Implementation of Grand Rounds Novice

advertisement

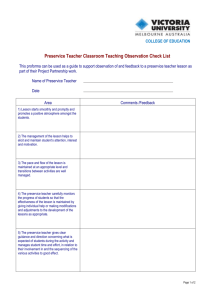

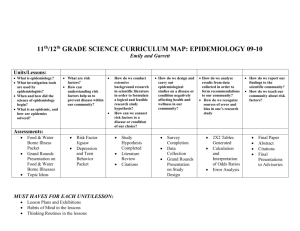

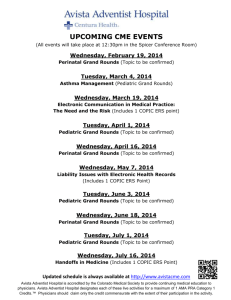

1 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Implementation of the Grand Rounds Model in Teacher Education: Guiding Classroom Observations for Novice Preservice Teachers 2 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Abstract This study examined the use of a Video Grand Rounds model in which elementary preservice teachers participated in a structured video observation approach. Preservice teachers enrolled in an early experiences course participated in the experimental design. Data were gathered through student reflections, final exam responses, and transcriptions of debriefing sessions. Analysis of the data followed a qualitative approach using an emergent coding system. Findings across both the treatment and control groups were very similar. Key refinements to the intervention model include 1) identifying videos that are more reflective of authentic classroom observations, 2) refining the observation protocol to emphasize the specific video classroom environment, and 3) broadening the use of the observation protocol as a framework for debriefing sessions. The model examined here should be considered one that is very generic in form and is applicable to a variety of classroom settings across the K-5 grade levels. 3 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Implementation of the Grand Rounds Model in Teacher Education: Guiding Classroom Observations for Novice Preservice Teachers The use of video clips in the teaching profession has been very effective over time in providing teachers and preservice teachers with feedback on their own instruction. Building on the powerfulness of using classroom instruction as a tool for learning, during the 2012-2013 academic year, a Video Grand Rounds model was piloted where video clips of experienced elementary (K-5) teachers teaching in their classrooms were used for observations by preservice teachers in conjunction with a structured classroom observation protocol instrument and support of a faculty member. The purpose of this model is to help preservice teachers focus their classroom observations on elements of quality instruction. The concept for this Video Grand Rounds model was borrowed from the use of Medical Grand Rounds which has been used for the training of doctors since the late 19th century (Herbert & Wright, 2003). Instead of discussing a patient’s case as in the medical model, video clips of classroom teaching are used as cases to discuss elements of quality instruction, as well as elements of a positive learning environment. This Video Grand Rounds model introduces a conceptual framework for preservice teacher observations using video clips to provide these preservice teachers with a standardized and efficient means for guiding classroom 4 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS observation experiences. The grand rounds process includes having preservice teachers view a series of lesson videos, complete structured observation protocols, and debrief with a faculty member following each video observation. This process allows preservice teachers the opportunity to view a classroom from a teacher’s perspective rather than the student perspective they have experienced for their 13 plus years of education. Prior to entering undergraduate teacher education programs, a national accreditation requirement is for preservice teachers to enroll in a preliminary clinical experience course in which they spend a specified number of hours (e.g., 16 hours) in unstructured school observations in combination with guided classroom discussions led by faculty. Considering the possible role of such classes in teacher education, two elements are important: 1) to provide prospective preservice teachers with exposure to representative K-5 classroom settings in a manner that helps them determine if obtaining a teaching degree fits their future goals, and, 2) to provide preservice teachers with a sound conceptual foundation for their future study in the teacher education program. Review of the Literature The notion of Pedagogies of Practice (Grossman et al., 2009) was used to provide the theoretical perspective for this research. Pedagogies of Practice is a framework designed to specifically explain the teaching of practice in 5 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS professional education programs. Grossman and her colleagues identified three key components for understanding the pedagogies of practice in programs of professional education. These include representations, decomposition, and approximations of practice. Representation of practice alludes to the ways practice is represented and made visible to the novice - in the case of this research - to the preservice teacher. Decomposition refers to the breaking down of that visible practice into parts so that the novice may learn the practice. Finally, approximation refers to the novice’s opportunities to begin to engage in professional practices as a novice. This research focuses on the first two components of pedagogies of practice, representation and decomposition, through the use of video cases as a representation