MASTER*S PROGRAM IN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY

advertisement

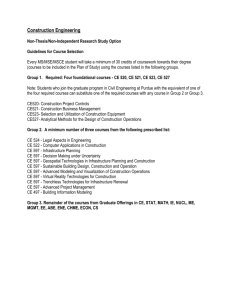

MASTER’S PROGRAM IN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY Historical archaeology is a rapidly expanding subfield of anthropology. In recent years, the field of historical archaeology has acquired an increasingly global focus, attracting the attention of cultural anthropologists, historians, sociologists, and geographers to the potential offered by the material record for illuminating such broad issues as colonialism and its impact worldwide, the historical roots of globalization, and the social history of the disenfranchised. Indigenous and enslaved peoples, both within the U.S. and abroad, have looked to historical archaeologists for help illuminating their experiences under colonial domination and dislocation. Similarly, historical archaeologists have become leaders in interdisciplinary projects that study industrialization, urbanization and their social and their environmental impacts. Such research agendas coupled with the economic importance of historic preservation and its links to tourism have greatly expanded the visibility of historical archaeology and its successes. The M.A. program at UMass Boston plays a key role in training students to participate in this research and public effort. Unlike many other programs in the U.S. that offer M.A. degrees in archaeology, the UMass Boston program is currently devoted solely to historical archaeology and its integration with anthropology and history. It has a strong thematic research focus on both material culture studies and environmental analysis, a combination that gives it a unique and far-reaching character. The sharpness of focus yet depth of coverage are made possible by the significant number of historical archaeologists and associated colleagues in the program’s primary academic departments and affiliated research center, and their joint commitment to critical themes in historical archaeology and to ongoing field and laboratory research of diverse kinds. From the social and environmental consequences of institutional and ideational differences among European colonial regimes to the forging of multicultural societies and national identities in the U.S. and in Latin America, the program is an important voice in the discussion of historical processes related to colonialism, industrialization, urbanization, globalization, and the birth of the modern political economy. History of the Graduate Program The UMass Boston graduate program in Historical Archaeology began admitting students in 1981. Because of University administrative strictures in place at that time concerning the creation of new graduate programs, the program was constructed as one track among three offered within the History Department’s M.A. degree, despite its initiation from Anthropology Department faculty. The program was also designed as a specifically historical archaeology degree and not a generalized archaeology or even anthropology one, again due to the particular administrative environment in place in this first decade after UMass Boston’s founding. Students were admitted to the program by a History Department graduate studies committee on which the Historical Archaeology graduate program director, a member of the Anthropology Department, served. M.A. theses were supervised by committees that included faculty from both departments. 1 In AY01-02, as a function of a greatly expanded set of faculty and staff resources in the Fiske Center and the Anthropology Department over the previous three years and the rapidly growing popularity of historical archaeology nationwide as part of a historically-minded anthropology, the Department began considering ways to make the graduate program work more efficiently and to align more intellectually with broader Department objectives. We concluded that the existing array of graduate courses and course requirements did not take full advantage of the Department’s resources or analytical developments within the field, nor did the program’s structural place within the History M.A. parallel the direction taken by other historical archaeology programs in the U.S. As a result, a major overhaul of the graduate curriculum was initiated in AY02-03 in consultation with the History Department, which ceded administrative control of the program to Anthropology. In AY04-05, the newly formed Graduate Committee in the Department, which consisted of the Graduate Program Director (Professor Stephen Mrozowski), other Department faculty associated with historical archaeology (Professors Amy Den Ouden, Stephen Silliman, Judith Zeitlin), and Fiske Center senior staff archaeologists (Drs. David Landon and Heather Trigg), prepared a proposal to shift full degree control and granting authority to the Department. As before, this transfer of a free-standing M.A. program was enacted with cooperation of the History Department, particularly in our arrangement to require one History course (“Atlantic History”) of all of our graduate students and to permit our students to take select History graduate seminars to fulfill elective requirements. This proposal was successful, and by the time we admitted students for the Fall 2005 semester, the new program was operational and therefore covers almost the entirety of this AQUAD review period. All previous graduate seminar course numbers in the 500s were up-numbered to the 600s to reflect the degree-granting status of our program. The Fall 2005 semester also had the installation of Professor Stephen Silliman as Graduate Program Director, a capacity in which he still serves. Later additions to the Graduate Program Committee came via new Fiske Center hires in 2006 with Dr. John Steinberg and 2008 (joining the Graduate Committee in Spring 2009) with Dr. Christa Beranek. The graduate program in Historical Archaeology does not have a dedicated full-time faculty. All Anthropology courses are taught and all graduate students are advised by full-time members of the Anthropology Department or Center senior staff, who have ongoing responsibilities in undergraduate teaching, administration, and sponsored research. For the majority of the AQUAD period, the members of the Graduate Committee have consistently been Professors Den Ouden (until Fall 2010), Mrozowski, Silliman, and Zeitlin from the Department faculty and Drs. Beranek, Landon, Steinberg, and Trigg from the Fiske Center. The Committee, guided by the Graduate Program Director, makes all admissions decisions, reviews thesis proposals, develops and schedules curriculum, and handles all programmatic and administrative aspects of the graduate program. Participation in graduate teaching and committee work by others – Professors Addo, Martinez-Reyes (anticipated), Negron, and Sieber as well as Dennis Piechota, the Fiske Center conservator – has also been welcomed and encouraged. Structure of the Graduate Program The M.A. program is designed for two complementary objectives: (1) to begin a student’s advanced degree path with coursework, research, and training that will successfully prepare her 2 or him for completing a Ph.D. and (2) to provide solid methodological, theoretical, and topical grounding for students seeking jobs in cultural resource management, museums, non-profit organizations, heritage tourism, secondary education, government agencies, or community colleges. To insure graduate competitiveness in either or both of those directions, the graduate program has a triple commitment to theory and concept, to grounded material and environmental studies, and to community-based work. Those graduate successes are assessed later in this section. Curriculum As outlined in the “Graduate Student Handbook” (Appendix XX), which has been revised a few times over the last few years to improve and update it, the structure of graduate program requires that students take eight graduate courses, four of which are required and four of which are electives chosen in consultation with the student’s faculty advisor. Three core Anthropology courses are required: Anth 625 “Historical Archaeology,” an in-depth survey of current research in the field, taught during the AQUAD period by Professor Mrozowski; Anth 640 “Archaeological Methods and Analysis,” an advanced course in the practice of historical archaeology in the field and laboratory usually taught by Dr. Landon but sometimes Professor Silliman; and Anth 665 “Graduate Seminar in Archaeology,” a graduate course on the history and implementation of archaeological theory that is usually rotated between Professors Mrozowski and Silliman. A History Department offering, Hist 685 “Topics in Atlantic History,” was developed specifically to partner with our program, and it examines important themes in the history of the post-Columbian Atlantic world. Careful