Bertilak`s Castle, Saint Erkenwald`s St. Paul`s

advertisement

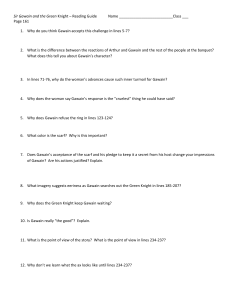

Nathan Garton, 2400235 Major Middle-English Texts. Course convener, Roger Nicholson. 6 November 2009. Bertilak’s Castle, Saint Erkenwald’s St. Paul’s, Jonah’s Bour, and Pearl’s Erbere: Sites of Transformation in Four Middle-English Alliterative Poems. 1 It has long been recognized that certain created spaces prescribe or influence the behaviour of those who occupy it.1 In this way one might assume certain manners and clothing at a fine Italian restaurant that would seem ridiculously out of place at McDonalds. The very language that we adopt to communicate the experience of ‘finery’ reflects this prescription, such that ‘attire’ and ‘deportment’ replace the ‘clothing’ and ‘manners’ of everyday experience. Fourteenth-century alliterative poetry seems to be especially interested in assembling particular architectural constructions that prescribe the crucial changes of their narrative. However, as we will see, these are not always ‘buildings’ in the conventional sense of brick and mortar; a poet is quite able to construct both a garden and a castle in order to fulfil similar textual functions. The rendering of architectural features, location, environment, perspective, sensory perceptions, mood, and manner, all contribute to an infusion of meaning into the textual space. Through an investigation of the textual architecture of Bertilak’s Castle, Saint Erkenwald’s St. Paul’s, Jonah’s Bour, and Pearl’s Erbere, I intend to demonstrate how these carefully constructed sites reflect and inform the transformations that occur within, and thus contribute to our reading of the poem as a whole. Bertilak’s castle. When Gawain prays on Christmas Eve for ‘sum herber Þer heZly I myZt here masse’ he has been a knight errant for close to two months.2 He is cold, uncomfortable, and lonely and laments his condition to Mary, pleading that ‘ho hym red to ryde, / wysse hym to sum wone’ (ll. 738-739). The poet masterfully evokes his hero’s gloomy mood as he rides into a wild, marshy forest of tangled hawthorn, old hoary oaks and ragged moss: a carefully painted scene of stark, eerie stillness, in which the birds on bare twigs ‘pitosly Þer piped for pyne of Þe colde’ (l. 747). In answer to his prayer for lodging in which to celebrate the birth of Christ he glimpses a castle shimmering through the trees. However, this is not just any castle, but ‘Þe comlokest Þat euer knyZt aZte’ (l. 767). As Gawain approaches, the reader senses the joy with which the knight’s starved senses savour its splendid architecture. Gawain’s gaze travels up from the deep moat in which the massive stone walls ‘wod … wonderly depe’, to the solid cornices and fortified battlements and on to the fine watch towers, and finally up to the high hall with its chalk-white chimneys and wondrously tall towers with intricate 1 Barbara Hanawalt, and Michal Kobialka, Medieval Practices of Space, University of Minnesota Press, 2000, p. x. 2 The feast in honour of Gawain’s departure is held on ‘al-hal-day’, November 1 (l. 536). and Gawain leaves the following morning. See also Harvey De Roo, ‘Undressing Lady Bertilak: Guilt and Denial in "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight"’, The Chaucer Review, Vol. 27, No. 3 (1993), pp. 312. 2 finials.3 Gawain cannot help observing that so many painted pinnacles scattered among the battlements ‘Þat pared out of papure purely hit semed’ (l. 802). (Indeed, for one so apparently bedraggled, a sight such as this would naturally lead to the thought of food.4)Thus Gawain takes in the castle from the bottom up, savouring the robust alongside the delicate with equal relish. The site of Gawain’s true test is constructed for the reader through a tightly controlled ocular perspective; what we see is both flavoured and limited by what Gawain himself sees.5 The visual apprehension at this point in the poem places an emphasis not on what is felt, or heard or smelled, but on what is seen; and what is seen, of course, repeatedly deceives.6 Indeed, shortly after we read that Gawain ‘rode in his prayere’ (l. 759), we discover that the castle is ‘pyched on a prayere’ (l. 768); a pun that disputes the appearance of permanence.7 Indeed, the castle’s