of teaching in order to study and learn about teaching. Preservice teachers spend considerable time in their university classroom learning about theories and principles related to the learning of their future students. In order to help the preservice teachers apply those theories and principles to actual practice, or to the understanding of practice in the classroom, field experiences of various natures have been hallmarks of preservice teacher education programs. Often, these field experiences begin with observations of actual classrooms early in the preservice teacher program. One serious drawback of these early observations is that the preservice teacher tends to still view the classroom from a student viewpoint rather than a 6 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS teacher viewpoint. Several studies have noted that preservice teachers must be guided through these early observation experiences to learn to see the classroom from a teacher’s perspective and to help them connect their university coursework with its application in the classroom (Author, 2009; Hult & Edens, 2001; McDevitt, 1996). One method that has been used in teacher education to address the preservice teacher’s need for guidance and structure in learning observational skills is the use of the case method. The case method was rooted in the concept of the situative perspective in teacher education (Putnam & Borko, 2000) which is a theory adapted for teacher education from the Theory of Situated Cognition (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989) and asserts that learning must occur within authentic contexts. The case method allows preservice teachers to be involved in authentic experiences and has been used in law, business, and medical schools for years. As it has become more difficult for institutions of higher education to find physical placements for the many preservice teachers they instruct, the case method has gained ground in teacher education as well. One of the more common ways researchers have recently studied the use of the case method is through the use of video clips to help focus preservice teachers on important aspects of teaching and classrooms (Brophy, 2004; Author, 2009; Marsh, Mithcell & Adamczyk, 2010). The use of video allows the teaching 7 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS process to be slowed down, to be discussed, and to be reflected upon in ways that aren’t possible during a face to face observation (Santagata, Zannoni, & Stigler, 2007). Sonmez and Hakverdi (2012) used videos as an instructional tool as part of their science teacher education program to provide what they called, “…a shared common experience in a controlled environment…” with a goal of helping them analyze strengths and weaknesses in a lesson. They found that their preservice teachers showed progress in their ability to identify salient aspects of the teaching process. Likewise, Santagata, Zannoni, and Stigler (2007) used videos for two years in a teacher education program to teach lesson analysis and found that, by providing a specific framework to guide their observations, the preservice teachers’ comments of the video moved from simple descriptions of the teaching event to describing the effects the instruction was having on the learner. The literature is consistent in its findings that structure and guidance are necessary for early teaching observations by preservice teachers and that the use of video is an effective method for providing that guidance (Brophy, 2004; Author, 2009; Hult & Edens, 2001; Marsh, Mithcell & Adamczyk, 2010; McDevitt, 1996; Santagata, Zannoni, & Stigler, 2007; Star & Strickland, 2007). How, then, can what is known about the importance of structure and guidance in early field experiences and what is known about the use of video in preservice teacher education courses be combined and enacted most effectively in university teacher preparation programs to aid the learning of observational skills? 8 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Instructional Systems Design (ISD) offers one such avenue in addressing this need (Dick, Cary & Cary, 2011). ISD models present frameworks for the design of instruction and for establishing the effectiveness of the instruction developed. The observation categories discussed below primarily reflect elements addressed in ISD models as requirements that are necessary, but not sufficient for, sound instruction. Ideally, a conceptual framework for classroom observations by students who are novice observers must meet several methodological requirements. First, the requirements for observing, and then conceptually categorizing what has been observed, must be within the cognitive/experiential capacity of the participating students. Second, as much as is possible, the conceptual framework for the observation task(s) should focus on systemic classroom dynamics that are extensible for use in an increasingly detailed fashion in the teacher education program itself. Third, each category of classroom dynamics observed should be explainable by instructors in the form of specific procedures that teachers could apply to accomplish the observed outcomes in a manner that represents effective classroom practice. Overall, these standards potentially allow the introductory clinical experiences to serve as a general introduction to important aspects of teaching practices that provide an initial conceptual framework for students beginning a teacher education program. 