planning of the curriculum, starting during the early years of the AQUAD period, resulted in a formalization of annual course schedules to develop a cohort-style graduate group that proceeded in a logical fashion through the required courses. Anth 665 (theory) and Anth 640 (methods) are now offered, and have been for a few years now, in the fall semester and required of all first-year graduate students. These two courses lay the intellectual groundwork for doing historical archaeology. Anth 625 (historical archaeology) is offered every spring as the culmination of theory and practice into a seminar on topical themes and research questions. Like the two fall cohort classes, this one is required of all first-year students. Starting a few years ago, the Graduate Committee decided that we could improve graduation rates and quality of proposals if proposal writing was made a key element of this spring seminar. Although not quantifiable, this adjustment has had significant success in orienting students to the proposal and subsequent thesis processes at an earlier and critical point in their graduate career, given anecdotal evidence from our improved graduation rates in the last three years and student feedback. Accompanying the regular semester offerings is a six-credit graduate-level archaeological fieldwork requirement. Most students meet this requirement through one of the UMass Boston summer field schools, which have been offered during the AQUAD period at field sites in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. Students obtain additional field and laboratory experience through faculty and Center research initiatives, which are discussed more fully below. Among the regular term elective offerings in Anthropology and History are four graduate courses developed alongside the proposal and taught by Department or Center personnel. Anth 3 630 “Seminar in the Prehistory of the Americas” is a discussion seminar that runs concurrently with one of four undergraduate lecture courses in regional Indigenous archaeological histories that precede and enter into the time of European settlement. On one occasion, it has been taught as a stand-alone seminar to meet student needs and scheduling requirements. This course has been taught by Professors Silliman and Zeitlin. Anth 645 “Topics in Environmental Archaeology” is a laboratory-based course that explores the tools and techniques archaeologists use to investigate the interrelationship between cultures and their environments. It taps into the tremendous strengths and core focus of the Fiske Center and is usually taught by Dr. Trigg with some input from Drs. Steinberg and Landon, as well as Dennis Piechota. Anth 670 “Research Methods in Historical Anthropology” focuses on both historiographic methods and analytical perspectives in document-based anthropology. It has been taught by both Professors Den Ouden and Zeitlin. Finally, Anth 672 “Culture Contact and Colonialism in the Americas” draws on diverse case studies from North and South America to examine the complex relationships forged between indigenous peoples and colonists. Rotating through this course as instructors have been Professors Den Ouden, Silliman, and Zeitlin, although the latter two have taught it more recently. These and other elective courses are normally offered on a two- or three-semester cycle to assure their availability to all entering students. To complement these elective offerings, we have both long-standing and new courses appearing in the AQUAD period to diversify and deepen our students’ classroom experiences. In terms of pre-existing courses, Anth 615 “Public Archaeology” has been offered once during the AQUAD period with a previous graduate of a program at the helm who has many years of experience New England cultural resource management. Dr. Beranek has also developed and taught (in Fall 2011) a Special Topics course entitled “Material Life in New England,” a course which we plan to formalize into a regular elective course. At the encouragement of the Graduate Committee, Department faculty members specializing in cultural anthropology have developed additional graduate seminars. Anth 673 “Anthropology of the Object” was developed and taught twice (first as a “Special Topics” course) by Professor Ping-Ann Addo to introduce our students to the ethnographic and theoretical issues surrounding material culture, which we found to be a necessary framework for archaeologists. An earlier, more archaeological version of this topic was handled in Fall 2007 as a “Special Topics” course by a guest professor, Dr. Diana DiPaolo Loren, from Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology. Anth 674 “Tourism, Heritage, and Culture” was developed and taught once so far by Professor Tim Sieber to offer graduate students the opportunity to engage with the intersections of past and present through the lens of heritage and tourism. We anticipate its return on a 3- or 4-semester cycle. Finally, Professor José Martinez-Reyes recently developed Anth 676 “Anthropology of Nature, Place, and Landscape” to add a contemporary and ethnographic understanding of environments and their cultural dimensions, but he has not yet had the opportunity to offer it. Additional electives are possible. UMass Boston participates in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology-based Center for Materials Research in Archaeology and Ethnology (CMRAE), which provides further laboratory training opportunities for our graduate students as an elective course (Anth 650). Also, a small group of courses from the departments of History and American Studies complete the elective menu (see Appendix XX). They have been taken infrequently during the AQUAD period, but some of the seminars – especially the public history offering in History – have proven useful for our graduate students. In addition, the proximity of 4 our campus to the State Archives, which house the Massachusetts Historical Commission offices, has made it possible for a number of graduate students to take on internships that familiarize them with the state inventory of archaeological sites and with the National Register process. Thesis Process An M.A. thesis is required and must be based on original research using principally archaeological data, but also primary documents, oral history, or ethnographic field results. Each student develops a thesis proposal based on a template provided in the “Graduate Student Handbook” and in consultation with the proposed thesis advisor. A new thesis proposal form was carefully designed and adjusted over the past four years to guide students clearly and succinctly in the proposal writing process. Its implementation in the Anth 625 (historical archaeology) spring seminar, as noted above, has also served as a teaching tool for the instructor to advise students on how to frame, document, and justify research. It also parallels the grant proposal structure (e.g., National Science Foundation or Wenner Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research) that many students may need to understand if they seek external funds in their post-graduate career. These proposals are reviewed by all members of the Graduate Committee (plus occasional supplemental members who would be involved in a student’s proposed thesis work), who assess the merits and shortcomings of each proposal, and then vote on whether it can proceed as is, can proceed if some issues are addressed, or cannot go forward as is. Feedback is conveyed directly to students by their thesis chair, following the meeting and vote. Student research culminates in a written thesis, frequently ranging in length from 70 to 100 pages. The “Graduate Student Handbook” outlines the process for completing this work. The student prepares this document in consultation with their thesis chair. Only when the thesis chair decides that the thesis is ready for committee review does he or she authorize the distribution of the thesis draft to the other two committee members. One of these committee members must be a member of the Graduate Committee, and the other member is frequently drawn from that larger contingent in the Department but may include other anthropologists in the Department or archaeologists/anthropologists outside the University who hold a Ph.D. and have employment or affiliation with other universities or archaeological workplaces. These committee members review and decide on whether the draft is ready for a defense. If not, it returns to the student for revision. If the draft is ready, a defense is scheduled in which the student gives a 15-minute presentation on their work to an open public audience usually consisting of the thesis committee members, other faculty and staff, and fellow graduate students; entertains a 15-20 minute question-and-answer session with the entire audience; and then has a private 