apparent massiveness and well-appointed fortifications imply a solidity and stability that belies its unstable and magical appearance, as it ‘schemmered & schon ÞurZ Þe schyre okeZ’ (l. 772). The castle as a site of transformation thus presents the reader with a visually striking image of grandiose superfluity that is grounded in serious martial technology, which anticipates the elaborate game of courtly love and deception that is to take place within its walls; a game that ultimately decides Gawain’s fate in his impending encounter with the Green Knight. Gawain appreciates and savours the castle much like he does the ladies of that ‘won’ (l. 764). The sight of fine lodging is as welcome to him as that of fine company and Gawain appreciates the castle with the critical eye of someone who has had the opportunity to appreciate many castles. With a similarly experienced gaze he savours and compares the beauty of the young Lady with that of her older and uglier companion – a pairing of the robust with the delicate that mirrors that of the castle itself. The two ladies are vividly rendered through comparison as ‘vn-lyk on to loke’ (l. 950) and are, again like the castle, displayed for the reader through the controlled perspective of Gawain’s lingering eyes. Gawain seems at first to be stunned by the beauty of the young lady, ‘ 3 For a detailed examination of Bertilak’s Castle, see Robert Cockroft, ‘Castle Hautdesert: Portrait or patchwork?’ Neophilologus, Volume 62, Number 3, July, 1978, pp. 459-477. 4 Andrew and Waldron observe that Gawain compared the castle to paper cut-outs, which sometimes decorated food in fourteenth-century banquets, a practice that Chaucer’s Parson speaks disapprovingly of (CT, X, ll. 445), Malcolm Andrew and Ronald Waldron, eds., The Poems of the Pearl Manuscript, Fifth edition, University of Exeter, 2002, note to line 802, p. 238. See also Belshazzar’s feast in Cleanliness, l. 1408, and Betty Raddice, ed., Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Penguin, London, 1974, note to line 802, p.174. See also Cockroft, p. 474. 5 Crystal Downing, ‘Architecture as Synecdoche: A Poetics of Trace’, Pacific Coast Philology, Vol. 23, No. 1/2 (Nov., 1988), p. 485. 6 Downing, p. 487. 7 Ralph Elliot, ‘Landscape and Geography’, in A Companion to the Gawain-Poet, Derek Brewer and Jonathan Gibson, eds., Cambridge, 2002, p. 107. 3 Ho watZ fairest in felle, of flesche & or lyre & of compas & colour & costes of alle oÞer, & wener Þen Wenore, as Þ wyZe ÞoZt’ (ll. 943-945). The sequence in which Gawain then perceives the ladies as they approach him through the crowd of people is worth noting. He first notices their opposing abstract qualities, ‘Zonge’ and ‘ZolZe’ (l. 951); then their clothing, followed by the younger lady’s ‘brest & hir bryZt Þrote bare displayed’ (l. 955), whereas the body of her older companion is tightly muffled in veils. As they near him, the older leading the younger by the left hand, we only see the facial features of the former, whose eyes, nose and lips are ‘soure to se & sellyly blered’ (963). By comparison, ‘more lykker-wys on to lyk / WatZ Þat sho hade on lode’ (ll. 968-969). Thus we only ‘see’ the younger lady’s face through opposition to the older, and the reader is left to form their own impressions of her beauty. Thus Gawain’s eyes again travel from the bottom up, taking in clothing, breast, and throat before face. The lack of specificity in regards to the younger lady’s face and expression implies that it is not her eyes or expression or countenance that has captivated him, but her body. He sees her as a superlative specimen of courtly being and high society. And as Gawain himself has very recently been applauded for his own courtly virtuosity, her appearance is appreciated professionally as one with whom he will be able to ‘perform.’ And Gawain most clearly demonstrates a preoccupation to ‘perform’ the courtly game of love by the fact that he ensured the Lady’s continued access to his room. Had he been more concerned about the indecency of allowing the wife of his host apparently to fall in love with him he would have locked his door after her first visit. Thus it is Gawain’s obsession with his ‘cortaysye’ that ultimately gets him into trouble. The household is a place in which the Lord’s qualities of good management, control, and ‘knowing’ are repeatedly emphasised, and which Gawain himself recognises. 