9 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS The ISD model provides the framework for incorporating the theoretical perspective from which this research was designed. It allows for offering representations of teaching and then having the preservice teacher study and learn about teaching through structured observation tasks, thus incorporating the decomposition practice as well. The particular instructional strategy chosen to fill in the structure of this model is described next. Grand Rounds is an instructional strategy that is being used in teacher education as an idea that was borrowed from the medical profession (Thompson, S., & Cooner, D.D., 2001) and, one that addresses the key components of ISD. In this strategy, preservice teachers observe master teachers and participate in a debriefing session after the instruction. This mirrors the process used by medical interns in teaching hospitals where an intern works with a doctor and they discuss patients, conditions, and treatment plans on a case by case basis, thus helping the intern learn the practice of medicine. The idea of an instructional rounds approach to teacher education was first posited by Del Prete (1997) and included the three components of orientation, observation, and reflection. Since that time, this strategy has been adapted and used in various areas of teacher education. It has been most currently used as a model of professional development for student interns at the University of South Carolina in a live observation format (Zenger, 2003). 10 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS The use of video as a strategy for observational training in teacher education programs meets multiple criteria for effective teacher education. It honors the importance of keeping the preservice teachers’ learning situated within authentic contexts (Putnam & Borko, 2000), while also providing an avenue for their learning to be structured, guided, and discussed by and with their university professor. Furthermore, it allows for the representation and decomposition of teaching practices that Grossman et al (2009) defined as necessary in the teaching of practice. This research, framed by the theory of Pedagogies of Practice, seeks to combine what is known about how to guide and structure observations for preservice teachers with the key components of effective novice observations under Instructional Systems Design. Using the Grand Rounds approach, this combination is achieved through the use of video clips as a representation of teaching, and through the decomposition of the teaching and learning viewed in those video clips, thus extending the work in the area of instructional grand rounds as most of the research done has involved live observations. Method Participants 11 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS All preservice teachers in this research were enrolled in a one credit early experience elementary education course requiring 16 hours of classroom observation. Preservice teachers enrolled in the early experience course were limited in their prior knowledge of both curricular context and instructional strategies. During the 2012-2013 academic year, 294 sophomore level preservice teachers participated in the Video Grand Rounds model study. One hundred ninety of those preservice teachers were in the control group and 104 preservice teachers were enrolled in the treatment group. Procedures All preservice teachers enrolled in the early experience course were assigned to either a treatment or control group. Preservice teachers enrolled in the treatment group used a structured observation protocol as a guide for viewing video clips prior to engaging in school-based classroom observations. Preservice teachers enrolled in the control group engaged only in classroom observations without the use of observation protocols or debriefing sessions. The Video Grand Rounds group (the treatment group) participated in observations, protocol completion and teacher-led debriefing discussions about what was observed in the video clips. In order to complete the 16 required hours of observations, the preservice teachers in the treatment groups observed four videos of classroom instruction, completed an observation protocol in conjunction with each observation, and participated in classroom debriefing sessions to meet 12 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS 12 of the 16 required observation hours. They then completed an additional four hours of school-based classroom observations and completed another observation protocol to fulfill the remaining requirement. The figure below outlines the classroom observation process for the Video Grand Rounds model in the early experience course. As shown in Figure 1, the use of representative classroom video clips would precede the sequence of classroom observation and follow-up discussion. Data Collection Documents collected throughout the study included: 1) observation protocol forms detailing the preservice teachers’ observation experiences 2) transcriptions of recorded debriefing discussions about the observation experiences; 3) an open-ended description of a novel classroom instructional video as a component of their final exam, and; 4) a reflective essay about the overall practicum experience focused on what they learned from their observations. Data Analysis Analysis of the data followed a qualitative approach involving the use of the constant comparative method (Glaser & Straus, 1967) using an emergent coding system. The initial step of data analysis involved a preliminary examination of the data sets in which a checklist of initial categories was created. 