20-60 minute session with their three-member thesis committee. We implemented the public defense for the first time during the AQUAD period so that students can share their work with other students and faculty and staff, many of whom do not know the outcomes of otherwise interesting research, and so that they have some practice delivering what equates to a conference presentation. Graduate students pursue a wide range of M.A. thesis topics (see Appendix XX), sometimes working closely with faculty members on their larger and often longstanding projects and sometimes working independently. This often happens through field schools or assistantship 5 tasks. Long-term faculty and staff field projects that have helped to produce 21 graduate student theses during the previous AQUAD period are as follows: African Meeting Houses, Boston and Nantucket, Massachusetts (Landon): 2 theses Eastern Pequot Reservation, Connecticut (Silliman): 6 theses Hassanemesit Woods, Grafton, Massachusetts (Mrozowski, Steinberg): 3 theses Magunkaquog Praying Indian Town, Massachusetts (Mrozowski): 1 thesis Newport, Rhode Island (Landon): 2 theses Sandy’s Point/Smith Point, Cape Cod, Massachusetts (Mrozowski): 2 theses Shelter Island, New York (Mrozowski, Landon, Trigg): 4 theses Skagafjörður, Iceland (Steinberg, Trigg): 1 thesis Other students working on independent or staff/faculty-funded projects have considered plantation social relations on Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, Virginia; fuel use and human activity in the Caribbean; the use of space by women at the Denison House in Boston, smuggling activity and merchant life in Salem, Massachusetts; plant pots and use of greenhouse space at Gore Place in Waltham, Massachusetts; parasite analysis from a privy in Rhode Island, AfricanAmerican settlements in Hyde Park, New York; landscape analysis in Little Compton, Rhode Island; mercantilism and gender in Boston; dairying in Plymouth, Massachusetts; minister life and material culture in Lexington, Massachusetts; industrial archaeology at the Copake Iron Works, New York; spatial studies of soil chemistry at Stratford Hall, Virginia; burned wood and environmental analysis on Nevis in the Caribbean; and archaeology and eco-tourism in Brazil. This diversity of regional and topic foci attests to our ability as a graduate program to advise and assist students working in a variety of contexts, both within our primary focus of New England and also far beyond. Student Body The nature of the graduate program involves more than its structure, curriculum, and research outcomes; its definition comes also from the kinds of students who matriculate. Table XX presents application data for the Historical Archaeology program’s last 17 years. The marked increase in the number of applications that began in 1999 has held steadily, with the single exception of the then Graduate Program Director’s 2001 sabbatical year, which resulted in lower admissions since the graduate program process had not yet become a full committee one. We reached a new threshold of application numbers and corresponding selectivity starting in 2008. We attribute this rise not only to the increased interest in this subfield, but also to the enhanced visibility of our program through the research profiles of Department faculty and Center staff that court national and international attention and through the highly successful graduates of our program who have entered Ph.D. programs around the country and have secured post-graduation jobs in the profession. The program once serviced a primarily local or regional population in its first decade or two, but in recent years our applicant pool has included students from across North America, as outlined below. 6 Table xx. Historical Archaeology M.A. Program application disposition totals per year, with subset since last AQUAD review shown below dotted line. Year Accepted Denied Incomplete Total Enrolled 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 8 8 11 9 8 14 10 5 13 19 15 6 4 4 4 2 5 9 2 8 4 3 0 0 3 4 1 1 3 0 0 9 7 14 12 18 17 11 20 22 7* 21 32 25 5 5 8 6 3 9 7 4 5 11 10 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 12 15 16 15 19 11 14 8 9 8 25 23 17 26 3 0 2 0 2 0 0 23 24 26 41 42 28 40 8 10 8 14 12 10 11 Subtotal (2005-2011) 102 116 7 224 73 Average (2005-2011) 15 17 n/a 32 10 TOTAL 222 167 35 416 146 7 These tabular data can be seen better in chart form, particularly with the addition of graduation numbers from 2005 onward (Figure XX). Figure XX. Chart of admissions data from 1994 to 2011, drawn from data in Table XX. Graduation rates included as well, starting in 2005 and including an estimate for 2011. Note: These are numbers graduated in any given year, and not the number of students admitted during that year who have graduated. The data show a significant increase in applicant numbers over the AQUAD period and, noticeably so, across the entire 17-year span. This signals not only a growing interest by students in the UMass Boston graduate program, but also reveals an increased selectivity in the admissions process by the program. Even though enrollment numbers increased slightly starting in 2002, they have remained, by program choice, in the 8-14 range to keep cohorts reasonable and advising manageable. This translates into an increase in selectivity (measured as the percentage of total applicants offered admission, regardless of total enrollments) from an average of 60% in the 2002-2004 years to 53% in 2005-2008 to 40% in 2009-2011. If selectivity is measured as a function of enrollment numbers from the entire pool of applicants, the most recent 40% figure would drop to 30.5%. This selectivity has another measurable element when comparing the GPA and GRE scores of the applicant pools from 2005 to 2001 (Figure XX). These scores have shown an overall slight but variable increase over the last six years, not only across the entire applicant pool but also in the admitted students. For example, the average GPA for the applicant pool in 2005-2006 was 3.43 with an average of 3.57 for those who matriculated. In 2010-2011, that overall applicant average was 3.46 with an average of 3.64 for those who enrolled. The trend becomes more visible in the GRE score. The average qualitative GRE score in 2005-2006 was 548 for the entire applicant pool and 569 for the students who matriculated; in 2010-2011, the applicant pool average for that same score was 577 and the matriculated students had an average of 610. 8 Figure XX. Chart of average GPA and GRE scores for all applicants, all accepted students, and all incoming students in the 2006-2011 Fall admissions cycles. 9 Beyond quantifiable scores, another measure of the graduate program’s success in attracting topranked students from across North America is the source of those students who matriculate in our program (Table XX). We do not believe that a prestigious undergraduate college background can sufficiently indicate a student’s academic and professional potential, but the representation of those universities does offer a way to evaluate the reputation and success of the graduate program. Compared to the early days of the graduate program when it attracted only students from the Northeast (and often from a reasonable commute distance from Boston itself) or the Chesapeake Bay area, the graduate program now has a much wider reach, having drawn matriculated students from a variety of states (n=24), one U.S. territory (Puerto Rico), and one foreign country (Canada), as well as a wide range of undergraduate institutions (n=49). As might be expected, the graduate students mainly have baccalaureate degrees in Anthropology or Archaeology, but some successful admissions have been secured by students with degrees in Cultural and Historic Preservation, History, and even a student each from Classics and Music. Some of those with Anthropology degrees also double-majored in fields such as English, Geography, and even Aerospace Engineering. Table XX. Undergraduate institutions of admitted and enrolled students, 2005-2011. Adelphi University, NY Bard College, NY Bates College, ME Boise State University, ID Boston University, MA Bryn Mawr College, PA Central Connecticut State College of William & Mary, VA Cornell University Drew University, NJ Franklin Pierce College, NH Gettysburg College, PA Lawrence University, WI University of Mary Washington, VA Mercyhurst College, PA Millersville University, PA Monmouth University, NJ University of Notre Dame, IN Queens College, NY Plymouth State University, NH Pennsylvania State University Randolph College, VA Rutgers University Salve Regina University, RI St. Mary’s College, MD State University of New York, Plattsburgh Texas A&M University Universidad de Puerto Rico Université Laval, Quebec City, QC University of California, Berkeley University of California, San Diego