990) Code 46 (2003) Dark Metropolis (2010) Daybreakers (2010) Death Race 2000 (1975) and its prequel Death Race (2008) Demolition Man (1993) District 9 (2009) District 13 (2004) and its sequel District 13: Ultimatum (2009) Doomsday (2008) Dredd (2012) The End of Evangelion (1997) Escape from New York (1981) and its sequel Escape from L.A. (1996) Equilibrium (2002) Fahrenheit 451 (1966), based on the Ray Bradbury novel of the same name. FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions (2004) "Franklyn" (2008) Gattaca (1997) The Handmaid's Tale (1990) Harrison Bergeron (1995), a cable television movie adapted from the short story of the same name by Kurt Vonnegut The Hunger Games (2012), based on the Suzanne Collins novel of the same name. Idiocracy (2006) The Island (2005) In Time (2011) Judge Dredd (1995), based on the comic of the same name Kin-dza-dza! (1986) Land of the Blind (2006) Logan's Run (1976) The Matrix (series) (1999–2003) Megiddo: The Omega Code 2 (1999) Metropolis by Fritz Lang (1927) Minority Report (2002), based on Philip K. Dick's short story "Minority Report" Never Let Me Go (2010) Nineteen Eighty-Four, based on the George Orwell novel of the same name, filmed in 1956 by Michael Anderson and in 1984 by Michael Radford The Omega Man (1971) Privilege (1967) Punishment Park (1971) Revengers Tragedy (2003) The Running Man (1987), loosely adapted from Stephen King's novel of the same name A Scanner Darkly (2006), adapted from Philip K. Dick's novel of the same name Screamers (1995), based on the short story "Second Variety" by Philip K. Dick Serenity (2005), a continuation of the canceled Fox television series Firefly by Joss Whedon Silent Running by Douglas Trumball (1972) Sleeper (1973) Sleeping Dogs (1977) Soldier (1998) Southland Tales (2007) Soylent Green (1973), based on the Harry Harrison novel Make Room! Make Room! Strange Days (1995) THX 1138 (1971) The Secret (2016) The Trial (1962) Total Recall (2012) Turkey Shoot (1982) Ultraviolet (2006) V for Vendetta (2006), based on Alan Moore's graphic novel Welt am Draht (1973) Z.P.G. (1972) Alien controlled dystopias (both governmental and societal) Alien controlled dystopias are separate from general dystopias in that they are enacted on a people by an outside invader rather than members of the oppressed's own species. Battlefield Earth (film) a 2000 film adaptation of the novel, starring John Travolta. The Chronicles of Riddick (2004) Dark City (1998) Fantastic Planet (1973) Resiklo (2007) They Live (1988) adapted from Eight O'Clock in the Morning by Ray Nelson Titan A.E. (2000) Transmorphers (2007) Corporate based dystopias (nongovernmental) A corporate based dystopia is similar to a government/societal dystopia with the exception that the repressing power is a private company rather than a government. These stories generally include the motive of commercial profit instead of, or in addition to, the benefits of increased power and authority. Alien series Daybreakers The Fifth Element The Final Cut Fortress Gamer Hardware Highlander II: The Quickening I, Robot loosely adapted from Isaac Asimov's book The Island Johnny Mnemonic Metropia Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future No Escape Paranoia 1.0 Parts: The Clonus Horror Prayer of the Rollerboys Repo! The Genetic Opera Repo Men Resident Evil series by Paul W. S. Anderson RoboCop and its sequels RoboCop 2 and RoboCop 3 Rollerball (1975) and its remake Rollerball (2002) Shredder Orpheus (1990) Soylent Green Surrogates Tank Girl Tekken Total Recall and its television sequel Total Recall 2070 Organized Crime-Based Dystopias These films are essentially films about the Mafia or any other criminal organizations, such as the Triads, Yakuza, Russian Mafia, or Cosa Nostra, except that they all take place in the future. Looper (2012) Prison-Based Dystopias These dystopias are related to the governmental or corporate-based dystopias, but rather taking place inside a prison, dungeon, or similar prison-like environment. Running Man (1987) Gamer (2009) The Hunger Games (2012) Death Race (2008), and Death Race 2 (2010) Lockout (2012) Cyberpunk/techno Cyberpunk is a science fiction subset, characterized by a focus on "high tech and low life" where advanced technology itself (not AI) is dystopian. "Classic cyberpunk characters were marginalized, alienated loners who lived on the edge of society in generally dystopic futures where daily life was impacted by rapid technological change, an ubiquitous datasphere of computerized information, and invasive modification of the human body."