13 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS This checklist of categories was then used in order to code the contents of each data set. Once the responses were coded, five major categories emerged from the data. The preservice teachers’ individual comments were then assigned to appropriate categories using the coding scheme that was developed in the first round of analysis. Finally, the final round of analysis involved the use of descriptive statistics in order to provide an overall summary of the findings and the observations made from the qualitative description of the data. In qualitative studies, the concept of triangulation replaces the notions of reliability and validity to ensure viable results (Creswell , 2013). Triangulation of the data was achieved through the use of methodological triangulation. Multiple sources of data were collected and analyzed. Data sources included student reflections, exams, and transcribed debriefing sessions. Additionally, findings from each data set were used to compare to each other to locate either patterns or inconsistencies within the data as the research questions were answered. Data were analyzed in order to answer the following research questions: 1) How does the use of a structured observation approach using observation protocols and debriefing sessions affect the self-reported observations of early experience preservice teachers observing a video, and, 2) How does the use of a structured observation approach using observation protocols and debriefing 14 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS sessions affect the self-reported learning experiences of early experience preservice teachers observing in a classroom? The data from the exams and debriefing sessions were used to answer the first research question related to the observations preservice teachers made after observing a video clip. The data from the final reflections were used to answer the second research question related to their self-reported learning experiences. Findings Exams Results indicate that the preservice teachers’ observations on their exams focused on five main categories: 1) the teacher in which observations included personal or affective comments about the teacher and/ or appraisal of the teacher’s work; 2) teaching strategies in which lesson steps, instructional strategies, or other things the teacher did throughout the lesson were observed; 3) classroom management strategies involving teacher implemented strategies used to manage the classroom; 4) the students which included students’ affective reactions to instruction, their behaviors , diverse needs; and, 5) student/teacher interactions which included observations related to respect between the students or between the students and their teacher, cooperation, and other comments related to the classroom environment. 15 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Analysis of the exams revealed that, overall, there were no differences between the treatment and control groups across the academic year, 2012-2013, related to what each group noticed and what they noticed the most. Each group made the same types of observations regardless of treatment. For example, both groups noticed teaching strategies more than anything else they observed, and they made observations about the teacher the least. The only notable difference was that a higher percentage of students in the control group noticed teaching strategies (+6 %) more often than those in the treatment group. This increase in observations of teaching strategies by the control group coincided with a reduction in the amount of teacher/student interactions observed by the control group. The treatment group noticed teacher/student interactions and other factors associated with the learning environment at a higher incidence (+4%) than the control group and they made observations about the teacher (+3%) more than the control group. Observations related to classroom management were identical across the control and treatment groups, as were observations about students (an increase of only 1% for the control group). See Table 1. Each of these major categories was further subdivided into smaller categories the preservice teachers tended to notice the most. See Table 2. There were several subcategories in which differences in rates of observations were greater than 10% between the treatment and control groups. Overall, the control group reported higher observations in the categories of instructional strategies, 16 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS use of visuals, student diversity and peer interactions. The treatment group reported higher observations in the categories of