- D-Scholarship@Pitt

advertisement

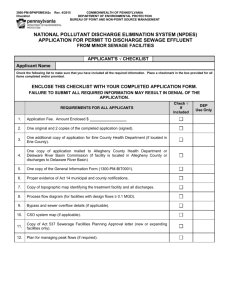

ACCIDENTAL DRUG OVERDOSE FATALITIES ALLEGHENY COUNTY, PA 2007-2011: COMPARISON AND RECOMMENDATIONS by Ashley Lynn Parsons BA, Alma College, 2013 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Department of Epidemiology Graduate School of Public Health in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Health University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH GRADUATE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH This essay is submitted by Ashley L. Parsons on December 2, 2014 and approved by Essay Advisor: Nancy W. Glynn, PhD Assistant Professor of Epidemiology Department of Epidemiology Graduate School of Public Health University of Pittsburgh Essay Reader: Anthony Fabio, PhD, MPH Assistant Professor of Epidemiology Department of Epidemiology Graduate School of Public Health University of Pittsburgh ______________________________________ ______________________________________ Essay Reader: A. Everette James, III, JD, MBA ______________________________________ Professor of Health Policy and Management Director, Pitt Health Policy Institute Department of Health Policy and Management Graduate School of Public Health University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Ashley L. Parsons 2014 iii Nancy W. Glynn, PhD ACCIDENTAL DRUG OVERDOSE FATALITIES ALLEGHENY COUNTY, PA 2007-2011: COMPARISON AND RECOMMENDATIONS Ashley L. Parsons, MPH University of Pittsburgh, 2014 ABSTRACT A report of the drug overdose fatalities in Allegheny County between years 2007-2011 with comparison to peer counties is important to the field of Public Health, because of the implications these findings have on health policy, future monitoring, and targeted interventions to decrease drug use within the county. All deaths of Allegheny County residents coded as X40X499 under the International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems, 10th edition (ICD-10) between 2007-2011 were analyzed to observe and assess trends. A total of 1,055 Allegheny County residents died from accidental poisonings in this time period. Of these deaths 335 were of residents residing within the city limits for Pittsburgh, while 720 were of residents living in the remainder of the county (area not considered to be the City of Pittsburgh). Males had substantially higher age-adjusted fatality rates than females, with average fatality rates for 2007-2011 of 24.3 and 10.1 per 100,000 people, respectively. The largest proportion of deaths within Allegheny County was due to accidental poisonings by and exposure to narcotics and hallucinogens (ICD-10: X42). When comparing Allegheny County to the United States and its peers of Philadelphia, Cook, and Wayne County, Allegheny County had lower age-adjusted iv rates than Philadelphia County, but higher rates than the US, Cook County, and Wayne County. When considering the average fatality rates, Allegheny County had similar poisoning rates between whites and blacks (17.7 and 17.8 per 100,000 people, respectively). This trend was not seen in any other location observed. After analyzing and comparing Allegheny County accidental poisoning fatalities for 2007-2011 it appears that the county is experiencing a drug use problem that warrants investigation and intervention. Future steps to decrease drug use and subsequent death of Allegheny County residents include policy change, monitoring of changes in drug death patterns (movement from urban areas to suburban and rural), consideration of new intervention techniques, and education for residents and physicians. By monitoring future drug overdose fatalities within the county, there is potential to decrease the public health burden of drug use through implementation of targeted interventions and education programs. v TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................... X DISCLAIMER............................................................................................................................. XI 1.0 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 DRUG ABUSE IN THE UNITED STATES ............................................................. 1 1.2 ACCIDENTAL POISIONING & EXPOSURE TO NOXIOUS SUBSTANCES FATALITIES ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.3 PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE ....................................................................... 4 1.4 OBJECTIVE ................................................................................................................ 5 2.0 METHODS ........................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 STUDY POPULATION .............................................................................................. 6 2.2 ALLEGHENY COUNTY DEATH RECORDS ....................................................... 7 2.2.1 Oracle Database ............................................................................................... 8 2.2.2 Age-Adjustment ............................................................................................... 8 2.3 CDC WONDER ........................................................................................................... 8 2.4 DATA ANALYSIS....................................................................................................... 9 3.0 RESULTS ........................................................................................................................... 10 4.0 DISCUSSION ..................................................................................................................... 23 APPENDIX: TECHNICAL NOTES ......................................................................................... 31 vi BIBLIOGRAPHY ....................................................................................................................... 34 vii LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Age-Adjusted Rates (per 100,000 people) of Overdose Fatalities, 2007-2011 by Location………………………………………………………………………………..15 Table 2. ICD-10 Mortality Classification Definitions…………………………………………...21 Table 3. Drug Overdose Fatalities Allegheny County Residents, 2007-2011 by Specific Cause of Death…………………………………………………………………………………..22 viii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. External Causes of Death Classification Diagram…………………………………..…7 Figure 2. Drug Overdose Fatlaities of Allegheny County Residents, 2007-2011 by Sex…….…11 Figure 3. Drug Overdose Fatalities of Allegheny County Residents, 2007-2011 by Location of Residency………………………………………………………………………………12 Figure 4. Drug Overdose Fatalities, 2007-2011: A Comparison Among Peer Counties………...13 Figure 5. Drug Overdose Fatalities in Whites, 2007-2011 by Location…………………………16 Figure 6. Drug Overdose Fatalities in Blacks, 2007-2011by Location……………………….