Transposition of nouns

advertisement

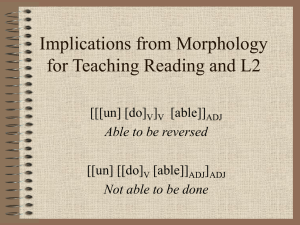

LECTURE 3 Stylistic morphology. Morphology of units. The main unit of the morphological level is a morpheme – the smallest meaningful unit which can be singled out in a word. There are two types of morphemes: root morphemes and affix ones. Morphology chiefly deals with forms, functions and meanings of affix morphemes. Affix morphemes in English are subdivided into word-building and form-building morphemes. In the latter case affixation may be: 1) synthetical (boys, lived, comes, going); 2) analytical (has invited, is invited, does not invite); 3) based on the alteration of the root vowel (write-wrote); 4) suppletive (go-went). There are few language (or paradigmatic) synonyms among English morphemes and only some of them form stylistic oppositions, e.g., he lives – he does live. Come! – Do come! Don’t forget – Don’t you forget. This scarcity of morphological expressive means which is predetermined by the analytical character of the English language is compensated by a great variety of stylistic devices. Morphological stylistic devices as a deliberate shift in the fixed distribution of morphemes can be created by means of: a) the violation of the usual combinability of morphemes within a word, e.g. the plural of uncountable nouns (sands, waters, times), or the Continuous forms of the verbs of sense perception (to be seeing, to be knowing, to be feeling); b) the violation of the contextual distribution of morphemes, which is called form transposition. Stylistic morphology is interested in grammatical forms and grammatical meanings that are peculiar to particular sublanguages, explicitly or implicitly comparing them with the neutral ones common to all the sublanguages. The stylistic potential of the morphology of the English language is one of the least investigated areas of research, especially the stylistic properties of the parts of speech and such grammatical categories as gender, number, person. According to Y.M. Skrebnev, there are two trends of stylistic significance in English morphology: 1) synonymy - paradigmatic equivalence or inter- changeability of different morphemes (dog-s, cow-s – ox-en, phenomenon-a, etc.); 2) variability of use (or inter- changeability) of morphological categorical forms (i.e. component parts of the category) or of members of the opposition that constitute the grammatical category such as tense, person, number, etc. (He is coming next Monday; Well, are we feeling better today?). In both cases, there is a possibility of choice, of using one out of two or more varieties which co-exist paradigmatically. 1 A very powerful stylistic means is morphological transposition (transfer of grammatical meaning, the use of a word not in its primary function but for the purpose of creating a certain stylistic effect). Transposition is the usage of certain forms of different parts of speech in non-conventional grammatical or lexical meanings. In most cases the stylistic function is observed as a result of violation of traditional grammatical valencies, which helps the speakers express their emotions and attitudes to the subject of discussion. Transposition of pronouns 1. Demonstrative – this, these, that, those may be used to express various shades of emotional meanings, attitudes, from admiration to contempt. That beautiful sister of yours! These lawyers! Ох уж эта Настя! 2. Personal pronouns can express cold official relations, indulgence (снисхождение), arrogance (высокомерие), and sympathy: We are exceedingly charming this evening! (“we” is used instead of “you” to express condescending-approving (снисходительно -одобрительный) attitude of the speaker to the young girl. a) the plural of modesty In scientific prose WE implies the author and his imaginary reader. The author's WE, or the plural of modesty, is used with the purpose to identify oneself with the audience or society at large (in order not to mention himself for the reason of modesty but associate himself with his recipients): Now, we come to the conclusion that... b) the plural of majesty WE can be used with reference to a single person, the speaker (instead of the pronoun I). It is called the plural of majesty and is used in royal speech: By the Grace of Our Lord, We, Charles the Second... c) In literary texts (in prose fiction) YOU is used to involve the reader into the action, to make him participate in the events, to impart the emotions prevailing in the narration to the reader (You know). Transposition of nouns 1. The use of singular noun instead of an appropriate plural form creates a generalized, elevated effect bordering on symbolization: The faint fresh flame of the young year flushes From leaf to flower and from flower to fruit And fruit and leaf are as gold and fire (Swineburn). И слышно было до рассвета, как ликовал француз! And on the wave a deeper blue, And on the leaf a browner hue. 2. The abstract noun (normally uncountable) used in the plural form (hyperbolic plural) makes the narration more expressive and brings about aesthetic semantic growth, e.g.: Still waters run deep. When sorrows come they come not single spies but in battalions. 