directions, physical arrangement of the classroom, management techniques, students’ behavior, and respect. For example, within the teaching strategies category, the control group noticed content methods and instructional strategies more than the treatment group (+18%), as well as teacher-given directions and stated objectives (+11%) and the use of visuals and music to teach content (14%). In the category of classroom management, the treatment group noticed the physical arrangement of the room more than the control group (+27%), as well as behavior management techniques (+90%). No major differences existed between the groups in observations related to the teacher; however, differences in rates of observations related to the students were found between the two groups. The treatment group noticed the students’ behavior at an increased rate over the control group (+18%), but the control group notice the diversity among the students more than the treatment group (+25%). Finally, in the last category of student/teacher interactions, the control group noticed student and peer to peer interactions more than the treatment group (+12%), while the treatment group noticed issues related to classroom environment such as trust and respectful relationships more than the control group (+44%). 17 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Reflections In the reflections, two additional themes emerged from the data in addition to the ones that emerged from the exams. These new categories were Self and Unexpected Events. In the reflections, the preservice teachers were asked to reflect on their learning experiences overall, so they naturally spoke most often of themselves and what they learned. The Self category included comments related to the things the preservice teachers felt they learned; things they need to work on; things they got to do in the classroom; ideas for their future classroom; learning to see the classroom from a teacher viewpoint; affective feelings about teaching including being excited, loving it, helping kids, impacting the children in some way; and confirming their decision to teach. The comments mentioned the most, by far, in self-reported learning experiences were that the face to face observations confirmed their decision to choose teaching as a career, with 45% of the preservice teachers mentioning this. Additionally, 40% of the preservice teachers mentioned they gained ideas for their future classroom. Because they were also discussing their experiences in a physical classroom as opposed to just a video case, as in the exams, a category of unexpected events emerged including the unexpected happenings that occur daily in an elementary school classroom. This category of unexpected events included such things as fights breaking out between students, children becoming ill, fire drills, lesson plans that must be changed due to unexpected events in the 18 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS classroom, and things the preservice teachers felt they observed that couldn’t be learned in a college classroom. Finally, the five categories that emerged from the exam data set also emerged from the reflections. The Teacher category included comments related to affective traits necessary to be a teacher such as calm, patient, flexible, and loving and professional traits required to be a teacher such as being organized and being a leader. The student category again included comments related to student behavior and diverse needs; the classroom management category again contained comments related to the physical arrangement of the classroom, transitions, and management strategies for student behavior; and, again, the interaction category included observations of respectful relationships and types of interactions between students and students and students and teachers. And, finally, the strategies category included comments related to questioning, use of grouping, statement of objectives, and contents and methods observed. Overall, there were no differences between the treatment and control groups related to what each group noticed and what they noticed the most. Each group made the same types of observations at approximately the same rate of observation regardless of treatment. For example, both groups discussed things related to themselves the most in their reflections, and they made observations about the teachers, interactions, and unexpected events the least. See Table 3. 19 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Debriefing Sessions Table 4 below indicates points of discussion in each debriefing session and includes comments of observations made by the students, as well as comments from the professors asking the students about the videos. It is of interest to note that these points of discussion align with the observations the students made in their exams. From these findings, it appears that what the professor draws the preservice teachers’ attention to during the guided video observation may impact the observations they make when they independently view a lesson. For example, Professor A’s discussions included many more comments about positive teacher/student relationships, respect, classroom environment, etc. and this is reflected in the preservice teachers’ observation comments. See Table 