…17 Figure 7. Drug Overdose Fatalities in Males, 2007-2011 by Location………………………….18 Figure 8. Drug Overdose Fatalities in Females, 2007-2011 by Location……………………….19 ix PREFACE I would like to thank my friends and family for their continuous support and understanding during my time in Pittsburgh and throughout my graduate education. My deepest gratitude goes to my advisor Dr. Nancy Glynn for her guidance, patience, and reassurance for the entirety of my graduate career. I would also like to extend my appreciation to my essay committee of Dr. Tony Fabio and Mr. Everette James and to my internship preceptor Mr. John Kokenda for their constructive feedback and encouragement throughout this process. All of your support has paved the way for my future as a Public Health professional and I am truly grateful for all of your time and effort towards my success. x DISCLAIMER The Allegheny County Health Department, Office of Epidemiology and Biostatistics provide these data through a cooperative agreement with the Pennsylvania Department of Health, which requires the following disclaimer: "These data were supplied by the State Health Data Center, Pennsylvania Department of Health, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions." The Bureau of Health Statistics and Research strictly maintain the confidentiality of death certificates. All published reports of vital statistics contain only aggregated data. Individually identifiable information is only released, as provided for in Act 66, Vital Statistics Law of 1953, for health research purposes and to government agencies in pursuance of their official duties upon completion, review and approval of an application for access to protected data. Certified copies are also released to family members or legal representatives for determination of personal or property rights. xi 1.0 1.1 INTRODUCTION DRUG ABUSE IN THE UNITED STATES Historically, the United States has had a large problem with illicit drug use and resulting fatalities; however, since 2005 heroin and cocaine use has plateaued, while prescription drug abuse has grown.1 Between the years of 1999 and 2010 the death rate from prescription opioid use in the United States has increased four-fold. This increase of 4,030 to 16,651 deaths exceeds the combined death toll for cocaine and heroin overdoses in the same time period.2, 3 Likewise, in 2010, prescription opioids were involved in over 16,000 overdose deaths; heroin was implicated in only 3,036.4 A large issue with this shift is that the population that has been most affected by fatalities are those using Medicaid5. The National Institute on Drug Abuse points out that individuals who are 65 years and older are more likely to improperly use their medication and are at highest risk for fatalities due to drug interactions and compounded health problems.6 In 2010, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) found that an estimated 2.4 million Americans used prescription drugs for non-medical purposes for the first time in the past year. Of these prescription drug abusers, the group with highest rate of abuse was young adults aged 18 to 25 years. Young adults were followed by adolescents aged 12 to 17, who accounted for one-third of the drug abusers in 2010. With the exception of the age group 12 to 17 1 years, males had higher rates of drug abuse than females. Commonly abused prescription drugs included opioids, drugs acting as depressants of the central nervous system, and stimulants.6 The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that in the year 2012, 23.9 million Americans aged 12 years and older (9.2% of the population) had used an illicit drug or abused psychotherapeutic medicines in the past month. This rate increased from 2002, when the rate of abuse was 8.3%. The most recent increases in illicit drug use reflect an increase in the use of marijuana. NSDUH shows that most people use drugs for the first time as teenagers—with 2.8 million new users of illicit drugs in 2012. Although new drug users are commonly young adults and adolescents (52% of new users in 2012 were 18 years of age or younger), drug use is increasing rapidly among people in their 50’s. This trend is partially due to the aging of the “baby boomer” generation, which has had much higher rates of illicit drug use than previous cohorts.6 The U.S Department of Health and human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) collects substance abuse trends via survey every year. In 2013, the rate of substance dependence or abuse was higher in males aged 12 or older than the rate for females (10.8 percent in males, 5.8 percent in females). However, when examining the age group of 12 to 17 years, dependence and abuse among males was similar to the rate in females for 2013 (5.3 percent and 5.2 percent, respectively). Also in 2013, the rate of substance dependence or abuse was higher in whites than blacks (8.4 percent vs. 7.4 percent) among individuals aged 12 years or older. The 2013 SAMHSA survey also found that rates of illicit drug or alcohol dependence and abuse was highest in the West (8.9 percent), followed by similar rates in the Northeast and Midwest (8.3 and 8.2 percent), and lowest in the South (7.8 percent). Illicit drug or alcohol dependence or abuse was highest in large and small metropolitan areas (8.6 2 and 8.4 percent), and lowest in nonmetropolitan areas (6.6 percent). 7 These trends indicate that drug abuse and dependency poses the largest burden to white males living in urban areas. As drug abuse rates increase, it would be expected that treatment rates would increase proportionally. However, this is not the case. In 2012, only 2.5 million individuals received treatment, which is approximately 10% of the individuals who needed treatment. Likewise, of those treated, less than 14% were for substances normally associated with high rates of fatalities due to overdose.6 1.2 ACCIDENTAL POISIONING & EXPOSURE TO NOXIOUS SUBSTANCES FATALITIES In the United States, nine out of ten poisonings are accidental drug overdoses. This type of external cause of death has surpassed motor vehicle crash fatalities and is now the leading cause of injury death.8, 9 In regards to demographics, in 2012 whites had the highest death rate for poisoning fatalities compared to blacks. It was also found that in 2011, the majority of emergency department visits (56%) were for males and 82% were for people 21 and older. Likewise, men were 59% more likely than women to die from a drug overdose. The highest death rate for poisoning fatalities in 2012 was to individuals aged 45 to 59, while the lowest death rate for this time period was in children who were less than 15. These trends are also represented in abuse tendencies in these age groups, with adolescents having lower rates of drug use than middle-aged individuals.4 Historically, rural and impoverished counties tend to have higher prescription drug overdose fatalities than higher income areas.10, 11 3 1.3 PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE Drug abuse and poisoning fatalities pose a huge threat to public health and to society as a whole. In 2012, the FBI reported that the highest number of arrests came from drug abuse violations (1,552,432 arrests).12 There is also evidence that shows that drug users are more likely to commit crimes and disrupt society than nonusers. This increase in violence stems from the nature of the drugs that are abused, but is also due to drug trafficking itself. However, how much crime results from drugs is hard to quantify.13 Drug abuse is not only problematic because of the implications it has on crime, but also because of its effect on health care costs. In 2007, it was reported that prescription-opioid abuse cost insurers an estimated $72.5 billion. This cost is similar to that of chronic disease treatments for illnesses such as asthma and HIV.4 Also, in 2009, it was reported that 1.2 million emergency department visits were associated with prescription drug miss use or abuse, which was a 98.4% increase over emergency department visits in 2004. Comparatively, one million emergency department visits were due to illicit drug use.14 With poisoning fatalities increasing across the board and different groups being disproportionately affected, it is crucial that public health leaders and policy makers examine ways in which the rate of drug abuse can be decreased. The first step in changing these outcomes is to examine the areas in which poisoning fatalities are highest and determine which groups are most affected. 