Love and War: Epic Romance in the Renaissance

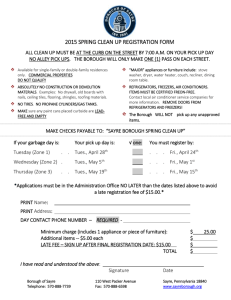

advertisement

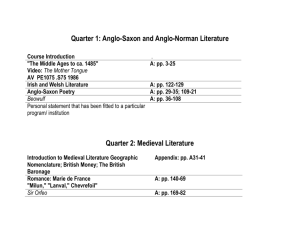

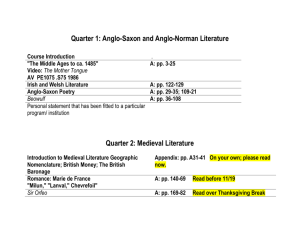

Love and War: Epic Romance in the Renaissance EL 482.01 Dr. Ethan Guagliardo Course Description “Blessed is he who has succeeded in learning the laws of nature’s working, has cast beneath his feet all fear and fate’s implacable decree, and the howl of insatiable Death. But happy, too, is he who knows the rural gods, Pan and aged Silvanus and the sisterhood of the Nymphs. Him no honours the people give can move, no purple worn by despots, no strife which leads brother to betray brother. Untroubled is he by . . . Rome’s policies spelling doom to kingdoms; if he has not felt pity for the poor, he has never envied the rich. He plucks the fruits which his boughs, which his willing fields, have freely borne; nor has he beheld the iron rigours of the law, the Forum’s madness, or the public archives. Other brave with oars seas unknown, dash upon the sword, or press their way into courts and the chambers of kings. One wreaks ruin on a city and its wretched homes, and all to drink from a jeweled cup and sleep on Tyrian purple; another hoards wealth and gloats over buried gold; one stares in admiration at the rostra; another, open-mouthed, is carried away by the applause of high and low which rolls again and again along the benches. They steep themselves in brothers’ blood and glory in it; they barter their sweet homes and hearths for exile and seek a country that lies beneath an alien sun.” – Virgil, Georgics, 2.490-512 Epic, at least since Virgil’s Aeneid, has always been the literary form of empire. Epics offer an expansive vision of the cosmos in which everything has its place—especially the barbarian, degenerate, and passionate “others” tamed by the epic poet’s authoritative voice, the voice of civilization, divinity, and reason. Yet on a second look, even Virgil seems to have had his doubts. In this class, we will examine the legacy of Virgilian doubt and counter-epic in the development of the early modern hybrid genre called “epic romance,” paying particular attention to the philosophical, religious, and social developments that helped shape the peculiar hybridity of Renaissance heirs to Virgil. We will also look at other genres—particularly tragedy—that responded to epic’s monological form, and concentrate on those supposed epic others—including femininity, affect, polytheism, pessimism, and anti-political sentiment—that both resist and seep into Renaissance epic. Primary readings include Lucretius’s De rerum natura, Virgil’s Aeneid, Marlowe’s Dido, Queen of Carthage, Spenser’s Faerie Queene, Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, and Milton’s Paradise Lost. Texts Virgil, Aeneid, trans. Robert Fagles (Penguin). ISBN: 0143105132. Milton, Paradise Lost, ed. William Kerrigan et al. (Modern Library preferred). Course packet. Assignments Weekly Assignments: In order to facilitate more fruitful class discussions, I will ask that you submit a one-page response paper every week, by Wednesday 10:00 AM, online. These response papers should concentrate on close-reading the language of a single passage. In Shakespeare, for instance, no more than three lines; in Spenser, no more than a single stanza. Nonetheless, you are invited and encouraged to connect your readings to the broader concerns and themes of the works. You may not miss any weeks. Exams: Short answer and essay questions. Final Paper/Exam: You may choose either to write a 10-page research paper due on the date of the final exam, or you may take a final exam. This paper’s topic will be crafted in consultation with me. Grade Distribution Participation Weekly Assignments Midterm Final Paper 20% 20% 25% 35% Other Course Policies Attendance: Attendance is mandatory. Participation is crucial to your success in this course. Students who do not attend at least 75% of classes will not be allowed to take the final exam or turn in a final paper. Any absences beyond three will lower your final grade for the course. Five or more unexcused absences will result in an F. Students who have not read assigned materials or have not come to class with their homework will be marked as absent and asked to leave class. I reserve the right to excuse absences in particular cases. Academic Honesty: All student work, whether graded or ungraded, must be his