8 Yet our hero thinks that he can ‘fly under the radar’ with his secret encounters with the Lady: he uses what he sees as a genuine sexual attraction to him as an occasion to bolster his own courtly prowess and thus embarks on a performance that necessarily takes place behind closed doors.9 His astonishment and anger at himself in response to the lady’s brazen behaviour at the feast (l. 1660), indicates his awareness that things are getting out of hand, an understanding that is confirmed the following morning as the Lady appears in her most seductive negligee yet. However, while he had been playing his courtly game, behind which lay no inclination (at least initially) to have sex with her, it appears that she was playing a similar game, and had no such intensions either.10 And how he had enjoyed patronising 8 See especially SGGK, ll. 848-849, & the preparations for the first hunt, ll. 1126-1147. Harvey De Roo, ‘Undressing Lady Bertilak: Guilt and Denial in "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight"’ ‘The Chaucer Review, Vol. 27, No. 3 (1993), pp. 318. 10 De Roo, pp. 311-312. 9 4 her, with his ‘sleZteZ of ÞeweZ’ and ‘luf-talking’ (ll. 916 & 927). Gawain’s rejection of Bertilak’s benevolent offer to ‘yow wel acorde, / Þat watZ your enmy kene’ (ll. 2405-2406), thus smacks of wounded pride and embarrassment as he learns that all her flattery and praise was merely an elaborate ruse, which he fell for and nearly cost him his head. As a site of transformation, Bertilak’s castle establishes an emphasis on appearances. Its inherent dualities and ostentatious superfluity anticipates the façade of courtliness that Gawain and the Lady adopt toward one another; a course which eventually leads him to deviate from the principles of the pentangle under which he set out and place his trust in the green girdle. Gawain recognises that his courtliness failed him at Castle Hautdesert, and thus, his most applauded quality in tatters, he returns to Arthur’s court in shame. Saint Erkenwald’s St. Paul’s. The action of Saint Erkenwald opens in the midst of London’s conversion from pagan idolatry to Christianity. The poet recalls Saint Augustine’s recent missionary work as he ‘turnyd temples Þat tyme Þat temyd to Þe deuelle, / & clansyd hom in Cristes nome, & kyrkes hom callid’ (ll. 15-16). The reader learns that Augustine’s cleansing work seems to have been primarily a process of superficial transformation, of exchanging one image and name for another while leaving the structure itself intact. As we read of the religious environment of London being cosmetically transformed we notice that very little concern is given to the conversion of the heart and mind from paganism to ‘Christendame newe’. (l. 14) Saint Erkenwald, however, is concerned with the heart and the transformation that can only come from rebuilding from within. Thus the poem’s action is confined to a building that had formally been dedicated to a ‘maghty deuel’ (l. 27), and was being deconstructed in order that it could be reconstructed as a Christian centre of worship.11 The poem evokes and sustains a keen sense of place and the reader quickly gathers that this is a story that is specific to the experiences of London. In mid to late fourteenth-century London, St. Paul’s Cathedral was a popular site of religious and political dispute.12 Outspoken followers of heterodox thinking, such as the theology of John Wycliffe, would often assert their presence in the city by affixing anti-clerical manifestos to the cathedral door, and a common element of contention was the efficacy of sacramental transformations.13 In a scene rich with the sensations of boisterous humanity, the workers,14 as they ‘dalf so depe in-to Þe erthe’ (l. 45), discover the richly decorated 11 Casey Finch, ‘Introduction’ in, The Complete Works of the Pearl Poet, Casey Finch, ed. and trans., University of California, 1993. 12 Jennifer L. Sisk, ‘The Uneasy Orthodoxy of St. Erkenwald’, ELH , 74, (2007), p. 92. 13 Sisk, p. 92. 14 See T. McAlindon, ‘Hagiography into Art: A Study of "St. Erkenwald"’, Studies in Philology, Vol. 67, No. 4 (Oct., 1970), p. 481. 