4 1.4 OBJECTIVE The objective of this report is to provide an analysis of the trends of accidental drug fatalities in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania between the years 2007 and 2011. Likewise this report will compare the rates of poisoning deaths to Allegheny County residents with those of the United States and peer counties for the same time period. This comparison will allow for the interpretation of the death rates and examine demographic trends. Results of these analyses will help to inform and influence health practice and health policy regarding drug access and fatalities in Allegheny County and in the state of Pennsylvania. 5 2.0 2.1 METHODS STUDY POPULATION The data for this research is from the Allegheny County Health Department, Epidemiology and Biostatistics department, office of Vital Statistics in Pittsburgh, PA. The study population consists of decedents who were residents of Allegheny County and died between the years 2007 and 2011. The subset of the population utilized for this research consists of all individuals whose cause of death was considered to be an accidental poisoning or death due to inhalation of a noxious substance as classified by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition (ICD-10: X40 to X499), Figure 1. 6 Figure 1. External Causes of Death Classification Diagram 2.2 ALLEGHENY COUNTY DEATH RECORDS The variables for this research come from the decedents’ death certificate. These certificates are completed by medical professionals or during an autopsy at a coroner’s office. Once completed, they are sent to the Pennsylvania Department of Health in Harrisburg, PA, for disbursement to the corresponding county health departments. The Allegheny County Health Department receives a physical copy of all death certificates and a digital file to be used for analytical purposes. 7 2.2.1 Oracle Database The digital death certificate information is stored using ORACLE (Version 11G, Release 2). Within the ORACLE database, a program to abstract necessary records has been created. This program identified race, sex, and location (Allegheny, City of Pittsburgh, and Remainder of County) information for all records classified as X40-X499 between 2007 and 2011. 2.2.2 Age-Adjustment Crude number of fatalities were inputted into an excel program to calculate the age-adjusted rates. Age-specific fatality rates were calculated using the 2010 bridged population and age adjusted using the U.S. 2000 Standard Million Population. Adjusted rates were calculated in order to make comparisons across different populations (See Appendix). 2.3 CDC WONDER Allegheny County fatality rates were compared with fatality rates for the United States and other counties of similar size and social structure, as determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The comparable counties selected include Philadelphia County in Pennsylvania, Wayne County in Michigan, and Cook County in Illinois. Age-adjusted rates for the United States and peer counties were derived using the CDC’s Wonder Database utilizing the US 2000 Standard Million Population. The time period of 2007-2011 was used for all counties and ICD- 8 10 cause of death classification of “accidental poisoning and inhalation of noxious substances” (ICD-10: X40-X499) was used to derive all rates. 2.4 DATA ANALYSIS Fatality rates due to accidental poisonings for Allegheny County were analyzed based on location of the decedents’ residence. Three locations were used including all of Allegheny County (the comparator), the City of Pittsburgh, and the Remainder of the County (all of Allegheny County that is not classified as “City of Pittsburgh”)—see Appendix. Median age at death and age-adjusted rates were compared based on location, sex, and race (black vs. white). Age-adjusted rates based on aggregated 2007-2011 data for the United States, Philadelphia County, Wayne County, and Cook County were compared with Allegheny County to examine differences and disparities. 9 3.0 RESULTS Between the years 2007 and 2011, 1,055 Allegheny County Residents died from accidental poisonings or inhalation of noxious substances. Of the poisoning deaths, 335 (31.8%) were from residents living within the city limits of Pittsburgh, while 720 (68.3%) occurred in Allegheny County residents living outside of the city (Remainder of the County). The lowest age-adjusted rate in the five-year period was 12.5 per 100,000 people (year 2007) and the highest age-adjusted rate was in 2011, with 20.2 deaths per 100,000 people (an increase of 61.6%). This upward trend was found in both sexes throughout the time period, as shown in Figure 2. Males had higher rates than females in all years; however, there was a larger increase in rates of fatalities between years 2010 and 2011 in women than in men (10.6 to 14.7 per 100,000 and 24.5 to 26.0 per 100,000, respectively). 10 Age-Adjusted Rate (per 100,000 people) 30.0 25.0 20.0 All 15.0 Males Females 10.0 5.0 0.0 2007 2008 2009 Year of Death 2010 2011 Figure 2. Drug Overdose Fatalities of Allegheny County Residents, 2007-2011 by Sex Figure 3 shows differences between the City of Pittsburgh and the Remainder of the County (all of Allegheny County that is not classified as “City of Pittsburgh”), in regards to overdose fatalities. Overall, Allegheny County experienced an increase in death of its residents from accidental poisonings between 2007-2011 with rates increasing from 12.5 to 20.2 deaths per 100,000 people. It was also observed that there was an increase between 2007 and 2008 (12.5 to 17.9 per 100,000 people) followed by a decline and plateau between 2008-2010 (17.9, 17.0, and 17.4 per 100,000 people, respectively), and an increase from 17.4 to 20.2 deaths per 100,000 people between years 2010 and 2011. The Remainder of the County followed a similar trend as Allegheny County age-adjusted rates; however, the fatalities within the City of Pittsburgh were constant about 22 per 100,000 people during years 2007-2009 and declined in 2010 (19.4 per 11 100,000 people). After 2010, there was a spike in drug fatalities for City of Pittsburgh residents with age-adjusted rates increasing from 19.4 to 26.0 per 100,000 people. Age-Adjusted Rate (per 100,000 people) 30.0 25.0 20.0 Allgheny County 15.0 somewhere on your graph City of Pittsburgh Remainder 10.0 5.0 0.0 2007 2008 2009 Year of Death 2010 2011 Figure 3. Drug Overdose Fatalities in Allegheny County Residents, 2007-2011 by Location of Residency When comparing average age-adjusted rates of accidental drug fatalities between the United States, Allegheny County, Philadelphia County, Cook County, and Wayne County; Allegheny County surpassed all areas except Philadelphia County for the time period observed, Figure 4. Allegheny County had higher fatality rates between 2007 and 2011 than the United States or Cook County, with rates between 12.5 and 20.2 per 100,000 people. Between 2008 and 2011, Allegheny County had higher age-adjusted rates than Wayne County. 