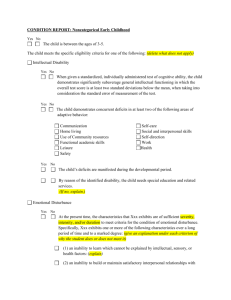

File - the Community-Based Service

advertisement