2 Transposition of adjectives Transposition of adjectives turns them into nouns to make the utterance more expressive and tangible (осязаемый): “The Red and the Black”, Isolde the Slender. The grammatical category of comparison (actually the only grammatical category of the English adjective today) is of great stylistic value in the English language. The grammatical category of comparison is only typical of quantitative adjectives, and is not found with relative (non-gradable) ones. So, when non-gradable adjectives denoting qualities normally incompatible with the idea of degrees of comparison (such as colours, physical states, materials) are used in a comparative or a superlative degree, they acquire an evaluative force and become charged with a strong expressive power: pinker, greener; You cannot be deader than the dead (E. Hemingway). The use of comparative and superlative forms with other parts of speech conveys a humorous colouring, e.g.: He was the most married man I've ever met. Violation of grammatical norms of forming degrees of comparison (e.g- the use of synthetical forms with longer adjectives instead of analytical ones) in a literary text serves to reveal the speaker's ruffled emotions (his overemotional state): "Curioser and curioser!" cried Alice (L. Carroll). Verb transpositions The verb possesses more grammatical characteristics than any other Part of speech. All deviant usages of tense, voice and aspect forms have strong stylistic connotations and play an important role in creating a metaphorical meaning. 1. As far as grammatical category of tense is concerned, the most vivid example of grammatical transposition is the so-called Historical (or Dramatic) Present. It implies the use of present forms in order to express actions which took place in the past. Thus, more vivid picture of events is created. The aim of historical present is to join different time systems — that of the characters, of the author and of the reader, all of whom may belong to different epochs. The outcome is an effect of empathy ensured by the correlation of different time and tense systems. In general it is typical of Germanic, Romance and Slavik languages to express an action of the past and the future by means of the present tense. This is explained by the indefiniteness of both notions of "present time" (logical) and "present tense" (grammatical). Writers (Ch. Dickens) often present past events as if they were in the present. “Иду я вчера и вижу…” 2. The auxiliary verb do/does/did in combination with a main-verb is a frequent emphatic device in colloquial speech, e.g.: I do know him; He does look pale; Do let's go to the theatre. Do stop calling me Billy in public! You don’t say! (Да что вы говорите!) 3. The use of Present Continuous into the sphere of Indefinite creates a lot of connotations: Continuous forms employed in different contexts may express: 1) conviction, determination, persistence: Well, she is never coming here again, I tell you that straight (S. Maugham); 3 2) impatience, irritation: — I didn't mean to hurt you.— You did. You are doing nothing else (B. Shaw); 3) surprise, indignation, disapproval: Women kill me. They are always leaving their goddamn bags out in the middle of the aisle (Salinger). Synonymy of morphemes: It can be found in the sphere of affixes. Archaic morphemes are met in bookish, high spheres, not in everyday colloquial sublanguage: тобою, рукою He hath (has), brethren, thou, thy. Archaic forms are employed to create historical, realistic, true-to-life background; to impart solemn and elevated effect; Variation of morphemes: The usage of archaic, colloquial or low-colloquial forms to create certain stylistic connotations. Grammatical archaisms make the utterance solemn and high-flown: taketh, giveth, hath, couldst, thou, thee, etc. The usage of contracted forms to create natural character of speech: is not (neutral) – isn’t (colloquial), ain’t (low- colloquial). Stylistically coloured morphemes are characteristic of certain type of speech. For example, prefixes super-, supra-, hyper-, omni- create bookish connotations, suffixes –y/ie – colloquial (deary, auntie, birdie, girlie). Stylistic effect of emphasis can be created due to repetition of morphemes: She unchained, unbolted and unlocked the door. Questions: 1) 2) Give the definition of the word ‘morpheme’. What types of morphemes exist? What does morphology deal with? 3) What does stylistic morphology study? 1) How are affix morphemes subdivided? 2) Name the types of form-building morphemes. 3) Are English morphemes rich in synonyms? Why/ Why not? 4) How is lack of morphological expressive means compensated? 5) How are morphological stylistic devices created? 6) 7) What grammatical forms and grammatical meanings is stylistic morphology interested in? What are the trends of stylistic significance in English morphology according to prof. Screbnev? 8) What is transposition? What is its function? 9) Explain the functions of main types of morphological transpositions. 10) Give examples of variation of morphemes and repetition of morphemes. 4