12 Age-Adjusted Rate (per 100,000 people) 30.0 25.0 20.0 Allegheny County, PA USA 15.0 Philadelphia County, PA Cook County, IL 10.0 Wayne County, MI 5.0 0.0 2007 2008 2009 Year of Death 2010 2011 Figure 4. Drug Overdose Fatalities, 2007-2011: A Comparison Among Peer Counties A comparison of all age-adjusted rates between Allegheny County, the City of Pittsburgh, and the Remainder of the County is represented in Table 1. The city of Pittsburgh had higher rates than the Remainder of the County (average 22.2 and 15.8 per 100,000 people, respectively. In Allegheny County, the fatality rates increased between years 2007 and 2011, this increase was also seen in the Remainder of the County with rates increasing from 9.9 in 2007 to 19.0 per 100,000 people in 2011. The City of Pittsburgh remand constant around its average fatality rate of 22.2 per 100,00 people for years 2007 through 2010 and increased in year 2011 (26.0 poisoning deaths per 100,000 people). For whites, the City of Pittsburgh had an average fatality rate of 24.2 per 100,000 people, while the Remainder of the County was 16.5. Males were higher than females in all locations, but for the City of Pittsburgh, Males were much higher (33.6 per 13 100,000 people) than the Remainder of the County (22.0 per 100,000). This trend was also seen in the female population with the City of Pittsburgh having a fatality rate of 11.2 per 100,000 people and a fatality rate of 9.9 per 100,000 people for the Remainder of the County. 14 Table 1. Age Adjusted Rates, Overdose Fatalities 2007 to 2011 by Location All Drug Fatalities White Black Males Females Location Allegheny County, PA City of Pittsburgh Remainder of Allegheny County USA Philadelphia County, PA Cook County, IL 2007 12.5 21.3 9.9 9.9 22.5 9.5 2008 17.9 22.1 17.3 10.2 24.7 9.8 2009 17.0 22.2 15.6 10.3 22.8 9.2 2010 17.4 19.4 17.3 10.6 21.4 8.9 2011 20.2 26.0 19.0 10.5 27.5 9.3 Average Rate 17.0 22.2 15.8 10.3 23.8 9.3 Wayne County, MI 13.5 12.8 15.4 13.4 15.9 14.2 Allegheny County, PA City of Pittsburgh Remainder of Allegheny County USA 12.9 23.5 10.3 10.7 18.6 24.5 17.8 11.3 17.6 22.4 16.5 11.4 17.9 19.4 18.2 11.9 21.3 31.1 19.5 13.0 17.7 24.2 16.5 11.7 Philadelphia County, PA Cook County, IL 30.0 7.8 32.2 8.4 29.2 7.9 29.8 9.1 37.3 9.0 31.7 8.4 Wayne County, MI 13.9 14.1 17.3 16.6 20.4 16.5 Allegheny County, PA 13.9 18.7 17.7 20.4 18.4 17.8 City of Pittsburgh Remainder of Allegheny County USA Philadelphia County, PA Cook County, IL 19.2 7.8 8.5 18.1 16.4 19.9 17.5 7.3 20.9 15.8 22.8 12.1 7.3 19.5 15.1 23.3 17.7 7.3 16.2 11.0 14.8 21.4 8.0 21.9 12.7 20.0 15.3 7.7 19.3 14.2 Wayne County, MI 14.3 12.4 14.3 11.2 11.2 12.7 Allegheny County, PA City of Pittsburgh Remainder of Allegheny County USA 20.2 35.7 15.5 13.1 25.6 33.8 24.1 13.6 25.3 36.3 22.0 13.5 24.5 26.8 24.4 13.8 26.0 35.4 24.2 15.1 24.3 33.6 22.0 13.8 Philadelphia County, PA 33.0 36.8 34.1 31.3 42.9 35.6 Cook County, IL 13.8 14.4 14.0 13.7 14.4 14.1 Wayne County, MI 18.7 16.5 21.1 15.6 19.9 18.4 Allegheny County, PA City of Pittsburgh Remainder of Allegheny County USA Philadelphia County, PA Cook County, IL Wayne County, MI 5.4 7.8 4.7 6.6 13.3 5.3 8.7 10.6 10.8 10.7 6.8 14.0 5.3 9.4 9.2 8.8 9.6 7.1 12.7 4.6 10.1 10.6 11.9 10.5 7.5 12.6 4.3 11.4 14.7 16.8 14.1 8.2 13.7 4.4 12.1 10.1 11.2 9.9 7.2 13.3 4.8 10.3 15 Table 1 also shows a comparison of all age-adjusted rates between Allegheny County with the United States, Philadelphia County, Cook County, and Wayne County. Among whites, Allegheny County had rates higher than the United States and Cook County. Allegheny County and Wayne County had similar trends of overdose fatalities between 2007 and 2011 among the White population, Figure 5. Allegheny County had lower rates than Philadelphia County, which exceeded all areas observed for rates of overdose fatalities in whites and had the highest rate for all locations in 2010 (37.3 deaths per 100,000 people). Age-Adjusted Rate (per 100,000 people) 40.0 35.0 30.0 25.0 Allegheny County, PA USA 20.0 Philadelphia County, PA 15.0 Cook County, IL Wayne County, MI 10.0 5.0 0.0 2007 2008 2009 Year of Death 2010 2011 Figure 5. Drug Overdose Fatalities in Whites, 2007-2011 by Location 16 Allegheny County blacks had much higher fatality rates between 2007 and 2011 for poisonings than the United States (Allegheny County ranged from 13.9 to 20.4 per 100,000 people and United States ranged from 7.3 to 8.5 per 100,000 people), Figure 6. This trend is similar to Philadelphia County between years 2007 and 2011. The average age-adjusted rate for accidental drug overdose deaths in Allegheny County was 17.8 and for Philadelphia County it was 19.3 per 100,000 people. The City of Pittsburgh had the highest average age-adjusted drug overdose rate for blacks during this time period, with 20 per 100,000 people. Age-Adjusted Rate (per 100,000 people) 25.0 20.0 15.0 Allegheny County, PA USA Philadelphia County, PA 10.0 Cook County, IL Wayne County, MI 5.0 0.0 2007 2008 2009 Year of Death 2010 2011 Figure 6. Drug Overdose Fatalities in Blacks, 2007-2011 by Location 17 When comparing males and females, Figure 7 and Figure 8, males had substantially higher rates of drug overdose fatalities than females in Allegheny County and all other locations observed for all years. The highest rate for females was seen in the City of Pittsburgh in 2011 with 16.8 per 100,000 people. Allegheny County followed the same trends as the United States, Philadelphia County, and Wayne County with an increase of drug overdose age-adjusted death rates for Females over time. 50.0 Age-Adjusted Rate (per 100,000 people) 45.0 40.0 35.0 30.0 Allegheny County, PA USA 25.0 Philadelphia County, PA 20.0 Cook County, IL 15.0 Wayne County, MI 10.0 5.0 0.0 2007 2008 2009 Year of Death 2010 2011 Figure 7. Drug Overdose Fatalities in Males, 2007-2011 by Location 18 Age-Adjusted Rate (per 100,000 people) 16.0 14.0 12.0 10.0 Allegheny County, PA USA 8.0 Philadelphia County, PA 6.0 Cook County, IL Wayne County, MI 4.0 2.0 0.0 2007 2008 2009 Year of Death 2010 2011 Figure 8. Drug Overdose Fatalities in Females, 2007-2011 by Location Table 3 gives descriptions for all ICD-10 classifications for accidental poisonings and inhalation of noxious substances. As shown in Table 4, the largest number of deaths due to accidental overdoses for Allegheny County residents occurred in X42 (accidental poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and hallucinogens) and X44 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified drugs, medicaments, and biological substances). Classification X42 accounted for 46.2% of deaths within the county and X44 accounted for 43.3%. In Allegheny County the median age at death for all poisonings was 39.2 years. For the City of Pittsburgh and the Remainder of the County the median ages of death were 45.3 and 38.8 years, respectively. In Allegheny County, ICD-10 classification X42 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to narcotics and hallucinogens) had the youngest median age at death with 37.7 years, while X47 19 (Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other gases and vapors) had the oldest with 65.3 years of age at death and accounted for 3% of poisoning deaths within the county. 