University of Connecticut University of Delaware University of Edinburgh, Scotland University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign University of Massachusetts, Amherst University of Massachusetts, Boston University of Michigan University of Minnesota University of Nevada, Las Vegas University of North Carolina University of North Dakota University of Pittsburgh University of Rhode Island University of South Florida University of Southern Maine University of Vermont University of Virginia Western New England College, MA 10 When our top-ranked applicants chose not to come to UMass Boston it was often to go on to another graduate program. A list of these programs demonstrates who some our “peer” competitors actually are (Table XX). Two conclusions can be gleaned from these data. First, we compete directly with M.A. programs at universities with overall higher research rankings and often larger financial packages than UMass Boston (e.g., University of Arizona, University of South Carolina, Cornell University). Second, more often than not, our competitors for top-ranked applicants are not terminal M.A. programs like ours, but instead prominent Ph.D. programs and associated top-ranked universities with substantial financial aid and fellowship offers (e.g., Brown, Stanford, University of Pennsylvania, University of Maryland, University of Connecticut). Both of these trends indicate that we do not compete against peer institutions, as defined by the University. Instead, we compete in a prestigious arena, and with the financial aid offers that we can extend to students thanks to a combination of University support through the Office of Graduate Studies and the College of Liberal Arts Dean’s Office and through external grants and contracts, we often succeed. In fact, we have regularly obtained students for our M.A. program who had admissions offers – frequently Ph.D. offers – at places such as Boston University, College of William & Mary, Western Michigan University, University of South Carolina, Cornell University, and University of Chicago. However, the high cost of living in Boston, the rising cost of graduate education at UMass Boston, and the inability of graduate assistantship stipends and waivers to offset enough of the cost to attend UMass Boston all result in unfortunate enrollment losses that we might otherwise secure with augmented graduate assistantship support. Table XX. Universities that secured some, but certainly not all, of our top-ranked applicants to whom we had offered admission and usually funding, 2005-2011. Brown University (PhD) College of William & Mary (PhD) Cornell University (MA) Illinois State University (MA) M.I.T. (PhD) Memorial University (PhD) Stanford (PhD) Texas A&M University (MA/PhD) University of Arizona (MA) University of Arkansas (MA) University of Connecticut (PhD) University of Delaware (PhD) University of Glasgow (MA/PhD) University of Maryland (MA/PhD) University of Pennsylvania (PhD) University of South Carolina (MA/PhD) University of West Florida (MA) Western Michigan University (MA) Research Facilities and Opportunities for Students UMass Boston archaeologists are actively engaged in a variety of archaeological research projects that provide opportunities for graduate student participation and cutting-edge training in the use of contemporary technology for archaeological research and analysis. In support of archaeological fieldwork, the Department and Fiske Center maintain a full inventory of excavation equipment, such as shovels, trowels, field cameras and screens. More specialized 11 equipment includes electronic total stations (standard and robotic) for surveying, a digital video camera, a ground-penetrating radar equipment with several antennas, two electromagnetic conductivity instruments, an electrical resistivity unit, and a variety of coring tools for pollen and sediment collection. Graduate students frequently use this equipment as part of their research. The Department also maintains a small curation area for storage of archaeological collections. Graduate students in the Historical Archaeology program analyze artifact collections and other materials recovered from excavations in the UMass Boston archaeology laboratories, and they complete these tasks for their own research projects or as part of faculty and staff grants and contracts. These ten laboratories include: 1) Teaching Laboratory (1200 sq ft), overseen by Melody Henkel, as common space for seminars, meetings, and general processing, complete with physical anthropology and artifact reference collections, fume hood, and sink, plus large tables as layout space; 2) Fiske Center Common Laboratory (1000 sq ft), overseen by Professor Stephen Mrozowski, equipped with cleaning and cataloging supplies, an artifact reference collection, fume hood, sink, computer workstations, table layout space, and lounge area; 3) Zooarchaeology Laboratory (450 sq ft), overseen by Dr. David Landon, containing a faunal type collection, thin section equipment (a lapidary saw, Isomet® low speed saw, and Ecomet® grinder), table layout space, and a computer workstation; 4) Paleoethnobotany Laboratory (450 sq ft), overseen by Dr. Heather Trigg, with equipment equipment and comparative collections for the identification of archaeological wood, seeds, pollen and parasites; plus table layout space, and fume hood. Microscopy resources include 4 compound and 5 dissecting microscopes: one compound microscope has polarizing and Nemarsky optics, and another metallurgical microscope is capable of both reflected and transmitted light. Analytical software includes microscopy imaging and pollen data graphing; 5) Wet Laboratory (600 sq ft), overseen by Dr. Heather Trigg, with a Flote-Tech machine for processing archaeological sediment samples for macrobotanical extraction; soil sample storage; equipment used to prepare and process sediments for loss-on-ignition and phosphate analyses – programmable muffle furnace, colorimeter, analytical balance and digital scale; two fume hoods; sink, and bench layout space; 6) Pollen Processing Laboratory (400 sq ft), overseen by Dr. Heather Trigg, equipped with centrifuge and other extraction equipment for palynology and archaeoparasitology; 7) Special Projects Laboratory (350 sq ft), overseen by Dr. Heather Trigg, Professor Stephen Silliman, and Dr. Virginia Popper, with computer workstation, sink, bench layout space, and extensive soil sample and flotation sample storage; 8) Conservation Laboratory (450 sq ft), overseen by Dennis Piechota, with specialized equipment for freeze-drying and electrolytic treatment of artifacts, hand-held x-ray fluorescence scanner, microscopes, sink, fume hood, and bench layout space; 9) New England Archaeology Laboratory (600 sq ft), overseen by Professor Stephen Silliman, with three bays of curation cabinets, table layout space, two computer workstations, ArcGIS software, flatbed and slide scanners, basic dissecting microscope, and photographic copy stand; and 12 10) Digital Archaeology Laboratory (600 sq ft), overseen by Dr. John Steinberg, with remote sensing equipment, large format scanners and printers, several computer workstations, and ArcGIS and specialized GIS software. Financial Support Financial support for graduate students comes in the form of graduate assistantships (GA) funded by the Office of Graduate Studies, frequently routed through the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, and in graduate research assistantships (GRA) funded by external sponsors. The Fiske Center provides abundant opportunities for graduate students to work on applied archaeology projects during their time at UMass Boston. Center archaeologists direct many externally funded research projects and actively work to involve graduate students in their research. These projects range from specialized scientific analyses of archaeobiological materials to large-scale cultural resource management (CRM) projects. Such projects frequently have a strong public service character, helping historical agencies as well as local, state, federal, and tribal government organizations with the identification, preservation, and interpretation of archaeological sites. Graduate students typically participate in all aspects of these projects, working as supported GRAs on archaeological survey and excavation, laboratory analysis, historical research, and report writing. In some cases the work that students do as GRAs also serves as the basis for their master’s thesis projects. Over the past seven years, the Fiske Center has used externally funded projects to provide approximately $350,000 in graduate student support, including stipends and fee waivers beyond the state-supported tuition waiver. Faculty grants and contracts administered outside of the Center have provided another $42,000 in similar graduate student support. Examples