or her own. All sources consulted, whether in print or online, must be appropriately cited. If you are uncertain what constitutes plagiarism or academic dishonesty, please talk to me. Weekly Schedule Please note: All readings should be done by the day they are assigned. Week 1 Tues, Sept. 29th Introduction; Homer, “The Shield of Achilles,” from The Iliad [CP] Fri, Oct. 2nd Lucretius, De rerum natura, selections. Week 2 Tues, Oct. 6th Lucretius, De rerum natura, selections. Fri, Oct. 9th Virgil, Aeneid, Books 1-2. Week 3 Tues, Oct. 13th Virgil, Aeneid, Books 3-5.130. Fri, Oct. 16th Virgil, Aeneid, Books 6-7. Week 4 Tues, Oct. 20th Virgil, Aeneid, Books 8-12. Skim 9-11. Fri, Oct. 23rd Christopher Marlowe, Dido, Queen of Carthage, Acts 1-3. Week 5 Tues, Oct. 27th Christopher Marlowe, Dido, Queen of Carthage, Acts 4-5. Fri, Oct. 30th Spenser, Faerie Queene, Book 1, Cantos 1-2. Week 6 Tues, Nov. 3rd Spenser, Faerie Queene, Book 1, Cantos 9. Book 3, Proem and Canto 1. Fri, Nov. 6th Spenser, Faerie Queene, Book 3, Cantos 2-4. MIDTERM Week 7 Tues, Nov. 10th Spenser, Faerie Queene, Book 3, Cantos 5-6. Fri, Nov. 13th Spenser, Faerie Queene, Book 3, Cantos 11-12. Week 8 Tues, Nov. 17th Fri, Nov. 20th Spenser, Faerie Queene, Book 5, Proem and Cantos 1-2 (skim cantos 3-4.20 if you have time). Spenser, Faerie Queene, Book 5, Canto 4.21- canto 6.18; Canto 7 Week 9 Tues, Nov. 24th Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, Acts 1-3. Fri, Nov. 27th Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, Acts 4-5. Final Paper Proposal Due. Week 10 Tues, Dec. 1st Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, continued. Fri, Dec. 4th Milton, Paradise Lost, Book 1. Week 11 Tues, Dec. 8th Milton, Paradise Lost, Book 2-3.1-343. Fri, Dec. 11th Milton, Paradise Lost, Book 4. Week 12 Tues, Dec. 15th Milton, Paradise Lost, Books 5-6. First Draft of Final Paper Due. Fri, Dec. 19th Milton, Paradise Lost, Book 8. Week 13 Tues, Dec. 22nd Milton, Paradise Lost, Book 9. Fri, Dec. 25th Milton, Paradise Lost, Book 10; 12.574-end. Final Paper or Final Exam TBA Suggested secondary readings: Burrow, Colin. Epic Romance: Homer to Milton. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993. Campana, Joseph. The Pain of Reformation: Spenser, Vulnerability, and the Ethics of Masculinity. New York: Fordham University Press, 2012. Fallon, Stephen. Milton among the Philosophers. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991. Gregerson, Linda. The Reformation of the Subject: Spenser, Milton, and the English Protestant Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. Gross, Kenneth. Spenserian Poetics: Idolatry, Iconoclasm, and Magic. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985. Johnson, W. R. Darkness Visible: A Study of Virgil’s Aeneid. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976. Kahn, Victoria. Wayward Contracts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004. Kearney, James. The Incarnate text: Imagining the Book in Reformation England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009, chapter 2. Montrose, Louis. The Subject of Elizabeth: Authority, Gender and Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006. Nohrnberg, James. The Analogy of The Faerie Queene. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976. Norbrook, David. Writing the English Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ———. Poetry and Politics in the English Renaissance. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984. Parker, Patricia. Inescapable Romance: Studies in the Poetics of a Mode. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979. Picciotto, Joanna. Labors of Innocence in Early Modern England. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010. Quint, David. Epic and Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993. ———. Inside Paradise Lost. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014. Rogers, John. The Matter of Revolution: Science, Poetry, and Politics in the Age of Milton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996. Teskey, Gordon. Allegory and Violence. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996. Van Es, Bart. Spenser’s Forms of History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. Wofford, Susanne. The Choice of Achilles. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992. Yates, Frances A. Astraea: The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1975.