5 tomb of what appears to be a pagan king beneath the structure of what was to become St. Paul’s Cathedral. The presentation of St. Paul’s, a massively imposing structure in late fourteenth-century London, as being an unstable site of both architectural and spiritual conversion is thus a powerfully relevant image to contemporary readers. Furthermore, a poem in which the forsaken soul of a virtuous pagan attains heaven’s bliss through the miraculous performance of the sacrament of baptism specifically registers an awareness of, and response to, contemporary heterodox ideas.15 Thus, through specifically isolating the poem’s action within a tightly bounded location, the author demonstrates a concern to provide London with a spiritual as well as temporal history. This site of architectural and spiritual conversion, then, is the perfect location for the poet to explore Christianity as a transformative religion centred in salvation, and boldly asks the question of how this is to be obtained. As Christianity is literally being built into the geography of London the buried remnants of the past come to light, interrupting the process of construction and demanding attention before any further work can continue. This crisis reveals itself to be one of understanding, for before the workers lies a profound contradiction: either the miraculously preserved body before them is that of a great king who has quite melted out of memory – which means that he could not have been great enough to warrant record – or he is a saint who must have been a pagan – which means he cannot be a saint.16 Try as they might, the scholars of London cannot find ‘one cronicle of Þis kynge’ (l. 156) to illuminate his mysterious identity. When Saint Erkenwald arrives, however, he rebukes this mentality of self-reliance, ‘To seche Þe soothe at oure-selfe, Zee se Þer no bote’, (l. 170) pointing instead to reliance on God, ‘But glew we alle opon Godde, & his grace aske’ (l. 171).17 In a bold demonstration of this reliance, Erkenwald confronts the mystery before him and speaks to the corpse, ‘”Sithen we wot not qwo Þou art, witere vs Þi-selwen”’ (l. 185). To the astonishment of all those crowded about the chamber, the corpse answers and tells his sad story of being denied the bliss of heaven despite his virtuous life, and being condemned instead to state of eternal limbo in a miraculously preserved body. Moved with compassion, Erkenwald wishes that, Oure Lord lene . . . Þat Þou lyfe hades, by Goddes leue, as long as I kyZt lacche water, & cast ypon Þi faire cors, carpe Þes wordes, “I Folwe Þe in Þ Fader nome & his fre Childes & of Þe gracious Holy Goste”; – & not one grue lenger. 15 Sisk, p. 105. McAlindon, p. 485. 17 See also McAlindon, pp. 477-479. 16 6 As he sorrowfully utters these words, one of his tears happens to drop onto the face of the Judge, which inadvertently concludes the sacrament and the Judge’s soul promptly enters into paradise, leaving his body to crumble to dust before their eyes. Thus, within a contemporary context of heterodox scepticism, the poem expressly affirms an orthodox belief in the necessity and efficacy of baptism. Despite his virtuous life, the Judge’s unsaved state indicated that perfect adherence to common law was insufficient on its own to merit the rewards of heaven.18 However, it also poses an oblique challenge to this orthodoxy: the church’s power of the keys is certainly displayed in the poem, but the inadvertence of the baptism calls into question the degree of control that the church possesses. The narrative of salvation by baptism administered by a cleric asserts orthodoxy on the question of the church’s power to bind and loose, but the language describing Erkenwald’s performance of the sacrament hints at the heterodox view that this power belongs to God alone.19 As the miraculous transaction occurs in the heart of Saint Paul’s, amidst the public gaze of a jostling crowd, the poem thus creates a space for itself within the clamour of contemporary voices and explores the fundamental nature of Christianity’s transformative power in the context of total reliance on God. Jonah’s Bour. Unlike the two poems above, the constructed site of transformation in Patience occurs at the end of the poem. There is therefore a sense in which the Bour is a place to get to, and