of funded projects include the following: Development of Online Databases of Pollen Related to Human Activities Sponsor: National Science Foundation Total Funding: $61,475 Recipient: Heather Trigg and John Steinberg Graduate student roles: GRA support for summer and academic year laboratory research Archaeological Survey and Excavation at Hassanemesitt Woods Sponsor: Town of Grafton Massachusetts Total Funding: $75,000 Recipient: Stephen Mrozowski Graduate student roles: Site of graduate student field school (2006-2011); GRAs participating in summer field and year-long laboratory work; produced two M.A. theses to date; component of two(??) ongoing MA thesis projects Chiefdom to Manor: Excavations at Large and Small Viking Age Farmsteads in Skagafjörður, Iceland. Sponsor: National Science Foundation Total Funding: $101,718 from Archaeology Program, $190,200 from Polar Logistics in 2007 13 Recipient: John Steinberg, Douglas J. Bolender, Brian N. Damiata, and E. P. Durrenberger. Graduate student roles: Travel support for students participating in summer field research and year-long graduate assistantships; produced one M.A. thesis to date Investigating the Heart of a Community: Archaeology at Boston’s African Meeting House Sponsor: Museum of African American History Total Funding: $84,736 Recipient: David Landon and Leith Smith Graduate student roles: GRAs participating in summer field and year-long laboratory work; produced two M.A. theses to date; component of one ongoing MA thesis project Centuries of Colonialism in Native New England: An Archaeological Study of Eastern Pequot Community and Identity Sponsor: National Science Foundation Total funding: $114,000 Recipient: Stephen Silliman Graduate student roles: Site of graduate student field school (2006-2009); GRAs participating in summer field and year-long laboratory work; produced three M.A. theses to date; component of six ongoing MA thesis projects Excavation and Geophysics at the Durant-Kenrick House, Newton, Massachusetts Sponsor: Historic Newton Total funding: $24,671 Graduate student roles: Site of graduate student field school (summer 2011); GRA support for laboratory work; component of one ongoing MA thesis project. Augmenting these external funds are the Office of Graduate Studies assistantships that have increased in allocation over the last few years thanks to the deans of both the College and Graduate Studies recognizing the national reputation and active research associated with our graduate program. Altogether, these funds permit us to have offered financial aid packages to an average of 80% of graduate students over the AQUAD period, or more importantly, to 100% of all students entering in Fall 2010 and Fall 2011. Admittedly, we do not have enough funds to support any one student with 100% (FTE) coverage, but we have found that a good recruiting and cohort equity strategy can be achieved if we offer 25% or 50% (FTE) assistantships to all incoming students. With our greater selectivity producing already highly qualified students for our admission cycle, adding funds to these admissions packages has strengthened our recruiting in a competitive graduate admissions market, insured extensive research opportunities for all students, kept internal student money competition to a minimum, and peopled our research projects with interesting and dedicated student workers. Assessing the Graduate Program To assess the outcomes of the Historical Archaeology M.A. Program, the Graduate Committee has employed two different strategies. First, the faculty and staff, especially the Graduate 14 Program Director, keep track of as many graduates and their ultimate disposition in the academic world or the workplace. We also have admissions data for several years that provide unique assessment tools for the graduate program. Second, the Program developed an alumni survey, administered by the online tool www.psychdata.com, in Spring 2011 to acquire a more enriched set of data on the whereabouts and success of our graduates (see Appendix XX). This survey announcement was distributed via alumni database contact information and the Historical Archaeology at UMass Boston Facebook page, a social media resource initiated in Fall 2010. We intentionally limited the survey to graduates of the 2000-2011 period, or what should be about 59 students, and we received a response rate of over 50% with 30 responses. Of those 30 responses, 25 (83%) date to the 2005-2011 period. Post-Graduation Successes That UMass Boston’s Historical Archaeology M.A. program may still be the first choice for a student given the opportunity to embark directly on a Ph.D. is quite remarkable, and it underscores how the program continues to fill a significant niche in the professional training of archaeologists in North America. For students planning to complete a Ph.D. in the future, the M.A. offers an opportunity to acquire intensive hands-on experience in historical archaeology and environmental archaeology, at the same time that our courses offer a theoretically informed approach to the field and to contemporary issues of colonialism, globalization, and heritage. Many Ph.D. programs now prefer students who have already completed an M.A., and the UMass Boston Historical Archaeology program has been gaining wide recognition for the quality of its graduate training. Seventeen (35.5%) of our 45 graduates between the period 2002-2010 have gone on to pursue a Ph.D. at such prestigious institutions as University of California Berkeley, University of Pennsylvania, Stanford University, Boston University, Syracuse University, and others, often with substantial tuition and financial aid packages (Table XX). Two of the program’s graduates during this period have now completed their Ph.D.s and have tenure-track archaeology jobs at the University of Minnesota and the University of Leicester in the U.K. Table XX. Universities to which our M.A. graduates have gained entry for Ph.D. training in Anthropology (unless otherwise noted), 2002-2011. Binghamton University (SUNY) Boston University (2) Clark University [History] Federal University, Bahia, Brazil Indiana University Michigan Technological University Southern Illinois University, Carbondale Stanford University Syracuse University University of Arkansas University of California, Berkeley (3) University of Connecticut – Storrs University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill University of Pennsylvania University of Minnesota, Minneapolis University of Virginia University of Tennessee (2) 15 For those who choose to enter the work force after graduation, varied opportunities for archaeologists exist in the public and private sector (Table XX). Academic positions are difficult without a Ph.D., but one graduate does work as an instructor at Bridgewater State University in Massachusetts. On the other hand, cultural resource management (CRM) traditionally employs the largest number of archaeology M.A.s in the United States, and that has been true for the UMass Boston program as well. Of the 30 respondents, 7 work for CRM companies (e.g., Public Archaeology Laboratory, Pawtucket, Rhode Island [4 graduates]; Bison Historical Services, Calgary, Alberta; EnviroBusiness, California), and we are aware of at least one other graduate working in Colorado for SWCA Environmental Consultants and another who recently worked for Independent Archaeological Consulting in New England. Many of our graduates who have gone on to Ph.D. training worked in the CRM world for a year or more during their final years in our M.A. program or immediately following graduation. In addition, 3 who completed the survey hold government regulatory positions at the Massachusetts Historical Commission [2 graduates] and North Carolina Department of Transportation that involve archaeological review, mitigation, and/or Geographic Information Systems work. Another 2 graduates work for Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest in Virginia in an archaeological capacity, and a third graduate works as a tour guide for the Adams National Historical Park in Quincy, Massachusetts. Our strong connections with local museums and general training in material culture and public history have seen 4 graduates securing jobs at the Peabody Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology at Harvard University; the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts; the Robert S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology in Andover, Massachusetts; and the Comanche National Museum in Oklahoma. Still others have employment as the House Director at the Dana Hall School and as customer service representatives. The unemployed respondent indicated that s/he would prefer an archaeology-related job, but currently cannot secure one. Table XX. Career directions for recent graduates of the M.A. Program (30 