By Gloria La Riva On September 6, after massive demonstrations of

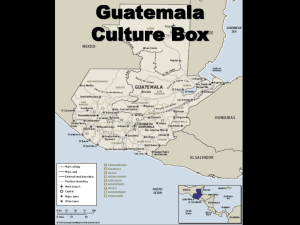

advertisement

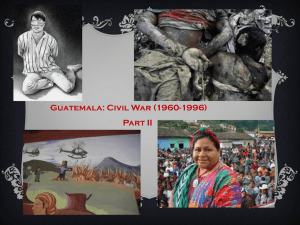

By Gloria La Riva On September 6, after massive demonstrations of upwards of 200,000 people that began last April, right-wing Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina was ousted amid revelations of his direct involvement in an extensive customs-fraud scandal. His vice-president, Roxana Baldetti, was forced to resign in May, being linked to the same fraud scandal. Pérez had no other choice but to step down, since the Congress voted to remove his immunity as head of state and proceed to impeachment. He is now under house arrest, as thousands of documents in evidence are being prepared for his trial. But Pérez is not being prosecuted for a much greater crime, his role as a military general directing the genocidal massacres of indigenous people in the 1980s under dictator Ríos Montt. Indigenous and other progressive forces in Guatemala are demanding Pérez face those charges as well. The current popular protests surprised many political observers, with some in the press comparing them to the actions that sparked the Guatemalan revolutionary struggle of 1944-1954. Those protests provided the impetus for major land and social reforms against the feudal oligarchy, until all was crushed in a 1954 U.S.backed coup. Today, September 6, national elections are taking place in the unusual backdrop of political drama surrounding Pérez Molina. The polls are open for already-scheduled elections of all national offices of President, Vice-President, all 158 deputy seats in the unicameral Congress, 338 municipal districts (corporaciones) and 20 seats in the Central American Parliament. Despite the popular mobilization that drove Pérez out for fraud, today’s elections are not expected to yield a new government leadership that will fight the deeprooted crisis of poverty, drug trafficking and organized crime that rack the country and region. It is common knowledge that many in the government and state apparatus — including some of the 14 presidential candidates — have ties to crime syndicates and the military that waged repression on the people for more than 30 years and reached a terrifying scale in the 1980s. One of them, nationally known comedian Jimmy Morales is running on behalf of the Frente de Convergencia Nacional (National Convergence Front-FCN), an extreme right-wing party led by ex-military generals. Another frontrunner Manuel Baldizón is the most powerful corporate and political figure in Petén, the northern third of Guatemala. He and his party’s leaders of Renewed Democratic Freedom (LIDER) are under investigation for extensive electoral-finance fraud and other charges. Candidate Zulia Ríos is the daughter of the former dictator Ríos Montt. The present is tied to the genocidal past Repression against the indigenous and popular movements was Guatemala’s hallmark after the reversal of the 1944-1954 “Guatemalan Revolution.” It was a period of radical land and social reforms against the feudal oligarchy. Before the 1944-1954 reforms, United Fruit Company was for decades the largest landowner in Guatemala and enjoyed total control of the economy. It paid virtually no taxes while it amassed super-profits, dictated slave wages for workers and peasants, and kept up to 88% of its land uncultivated as landless peasants starved. From 1931 to 1944, Guatemalan military dictator Jorge Ubico provided the favorable climate for United Fruit. But national turmoil among all classes — from liberal elites to the worker and peasant masses — forced Ubico’s overthrow in 1944. Students played a major role in the mass demonstrations. An extremely high concentration of wealth among the top 1%, along with United Fruit, included 75% of the land. President Juan José Arévalo was the first of two presidents in the 1944-1954 reform era. He began a series of labor and other measures that were radicalized by his successor, Jacobo Árbenz Guzman. In a bold measure that is remembered today, Árbenz, elected in 1950, authored and signed Decree 900 accelerating the land reform and expropriating United Fruit’s unused land. Between 1952 and June 1954— just before Árbenz’s overthrow — 1.4 million acres were distributed to the poor. More than 500,000 peasants of the majority indigenous country — 22 Maya ethnic groups, plus Garífuna and Xinca — benefited from the land expropriations. With U.S. interests directly