that the force of Jonah’s arrival is significant for our understanding of the poem as a whole, for it is in this shabby location, a very symbol of Jonah’s hastiness, that he is offered a lesson in the virtue of patience. What Jonah needs to be taught is that God is not just an apocalyptic Lord of judgement, but also the loving Yahweh working within history and who holds each individual and every society in his continuing care.20 The introductory sermonette on the beatitudes in which the poet stresses the relationship between the blessed who ‘han in hert pouerte’ (l. 13), and the blessed who ‘con her hert stere’ (l. 27), as both receiving the gift of ‘heuen-ryche’ (ll. 14 & 28). Furthermore, that the language of these two rewards is in the present tense, which indicates that those who are poor and those who are patient can receive ‘Þe heuen-ryche’ now.21 However, the poet elaborates that poverty endured without patience is merely torment that leads to anger (ll. 44-48) and thus resolves that ‘syn I am put to a poynt Þat Pouere hatte, / I schal me poruay Pacyence, & play me with boÞe’ (ll. 35- 18 Gordon Whatley, ‘Heathens and Saints: St. Erkenwald in Its Legendary Context ‘, Speculum, Vol. 61, No. 2 (Apr., 1986), pp. 332-333. 19 Sisk, p. 102. 20 Sandra Pierson, ‘"Patience" - Beyond Apocalypse’, Modern Philology, Vol. 83, No. 4, (May, 1986), p. 337. 21 Pierson, p. 341. 7 36). They are necessary ‘playmates’.22 The poet then provides the tale of Jonah as an exemplum to illustrate this point. Sulking in perverse indignation at the unexpected success of his preaching, Jonah defiantly waits for God to send his anger against the Ninevites in spite of their repentance.23 On a field overlooking the city ‘he busked hym a bour, Þe best Þat he myZt’ (l. 437). Apparently he did not expect to have to wait very long for he did not build himself a house, but a hovel out of plant material that he found lying around.24 Thus, we are to understand that Jonah’s ‘best Þat he myZt is a rough, flimsy and temporary structure of unstable and dissatisfied hastiness. In the context of the poet’s earlier discourse about the necessity for poverty and patience to be ‘play-feres’ (l. 45) we can interpret this situation as Jonah’s defining moment of poverty: he has absolutely nothing to show for his experiences in the fish and at Nineveh, except for a ruined cloak and a bitter heart; he has not encountered any financial gain, and his prophetic résumé now consists of forewarning a retributive destruction that did not come. And as he broods amidst his own shoddy handiwork, God demonstrates to him the bankruptcy of his self-centred perspective. Thus, God sends the woodbine to grow upon the emblem of Jonah’s impatience in the midst of his poverty. But this is no mere entangling ivy, but ‘Þe fairest bynde . . . Þat euer burne wyste . . . hit watZ brod at Þe boÞem, boZted on lofte, / Happed vpon ayÞer half, a hous as hit were’ (ll. 444-450). Jonah so delights in his upgraded accommodation that he lounges contentedly in its cool shade all day, laughing at his good fortune and having apparently lost all care for his recent grievances, ‘”Iwysse, a worÞloker won to welde I never keped”’ (l. 464). This period of pleasant shelter represents an extreme contrast to his experience in the fish: they are both ‘bours’ (ll. 276 & 437), one being intensely disgusting, the other pleasantly enjoyable, yet both equally supplied by God’s providence. However, God is not through with him yet, for that night, ‘God wayned a worme Þat wrot vpe Þe rote’ (l. 467) and before morning his precious woodbine was withered, exposing Jonah to the heat and the wind. Within the tirade of abuse against God that follows it becomes apparent that Jonah considered the woodbine to be of his own doing, ‘I keuvered me a cumfort Þat now is caZt fro me, / My wod-bynde so wlonk Þat wered my heued’ (ll. 485-486.) He would not have exhibited this much passion for his shabby bour, for he could easily have made himself another. He somehow felt entitled to the comfort of that woodbine, such that when it was taken away he accused God of injustice (l. 493). At this point God has Jonah right where he wants him to be, and 22 See Patience, l. 45. Priscilla Martin, ‘Allegory and Symbolism’, in A Companion to the Gawain-Poet, Derek Brewer and Jonathan Gibson, eds., Cambridge, 2002, p. 320. 