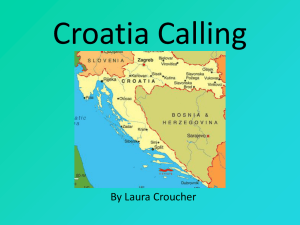

technical assessment - Documents & Reports

advertisement