4. In the categories and subcategories charts for both the exams and the reflections, the data show that the preservice teachers in the treatment groups made more observations related to the classroom environment and interactions than those in the control group. In the exam analysis, the data show a 4% higher rate of observations related to classroom environment and interactions. In the reflections, the response rate is only 2% higher than the control group; however, this is one of only two categories in which the treatment group made a higher rate of response with Teacher being the other category with a rate of +4% over the 20 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS control group. Additionally, within the category of interactions, 72% of the treatment group noted observations related to respectful relationships and trust, while only 28% of the control group did. Since Professor A taught almost all the treatment groups, those points of discussions may have impacted the preservice teachers’ independent observations later. Discussion and Conclusions Findings across both the treatment and control groups were very similar. A possible reason for this may be the need for a more tailored observation and debriefing guide in the future that focuses on specific aspects of the video lesson to which the preservice teachers’ attention should be drawn during the guided observations. It appears from the findings that the discussions led by the professor in the debriefing session may have impacted the preservice teachers’ later observations; therefore, it may be likely that a structured observation and debriefing guide specifically aligned with the video in which the preservice teachers are told to observe for specific lesson components, and then guided in viewing those components, would similarly focus their later independent observations. Furthermore, repeated viewings of the same video clip in which the preservice teachers’ attention is drawn to various aspects of the lesson each time may also create more of an impact. For example, the video may be viewed the 21 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS first time for classroom management strategies, again for teaching strategies, and a third time for student interactions or behavior, etc. This repeated viewing would allow the preservice teacher to see the lesson in more depth and view the complexity of each lesson in more detail, possibly allowing them to transfer those same skills to face to face observations. Due to the similarity of findings across both the treatment and control groups, key refinements to the intervention model are suggested. These include: 1) identifying videos that are more reflective of authentic classroom observations, 2) refining the observation protocol to emphasize observation of general classroom environment conditions, 3) broadening the use of the observation protocol as a framework for debriefing sessions, and, 4) adding a debriefing session after the school observations. The model proposed here should be considered one that is very generic in form. That is, it is applicable to a variety of classroom settings across the K-5 grade levels. However, there are a number of perspectives and considerations that do have possible implications for the model presented. As noted previously, preservice teachers in the early experience course are limited in their prior knowledge of both curricular context and instructional strategies. As a result, they are not prepared to evaluate the appropriateness of either context. However, they can certainly denote the content and instructional strategy observed in the 22 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS classrooms they observe and visit in a manner that can be addressed in follow-up discussions. In conclusion, this research examined implementations of guided observational practices that were informed by the theory of Pedagogies of Practice (Grosman et al., 2009) using an Instructional Systems Design framework (Dick, Cary & Cary, 2011). Preservice teachers were provided with professional representations of teaching practice through the use of video clips and then afforded the opportunity to analyze that professional practice through the use of observation protocols and debriefing sessions. It is through such practices that this elementary education program hopes to build the foundation of conceptual understandings of professional practices for these preservice teachers early in their program of study so that when they move on to their supervised fieldwork, they will be ready to participate in the final phase of Grosman’s theory, approximations of practice, most effectively. References Author (2009, May). Multimedia observations: Examining the roles and learning outcomes of traditional, CD-ROM based, and videoconference observations in preservice teacher education. Current Issues in Education [Online], 11(3). Available: http://cie.ed.asu.edu/volume11/number3/ Brown, J.S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989, Jan/Feb). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 32-42. 