Interim Evaluation Report of the Bowel Screening

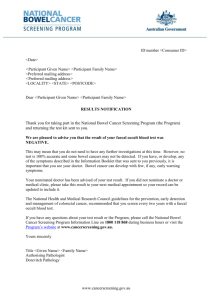

advertisement