[2] Aachi & Ssipak Akira Avalon Blade Runner eXistenZ Ghost in the Shell Johnny Mnemonic Metropolis by Osamu Tezuka Natural City Renaissance Sleep Dealer The Terminator Videodrome The Matrix Post-apocalyptic Post-apocalyptic storylines take place in the aftermath of a disaster - typically nuclear holocaust, war, plague - that justifies a civilization's turn towards dystopian like behaviors. Although not a requisite, most post-apocalyptic visions have a man-made cause. 9 (2009) 12 Monkeys (1995) 20 Years After (2008) 2019, After the Fall of New York (1983) 28 Days Later (2002) and its sequel 28 Weeks Later (2007) The Bed-Sitting Room (1969) A Boy and His Dog (1974) Blindness (2008) The Blood of Heroes (1989) The Book of Eli (2010) Carriers (2009) Casshern (2004) Cherry 2000 (1987) Children of Men (2006) Cyborg (1989) Def-Con 4 (1985) Delicatessen (1991) [Dystopia: 2013] (2012) Five (1951) Genesis II (1973) Hell Comes to Frogtown (1988) I Am Legend (2007) Le Dernier Combat (1983) Logan's Run (1976) The Last Man on Earth (1964) The Noah (1975) Mad Max (1979), The Road Warrior (1981) and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985) On The Beach (1959) and its remake On the Beach (2000) Origin: Spirits of the Past (Anime) (2006) Panic in Year Zero! (1962) Parasite (1982) Phase 7 (2011) Planet Earth (1974) The Postman (1997) The Quiet Earth (1985) Quintet (1979) Robot Holocaust (1986) The Road (2009) Rock & Rule (1983) Six-String Samurai (1998) Tank Girl (1995) Terminator Salvation (2009) Testament (1983) Things To Come (1936) Threads (1984) Time of the Wolf (2003) Titan A.E. (2000) The Ultimate Warrior (1975) Ultraviolet (2006) Ultra Warrior (1990) WALL-E (2008) Waterworld (1995) The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959) Zardoz (1974) Tomorrow, When the War Began (film) (2010) Damnation Alley (1977) Downstream (2010) Miscellaneous 2009 Lost Memories The City of Lost Children Encrypt Invasión Motorama Planet of the Apes (1968), Beneath the Planet of the Apes, Escape from the Planet of the Apes, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, Battle for the Planet of the Apes and the remake Planet of the Apes (2001) Pleasantville The Man Who Fell to Earth Sunshine Disputed Dystopias A Clockwork Orange (1971), adapted from Anthony Burgess's novel of the same name Dark Star (sci-fi satire film) List of Dystopian Comics BLAME! 20th Century Boys by Naoki Urasawa the second half of the story is set in Japan after a former cult leader known only as "Friend" controls the entire world. The Age of Apocalypse is an alternate reality of the X-Men. Attempting to kill the mutant Magneto in the past, before he can become a threat, the time-traveler Legion killed instead his own father, Charles Xavier, who took the shot to save his friend of that time. In this timeline, Magneto took the dream of Xavier for himself and started the X-Men, while the mutant Apocalypse created a dystopia where humans were destroyed. This dystopia would be erased from existence by a second time travel by Bishop, who prevented Legion from killing either Xavier or Magneto and so restored the usual Marvel continuity. Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, a non-continuity tale by Frank Miller, portrays an aged Batman returning to fight crime in a dystopian Gotham City. Akira, also set in a post-nuclear Tokyo, touches themes like youth alienation and government corruption. American Flagg is an American comic book series created by writer-artist Howard Chaykin, published by First Comics from 1983 to 1989. A science fiction series and political satire, it and was set in the U.S., particularly Chicago, Illinois, in the early 2030s. Appleseed by Masamune Shirow is a science fiction manga created by Masamune Shirow which merges elements of the cyberpunk and mecha genres with a heavy dosage of politics, philosophy, and sociology. Battle Angel Alita by Yukito Kishiro The recent events in the Marvel Universe following the "Civil War" storyline dealing with the Superhuman Registration Act could be seen as dystopian, especially "Dark Reign" in which the super villains are placed in positions of power. "Days of Future Past" is a dystopian future of the X-Men, in which the Sentinels, robots entrusted with protecting the human race from the mutants, take control of all human society. This dystopia is erased by a time-traveler Kitty Pryde, who goes back to the present and prevent the events that would lead to the dystopia. Eden: It's an Endless World by Hiroki Endo is set in a near-future world where a biological agent has wiped out approx. 