respondents, plus 3 additions from personal knowledge) Job Category Cultural resource management Ph.D. programs Museums / Preserves / National Parks Government regulatory positions in archaeology Academic positions (pre- or post-PhD) Miscellaneous Unemployed TOTAL Number 9 8 7 3 3 2 1 33 Value and Usefulness of Graduate Education These academic and employment directions are excellent indicators that our graduates have fared well in their post-UMass Boston pursuits. Although these serve as a decent proxy for the quality 16 of our training and hopefully overall graduate satisfaction, we included numerous questions in the alumni survey to assess the levels of satisfaction and usefulness more directly. One question asked how well graduate students feel that we provided something useful in terms of skills and perspectives, with answers structured by a preset number of choices and the option to add something under an “Other” category (Table XX). The pattern is telling over the entire 2000-2011 period, but almost all categories saw a noticeable increase between 2007 and 2011, which is a sign of our program conveying more information more consistently. Over the entire span, more than 80% highlighted material culture analysis – a skill that crosscuts archaeology, heritage, museums, and other fields – and clear and effective writing – a skill that transcends any single discipline. This reached 88% in the last 5 years. Another 65-73% of the respondents felt that we also taught critical thinking, teamwork skills, assistance with design and implementation of research, and decision-making abilities in the field or laboratory. Critical thinking also jumped to 88% in the last 5-year span, with the other three all going to 76%. Again, we regard these three as absolutely essential ingredients to a successful graduate program given the transferability of these to all disciplines, many employment sectors, and in overall life experiences and cultural and academic literacy. It is rewarding to see student recognition and use of them increasing in recent years. Strangely, a key element that we had expected to score highly was collaborative approaches, which came in at only 57% in the entire span. However, this has only recently become a strong focus for program teaching and research, and this is borne out by the survey data which shows this emphasis rising to 71% of respondents in the last 5 years. Table XX. Percentage of respondents (n=30) who felt the M.A. program provided a defined set of skills or perspectives. List is ordered by rank for the 2000-2011 period. Skill Set or Perspective Material culture analysis Clear and effective report/paper writing Critical thinking Design and implementation of research Decision-making abilities in the field or laboratory Teamwork Excavation skills Laboratory procedures Proper record-keeping General problem-solving People skills (e.g., communication, negotiation) Archival analysis Collaborative approaches with communities Mapping techniques Humanities perspectives Field surveying techniques Scientific perspectives Federal laws pertaining to archaeological research % (2000-2011) 87% 80% 73% 70% 70% 67% 63% 63% 63% 63% 60% 57% 57% 53% 53% 47% 47% 40% % (2007-2011) 88% 88% 88% 76% 76% 76% 65% 65% 65% 76% 76% 59% 71% 53% 65% 41% 59% 29% 17 Public outreach Statistical analysis State laws pertaining to archaeological research Proficient computer database management and use Geographic Information Systems Museum/exhibit creation Public agency consultation 33% 30% 30% 30% 27% 13% 10% 41% 41% 29% 47% 41% 24% 18% Measured by responses of 30% or under, our weakest deliveries were mainly more technical aspects of research: statistical analysis, state laws, computer database management, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). We acknowledge that we do not focus on statistical analysis on our courses, and only one or two archaeologists on staff use these techniques with proficiency. However, this number increased to 41% in the last 5 years, revealing our increased emphasis. Moreover, we also do not regularly teach our Public Archaeology class, which is the one that could offer the nuts and bolts of state and federal laws pertaining to archaeology. This may explain the drops for federal and state laws, respectively, from 40% to 29% and 30% to 29% across the 2000-2011 to 2007-2011 periods. These two categories comprise the only ones, other than field surveying techniques, to decline between the 2000-2011 and 2007-2011 spans. All others increased. Another noticeable increase can be seen with Geographic Information Systems, as it went from 27% to 41% when considered for the 2000-2011 and 2007-2011 spans, respectively. This is not surprising given that two of our graduates presently do this for a job, several of our graduate students currently work on this computer software, and at least one or two others worked on such systems in a regulatory context before pursuing their Ph.D. This pattern can be even better understood when we looked at the data spread: 7.7% of respondents who received their degrees in 2007 or before acknowledged helpful training in GIS, whereas 41% of those who received degrees in 2008 or after listed it. This almost six-fold increase indicates that we have been moving in a positive direction. However, out of 26 respondents who answered a survey question about what they would change about the program, 27% recommended more courses with GIS and mapping training. In addition, we also score low (below15%) in training students to create museum exhibits and to consult with local agencies over the 2000-2011 span; the data demonstrate that the only students to mention the former at all graduated in 2008 or later and the only ones to mention the latter graduated in 2010 or later. These account for the increased percentages in the last 5-year block. Again, these reflect the addition of different training opportunities in the most recent emphases of our program. In addition to the information conveyed in the academic program, we wanted to know what kinds of topics our graduates potentially learned about in the program that translated into usefulness beyond graduation. As seen in Table XX, these varied over the last 11 years and within the last 5 with almost all categories increasing in graduate usefulness over the more recent periods. For the entire span, between 70% and 77% of respondents found that our coverage of colonialism, ceramics, material culture, and archaeological theory were consistently useful, although the latter fell in the last few years perhaps as a function of our program emphasizing theory more than it did ten years ago in perhaps a slight disproportion to its usefulness outside of academia. The categories of colonialism and ceramics definitely increased in percentage when bracketed to the 18 last 5 years. We thought the ceramics aspect might be useful, given the wealth of these data in historical archaeology, but we were glad to see that understanding colonialism was the most useful to the entire group than anything else. Beyond our program, however, our graduates have found much less useful (17% or less) the topics of stone tools, religion, and museum studies, although these percentages have risen significantly over the last 5 years. We wonder, though, if the lack of usefulness of museum studies is, in part, because we have not taught it consistently, as demonstrated in the previous table. Otherwise, we have quite a few graduates working in the museum world where such skills would prove relevant and more courses by Dr. Christa Beranek and Professor Ping-Ann Addo would be helpful. Revealing perhaps is the lowest category of usefulness: problems that affect my home community or region. We assume this means that the graduates have found it challenging to link what they learned in our graduate program to some issues that confront their own community experiences, which is unfortunate. Table XX. Percentage of respondents (n=30) who felt the M.A. program taught them about certain topics that helped them beyond graduation. List is ordered by rank for the 2000-2011 period. Topic % (2000-2011) Colonialism 77% Ceramics 73% Material culture, generally speaking 73% Archaeological theory 70% Environmental archaeology 63% Gender 63% Identity 63% History of archaeology 60% Zooarchaeology 57% Legacies of colonialism 57% Indigenous communities 57% Glass 53% Metal 53% Historical anthropology 50% Historical archaeology / cultural anthropology relationship 50% Politics of research 43% Politics of heritage 43% Paleoethnobotany 40% Conservation 40% Remote sensing 30% Urbanism 27% Repatriation of human remains and/or cultural objects 27% Stone tools 17% Religion 17% Museum studies 13% Problems that affect my home community or region 10% % (2007-2011) 88% 76% 71% 59% 59% 76% 71% 71% 59% 65% 59% 65% 59% 59% 53% 47% 47% 35% 53% 41% 24% 41% 