24 Compare ‘busked’ here with SGGK, l. 509 where the poet uses the same word of birds building nests. 23 8 responds to this allegation by communicating his own divine sense of value. He points out that if Jonah felt such life-ending pain at the loss of a plant that he did not spend one hour to tend, how much more would God feel if, ‘I my trauayl schulde tyne of termes so longe, & type doun Zonder toun when hit turned were, Þe sor of such a swete place burde synk to my hert’ (ll. 505-507). He rebukes Jonah’s hastiness to deal out judgement saying that, ‘CouÞe I not Þole bot as Þou, Þer Þryued ful fewe’ (l. 521). God transformed Jonah’s bour in order to demonstrate that he is not concerned with temporary conveniences or inconveniences, but with a permanent change of heart, like that demonstrated by the Ninevites.25 Heaven-centred patience is required by his servants in the midst of both joy and hardship as God works out his wider transformative plan. Yet at the same time, Jonah himself had been at the centre of God’s attention. The story of Jonah begs the question of why God, in his omniscience, did not choose a more willing servant? The lesson that Jonah learns in the bour is that God is willing to summon a great storm, command a giant fish, miraculously grow a luxurious edenic oasis, direct a worm, call the warm West wind, and cause the sun to burn hot in order to get through to one stubborn heart. Pearl’s Erbere As the reader joins the mourning Jeweller in the opening stanzas of Pearl, he or she is forced to take notice of the location as being central to the situation of the poem. Through concatenating and punning on the word ‘spot’ (as being both a report of what the pearl is without – and thus an indication of its value to the Jeweller – and also a definition of location) the poet forces the erbere and the pearl’s most salient quality to inhabit the same word, indicating that the one needs to be understood in terms of the other. This invitation to comprehend the pearl in terms of the organic – as being somehow located within the luscious and colourful surroundings – extends also to the Jeweller, yet we quickly understand that the extent of his grief has not allowed him to fully accept it. He seems to perceive that the instability of the organic landscape ought to provide the consolation of the cyclical process of death, re-birth and due season, but he is so focussed on loss that his grief will not allow him to move to hope centred in resurrection.26 For although he admits that, ‘vch gresse mot grow of grayneZ dede; / No whete were elleZ to woneZ wonne’ (ll. 31-32), the cold desolation in his heart still grips him such that ‘My wreched wylle in wo ay wraZte’ (ll. 56). Thus the 25 26 Edward Vasta, ‘Denial in the Middle English "Patience"’, The Chaucer Review, Vol. 33, No. 1 (1998), p. 26-27. John Finlayson, ‘"Pearl": Landscape and Vision’, Studies in Philology, Vol. 71, No. 3 (Jul., 1974), p. 319. 9 organic location of the dreamer’s distress defines his eventual transformation as finding reassurance in an acceptance of physical death as a necessity for spiritual life. The jeweller is a man who is controlled by his senses and dominated by strong primary impulses.27 The erbere, insofar as it is a production of the narrator’s senses, is also a reflection of his emotional state of being.28 In the first stanza he mentions the grass through which his pearl ‘yot’ (l. 10); the second stanza tells of the garden’s stillness; in the third he mentions the presence of many colourful spices, flower and fruit plants and how they ‘schyneZ ful schyr again Þe sunne’ (l. 28), but it is not until the fourth that we learn precisely what they are, ‘Gilofre, gyngure and gromylyoun, / A pyonys powdered ay bytwene’ (ll. 43-44) and of the fair scents wafting through the peaceful air. The erratic way in which we encounter the garden’s beautiful environment suggests not overall disorderliness, but of a natural order that the narrator does not yet recognise.29 He seems to attribute the garden’s beauty and tranquillity to the pearl’s presence, but remains woefully unable to take the next step of finding solace in the spiritual implications. The Dreamer tells us that this