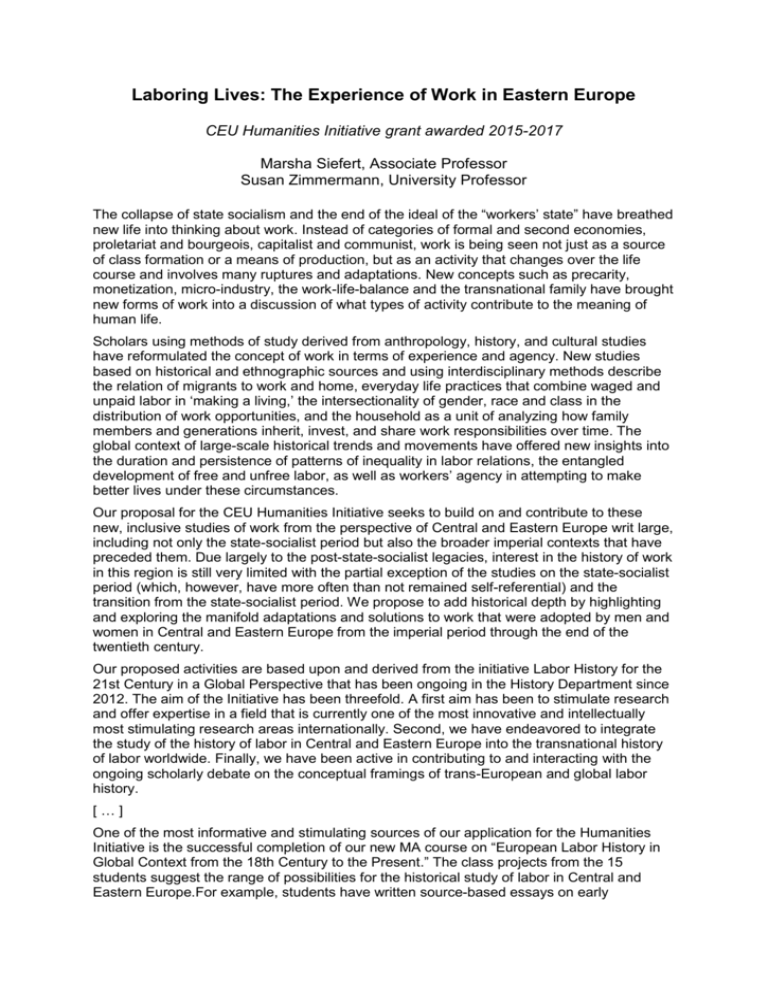

Laboring Lives: The Experience of Work in Eastern Europe

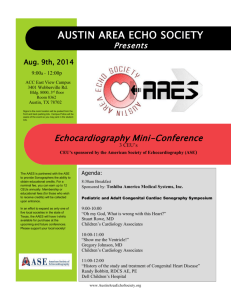

advertisement

Laboring Lives: The Experience of Work in Eastern Europe CEU Humanities Initiative grant awarded 2015-2017 Marsha Siefert, Associate Professor Susan Zimmermann, University Professor The collapse of state socialism and the end of the ideal of the “workers’ state” have breathed new life into thinking about work. Instead of categories of formal and second economies, proletariat and bourgeois, capitalist and communist, work is being seen not just as a source of class formation or a means of production, but as an activity that changes over the life course and involves many ruptures and adaptations. New concepts such as precarity, monetization, micro-industry, the work-life-balance and the transnational family have brought new forms of work into a discussion of what types of activity contribute to the meaning of human life. Scholars using methods of study derived from anthropology, history, and cultural studies have reformulated the concept of work in terms of experience and agency. New studies based on historical and ethnographic sources and using interdisciplinary methods describe the relation of migrants to work and home, everyday life practices that combine waged and unpaid labor in ‘making a living,’ the intersectionality of gender, race and class in the distribution of work opportunities, and the household as a unit of analyzing how family members and generations inherit, invest, and share work responsibilities over time. The global context of large-scale historical trends and movements have offered new insights into the duration and persistence of patterns of inequality in labor relations, the entangled development of free and unfree labor, as well as workers’ agency in attempting to make better lives under these circumstances. Our proposal for the CEU Humanities Initiative seeks to build on and contribute to these new, inclusive studies of work from the perspective of Central and Eastern Europe writ large, including not only the state-socialist period but also the broader imperial contexts that have preceded them. Due largely to the post-state-socialist legacies, interest in the history of work in this region is still very limited with the partial exception of the studies on the state-socialist period (which, however, have more often than not remained self-referential) and the transition from the state-socialist period. We propose to add historical depth by highlighting and exploring the manifold adaptations and solutions to work that were adopted by men and women in Central and Eastern Europe from the imperial period through the end of the twentieth century. Our proposed activities are based upon and derived from the initiative Labor History for the 21st Century in a Global Perspective that has been ongoing in the History Department since 2012. The aim of the Initiative has been threefold. A first aim has been to stimulate research and offer expertise in a field that is currently one of the most innovative and intellectually most stimulating research areas internationally. Second, we have endeavored to integrate the study of the history of labor in Central and Eastern Europe into the transnational history of labor worldwide. Finally, we have been active in contributing to and interacting with the ongoing scholarly debate on the conceptual framings of trans-European and global labor history. […] One of the most informative and stimulating sources of our application for the Humanities Initiative is the successful completion of our new MA course on “European Labor History in Global Context from the 18th Century to the Present.” The class projects from the 15 students suggest the range of possibilities for the historical study of labor in Central and Eastern Europe.For example, students have written source-based essays on early 20thcentury dock workers, both the Ottoman boycott against the Austro-Hungarian Empire and a strike in the multicultural city of Rijeka. Autobiographies have been of particular interest, including an analysis of interwar Polish peasant biographies. Women’s work also emerged as a critical topic, from women’s labor activities during the 1919 Versailles conference to justice for food workers in early 20th century labor law. The state socialist period also yielded several promising research topics, from forced labor in late 1940s Czechoslovakia, a Czech labor collective in interwar Kyrgyzstan, and contract labor in the Yugoslav film industry. These topics suggest how fertile a field the new labor history has become and can continue to be here at CEU. Finally, we propose our project on “Laboring Lives: The Experience of Work in Eastern Europe,” as a way to integrate the humanistic study of labor into the new mission of CEU. First, and most obviously, the history of labor has much to do with understanding the social – both the social mind and social justice. The inequalities of labor relations over time stem from differing social groups and opinions held by the workers and those for and with whom they work. Labor movements have represented an important avenue for seeking social justice, especially in the recent centuries but even in earlier times through slave revolts from below or abolition movements from above. In our reading of the literature on the new global labor history, the representations of race, class and gender figure prominently in the ways in which legislation is proposed and new formations of work practices are instigated. The history of labor as a social force in governance and decision-making is clear; recovering those moments of labor influence, experiments in labor participation in governance, and the conceptual role of labor in larger paradigms of governance would offer much to understanding how human beings govern themselves. Finally, labor history is intertwined – in the recent centuries – with the history of industrialization based in part on transformations provided by new forms of energy, whether steam, electric, or digital. Labor is present and indeed essential to all of the new intellectual themes for the future development of CEU. The CEU Humanities Initiative funds a number of our activities, including a one-year postdoctoral fellowship at the History Department, two series of distinguished lecturers, and work associated with the co-edited volume, Labor in State Socialist Europe after 1945: Contributions to Global Labor History.