24% 29% 24% 12% 19 To gauge overall satisfaction, the survey also asked students what they liked MOST about the graduate program, and we have excerpted some of their answers, verbatim, here: “The fact that all of the faculty was realistic and understanding. I came to the program with a fairly significant amount of experience, including co-directing a mitigative program. All of the faculty were really open and helpful in recognizing my skills/limitations and helping tailor the program to my needs in such a way to help fill the gaps in my knowledge and experience. Rather than seeing me as a number and a cookie to be cut into a specific form, the faculty saw me as an individual with not just a lot to learn but a lot to contribute as well.” (2005 Graduate) “The non-competitive atmosphere, the faculty, the hands-on experience.” (2008 Graduate) “I really enjoyed the whole experience. Thought all the professors were dedicated to helping me succeed. There were a lot of good opportunities to learn in the program as well.” (2008 Graduate) “The sense of community between the students and the faculty. It was as though almost everyone was supportive of everyone else and ready to help them toward getting the most out of the program. It was clear the goal was to not only to write a thesis and obtain the masters degree, but to do research on a useful and relevant topic that had long term benefits (either in making the student competitive for phd programs or job possibilities).” (2009 Graduate) “Academically, exposure to a wide range of research topics and skills due to the involvement of the Fiske Center research staff in graduate class, work, and thesis committees. I liked the people and the welcoming group atmosphere very much as well.” (2009 Graduate) “The department was very supportive and cohesive, like one big family. It was a very comfortable and open environment, and everyone was very helpful and eager to assist in any way possible. It was not competitive amongst students, and everyone was friendly. There were also many fun fieldwork opportunities and lab opportunities that not many other programs offer that provided very useful and practical experience.” (2009 Graduate) “The research opportunities provided to me were very helpful in developing a well-rounded education in Historical Archaeology. The program's research which includes different geographic regions, time periods, and methods of analysis were great for someone with diverse interests. Plus, I had so much fun!” (2010 Graduate) “It was an overall great experience, so this is a tough question... I think the greater responsibilities I had working on my thesis project, and the confidence that every member of the faculty and Fiske Center had in my abilities.” (2010 Graduate) “I enjoyed the collaborative effort and being able to practice in the field what I learned in seminars with world-class faculty. I also enjoyed being able to have stimulating and interesting discussions in class that related to events and issues relevant to the present as well as the past.” (2010 Graduate) To complement those answers, the survey also asked students what they liked LEAST about the graduate program: 20 “I guess the only thing that was kind of difficult to deal with at times was all the red tape and strange procedures required to get paid, etc., through the bureaucracy of UMass Boston itself.” (2002 Graduate) “Not enough preparation for a career in CRM archaeology- federal and state regulations and compliance-related issues.” (2005 Graduate) “The culture that defines the Fiske Center and academic archaeology on a whole where students are given unrealistic expectations for their careers. Students are encouraged (implicitly and directly) by faculty, students, and the academic sector of the field to pursue Ph.D. programs in archaeological disciplines. However, there are VERY limited jobs and those that do exist are extremely difficult to obtain. Students pursue further graduate work, find themselves in very deep student loan debt, and then are fully-capable to write about archaeological theory but are incapable of understanding the business of archaeology - which is where 95% (or greater) of the jobs in archaeology are located. … I remember liking this culture at UMass the least and hope that this can change because it serves as a dis-service to incoming students.” (2007 Graduate) “The lack of available TA positions in the classroom, the lack of formal GIS training.” (2008 Graduate) “Lack of information about job opportunities, and guidance on ways to have a career in archaeology without pursuing a career in academia.” (2008 Graduate) “Having experience in other programs, I think there could have been more promotion for extra opportunities when they arose (like TAships, additional paying opportunities, or just those geared around experience). It seemed as though students were occasionally given opportunities not based on merit or qualification but through favoritism, etc.” (2009 Graduate) “Dealing with the University Administration, and that the tuition waiver didn't cover ‘fees’ which were just as much as tuition.” (2009 Graduate) “I would have liked to have had more information or classes about federal laws and regulations, like the section 106 process. I also had a lot of experience as a field technician for CRM companies, and felt that a lot of the other graduate students, as part of or in addition to a field school, should have had similar experiences with the cultural resource management side of things in addition to academic work.” (2009 Graduate) “The red tape when it came to getting paid, whether during the year for graduate assistantships or sometimes during the summer for Fiske Center stuff.” (2010 Graduate) “Theory class....I had never been exposed to it in undergrad, so it was extremely difficult for me to be thrown into so wholly. Also, it has not proven to be that useful in my career, I think perhaps a class on law, crm, lab procedures or especially computers would have been more useful. The financial aid/bursar's office were by far the worst part of school at UMB, but I'm not sure that they have much to do with the program itself.” (2010 Graduate) “I wish there had been at least one course offered each semester with a more methodological or practical focus. The theory is good, and it is definitely a strength of the department, but it got extremely repetitive, and I think that offering even short courses on New England archaeology, statistics, or in-depth treatments of any of the topics that were surveyed in 1st-semester Methods 21 or in Environmental Archaeology (for example) would have been more useful in the long run than yet another discussion of identity theory.” (2011 Graduate) A brief analysis of these excerpts reveals several trends. First, sometimes the least positive experience a student had with the graduate program were things not related directly to our program: assistantship payments, fees, and the University administration, or “red-tape” as the several students called it. Second, some students have pinpointed a gap in our program surrounding some of the very practical realities of public and CRM archaeology. They mention a need for more courses on laws, general business practices, and overall career advice and training for those not heading toward Ph.D. programs. Most telling is that out of the 26 respondents who answered a question about what they would like to see included in the graduate program that is not consistently or at all present, 13 (50%) recommended more courses or course content focused on legislation, compliance, and cultural resource management and public archaeology more generally. We have designed the program to meet the dual needs of Ph.D. aspirants and M.A. job-seekers, but this may indicate that some in the latter category do not feel quite enough support. One thing for certain is that we do not quite have enough personnel to regularly teach Public Archaeology, which is the primary class that could cover those practical issues. Third, students often express an interest in teaching assistantships, which have only been able to offer infrequently, although these opportunities have increased in the last two years with new large-section initiatives under the previous dean, Donna Kuizenga. We also asked students what they felt about the Hist 685 “Atlantic History” course, which as described before, was a requirement that we instituted at the time our curriculum moved out of the History Department and into Anthropology. This component had not been formally evaluated other than in anecdotal ways, and the data have proven useful. Out of 21 students of the 30 respondents who took this class, 42.9% found the course useful, 23.8% found it somewhat useful, and 33.3% found it not useful at all. With the retirements or departures of History faculty who have taught this course, we