23 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Brophy, J. (Ed). (2004). Using video in teacher education. Elsevier: Amsterdam Creswell, J.W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA. Del Prete, T. (1997, Fall). The “rounds” model of professional development. From the Inside, Fall(1), 72-73. Dick, W., Cary, L. & Carey, J.O. (2011). The systematic design of instruction (7th edition). Pearson: Columbus, OH. Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L .(1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL. Grossman, P., Compton, C., Igra, D., Ronfeldt, M., Shahan, E., & Williamson, P.W. (2009, September). Teaching Practice: A Cross-Professional Perspective. Teachers College Record, 11(9), 2055-2100. Hebert, R.S. & Wright, Scott M. (2003). Re-examining the value of medical grand rounds. Academic Medicine, 78(12), 1248-1252. Hult. R.E., & Edens, K.M. (2001). Videoconferencing: Linking university and public school classroom experiences. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Seattle, WA. Marsh, B., Mitchell, N., & Adamczyk, P. (2010). Interactive video technology: Enhancing professional learning in initial teacher education. Computers & Education, 54, 742-748. 24 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS McDevitt, M. (1996). A virtual view: Classroom observations at a distance. Journal of Teacher Education, 47(3), 191-195. Putnam, R.T., & Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29(1), 4-15. Sonmez, D., & Hakverdi-Can, M. (2012). Videos as an instructional tool in preservice science teacher education. Egitim Arastirmalart-Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 46, 141-158. Star, J.R., & Strickland, S.K. (2008). Learning to observe: Using video to improve preservice mathematics teachers’ ability to notice. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Educator, 11, 107-125. Thompson, S., & Cooner, D.D. (2001). Grand rounds: Not just for doctors. Action in Teacher Education, 23(3), 84-88. Zenger, J.F. (2003). USC “Rounds”: Enhancing the clinical experience Fall 2002Spring 2003. Teacher Quality Collaborative [Online], Available: http://tqc.ed.sc.edu/year4rounds 25 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Table 1 Final Exam Results Category Teaching Strategies Classroom Management Student/Teacher Interactions Students Teacher Treatment Group 36% 21% 20% Control Group 42% 21% 16% 13% 10% 14% 7% 26 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Table 2 Subcategories of Observations in Exams Categories Strategies Content methods/instructional strategies Involving/calling on all students Lesson steps Visuals/music Examples/models Clear directions/states objective Questions Integration Circulating/monitoring/assessing Classroom management Stretch break/breathing Claps/transitions Drum roll Physical arrangement Redirection Management techniques-sticks/hands/eyes on me Time limits Teacher Great job/great teacher Positive/nice/smiling/encouraging Organized/good manager Effective/knowledgeable Student Diverse Excited/engaged Well behaved Bright/smart Uniforms Interactions Positive reinforcement/feedback Comments/kudos/peer interactions Classroom environment Student voice/freedom Respect/positive attitude/trust/relationships Treatment Control 51% 20% 9% 69% 54% 47% 41% 5% 18% 69% 22% 12% 83% 54% 36% 42% 11% 14% 40% 33% 14% 49% 20% 97% 1% 43% 33% 20% 22% 15% 7% 1% 41% 35% 18% 7% 37% 28% 11% 7% 4% 52% 31% 7% 2% 29% 56% 13% 5% 5% 45% 31% 35% 11% 72% 36% 43% 39% 18% 28% 27 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Table 3 Reflections Results Category Self Strategies Classroom management Students Interactions Teacher Unexpected events Treatment 31% 18% 18% 13% 12% 7% 3% Control 36% 20% 19% 14% 10% 3% 1% 28 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Table 4 Points of Discussion in Debriefing Sessions Professor Professor Professor Professor Professor Professor Professor A A A A A B B Clear goals/directions/ X X X X X objectives Technology X X Visuals X X X Examples X X X X Organization X X X X X Meaningful/relevance X X X X Differentiation X Physical arrangement of X X X the classroom Questions X X X X X X Kids engaged/active/ X X X X X X interacting Fun X Mgt tech-routines, X X X X X expectations, transitions* Acknowledges X X responses/positive feedback Classroom environment X X Teacher & student X X X X relationship/respect Teacher is X X X positive/animated/ caring Teacher is effective X X Prior knowledge X X X Content methods/ X X X X X instructional strategies Monitor/circulate/assess X X X Redirection X Lesson steps X Note. *Mgt = Management. 29 IMPLEMENTATION OF GRAND ROUNDS: NOVICE OBSERVATIONS Clas sroom Obs ervation Pro to col f or VGR Projec t Classroom Observation Elements --------------General --------------Organization -- ---- Student Engagement -- ---- Deepening Student Thinking -- ---- Affective Classroom Quality --------------Subject-Specific Pedagogy Focused observation of representative K -5 classrooms Focused observation of representative K-5 classroom video snippets (with faculty guidance) Clinical judgements Re: Classroom characteristics observed Follow-Up discussion Re: Classroom observations Evaluative responses of participating students Note- ( Subject-Specific Pedagogy ): Lesson Goals, Introduction,Instruction, Check for Understanding, Guided P ractice, Independent Practice, Closure Figure 1. This figure represents the Video Grand Rounds process in an early experience course.