occasion of his visit is ‘In Augoste in a hyZ seysoun’ (l. 39). Elizabeth Petroff argues that this could mean the Assumption of the Virgin, which was celebrated on August 15, and which can be understood as a celebration of continuity between heaven and earth, the natural and the supernatural.30 In addition, the Dreamer informs us that this was at a time ‘Quen corne is coruen with crokeZ kene’ (l. 40). The specific timing of the situation thus also hints at themes of due season and spiritual perfection that also fail to penetrate the heart of one who is so consumed with loss. All these components combine to produce an environment in which the dreamer clashes with his location – his spiritual state is at odds with everything around him producing an acute tension that desperately needs to be resolved. This essentially is the ‘problem’ of the poem: in the Dreamer’s heart the garden continues to remain a place of death because he has buried his treasure there. Yet, by failing to come to terms with the pearl’s immortality, the Dreamer has underestimated her absolute value.31 He is indeed no ‘joyful jeweller’. He must transform his comprehension of the pearl’s value from being something that is lost, to something that is truly perfected. Therefore, the only way in which he is able to transform his earthly thinking is to 27 Finlayson, p. 328. Elizabeth Petroff, ‘Landscape in "Pearl": The Transformation of Nature’, The Chaucer Review, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Fall, 1981), p. 185. 29 Petroff, p. 185. 30 Petroff, p. 181. 31 A. C. Spearing, ‘Symbolic and Dramatic Development in "Pearl"’, Modern Philology, Vol. 60, No. 1 (Aug., 1962), p. 4. 28 10 experience a vision that takes him outside of that spot and into an encounter that directly confronts him with its implicit symbolic meanings.32 When the dreamer encounters the Pearl Maiden, she is very careful not to encourage or re-ignite any emotional connection. This is to be no miraculous reunion, for his consolation is not to be found in the recovery of a beloved daughter, as if death had not after all occurred or had no significance, but in the knowledge that she is redeemed and saved.33 As a queen of Heaven, her love is now for God; she is not pining for her earthly father, but completely satisfied in heavenly relationship with her divine ‘husband’. And she encourages her father to take his heart away from longing for what was always transitory, For Þat Þou lesteZ watZ bot a rose Þat flowred and fayled as kynde hyt gef. Now ÞurZ kynde of Þe kyste Þat hyt con close To a perle of prys hit is put in pref. (ll. 268-272) and place it in hope for the eternal, I rede Þe forsake Þe worlde wode And porchace Þy perle maskelles. (ll. 743-744) Yet he remains caught up in his earthly understanding of value and cannot comprehend the splendid inheritance that was given to one who had, … lyfed not two Zer in oure Þede; Þou cowÞeZ neuer God nauÞer plese ne pray, Ne neuer nawÞer Pater ne Crede; And quen mad on Þe first day! (ll. 483-486) The maiden responds by telling the parable of the workers in the vineyard (Matt 20: 1-16) to illustrate the divine sense of valuation as being quite different from earthly preoccupation with merit. However, being a man of senses, the dreamer has to see it for himself. It is not until he has witnessed something of the joy of the New Jerusalem, and experienced the futility of his earthly demands (l. 1200) that he is able to find the consolation that he needs. Having thus come through these phases of revelation, he is returned abruptly to the garden with a transformed understanding of that location, finally able to see the consolation it had to offer, and finally understanding that his heart’s treasure is not to be found within that spot, but in heaven.34 32 Petroff, p. 186. Gordon, E. V., ed., ‘Introduction’ in Pearl, Oxford University Press, 1966, p. xviii. 34 Matt 6:19-21, “Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasure in heaven, where moth and rust do not destroy, and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” New International Translation. 