20 Table 2. ICD-10 Mortality Classification Definition15 X40 4-amniophenol derivatives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (SAID), pyrazolone derivatives X41 Accidental poisoning by and exposure to antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic, antiparkinsonism and psychotropic drugs: Antidepressants, barbiturates, hydantoin derivatives, iminostilbenes, methaqualone compounds, neuroleptics, psychostiumlants, succinimides and oxazolidinediones, tranquillizers X42 Accidental poisioning by and exposure to narcotics and hallucingoens: Cannabis (derivatives), cocaine, codeine, heroin, lysergide (LSD), mescaline, methadone, morphine, opium (alkaloids) X43 Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other drugs acting on the autonomic nervous system X44 Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified drugs, medicaments, and biological substances X45 Accidental poisoning by and exposure to alcohol X46 Accidental poisoning by and exposure to organic solvents and halogenated hydrocarbons and their vapours X47 Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other gases and vapors X48 Accidental poisoning by and exposure to pesticides X49 Accidental poisoning by and exposure to other and unspecified chemicals and noxious substances 21 Table 3. Drug Overdose Fatalities, 2007-2011 by Cause of Death Cause Number of Deaths Allegheny City of County Pittsburgh Remainder Median Age at Death (years) Allegheny City of County Pittsburgh Remainder Proportion of Drug Deaths* (%) Allegheny City of County Pittsburgh Remainder X40 X41 X42 X43 X44 X45 X46 X47 X48 X49 6 26 487 0 455 47 1 31 0 2 3 5 160 0 141 18 1 7 0 0 3 21 327 0 314 29 0 24 0 2 49.0 45.9 37.7 45.0 46.9 49.5** 65.3 44.5 46.7 46.2 45.5 39.6 45.0 49.5** 75.7 - 52.5 45.8 36.8 45.1 48.3 65.0 47.0** 0.57 2.46 46.16 0.00 43.13 4.45 0.09 2.94 0.00 0.19 0.90 1.49 47.76 0.00 42.09 5.37 0.30 2.09 0.00 0.00 0.42 2.92 45.42 0.00 43.61 4.03 0.00 3.33 0.00 0.28 Total 1055 335 720 39.2 45.3 38.8 100.00 100.00 100.00 *Proportion of drug deaths was calculated by dividing the crude number of fatalities for a particular cause by the total number of deaths for that location **Median age based on average age group in n<2 22 4.0 DISCUSSION Overall, from 2007 to 2011, Allegheny County had fatalities due to accidental poisonings at higher rates than peer counties and at higher rate than the United States. Fatality rates for accidental poisonings were highest in males and whites. The calculated average ages at death points to the largest problem for overdose fatalities being in middle-aged individuals. The death certificates reviewed for this report indicate that there is a drug problem within Allegheny County that is increasing in the suburban and rural areas of the county. There are several different aspects that should be examined and evaluated in order to combat this issue. This includes evaluation of prescribing tendencies of Allegheny County physicians, current medication laws and policies, examining reasons for changes in types of drug fatalities, and consideration of future implications of prescription drug monitoring and intervention programs. Nationwide, there has been a large increase in prescriptions for opioids between the years 1999 to 2010. One reason for this uptick in prescribing has been due to a greater emphasis on treating pain in the medical community.16, 17 There has also been an increase in industry- sponsored advertising, which has included instances of educational brochures suggesting that physicians should ignore signs of opioid dependence in low-risk patients.18 In addition to a change in attitude and industry intervention, long-term opioid use has been shown to lead to tolerance. A solution to tolerance in a patient with chronic pain is to increase opioid dose; however, there is little known about a maximum safe dose of opioids. It has been shown that 23 there is a linear relationship between dose and likelihood of death, with increasing dosages resulting in an increased chance of overdose fatality.19 An increase in poisoning fatalities in the United States has increased at the same rate and magnitude as the increase in prescribing of opioids, which suggests that the primary driving force of fatalities comes from prescription drugs. Within Allegheny County, males have the highest rate of fatalities. This was represented in analysis of the county death records and was shown when the City of Pittsburgh and the Reminder of the County were separated. Although whites had slightly higher rates than blacks for each individual year, average rates of fatalities for blacks and whites were similar for Allegheny County. This trend was not observed in the other areas analyzed. However, it should be noted that when looking at only the City of Pittsburgh, whites had fatality rates from poisoning fatalities higher than their black counterparts. When looking at age at death, the median age for poisonings in the county was 39.2 years. This indicates that the population most at risk for drug overdose fatalities is middle-age individuals. Lastly, the data analyzed shows that, on average, the City of Pittsburgh has higher fatality rates than Allegheny County (as a whole) and higher rates than the Remainder of the County. The trends of fatalities for Allegheny County are consistent with the SAMHSA findings of substance abuse and dependence for the United States.7 This suggests that drug abuse and dependence lead to future poisoning fatalities. It was found that for 2007 to 2011, Allegheny County had higher fatality rates than peer counties in Detroit, Michigan and Chicago, Illinois. One reason for this difference could be the result of the structure of Allegheny County in comparison to the more urbanized Wayne and Cook counties. Research has shown that counties with rural areas tend to have higher prescription drug overdose fatalities in comparison to entirely urban and suburban counties.10, 11 24 Another possible explanation for these dissimilar rates is that these counties come from states with differing laws. Wayne County follows Michigan law, which was established in 1988 to monitor drug schedules II through V (see Appendix), Michigan has the strictest laws of these states examined in this report and may explain why Wayne County has the second lowest drug fatality rates of the peer counties examined.20 Since 1961, Cook County (Illinois) has monitored scheduled II drugs and has the lowest peer county rate.21 Pennsylvania has