have been considering the best way to handle the course in our overall curriculum. The pattern of responses and anecdotal evidence suggests that we should make Hist 685 an elective, should it even be offered in the near future, and perhaps allow more flexibility in our one History course requirement to let students select that requirement among a slate of pre-selected options. We inquired of our graduates how the assistantship process had worked for them, and the responses are enlightening. The survey had data from 26 respondents (87%) who received assistantship support. When asked if the work was tedious but worthwhile, only 17% found it so; when asked if the work was tedious and not worthwhile, we only had one respondent (3%) attribute such a characterization. Most (68%) found assistantships an easy commitment of research labor for the associated financial offset, and surprisingly only 3% found the amount of support not high enough to even make a financial difference. We know the funds are never quite enough, but at least the students find it a very helpful augmentation to make their graduate education more affordable. When asked if they were too supervised, none agreed, and when asked if they were not supervised enough, only one respondent said he or she was. The pattern suggests that we have achieved a good balance of independent assistantship work and faculty/staff oversight. In fact, 50% of respondents who received assistantships said that they were trained properly before doing their assistantship tasks, and only 3% said they were not trained properly. The other good discovery was that 50% liked the integration that the 22 assistantship offered with other students’ work and with larger faculty and staff projects. Only 10% found the experience isolating, which we imagine has become less of a problem as the laboratories and research projects are more tightly integrated than they once were. We needed to know more about the assistantship as a recruiting tool beyond its implementation once students have arrived. Therefore, we asked in the survey if students had not received funding from us, would they have gone elsewhere. Of the 25 who answered this question, only 28% stated that they would have attended our program regardless because we were their unwavering top choice. Although that result indicates good things about the value a student anticipates receiving from our program, it also demonstrates the absolute importance of assistantship funding for recruiting purposes. A full 36% said they would have likely gone elsewhere, either to follow another funding offer or because they might have found the other unfunded program more suited to their needs. One of this 36% said that she or he could not have pursued graduate work at all without funding. The other 36% said that it would have been a tough decision if they had not received funding from UMass Boston, and they do not know where they would have matriculated. The thesis process itself is a component that we have revised and streamlined over the years, and we wanted a graduate perspective on it. Several questions addressed this. One asked whether the thesis process was a helpful one, with a rating scale of 1 to 5 for “definitely, somewhat, neutral, not really, and not at all.” The average score for the 30 respondents was 1.16, which is a glowing commendation for the thesis process overall. Only two students in that group gave it a neutral score of 3. No one scored their answer lower than this. Our question about whether they received reasonable guidance and help during that process returned a slightly higher (therefore less positive) average of 1.57. Two students registered a “not really” score of 4, and the others not awarding a “definitely” score of 1 gave only 2s (n=5) and 3s (n=3). The aggregate data still indicate that we have performed well in our advising roles. We also wanted to track how much the production of a thesis resulted in career or academic advances for the students beyond the program itself. The results are promising. Of the 30 respondents, 20 of them have presented their thesis research at a professional conference. We did not ask which ones, but we do know from personal experience that numerous students, graduated or still matriculated, have presented their research at regional and national conferences such as the Society for Historical Archaeology, Society for American Archaeology, Council on Northeast Historical Archaeology, and Middle Atlantic Archaeological Conference. In addition, according to the survey, at least 12 published articles or chapters have come from thesis research as well, with students serving as single authors (n=9) or co-authors (n=3). These derive, expectedly, from graduates of several years ago. Some recent examples are: Beranek, Christa M. and Rita A. DeForest 2011 Planting Pots from Gore Place, Waltham, Massachusetts. Ceramics in America 2011, in press. Bowes, Jessica 2011 Provisioned, Produced, Procured: Slave Subsistence Strategies and Social Relations at Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest. Journal of Ethnobiology 31(1):89-109. Cipolla, Craig N. 23 2008 Signs of Identity, Signs of Memory. Archaeological Dialogues 15(2):196-215. Cipolla, Craig N., Stephen W. Silliman, and David B. Landon 2007 ‘Making do’: Nineteenth-century subsistence practices on the Eastern Pequot Reservation. Northeast Anthropology 74:41-64. Gary, Jack 2007 Material culture and multi-cultural interactions at Sylvester Manor. Northeast Historical Archaeology 36(1):100-112. Hayes, Katherine Howlett Hayes 2007 Field excavations at Sylvester Manor. Northeast Historical Archaeology 36(1):34-50. Jacobucci, Susan, Heather Trigg, and Stephen W. Silliman 2007 Vegetation and culture on the Eastern Pequot Reservation: Interpreting millennia of pollen and charcoal in southeastern Connecticut. Northeast Anthropology 74:13-39. Mrozowski, Stephen A, Holly Herbster, David Brown, and Katherine L. Priddy 2009 Magunkaquog materiality, federal recognition, and the search for a deeper history. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 13(4):430-463. Mrozowski, Stephen A., Katherine Howlett Hayes, and Anne P. Hancock 2007 The archaeology of Sylvester Manor. Northeast Historical Archaeology 36(1):1-15. Mrozowski, Stephen A., Katherine Howlett Hayes, Heather Trigg, and Jack Gary 2007 Conclusion: Meditations on the archaeology of northern plantations. Northeast Historical Archaeology 36(1):143-156. Proebsting, Eric 2007 The use of soil micromorphology at Sylvester Manor. Northeast Historical Archaeology 36(1):71-82. Silliman, Stephen W. and Thomas A. Witt 2010 The complexities of consumption: Eastern Pequot cultural economics in 18th-century New England. Historical Archaeology 44(4):46-68. Sportman, Sarah, Craig Cipolla, and David Landon 2007 Zooarchaeological evidence for animal husbandry and foodways at Sylvester Manor. Northeast Historical Archaeology 36(1):127-142. The positive forecast is that every single respondent (100%) from the graduation classes of 2010 and 2011 have considered publishing on their thesis research, and we expect an increase in these attempts and hopefully success in the years to come. This is in contrast to only 35% of all students from the 2000-2008 graduating classes who have not published but have at least considered it. Finally, we wanted to know how likely our graduates would be to serve as ambassadors and representatives for potential applicants. On a scale of 1 to 5 representing very likely, likely, neutral, not very likely, and not likely at all, respectively, our 30 graduates returned an average of 1.33 for how likely they would be to recommend our program to others. The only 4 we received – and removing it produces a 1.24 average for this question – was from a student who took an inordinately long time to complete the degree, who had to go through numerous drafts before she produced an acceptable final thesis, and who had tremendous trouble with the accuracy of billing and accounting between the Bursar’s Office and the Office of Financial Aid. 24 In another section of the survey, she explicitly states that the latter problem would make her hesitant to recommend our program to a student. We find this kind of administrative glitch disheartening for the negative experience it produced. Despite these minority dissatisfactions, the positive news is that the survey revealed quite a bit of “word of mouth” recruitment happening by our graduates. Among the 30 respondents, 9 (30%) have recommended 1-2 potential applicants, 15 (50%) have recommended 3-6, another 2 (7%) have recommended 7-10 people, and 1 respondent (3.5%) has recommended more than 10 prospective students. In terms of recruitment return, these efforts should far outweigh the fact that 3 (10%) of the respondents have recommended no one. Future Objectives [still to be drafted] 25