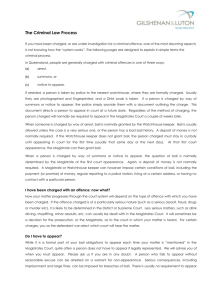

Using the Bail Act 2013 as Amended by the Bail

advertisement