15% of the world's population, while leaving a much larger number crippled and traumatized. Immediately following these events, political and religious upheaval drastically change the balance of power between nations and organized crime, with the two sometimes becoming indistinguishable. Fist of the North Star, also known as Hokuto no Ken, shows a post-nuclear society where people are threatened by gangs of bikers and violent martial art killers. Ghost in the Shell Wanted by Mark Millar depicts a world ruled by super villains. The Incal by Moebius and Alexandro Jodorowsky starts in a dystopian futuristic city populated largely by apathetic "TV junkies". Judge Dredd is set in a post-apocalyptic world dominated by megacities, like Mega-City One policed by ruthless lawmen called Judges. Marvel 2099 by various authors. The story spans several different books, taking place in a society ruled by a small group of Mega-corporations and a corrupt religion known as the Church of Thor. Marshal Law takes place in post-earthquake San Francisco (called San Futuro) where rival gangs of "super heroes" terrorize the city and are hunted by a government-sanctioned vigilante. Nikopol Trilogy by Enki Bilal, consisting of La Foire aux Immortels (The Carnival of Immortals), La Femme Piège (The Woman Trap) and Froid Équateur (Cold Equator) tells of dystopian future Paris ruled by fascist dictatorship. No. 6, based on the original novel series by Atsuko Asano. Ruins by Warren Ellis is the Marvel Universe in which the myriad experiments and accidents which led to the creation of superheroes in the mainstream world instead resulted in more realistic consequences: horrible deformities and painful deaths. The Walking Dead depicts the story of a group of people trying to survive in a world stricken by a zombie apocalypse. Influenced by George A. Romero's zombie movies and other works in zombie fiction. Transmetropolitan by Warren Ellis concerns a partially dystopian, postcyberpunk take on our world in some unspecified time from now. Nearly everyone lives in "The City," which is over-running with pollution and chaos. V for Vendetta by Alan Moore follows the exploits of the anarchist V and his struggle in a Britain ruled by a fascist party. Watchmen, also by Alan Moore, depicts the events leading to the destruction of New York City. The book is marked by a strong sense of alienation in a hostile society. Y: The Last Man where almost all male mammals in the world have died except for lead character Yorick and his male monkey Ampersand. Long running web comic Sluggy Freelance recently told a story of a dystopian alternate dimension where the entire Earth was changed into endless wastelands populated by hordes of mutants as a result of the Research and Development Wars, safe for the last bastion of humanity, 4U City. 4 U's stands for Universal Unified Ubiquitous Utopia. List of Dystopias in music Crime of the Century (1974) by the British band Supertramp depicted and evoked the personal, social and institutional causes and effects of alienation and mental illness in contemporary society. Time (1981) by ELO features tracks that may be considered dystopian or utopian depending on your point of view. OK Computer (1997) by the British band Radiohead. British band Pink Floyd and its film adaptation are considered by many to be the epitome of dystopian music. Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon (1973) and many of their other recordings also explore dystopian themes. The Pleasure Principle (1979) by Gary Numan, ex-leader of the Tubeway Army, continued his narratives of a robotic world in songs like Metal.