the newest laws; with schedule II drugs being monitored as of 2002 and new policy—passed in the fall of 2014—that will require monitoring of schedules III through V.20,22 Philadelphia and Allegheny County, both in Pennsylvania, had the highest rates in all subgroups, which could be a result of having newer drug monitoring laws than other states. States not only hold the power to regulate the use and prescribing tendencies of opioid pain relievers, but also are responsible for financing and regulating health care for Medicaid populations—who are at a greater risk for overdose.5 Therefore, it is important that states take responsibility for decreasing risk of overdose within their jurisdiction. Recent evidence has shown that the types of drug use associated with fatalities have changed over time. A study by Paulozzi and colleagues showed that prescription drugs have replaced heroine and cocaine as the leading causes of drug fatalities. This article also comments that drug overdoses are no longer an “urban problem”.11 Although the data for years 2007 to 2011 does not show that Allegheny County has experienced a complete shift of drug fatalities from the City of Pittsburgh (urban) to the Remainder of the County (suburban and rural), there has been a recent increase in drug fatalities in the suburban and rural portions of the county that was not seen in previous years. It should also be noted that Allegheny County had higher fatality rates due to accidental poisonings than counties that contain large metropolitan areas such as 25 Chicago and Detroit. This indicates that a shift in where and by whom drugs are being used is happening. A nationwide shift of drug use from large cities to smaller cities and non-metropolitan areas, such as Allegheny County poses several problems. The first being that increased drug use in a population has been shown to lead to an increase in other types of injury. This is because drug abuse is a risk factor for both suicide and motor vehicle crashes, which are already more common in rural areas.24, 25, 26 Another issue with drug use expanding out of urban populations is that physicians in suburban and rural areas are not always accustomed to treating pain and may be targeted by drug manufacturers, as discussed earlier.24, 27, 28 This report utilized standardized data programs and data collection, which conferred several strengths and introduced some limitations. Death certificate data has conflicting views of it’s quality as a data source due to errors in completing the certificates and missing information.29 Although errors within the certificates the Allegheny County Vital Statistics data set inevitably exists, it should be noted that the strengths of this data collection method outweigh the possible flaws. One such strength is that all deceased Allegheny County residents have a death certificate that is submitted to the Allegheny County Health Department, making this sample nearly perfect. Another strength is that the deaths examined were due to accidental causes, which means that a coroner reviewed the deaths and completed the death certificate. Because the deaths are accidental, the majority of the sample received toxicology to determine the particular cause of death; thus leading to potentially more accurate data than typical death certificates. Another possible source of limitations comes from age-adjustment. Since age-adjustment relies on rates, it can be affected by population size; however, age-adjustment is a necessary step for comparison 26 and allowed for accurate evaluation of the differences in drug fatalities between Allegheny County and peer counties with different age structures. This report has indicated that Allegheny County has a drug-poisoning problem that warrants further evaluation and intervention. An implication of these results is that Allegheny County needs to utilize drug-monitoring programs in order to provide targeted interventions for populations at highest risk for drug fatalities. Based on the records reviewed, middle-aged men living in the City of Pittsburgh are at highest risk for death from a drug overdose. With this being said, it is important that the female and suburban/rural populations be monitored due to the emerging trend of abuse for these populations. A drug-monitoring program, such as the one passed by Pennsylvania state representatives in September 2014 under Senate Bill 1180, will allow for public health professionals to determine where misuse and abuse is happening and by what population subgroups. Other types of data that should be monitored include Naloxone administration, hospital admissions relating to drug use, and arrest data. By monitoring different types of drug use data, public health officials will be able to understand what populations are using drugs and which populations are dying from overdose. Because populations who are abusing drugs are changing, it is important that prevention efforts shift accordingly in order to focus on populations that were not previously considered at high risk.11 By knowing to whom and where the problem exists, targeted interventions in Allegheny County can be created. A type of intervention that should be considered by treatment centers in Allegheny County is the use of medication-assisted technologies (MATs). Despite their safe and cost effective ability to reduce risk of overdose, MATs are underutilized. MATs consist of treatments such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone to rehabilitate drug addicts to a life free of addictive substances. MATs have not only been successful in improving patient’s social 27 functioning, but have also been shown to reduce risks of infectious disease transmission and engagement in criminal activities.30, 31 Currently, this type of treatment is not heavily utilized; less than half of private-sector treatment programs adopt this practice and of those that do, only 34.4% of patients receive them.28 Likely reasons as to why MATs are not relied upon are that there are provider skepticism, inadequate doses which result in relapse, and limitations due to policy and regulation. Such regulations are placed by insurance providers and limit the amount of dosages, provide minimal counseling, and have strict authorization requirements that impede their use.31, 32 If Allegheny County wishes to see lower rates of drug fatalities, it must consider interventions based on the intervention’s success and cost-effectiveness and work to overcome barriers to such treatments. Although a prescription drug-monitoring bill is an important step for Pennsylvania to decrease its rate of drug fatalities, it is only the first step in a series of necessary policy and attitude changes for the state. Another important change to legislation comes from the amendments to Senate Bill 1164, which has been coined the “Good Samaritan Law”. This bill allows for Good Samaritan immunity from prosecution for certain drug crimes to individuals who are seeking help for a companion who overdoses on drugs. This bill will also allow for the expansion of naloxone—an opioid antagonist—to individuals who have a risk of overdosing and their friends and family members.23 This bill not only helps to overcome