33 11 The textual architecture of Bertilak’s Castle, Saint Erkenwald’s St. Paul’s, Jonah’s Bour, and Pearl’s Erbere, all hint at how we are to read the transformations that take place within. Gawain’s courtesy comes under intense visual scrutiny in the grandiose dualities of castle Hautdesert; the miraculous baptism of the pagan Judge occurs during the construction of a contemporary site of sacramental scepticism; Jonah is offered the opportunity to transform his self-centred perspective with heavenly patience within an emblem of dissatisfied hastiness and poverty; and the joyless Jeweller comes to accept and find comfort in physical death as being necessary for spiritual perfection in an organic environment filled with reminders of this very principle. These carefully constructed sites are loaded with qualities that convey a customised symbolic freight designed fit the transformations of the narrative. These places matter to the text: after all, a test of Gawain’s courtesy would be rather bizarre if it occurred in a hovel such as Jonah’s; likewise, the contemporary resonances of St. Erkenwald’s inadvertent baptism would certainly lose their potency if this event occurred in a garden. Thus the poet is able to speak to us through the construction of space, for in the same way that a ghost story needs a haunted house, a transformation needs an unstable structure. 12 Bibliography Editions Andrew, Malcolm and Ronald Waldron, eds., The Poems of the Pearl Manuscript, Fifth edition, University of Exeter, 2002. Andrew, Malcolm and Ronald Waldron, eds., Pearl, Cleanliness, Patience, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A Prose Translation, University of Exeter Press, 2007. Bateson, Hartley, ed., Patience: A West Midland Poem of the Fourteenth Century, Second Edition, Manchester University Press, 1918. Gollancz, Israel, ed., Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, London, E.E.T.S., 1940. Gordon, E. V., ed., Pearl, Oxford University Press, 1966. Raddice, Betty, ed., Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Penguin, London, 1974. Other Primary Sources Chaucer, Geoffrey, The Canterbury Tales, Everyman Edition, A. C. Cawley ed., London 1996. Also available at http://www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/ November 20009. Secondary Sources Cockroft, Robert, ‘Castle Hautdesert: Portrait or patchwork?’ Neophilologus, Volume 62, Number 3, July, 1978, pp. 459-477. De Roo, Harvey, ‘Undressing Lady Bertilak: Guilt and Denial in "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight"’, The Chaucer Review, Vol. 27, No. 3 (1993), pp. 305-324. Downing, Crystal, ‘Architecture as Synecdoche: A Poetics of Trace’, Pacific Coast Philology, Vol. 23, No. 1/2 (Nov., 1988), pp. 13-21. Elliot, Ralph, ‘Landscape and Geography’, in A Companion to the Gawain-Poet, Derek Brewer and Jonathan Gibson, eds., Cambridge, 2002. Finch, Casey, ‘Introduction’ in, The Complete Works of the Pearl Poet, Casey Finch, ed. and trans., University of Caifornia, 1993. Finlayson, John, ‘"Pearl": Landscape and Vision’, Studies in Philology, Vol. 71, No. 3 (Jul., 1974), pp. 314-343. Gordon, E. V., ed., ‘Introduction’ in Pearl, Oxford University Press, 1966, pp. ix-lx. Hanawalt, Barbara, and Michal Kobialka, eds., Medieval Practices of Space, University of Minnesota Press, 2000. 13 McAlindon, T., ‘Hagiography into Art: A Study of "St. Erkenwald"’, Studies in Philology, Vol. 67, No. 4 (Oct., 1970), pp. 472-494. Nissé, Ruth, ‘A Coroun Ful Riche: The Rule of History in "St. Erkenwald"’, ELH, Vol. 65, No. 2 (Summer, 1998), pp. 277-295. Petroff, Elizabeth, ‘Landscape in "Pearl": The Transformation of Nature’, The Chaucer Review, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Fall, 1981), pp. 181-193. Pierson, Sandra, ‘"Patience" - Beyond Apocalypse’, Modern Philology, Vol. 83, No. 4, (May, 1986), pp. 337-348. Priscilla Martin, ‘Allegory and Symbolism’, in A Companion to the Gawain-Poet, Derek Brewer and Jonathan Gibson, eds., Cambridge, 2002, pp. 315-328. Sisk, Jennifer L., ‘The Uneasy Orthodoxy of St. Erkenwald’, ELH, 74, (2007), pp. 89–115. Spearing, A. C., ‘Symbolic and Dramatic Development in "Pearl"’, Modern Philology, Vol. 60, No. 1 (Aug., 1962), pp. 1-12. Whatley, Gordon, ‘Heathens and Saints: St. Erkenwald in Its Legendary Context ‘, Speculum, Vol. 61, No. 2 (Apr., 1986), pp. 330-363. Vasta, Edward, ‘Denial in the Middle English "Patience"’, The Chaucer Review, Vol. 33, No. 1 (1998), pp. 1-30. 14