threatened and the fear of Guatemala’s regional influence, the Eisenhower administration unleashed a demonization campaign against Árbenz, accusing his government of being Communist. During the 1950s witch-hunt at home and abroad, such a charge allowed Washington to prepare the terrain for a military coup. The Central Intelligence Agency, under Director Allen Dulles, had already overthrown the Iranian government of Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953, who had nationalized the British and U.S. oil properties. John Foster Dulles, then U.S. Secretary of State, and his brother Allen Dulles, as well as other Eisenhower officials, had close ties to United Fruit Company. With a U.S.-trained army that invaded from Honduras, Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas overthrew Árbenz’s government. The reforms were quickly overturned, and from 1960 to 1996, a bloody civil war was launched against the popular insurgent movement of indigenous peasants, workers and students that had arisen. It was a war of extermination, with 200,000 Guatemalans massacred wholesale. Over 600 rural indigenous villages were eliminated in a terrifying series of bombings and ground operations. The brutality reached a fever pitch under the military dictatorship of General Efraín Ríos Montt, from 1982 to 1983. His rise came under the auspices of the Reagan regime that pumped tens of millions of dollars to back the Salvadoran and Guatemalan military dictatorships in order to destroy those countries’ liberation movements. In the early 1980s, when the Reagan regime was hampered by Congressional blocking of funds, Israel stepped in to provide the Guatemalan army training and its own U.S. Huey and Bell helicopters equipped with heavy-caliber machine guns. Pérez Molina as general, like his overseer Ríos Montt, has direct responsibility for massacres that took place. An extremely shocking scenario of the repression is described by investigative journalist Allan Nairn, in a 2013 interview on the U.S. radio program, Democracy Now, with Amy Goodman.[LIVE LINK TO THE INTERVIEW:] Nairn covered the first trial of Ríos Montt, later convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity. http://www.democracynow.org/2013/4/19/exclusive_allan_nairn_exposes_role_of: “AMY GOODMAN: Talk about how this campaign, this slaughter, was carried out and how it links to, well, the current government in Guatemala today. “ALLAN NAIRN: The army swept through the northwest highlands. And according to soldiers who I interviewed at the time, as they were carrying out the sweeps, they would go into villages, surround them, pull people out of their homes, line them up, execute them. A forensic witness testified in the trial that 80 percent of the remains they’ve recovered had gunshot wounds to the head. Witnesses have—witnesses and survivors have described Ríos Montt’s troops beheading people. One talked about an old woman who was beheaded, and then they kicked her head around the floor. They ripped the hearts out of children as their bodies were still warm, and they piled them on a table for their parents to see. … “AMY GOODMAN: So let’s take this to the current day, to the president of Guatemala today, because at the same time you were interviewing these soldiers, you interviewed the Guatemalan president—at least the Guatemalan president today in 2013. “ALLAN NAIRN: Yes, the senior officer, the commander in Nebaj, was a man who used the code name "Mayor Tito," Major Tito. It turns out that that man’s real name was Otto Pérez Molina. Otto Pérez Molina later ascended to general, and today he is the president of Guatemala. So he is the one who was the local implementer of the program of genocide which Ríos Montt is accused of carrying out.” Ríos Montt, who was finally tried and convicted for the massacre of 1,711 Ixil Mayan villagers, received an 80-year sentence on May 10, 2013. However, 10 days later, in a display of blatant impunity, the Constitutional Court overturned his conviction on procedural grounds. A retrial was ordered for this year, but it has been delayed again. On August 25, the Guatemalan court ruled that Ríos Montt be tried behind closed doors, with no journalists present, due to a diagnosis of dementia. The indigenous survivors of the massacres already forced Ríos Montt to face justice and courageously exposed his crimes. It is doubtful that the new electoral outcome will quell this year’s inspiring new resurgence of protest to demand real and lasting justice.