the problem of drug overdose fatalities occurring due to fear of seeking medical attention because of potential legal problems, but also allows for the widespread use of Naloxone in instances of drug overdose. In the years 1996 to 2010, Overdose Education trained 50,000 potential bystanders with Naloxone Distribution (OEND) programs in the United States. This program resulted in the reversal of over 10,000 opioid overdoses.33 Likewise, simulations have shown that Naloxone distribution to 28 known heroin abusers increases quality of life years and is a cost-effective way to decrease death from drug abuse.34 Even though the bill has been passed and Naloxone has shown to be an effective life-saving tool, there are still many barriers to its practical use. Pushback of Naloxone distribution programs include questions on whether lay responders will be able to use the opioid antagonist effectively, misconceptions that Naloxone will increase opioid use and promote a “false safety” among drug users, and that it will reduce interaction with hospital emergency departments.35 It is important that education programs within Allegheny County follow the passing of this bill in order to communicate that there is currently no significant evidence that untrained rescuers are any different than trained rescuers in regards to management of overdose events. In addition to this, there is no evidence that opioid use increases after Naloxone administration. Under the specifications of the bill, it is required that those who use Naloxone are transported immediately to a medical facility for further observation.23,35 Lastly, the study of OEND participants found that educating family and friends about overdose through Naloxone education was viewed as having more value and was more acceptable than discussing how to reduce drug use behaviors—which could potentially lead to a future decrease in drug use.36 Allegheny County is currently in a state of high demand for education and intervention programs for drug abuse. Based on data from 2007 to 2011 on specific cause of death, the biggest contributor to drug fatalities are from narcotic and hallucinogen use and abuse. Current legislative amendments offer the potential for promising change within the state, but must be followed with further monitoring and education programs. Likewise, future continuous monitoring of drug overdose fatalities by public health institutions such as the Allegheny County Health Department and the University of Pittsburgh will allow for targeted interventions for high 29 risk and emerging risk populations in order to reduce drug use and poisoning fatalities within Allegheny County. This report provided a necessary first step in addressing the problem of drug abuse in Allegheny County. Comparison to similar counties across the United States showed that, despite its similarity to other urban areas, Allegheny County has a problem with drug use that exceeds the nation and its peers. Combatting these trends in drug abuse in Allegheny County needs to be a major public health priority. 30 APPENDIX: TECHNICAL NOTES Definition of Key Terms DRUG OVERDOSE: Ingestion or application of a drug or other substance in quantities that was greater than recommended or prescribed. This event may result in a toxic state or death. FATALITY: Unexpected death CAUSE OF DEATH: The causal agents or underlying causes that result in death. Underlying causes are any diseases, injuries, or accidents, which eventually lead to death. The International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), codes causes of death or underlying causes. See Table 2. MEDIAN AGE AT DEATH: An indicator of premature mortality. Is the exact midpoint of ages of deaths that occurred in a designated time period. RACE: Bridged population estimates for Allegheny County are used to calculate the rates from 2007 and 2008. These estimates are used from bridging the 31 race categories used in the 2000 census as directed in the 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards for the collection of data on race and ethnicity. 31 Drug Schedules37 According to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration: Schedule I: Defined as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. This classification is used for the most dangerous drugs of all the drug schedules with potentially severe psychological or physical dependence. o Examples: heroin, LSD, marijuana, ecstasy, methaqualone, and peyote Schedule II: Substances or chemicals that have a high potential for abuse, but less abuse potential than Schedule I drugs. Use of Schedule II drugs can potentially lead to severe psychological or physical dependence. o Examples: cocaine, methamphetamine, methadone, Demerol, OxyContin, fentanyl, Adderall, and Ritalin Schedule III: Drugs with moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence. Abuse potential is less than Schedule I and Schedule II drugs, but more addictive than Schedule IV drugs. o Examples: Vicodin, Tylenol with codeine, anabolic steroids, testosterone Schedule IV: Substances or chemicals that have a low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence o Examples: Xanax, Soma, Darvon, Darvocet, Valium, Ativan, Talwin, Ambien Schedule V: Defined as substances with the lowest potential for abuse of the Scheduled drugs and consist of preparations containing limited quantities of certain narcotics. 32 o Examples: Robitussin AC, Lomotil, Motofen, Lyrica, Parepectolin Formulas for Rates AGE ADJUSTED MORTALITY RATE = Age-specific mortality rate multiplied by the weight for that age group in the standard population Age adjusting allows for control over any differences that may exist in the underlying age structures of different populations. Ageadjusted death rates cannot be compared to crude rates and cannot be interpreted as an absolute measure of mortality. All ageadjusted rates used in this essay are adjusted using the direct method with the U.S 2000 Standard Million Population. Allegheny County Census Tracts For this report, an Allegheny County Census tract less than or equal to 40000 were considered “City of Pittsburgh” and a tract greater than 4000 but less than 80000 were considered “Remainder of the County”. 33 BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. National Drug Intelligence Center. (2001). United States-Canada Border Drug Threat Assessment. Report No. 2002-R0423-001. Johnstown, PA. 2. Jones, C. M., Mack, K. A., & Paulozzi, L. J. (2013). Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA, 309(7), 657–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.272 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Primary care and public health initiative: balancing pain management and prescription opioid abuse: educational module. http://www.cdc.gov/primarycare/materials/opoidabuse/. Published October 24, 2012. 4. Addressing prescription drug abuse in the United States: current activities and future opportunities. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Home and Recreational Safety. Retrieved October 30, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/overdose/facts.html 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids among Medicaid enrollees - Washington, 2004-2007. (2009). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 58(42), 1171–5. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19875978 6. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2014). The Science of Drug Abuse & Addiction. Retrieved September 20, 2014, from http://www.drugabuse.gov/ 7. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. 8. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers and other drugs among women-United States, 1999-2010. (2013). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(26), 537–42. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23820967 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): National vital statistics reports: deaths: final data for 2009. National Vital Statistics Report 2011, 60(3):81–82. 34 10. Hall, A. J., Logan, J. E., Toblin, R. L., Kaplan, J. A., Kraner, J. C., Bixler, D., Crosby, A., Paulozzi, L. J. (2008). Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA, 300(22), 2613–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2008.802 11. Paulozzi, L. J., & Xi, Y. (2008). Recent changes in drug poisoning mortality in the United States by urban-rural status and by drug type. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 17(10), 997–1005. doi:10.1002/pds.1626 12. Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2012). Persons Arrested. Retrieved October 30, 2014, from http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2012/crime-in-the-u.s.-2012/personsarrested/persons-arrested 13. U.S. Department of Justice. (1994). Fact Sheet: Drug-Related Crime. NCJ-149286. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/DRRC.PDF 14. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Highlights of the 2009 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) findings on drug- related emergency department visits. The DAWN Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010. Available at http://oas. samhsa.gov/2k10/dawn034/edhighlights.htm 15. ICD-10 : International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. Print. 16. Van Zee, A. (2009). The promotion and marketing of OxyContin: commercial triumph, public health tragedy. American Journal of Public Health, 99(2), 221–7. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.131714 17. The use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain. A consensus statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society. (1997). The Clinical Journal of Pain, 13(1), 6–8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9084947 18. Stanos SP, M. G. (2012). Appropriate Use of Opioids in Chronic Pain: Caring for Patients and Reducing Risks. Englewood, CO. 19. Dowell, D., Kunins, H. V, & Farley, T. a. (2013). Opioid analgesics--risky drugs, not risky patients. Jama, 309(21), 2219–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.5794 20. National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. (2006b). Michigan’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP). Retrieved from http://www.namsdl.org/library/2BBB4C5965BE-F4BB-A41D0E849476B7FF/ 21. National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. (2006a). Illinois’ Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP). Retrieved from http://www.namsdl.org/library/2B9E7FA81372-636C-DD2E9959BB3C9BFE/ 35 22. National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. (2006c). Pennsylvania’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP). Retrieved from http://www.namsdl.org/library/2C1AAA081372-636C-DD16A12271F62285/ 23. Providing for prescription drug monitoring; creating the ABC-MAP Board; establishing the Achieving Better Care by Monitoring All Prescriptions Program; and providing for unlawful acts and penalties, PA S.1180, Act No. 191 (2014). 24. Eberhardt MS, Ingram DD, Makuc DM, et al. (2001). Urban and Rural Health Charbook, Health, United States, 2001. Hyattsville, MD. 25. Rivara, F. P., Mueller, B. A., Somes, G., Mendoza, C. T., Rushforth, N. B., & Kellermann, A. L. (1997). Alcohol and illicit drug abuse and the risk of violent death in the home. JAMA, 278(7), 569–75. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9268278 26. Walsh, J. M., de Gier, J. J., Christopherson, A. S., & Verstraete, A. G. (2004). Drugs and driving. Traffic Injury Prevention, 5(3), 241–53. doi:10.1080/15389580490465292 27. Breuer, B., Pappagallo, M., Tai, J. Y., & Portenoy, R. K. (2007). U.S. board-certified pain physician practices: uniformity and census data of their locations. The Journal of Pain : Official Journal of the American Pain Society, 8(3), 244–50. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2006.08.009 28. United States General Accounting Office. (2003). OxyContin Abuse and Diversion and Efforts to Address the Problem. Report No. GAO-04-110. Washington, DC. 29. Glasser, J. H. (1981). The quality and utility of death certificate data. American Journal of Public Health, 71(3), 231–3. Retrieved from http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1619790&tool=pmcentrez&ren dertype=abstract 30. Schwartz, R. P., Gryczynski, J., O’Grady, K. E., Sharfstein, J. M., Warren, G., Olsen, Y., Mitchell S.G., Jaffe, J. H. (2013). Opioid agonist treatments and heroin overdose deaths in Baltimore, Maryland, 1995-2009. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 917–22. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301049 31. Knudsen, H. K., Abraham, A. J., & Roman, P. M. (2011). Adoption and implementation of medications in addiction treatment programs. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 5(1), 21–7. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d41ddb 32. Clark, R. E., & Baxter, J. D. (2013). Responses of state Medicaid programs to buprenorphine diversion: doing more harm than good? JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(17), 1571–2. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9059 36 33. Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone - United States, 2010. (2012). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(6), 101–5. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22337174 34. Coffin, P. O., & Sullivan, S. D. (2013). Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal in Russian cities. Journal of Medical Economics, 16(8), 1051–60. doi:10.3111/13696998.2013.811080 35. Doe-Simkins, M., Quinn, E., Xuan, Z., Sorensen-Alawad, A., Hackman, H., Ozonoff, A., & Walley, A. Y. (2014). Overdose rescues by trained and untrained participants and change in opioid use among substance-using participants in overdose education and naloxone distribution programs: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 297. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-297 36. Sherman, S. G., Gann, D. S., Tobin, K. E., Latkin, C. A., Welsh, C., & Bielenson, P. (2009). “The life they save may be mine”: diffusion of overdose prevention information from a city sponsored programme. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 20(2), 137–42. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.02.004 37. United States Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). Drug Scheduling. Retrieved October 1, 2014, from http://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml 37